Joshua's Altar on Mt. Ebal

Deuteronomy 27:5; Joshua 8:30

AD 2019 Mt. Ebal Curse Tablet: “Defixio”

Monograph by Steven Rudd on AD 2019 Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet

"'You shall make an altar

of earth for Me, and you shall sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and

your peace offerings,

your sheep and your oxen; in every place where I cause My name to be

remembered, I will come to you and bless you.(Exodus 20:24)

'If you make an altar of stone for Me, you shall

not build it of cut stones, for if you wield

your tool on it, you will profane it.

'And you shall not go up by steps to My altar,

so that your nakedness will not be exposed on it.' " (Exodus 20:25-26)

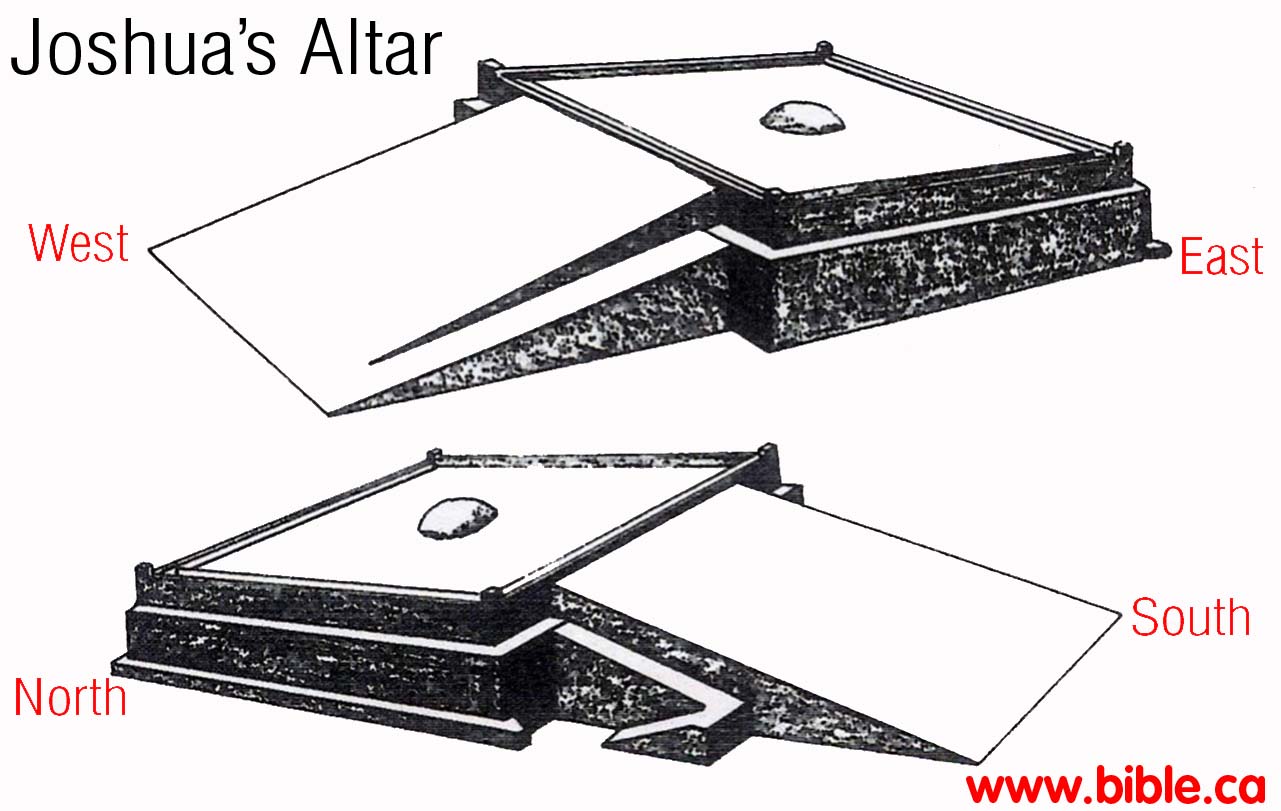

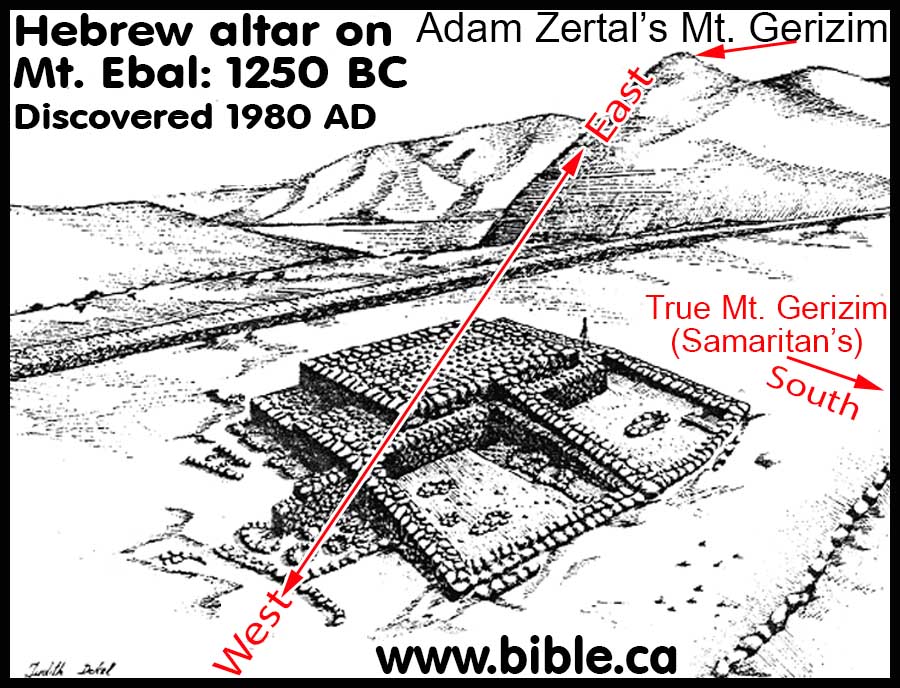

Altar of Joshua, Mt. Ebal

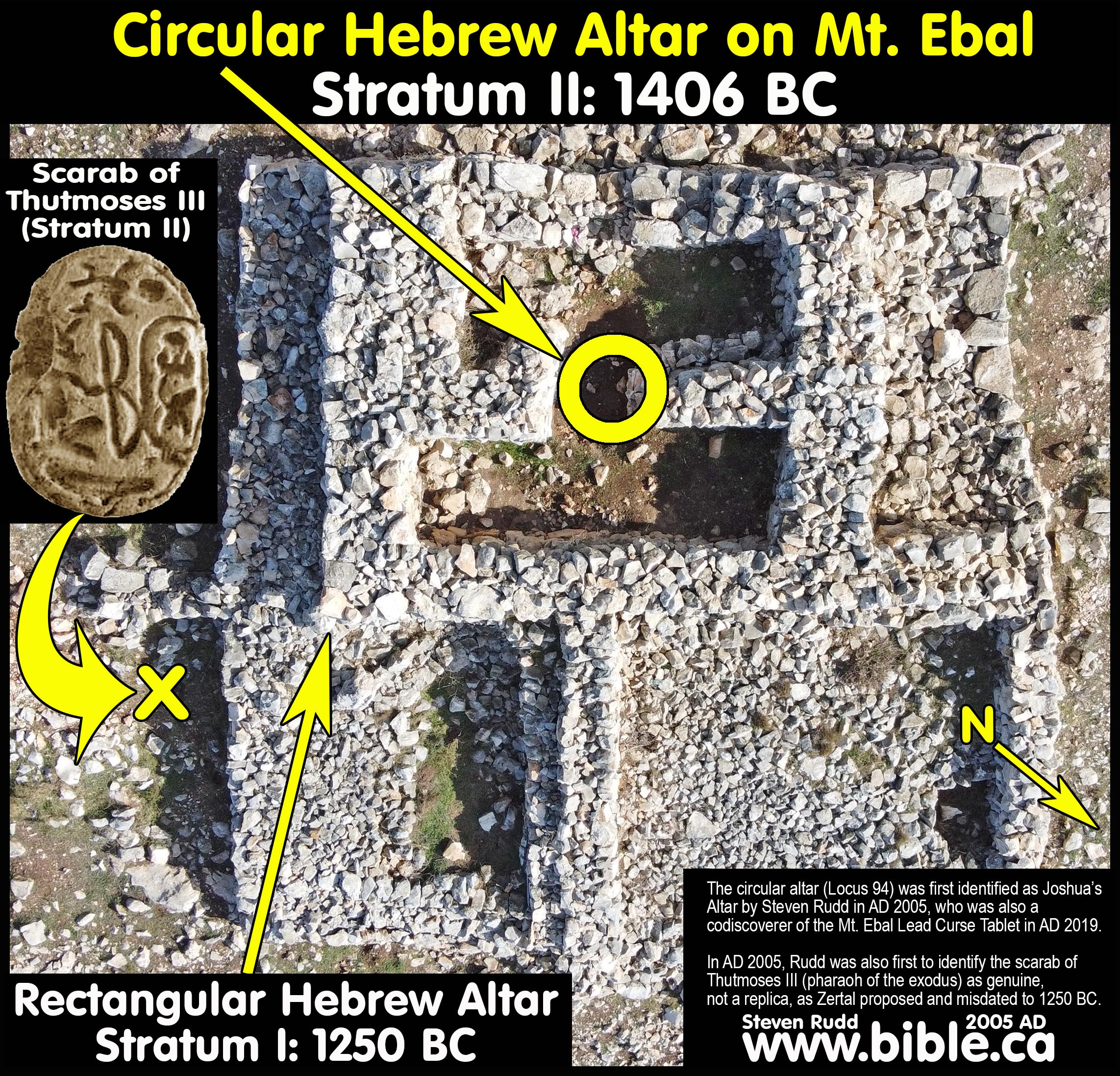

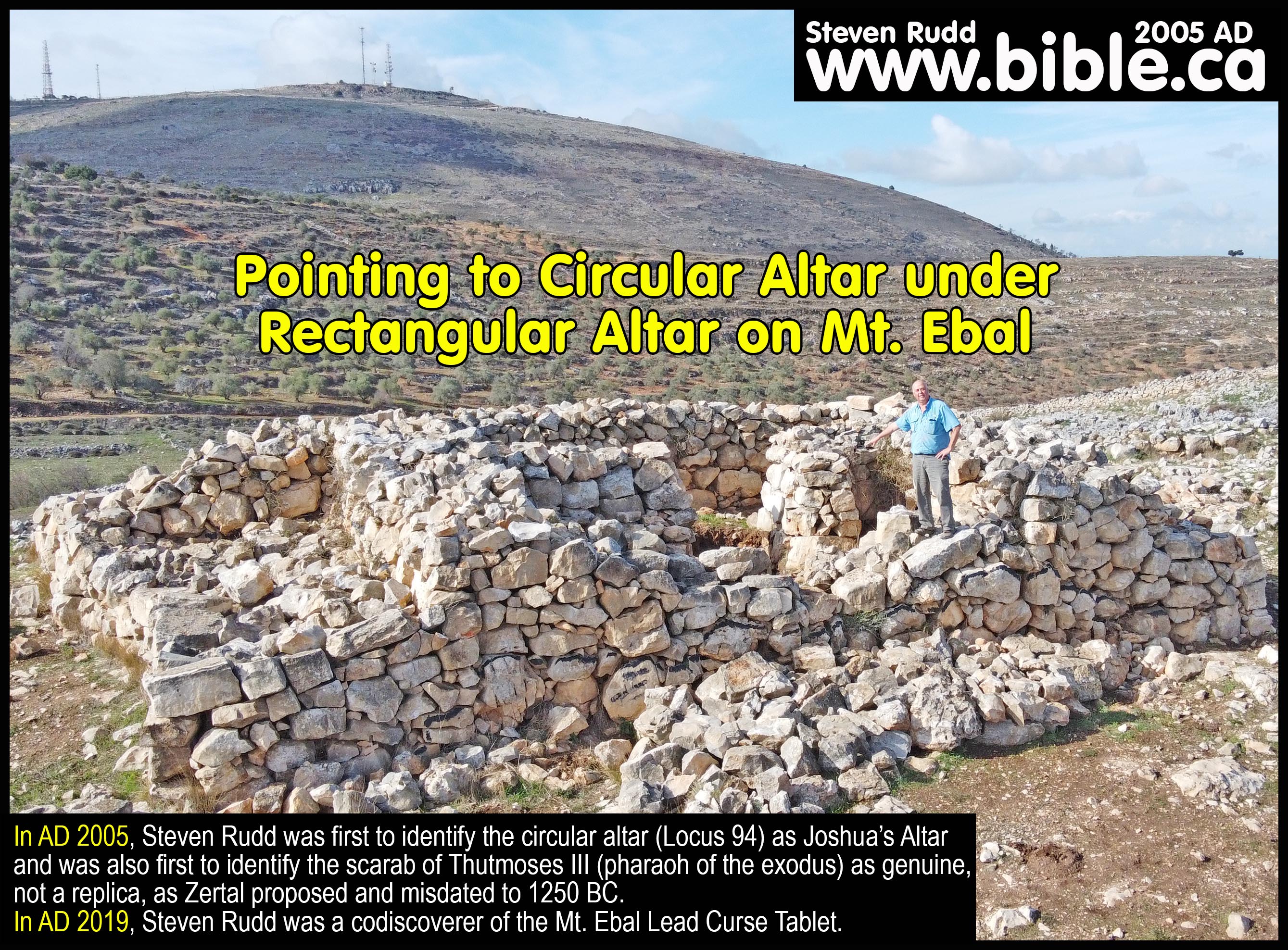

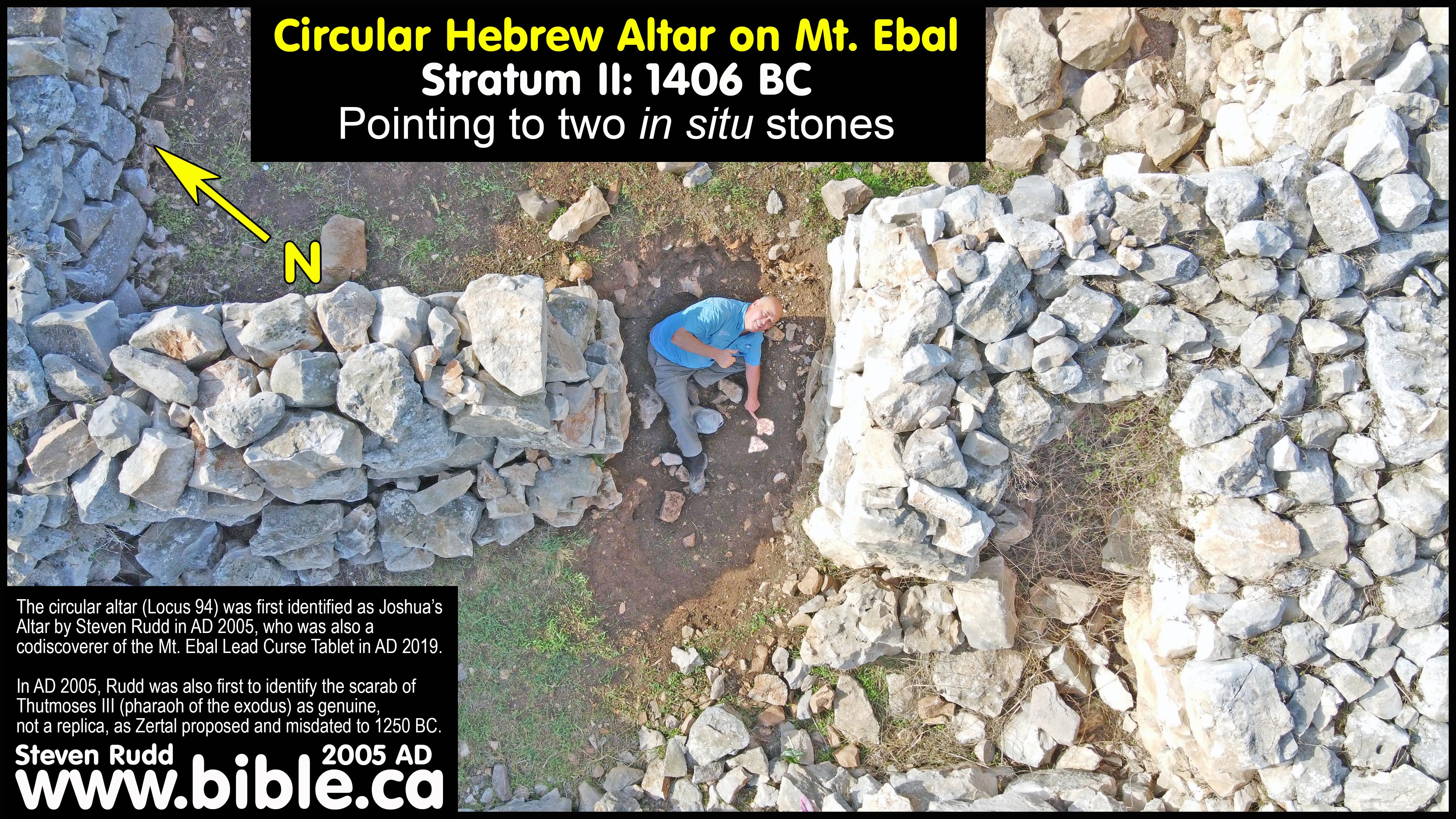

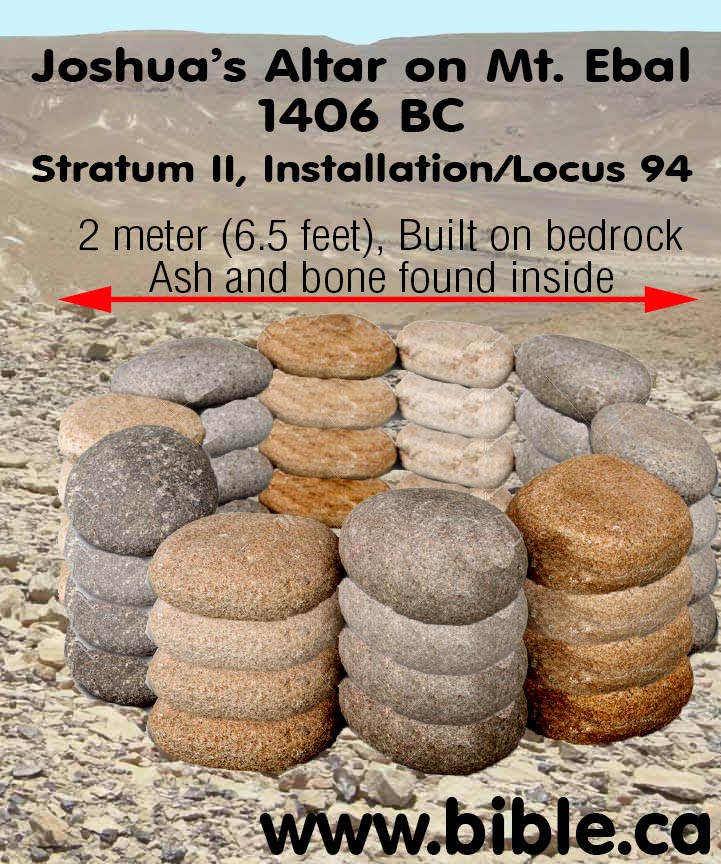

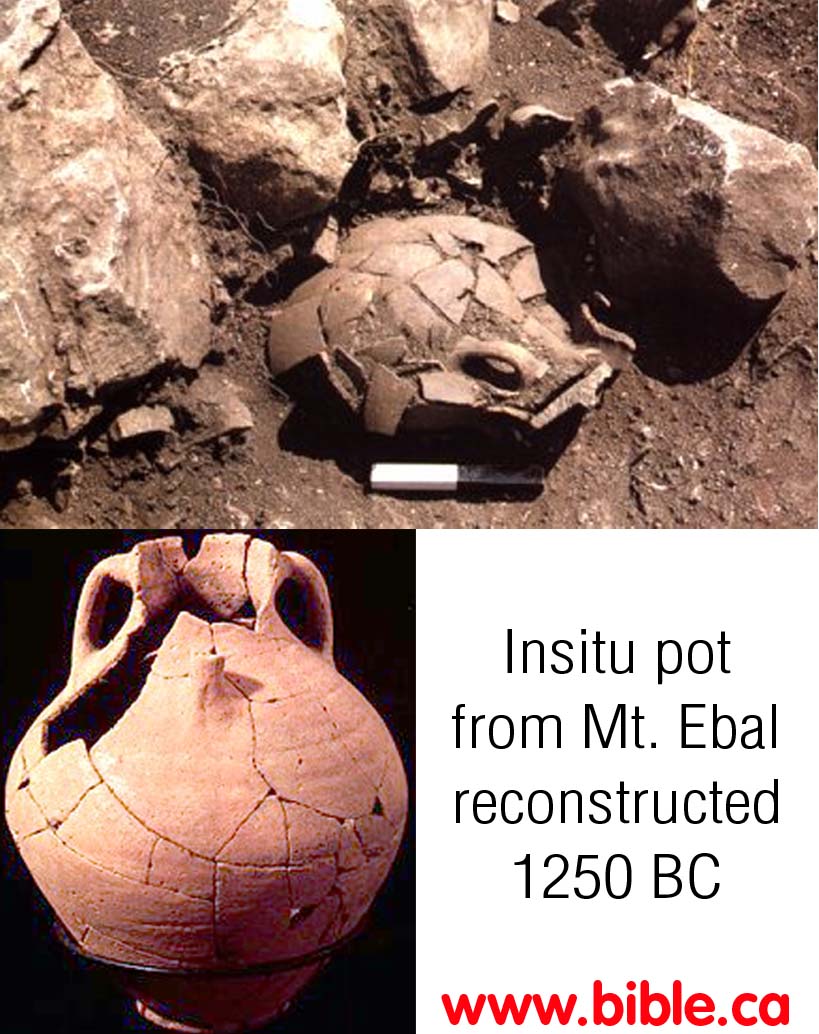

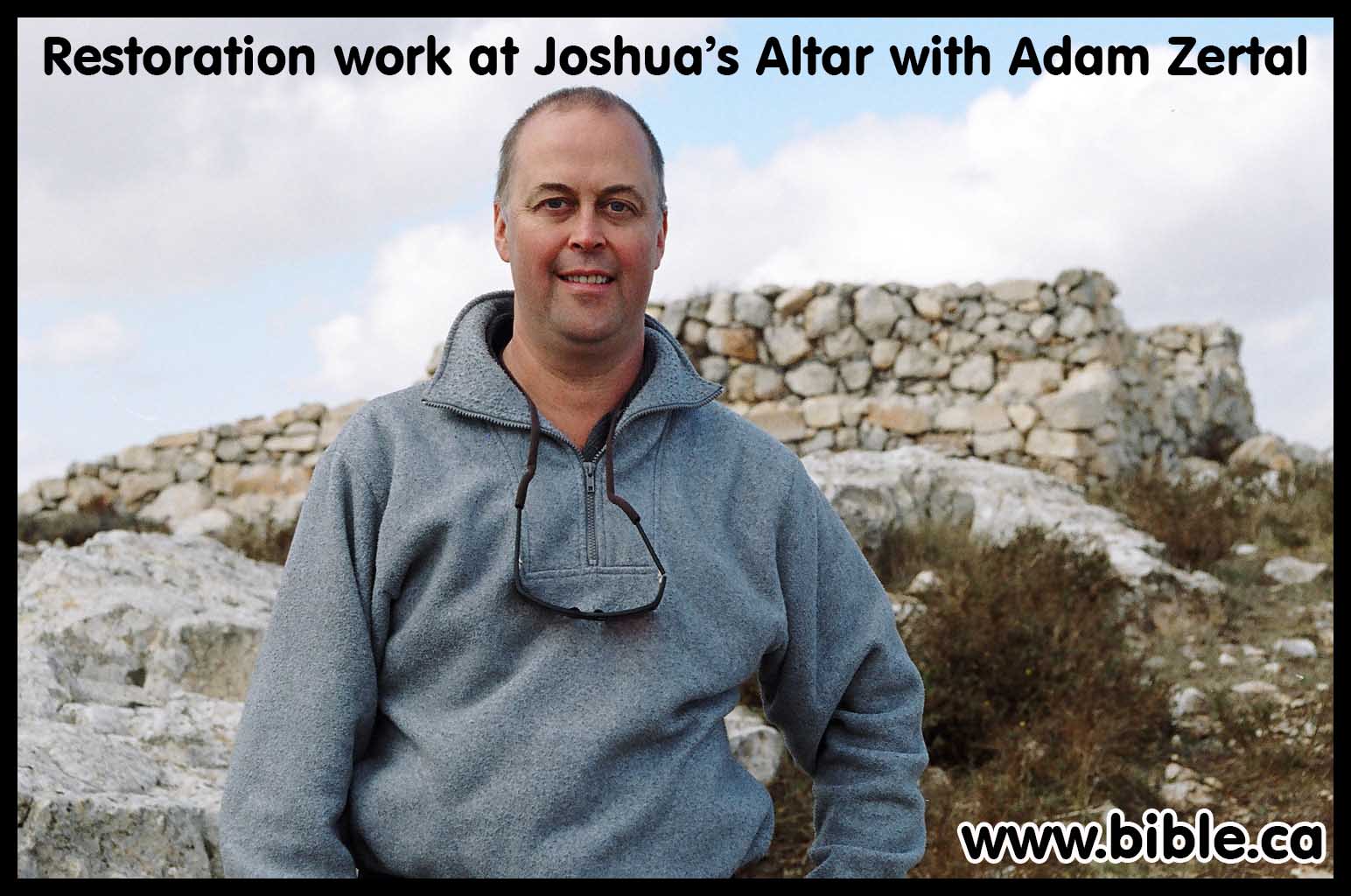

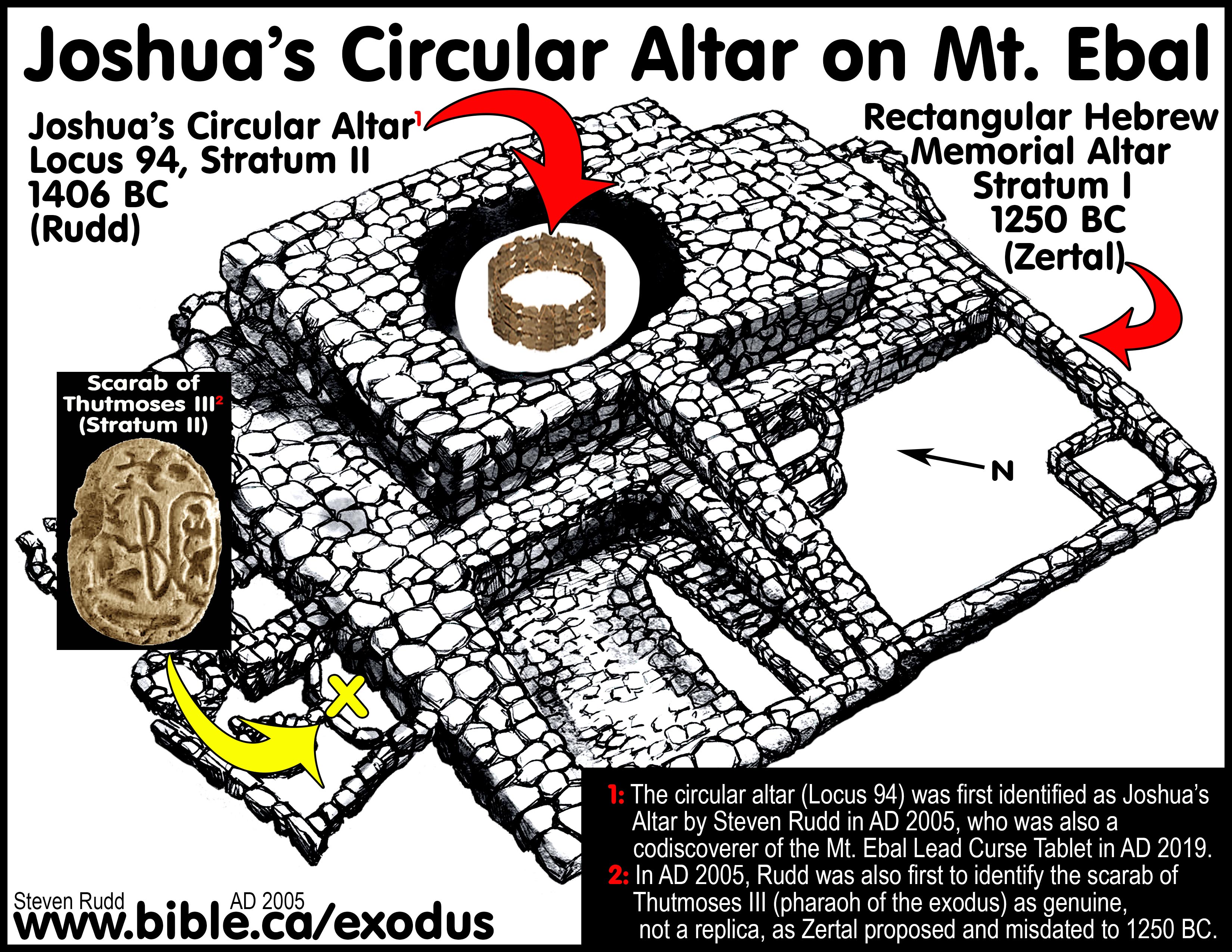

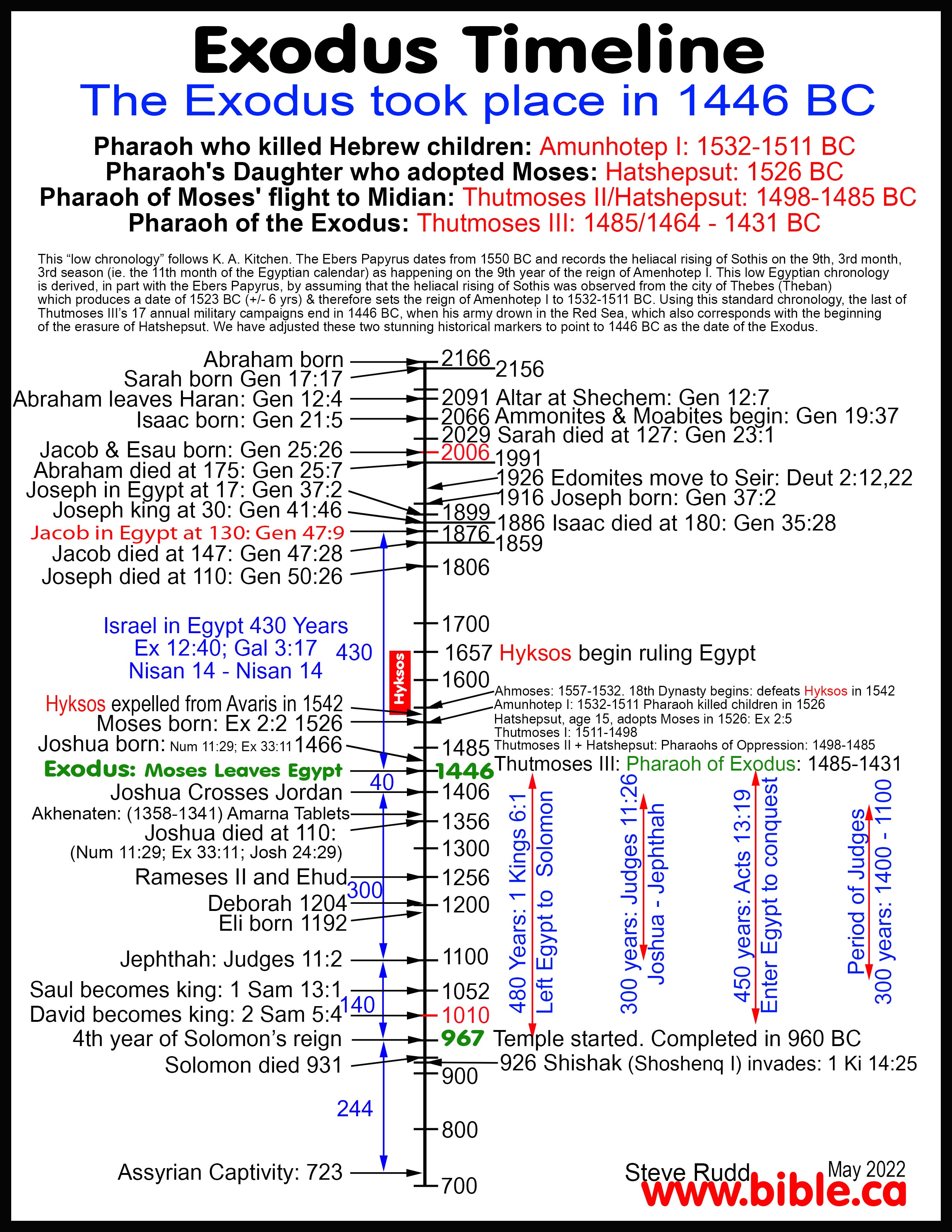

1. In November AD 2004, Steven Rudd conducted restoration work under the direct supervision of Adam Zertal on Joshua’s Altar at Mt. Ebal. Zertal identified two strata in his 1985 excavation reports. Zertal considered the rectangular alter (Stratum I) to be Joshua’s altar which he dated to about 1250 BC at the time of Rameses II. Zertal dated the circular altar (Locus 94, Stratum II) under the rectangular to around 1300-1275 BC. Till his death, Zertal always identified Joshua’s altar as the rectangular structure and never believed the round circular altar (Locus 94/stratum II) was built by Joshua. Zertal believed Joshua built the rectangular alter over top of an older circular alter that predated the rectangular altar by 25-50 years. The elephant in the excavation room apparent to Steven Rudd was that the exodus occurred in 1446 BC under Thutmoses III, not 1250 BC under Ramses II as Zertal believed. This meant that it was impossible for the rectangular altar to be built by Joshua.

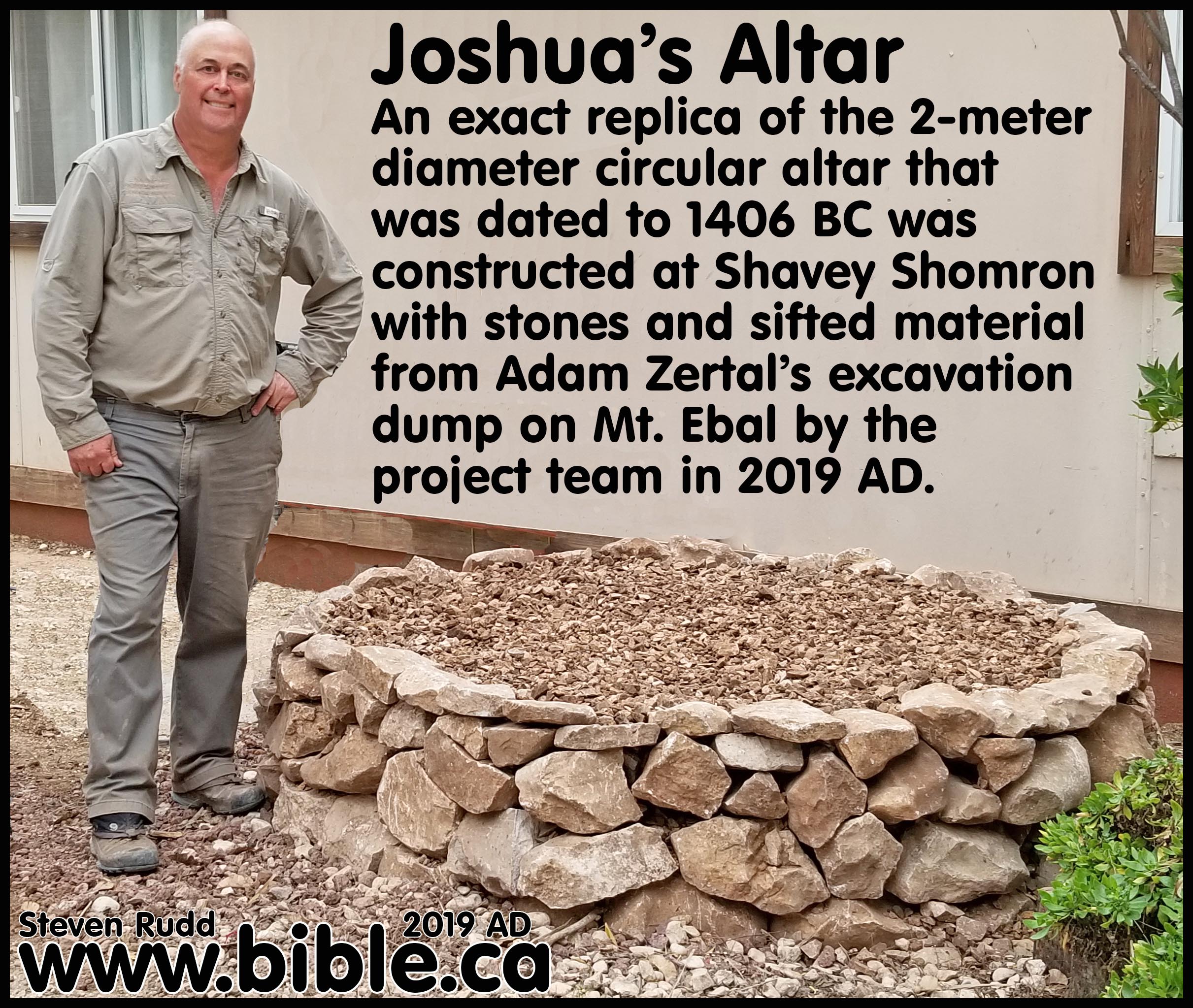

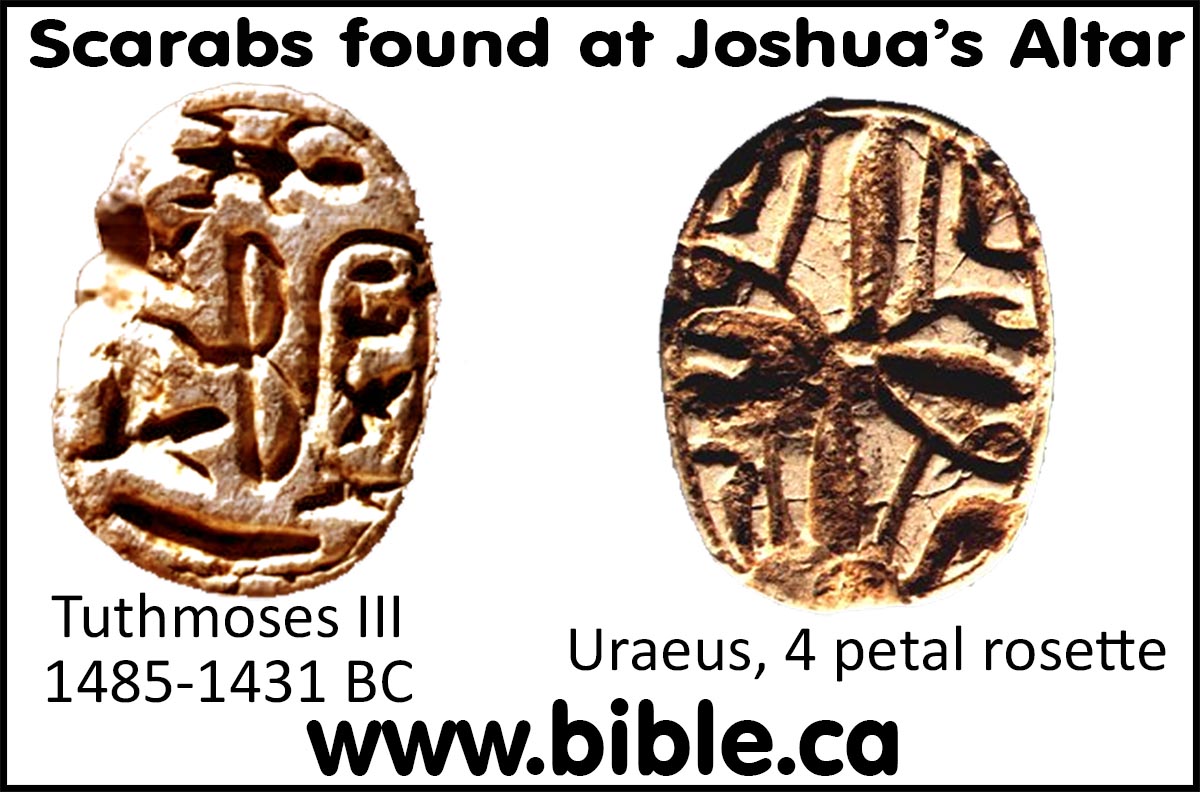

2. In AD 2005, Steven Rudd studied Zertal’s excavation reports, and was the first one to redate the circular alter to 1406 BC and identify it as Joshua’s altar, not the rectangular structure above. This was based upon Biblical chronology and the Thutmoses III scarab Zertal excavated. Rudd rejected (in 2005 AD) Zertal’s claim that the Thutmoses III scarab was a replica created at the time of Ramses II. All these details were published by Rudd in AD 2005 on the webpage, www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-altar-of-joshua.htm, which has enjoyed a first hit “Google” search result for “Joshua’s Altar” since AD 2005. During this time, it was the most read monograph on Joshua’s altar in the world, as it true today. Gradually, many came to agree with Rudd’s conclusion that the round altar (Locus 94, Stratum II) was Joshua’s altar that dated to 1406 BC.

3. Steven Rudd’s personal plea to Zertal in 2005:

a. “We would humbly invite Adam Zertal to read this paper on the Exodus being at 1446 BC, not 1250 BC. The altar changed him from a Bible skeptic to a Bible believer. We suggest that he go all the way and accept the Bible's date of 1406 BC when Joshua built his altar. Zertal probably knows enough about the site that he could actually make a good case for this round ring of rocks being dated to 1406 BC, but simply could not because he mistakenly believed the exodus happened in 1250 BC. If he accepts the Bible's date of the exodus of 1446, then he can date the 6.5 foot diameter circle of stones up to 150 years earlier and still be within the time Israel crossed the Jordan. He can contact the author (Steven Rudd) by email here if he wishes further discussion.”

AD 2022: Multi-spectral scanning project of plaster excavated by Adam Zertal:

1. Scripture said Joshua’s altar was plastered, and the ten commandments were written thereon. In AD 1985 Adam Zertal discovered plaster (currently at University of Haifa) which may be scanned with the optical ostraca detector invented by Steven Rudd used on site at the Shiloh excavation since AD 2018 (see photo below). This scientific imaging machine allows archaeologists to see if any writing is visible under UV and Infrared light.

Lead Curse Tablet from Mt. Ebal

Monograph by Steven Rudd on AD 2019 Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet

1. The M.E.D.S. (Mount Ebal Dump Salvage) team spent two weeks at Mt. Ebal in December 2019 to January 2020 and at the Shavey Shomron kubutz in Israel west of Nablus. Steven Rudd was a staff member of the M.E.D.S. excavation team who designed and built the dry and wet sifting machines to reexamine Adam Zertal’s 1980’s excavation dump piles at Joshua’s Altar on Mt Ebal. Although all members participated in all aspect of the excavation, it was Frankie Snyder who discovered the Lead Curse Tablet in the wet sifting machine. It would turn out to be one of the most important archaeological finds in 100 years because it was the oldest Hebrew text ever discovered, and the oldest reference to God’s personal name, “YHWH”, which God first revealed to Moses at the burning bush in 1447 BC at the foot of Mt Sinai near Midian in Saudi Arabia. It also confirmed the inspiration of scripture by showing that Mt. Ebal was the mountain of curses in Deut 27. What you read in the book you find in the ground.

2. In 2022, tomographic scans of the 2019 Mt Ebal Curst Tablet were completed by two epigraphers, Pieter Gert Van der Veen of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, and Gershon Galil of the University of Haifa. These scientists employed advanced tomographic scans to recover the hidden text. All the letters on the inside belong to the same physical level, indicating they were part of a script written on a flat strip of lead then folded into a square. Daniel Vavrik and his colleagues from the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech ensured the accuracy of the raw data which the team interpreted. An academic, peer-reviewed monograph of the Lead Curse Table published in AD 2022 was the result of the collaborative efforts of Scott Stripling, Gershon Galil, Ivana Kumpova, Jaroslav Valach, Pieter Gert van der Veen, Daniel Vavrik, and Michal Vopalensky.

|

M.E.D.S. team: 22 Codiscoverers of the Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet, December 2019 Monograph by Steven Rudd on AD 2019 Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet |

|

|

(In alphabetical order) 1. Melody Bogle (Artist) 2. Miki Clouser (Volunteer) 3. Sherrie Dwyer (Volunteer) 4. Jacob Figueroa (Volunteer) 5. Brent French (Volunteer) 6. Emmeline Gerhart (Volunteer) 7. Perry Gerhart (Special Projects Engineer) 8. Greg Gulbrandsen (Wet Sifting Supervisor) 9. Ellen Jackson (Metal Detectorist) 10. Zvi Koenigsberg (Laison) 11. Scott Lanser (ABR Director) 12. Kevin Larsen (Staff) 13. Suzanne Lattimer (Staff) 14. Abigail Leavitt (Asst. Director) 15. Aaron Lipkin (Logistics Coordinator) 16. Mike Luddeni (off site photographer) 17. Jordan McClinton (Volunteer) 18. Steve Rudd (Wet Sifting Engineer) 19. Henry Smith (Administrative Director) 20. Frankie Snyder (Small Finds Specialist) 21. Scott Stripling (Director) 22. Gary Urie (Volunteer) |

|

Introduction:

1. Adam Zertal excavation reports:

a. An Early Iron Age Cultic Site On Mount Ebal: Excavation seasons 1982-1987, Preliminary report by Adam Zertal

b. Has Joshua's Altar Been Found on Mt. Ebal? by Adam Zertal (BAR, Feb 1985)

c. The cult site on mount 'ebal. A stone mound on the northeastern ridge. By Adam Zertal (Nov 2004)

2. Site location: 50 km N of Jerusalem: GPS: 32.239679N 35.287205E

3.

On April 6, 1980, Adam Zertal, Ph.D, Prof. Of

Archeology, Univ. of Haifa was doing a formal archaeological survey of the

traditional lands of Manasseh and discovered a Hebrew Altar that dated to 1250

BC. Using pottery to date the site Zertal said: "More

important, however, is that they [the pottery] fix a date for the construction

of the altar - approximately 1250 B.C.E." (Adam Zertal 2004 AD)

Zertal is the author of "A Nation is Born: The Mt. Ebal Altar and the

Beginnings of the Nation of Israel". See also: (Zertal, A. 1986/87 An

Early Iron Age Cultic Site on Mt. Ebal: Excavation Seasons 1982-1987. Tel Aviv

13-14: 105-65. 1993.) and (The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavation in

the Holy Land, Vol. 1, ed. E. Stern. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and

Carta. Ebal, Mount. Pp. 375-77)

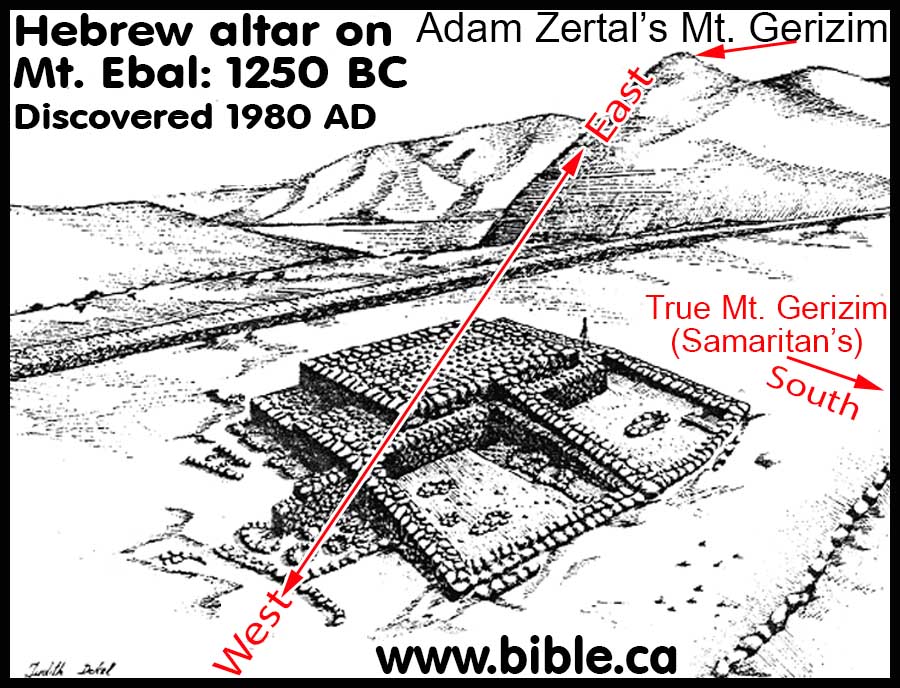

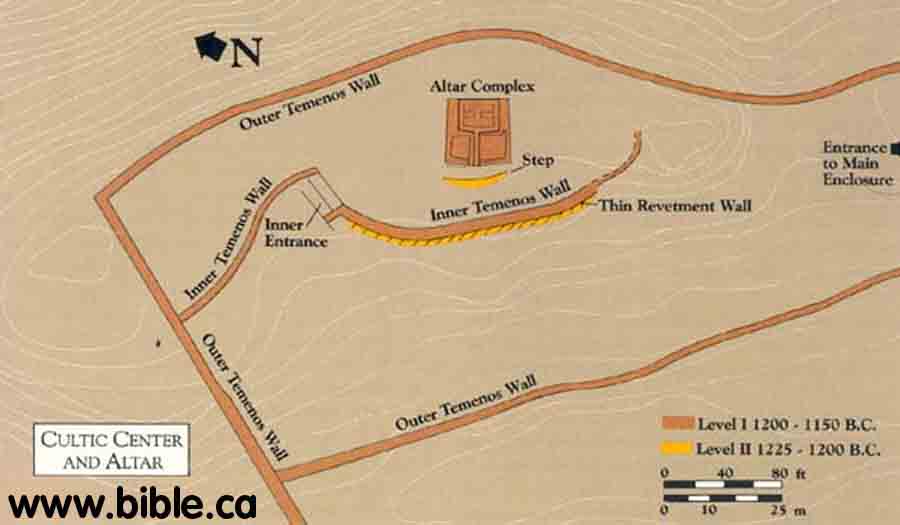

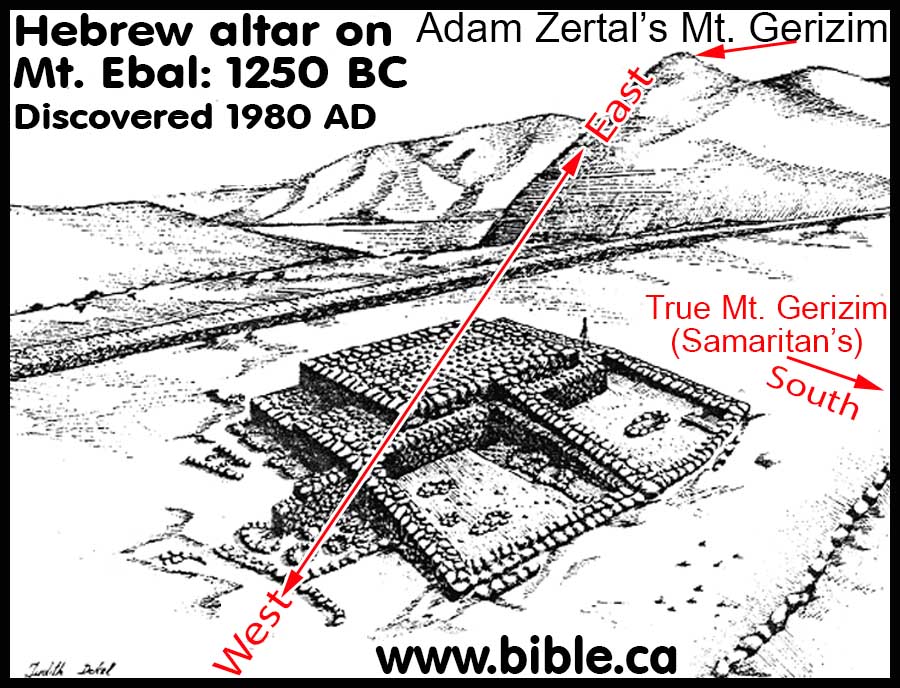

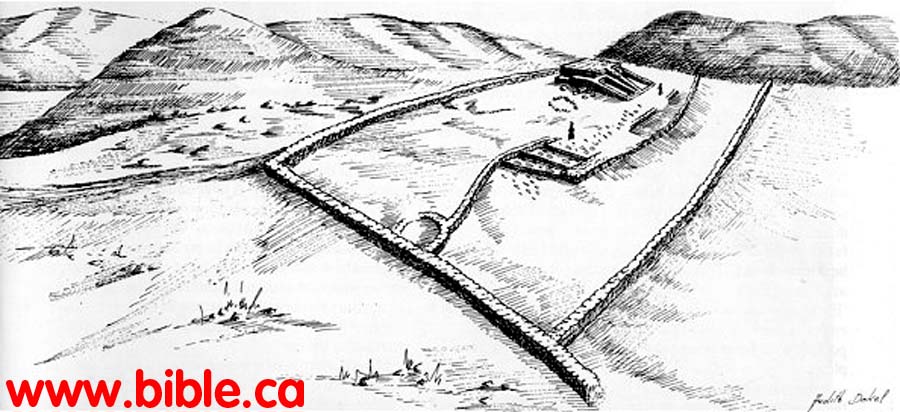

4. The site at Mt. Ebal had two occupation levels. Zertal calls the older occupation "level II" which he dates ~1300-1270 BC and the younger level I to 1250 BC.

a.

If this site is no older than 1300 BC, then none of it could be built by

Joshua, because the exodus took place in 1446 BC.

However, this is a Hebrew altar built during the time of Deborah the Judge and

underneath we believe is the actual altar of Joshua that should be dated to

1406 BC since a scarab from Tuthmoses III was found but wrongly dated to 1250

BC.

b. "SUMMARY: A small cult site for offering sacrifices was established here in stratum 2. As evidence. the excavator cites the finds uncovered beneath the main stratum IB structure and the burnt areas, which contained animal bones. A four-room house adjoining the cult center was apparently the residence of its attendants. Because of the small size of the site in this stratum, it is assumed that it served as a family or tribal cult site. The excavator similarly interprets the stratum 1B remains as a main cult site of the Israelite settlers. Confirmation of this view is provided by the absence of dwellings. the presence of stone installations containing offerings, the singular architectural plan, and the ashes mixed with animal bones. The large double enclosure and the finely built main structure are in this stratum: The latter was apparently intended to serve as the focal point of ceremonies for a large assembly. The enclosure and the main building were abandoned after several decades of use and covered with a layer of stones (stratum IA). This was probably done deliberately, to bury the site. This interpretation of the site has aroused a great deal of controversy among scholars. Whereas the excavator viewed the main building as a large sacrificial altar, N. Na'aman identified the area as Shechem's main cult site in the Iron Age I—namely, as the "Tower of Shechem," and interpreted the central enclosure as the "house of El-berith" (Jg. 9:46). Some scholars (A. Mazar, M. D. Coogan, I. Finkelstein) agree that the site has a cultic nature but do not interpret it as an altar; others (A. Kempinski, A. F. Rainey) reject cultic interpretation of the Mount Ebal remains and tend to view the structure as a fortified tower." (Adam Zertal, New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavation in the Holy Land, Mt. Ebal, 1993 AD)

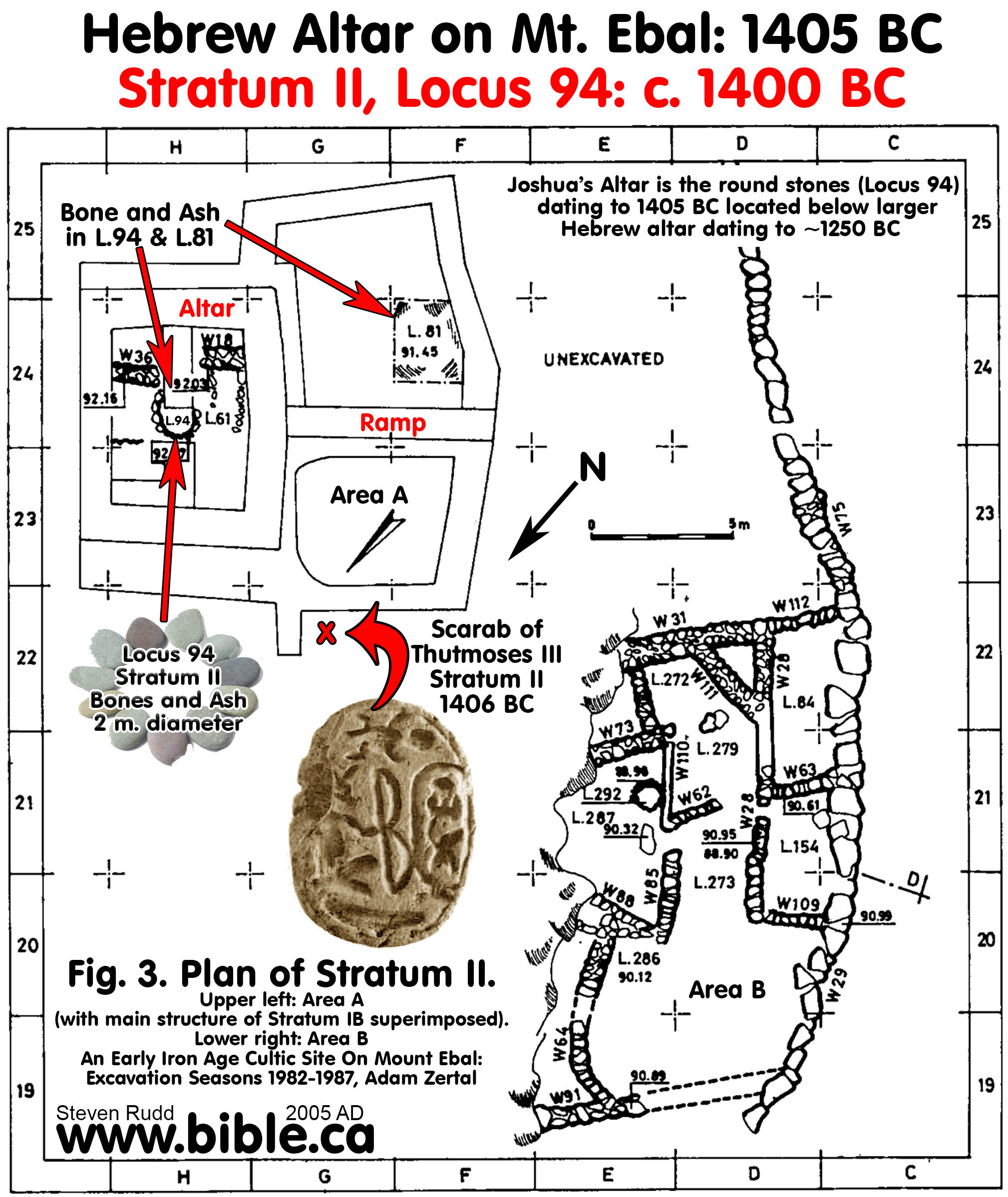

5.

Adam Zertal’s excavation top plan of Stratum II: 1406 BC (our date,

Zertal dates it to 1270 BC)

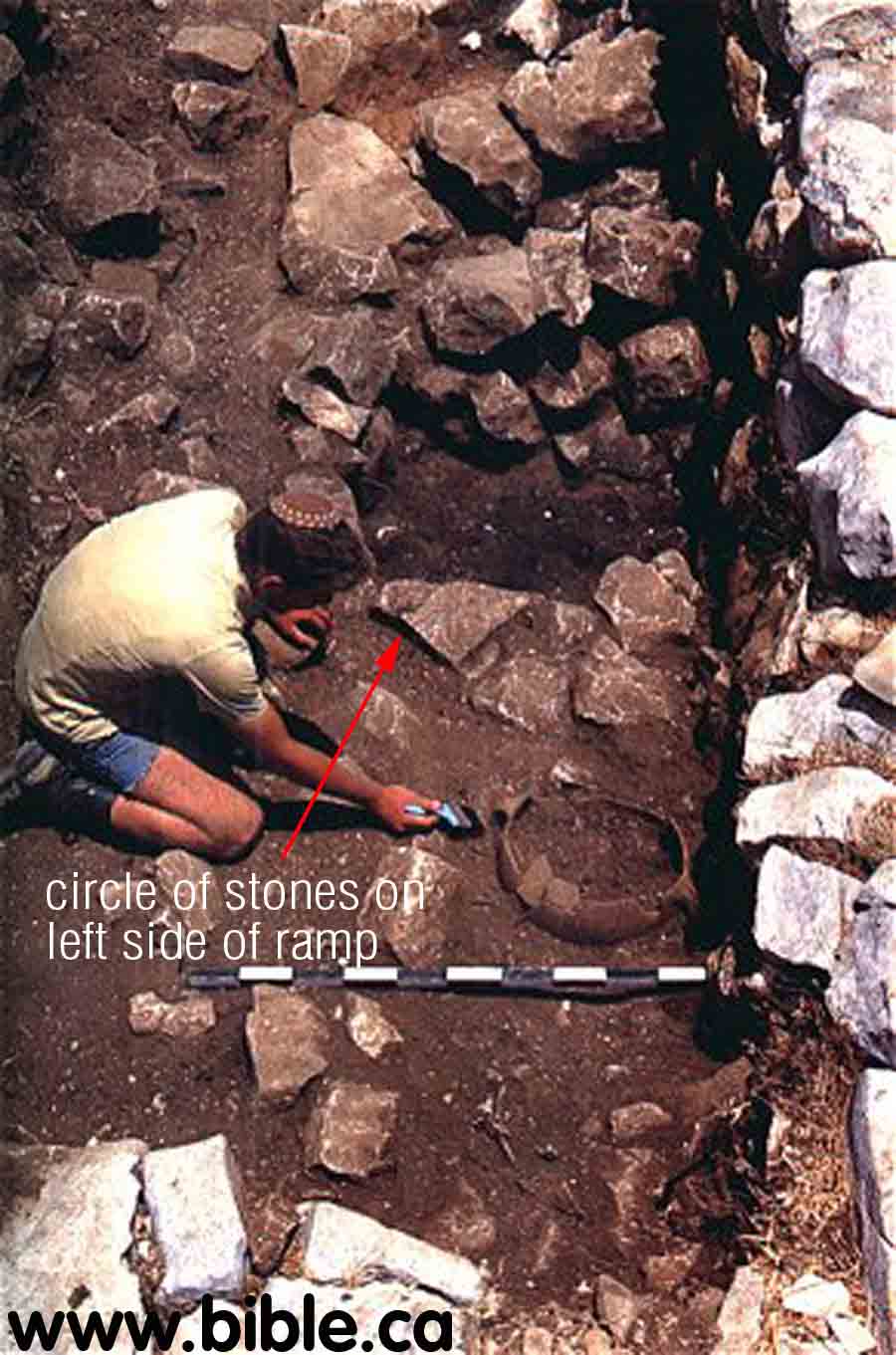

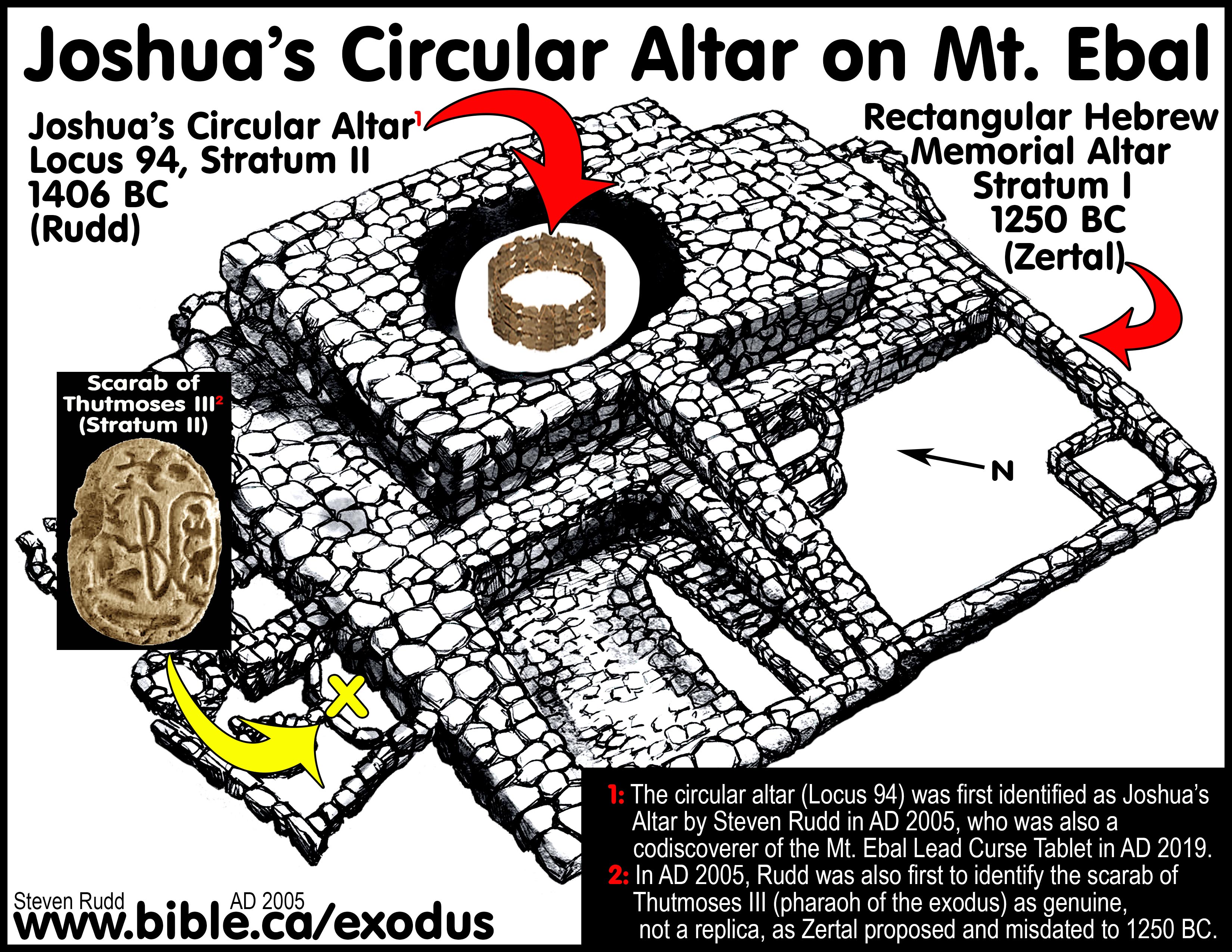

a. Joshua’s altar is the round circular altar (locus 94, Stratum II) is directly below the younger square altar.

b. In the round altar were found burnt bones and ash. The round altar is in the exact geometric center of the square altar platform where sacrifices were made. We speculate that since Abraham and Isaac lived in the area and built altars, we believe that the site dates back to the time of Abraham and that Joshua built his altar on top of Isaac's who in turn built his altar on top of Abraham's. In other words, the site has a long tradition of use as an altar from 2000 BC down to 1250 BC.

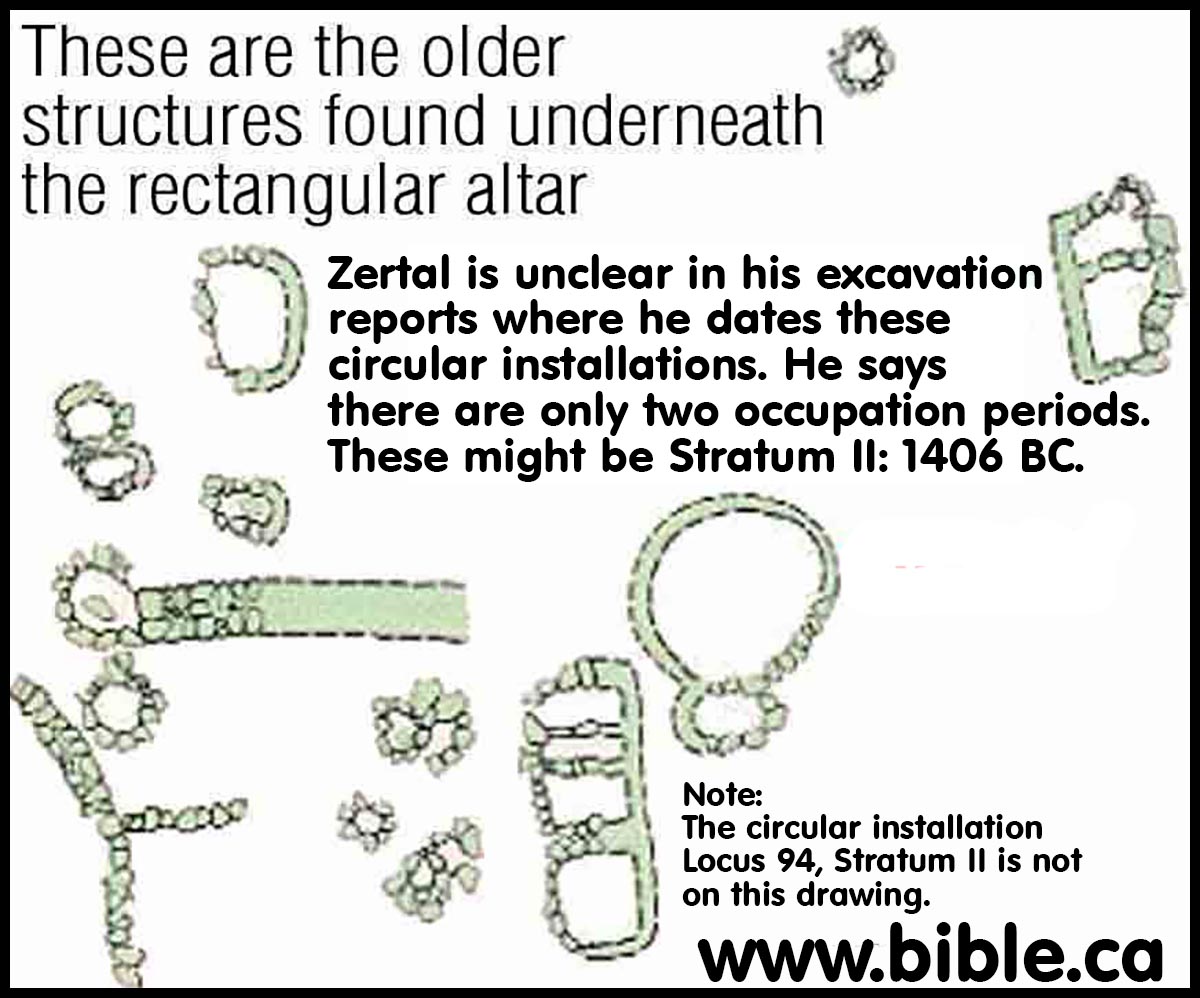

2. Zertal

identified only two occupation levels, so he may have assigned the other

circular installations seen on the Stratum I top plan to the wrong phase and

should be on the Stratum II top plan.We agree that there are

clearly two occupation levels. The rectangular altar we see today was built

about 1250 BC. The 2 meter (6.5 foot) diameter circular stone structure with

burnt kosher bones inside was is located directly beneath the rectangular altar

and was built about 1406 BC by Joshua. (We call it an altar, Zertal does not.

We date it to 1406 BC, Zertal dates it to ~1270 BC)

.

.

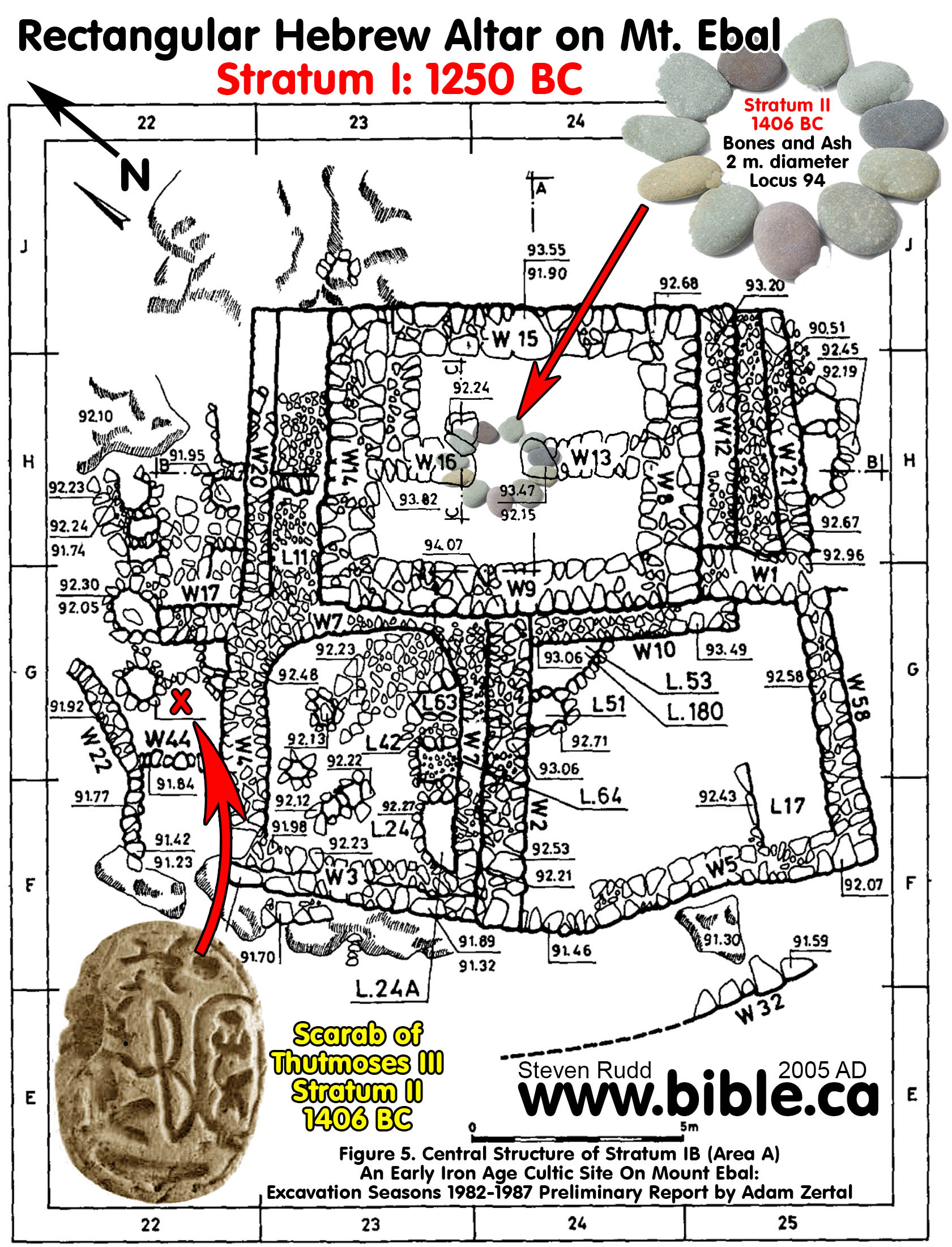

6.

Adam Zertal’s excavation top plan of Stratum I: 1250 BC (our date,

Zertal also dates it to 1250 BC)

a. Zertal identified only two occupation levels, so he may have assigned the other circular installations seen on the Stratum I top plan to the wrong phase and should be on the Stratum II top plan. Since Zertal dated the rectangular altar to ~1250 BC, it cannot be Joshua’s altar because the conquest started in 1406 BC and Joshua build his altar on Mt. Ebal in 1406 BC. The rectangular structure, therefore, may be either a later memorial altar of the earlier round altar of Joshua.

b. This altar is not oriented east but points to the four corners of the compass. This is strange for a Hebrew altar.

3. ADAM ZERTAL NEVER SOLVED THE PUZZLE: Zertal wrote a manuscript that was posthumously published after he died in AD 2016. Although Zertal identified some connection between the circular altar that underlay the rectangular altar, he never realized that Joshua’s altar was the circular altar. Zertal had all the information he needed to identify the circular altar as Joshua’s altar, but his Achilles heel was his late date of the exodus in 1253 BC under Rameses II. This massive error in chronology forced him to conclude the circular altar was part of a pre-Israeli homestead. Zertal noted the obvious connection of the rectangular altar being built over top of the exact epicenter of the circular altar, calling it “primogenial ritual site on Mount Ebal”. Zertal was puzzled by this connection, but never solved it by realizing the exodus was in 1446 BC with Thutmoses III as the pharaoh of the exodus. Steven Rudd even communicated with Adam Zertal about all this, but he went to his grave as an advocate of the late date of the exodus (1250 BC) and promoting the rectangular altar of Joshua’s altar and the circular altar as part of four room house that predated the arrival of Joshua by 25-50 years. The solution is simple, the circular altar is the original Joshua’s altar in 1406 BC and the rectangular altar was built during the period of the Judges around 1250 BC as a memorial altar. Zertal would have easily solved this puzzle had he adopted the early date of the exodus in 1446 BC.

a. “The builders of the monumental bamah must have known about the earlier construction, since they had no qualms about destroying a portion of it during their own building process. The two strata are identical in their cultural typology and the years that separated them were not very numerous. Both were peppered with the remains of collared-rim pithos, and the rest of the pottery fragments were also very similar. The central platform was built close on the heels of the lower phase and in relation to it. Digging deeper, we noticed that these two strata, so close in time, were quite distinct in character. At the geometric center of the bamah's floor, a circular structure two meters in diameter and constructed of medium-sized stones was discovered directly above the bedrock. Though erected later, the bamah's internal partitions encroach upon this circular structure to some extent. Like the bamah above it, this too had been filled with pure ashes mixed with bones. It would be some time before we'd realize that this was indeed the core, the very heart of the ritual within the ancient structure. This was it- the primogenial ritual site on Mount Ebal.” (A Nation Born book, Adam Zertal, Zertal’s Manuscript: 1990 AD, published: 2018 AD)

b. “There are several pieces of evidence which connect the altar with the earlier circular installation. First, the altar was erected directly above the installation, which stands precisely in the geometric center of the larger altar above it. From this we can infer that the builders used the installation as a kind of template upon which they laid out their altar. Furthermore, the pottery fragments found within the two stages are virtually indistinguishable. Finally, the first of our scarab seals (discussed in chapter four) was found in the altar's fill, or more precisely, in the heap of ashes and refuse beside the southeastern corner of the altar. This heap spilled out of the altar when part of the structure was destroyed in an earthquake. Parallel seals have been found in Egypt, the biblical Land of Israel and Transjordan, and these indicate that our scarab was produced during the final third of the reign of Ramses II. A second scarab, found in the overlying main stratum, was from the same date. The two scarabs were both produced sometime between 1240 and 1210 B.C.E. This clearly demonstrates that there was no time gap between the two phases.” (A Nation Born book, Adam Zertal, Zertal’s Manuscript: 1990 AD, published: 2018 AD)

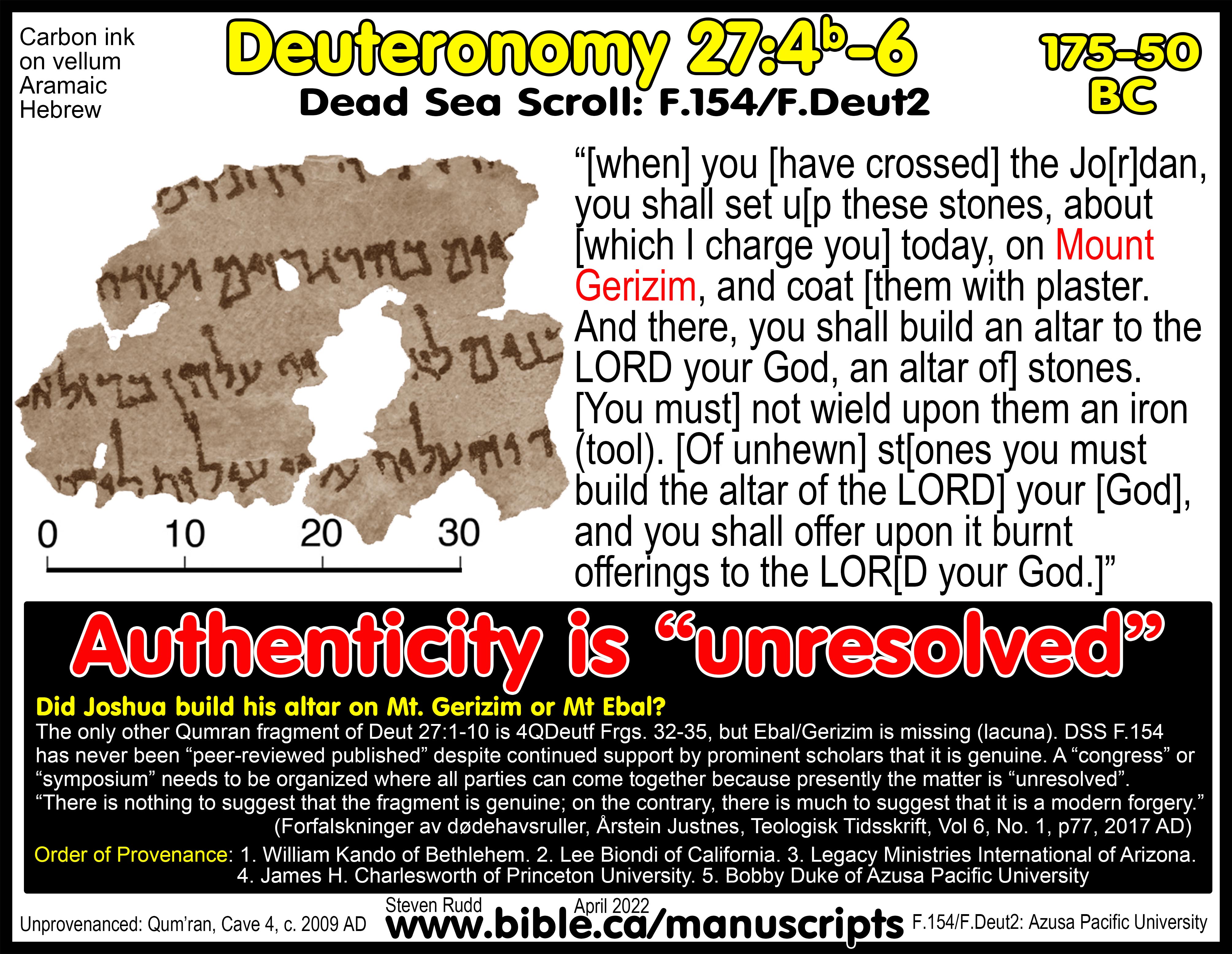

7. Warning—Possible forgery: Recently discovered Hebrew Dead Sea Scroll (4QDeut?) at Cave 4 in Qumran supports the ancient Samaritan view that Joshua built his altar on Mt. Gerizim, not Mt. Ebal.

|

Joshua’s Altar on Mt. Gerizim? See detailed outline on this Dead Sea Scroll from Qumran, cave 4, that reads “Gerizim” instead of “Ebal”. (4QDeut?)

While inherently speculative, the Samaritans may have built their Samaritan Temple on Mt. Gerizim to venerate Joshua’s Altar! |

A. Archaeology of Joshua’s Altar:

1.

Steven Rudd personally met Adam Zertal at the very site

of Joshua's Altar where he discussed the find under the watchful eye of an IDF

ground army escort including F-16s in November 2004. Trips are often thwarted

by the terrorists in the area. One ill-fated tour, in October 2000, ended with

the death of Rabbi Binyamin Herling, one of several hikers who left the main

route and were shot at by Palestinian terrorists in Shechem. The army was

widely accused of not taking offensive action to save the hikers when the

terrorists pinned them down with long-range but accurate fire. A later trip to

the same area during Chanukah was canceled by the army with just two days

notice, because of intelligence warnings of another planned terror attack. On

October 7, 2000, Joseph's Tomb, the third most holy place in Judaism, was

destroyed by Muslims. It is located east of modern Nabulus between Shechem (Tel

Balata) and Sychar at the foot of Mt. Ebal. It had come under attack and the

Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) withdrew after gaining reassurances from the

Palestinian Authority (PA) that they would protect the site in accordance with

their obligations under the Oslo Accords to protect holy sites. Two hours after

the withdrawal Muslims began destroying the site. Joseph’s Tomb was burned and

torn down stone by stone, then bulldozed. It was immediately declared a Muslim

holy site. I was extremely fortunate and privileged to be one of the first to

visit Joshua’s Altar in AD 2004, although the army did cut short my visit for

"security reasons". I also assisted in reconstruction of the outer

temenos wall of the altar under Adam Zertal’s personal supervision.

.

.

2. In a discussion with Adam Zertal, he said that this archeological site has made a Bible believer out of him. Amen! Adam Zertal has undergone a transformation of faith that is truly remarkable. Like most of his fellow Israeli archeologists, he did not believe the Bible stories of the exodus to be true. He told me directly that the most anti-Biblical forces in archeology are the professors in the various Universities in Israel. Many Christians and Jews are surprised that this would be the case. Palestinian Muslims quote these Israeli archeologists in Tel Aviv as proof that the idea of a Jewish homeland that dates back to 1406 BC is a myth. Zertal was one of these Bible trashing archeologists. But that all changed in 1983, three years after Zertal first stumbled on the site while doing a formal archeological survey of the area. After studying the structure for three years with no idea what is was used for, he suddenly realized that it was the site of Joshua's Altar. We agree with him and now he believes the Bible. See our section on, "They are digging up Bible stories!"

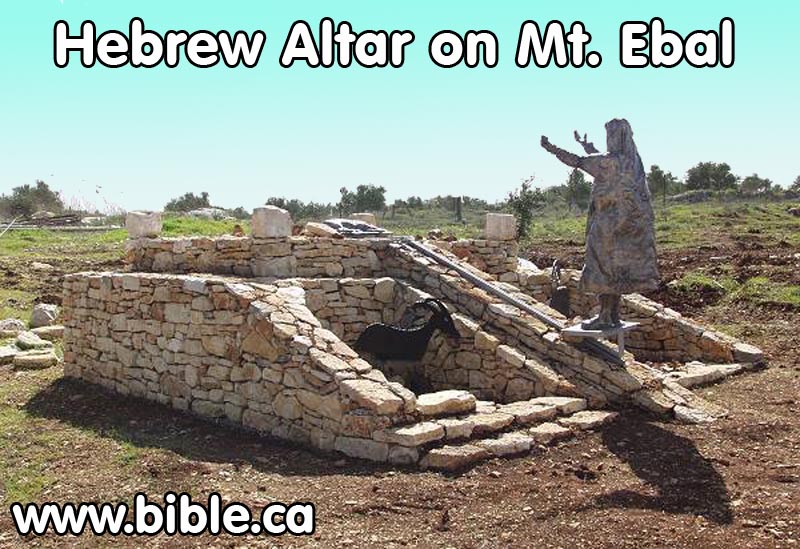

The Hebrew altar on Mt. Ebal as seen today. Reconstruction at Garden of

Biblical Samaria Park

3.

Adam Zertal commented: "We discovered this place, all

covered with stones, in April 1980. At that time I never dreamt that we were

dealing with the altar, because I was taught in Tel Aviv University - the

center of anti-Biblical tendencies, where I learned that Biblical theories are

untrue, and that Biblical accounts were written later, and the like. I didn't

even know of the story of the Joshua's altar. But we surveyed every meter of

the site, and in the course of nine years of excavation, we discovered a very

old structure with no parallels to anything we had seen before. It was 9 by 7

meters, and 4 meters high, with two stone ramps, and a kind of veranda, known

as the sovev, around."

4. The exodus happened in 1446 BC and the Pharaoh of the exodus was Tuthmoses III. However, there is a problem, because Adam Zertal dates the exodus at 1250 BC, when the Bible tells us it was 1446 BC. 1 Kings 6:1 says that Israel was at Joshua's Altar in 1406 BC. The structure we see today simply cannot be Joshua's altar since it is dated to 1250 BC.

5.

Zertal discovered a second circular structure 6.5 feet

in diameter underneath what we see today. Zertal dates this second structure to

1300 BC but we question this. We have superimposed the circle of stones onto

the drawing so you can see what it looked like. These stones were on bedrock

level underneath the altar we see today. We call this circle of stones an

"altar", although Zertal does not. However, he does document that

burnt bones found inside of it.

6. Hebrew altars can be distinguished from pagan altars in 5 respects: 1. They are made of uncut natural stone. 2. Ramps, never stairs. 3. Hebrew altars are square. 4. Hebrew altars have their sides oriented to the 4 points of the compass (NSEW), as we see in the orientation of the tabernacle. It is clear that Adam Zertal has discovered a Hebrew altar because it is made of uncut stones with ramps. However since the altar is rectangular and the corners, not the sides point NSEW, this site presents some challenges. We believe this mix of pagan and Hebrew elements of the rectangular altar of 1250 BC can be explained. This was the time of Deborah the Judge and perhaps this altar was built by Hebrews to worship to both YHWH and a pagan god. Perhaps the mix of Hebrew and pagan elements in the altar are typical of such times of compromise. "Then the sons of Israel did evil in the sight of the Lord and served the Baals, and they forsook the Lord, the God of their fathers, who had brought them out of the land of Egypt, and followed other gods from among the gods of the peoples who were around them, and bowed themselves down to them; thus they provoked the Lord to anger. So they forsook the Lord and served Baal and the Ashtaroth." Judges 2:11-13

7.

Adam Zertal refined his views of the two level of

occupations at the Mt. Ebal site. In 2004 Zertal dates the rectangular altar to

1250 BC. "More important, however, is that they

[the pottery discovered] fix a date for the construction of the altar -

approximately 1250 b.c.e." (Adam Zertal). In 1986: "Zertal

calls the older occupation "level II" which he dates 1225 - 1200 BC

and the younger level I to 1200 -1150 BC. Zertal also uncovered a raised step

behind the courtyards, which he assigns to Level II. "Animal bones from

Level II have been found in the area of the courtyards; these bones are not burnt

and thus are probably the remains of meals, not sacrifices. Cultic

installations in the area of the later altar are also attributable to this

early phase. In Level I (the later phase), many new structures were added

(tinted red). The Israelites constructed a thin stone wall parallel to the old

revetment wall. They filled in the space between the Level II revetment wall

and the Level I wall with medium-size stones to make a sturdy temenos wall that

supported the courtyards. At the same time, says Zertal, they built the altar.

Surrounding the inner temenos, the altar and the courtyards, an outer temenos

wall was constructed. Entrance to this larger walled area was from an opening

on the southeast. A three-stepped entrance from the west in the inner temenos

wall gave access to the altar area." (How Can Kempinski Be So Wrong!, Adam

Zertal, BAR, 1986 AD)

Since 2004, Zertal now dates level II to 1250 BC.

8. Amazingly, Zertal has already discovered the proof he needs to date the site to the 1406 BC. He discovered the cartouche of Tuthmoses III at the site. (see below). Tuthmoses III was the pharaoh of the exodus.

B. AD 2019 Mt. Ebal Curse Tablet: “Defixio” by Steven Rudd, March 2022

Earliest Hebrew inscription on Earth. | Earliest Hebrew use of YHWH on Earth

“That with an iron stylus and lead they were engraved in the rock forever!" (Job 19:24)

Introduction:

|

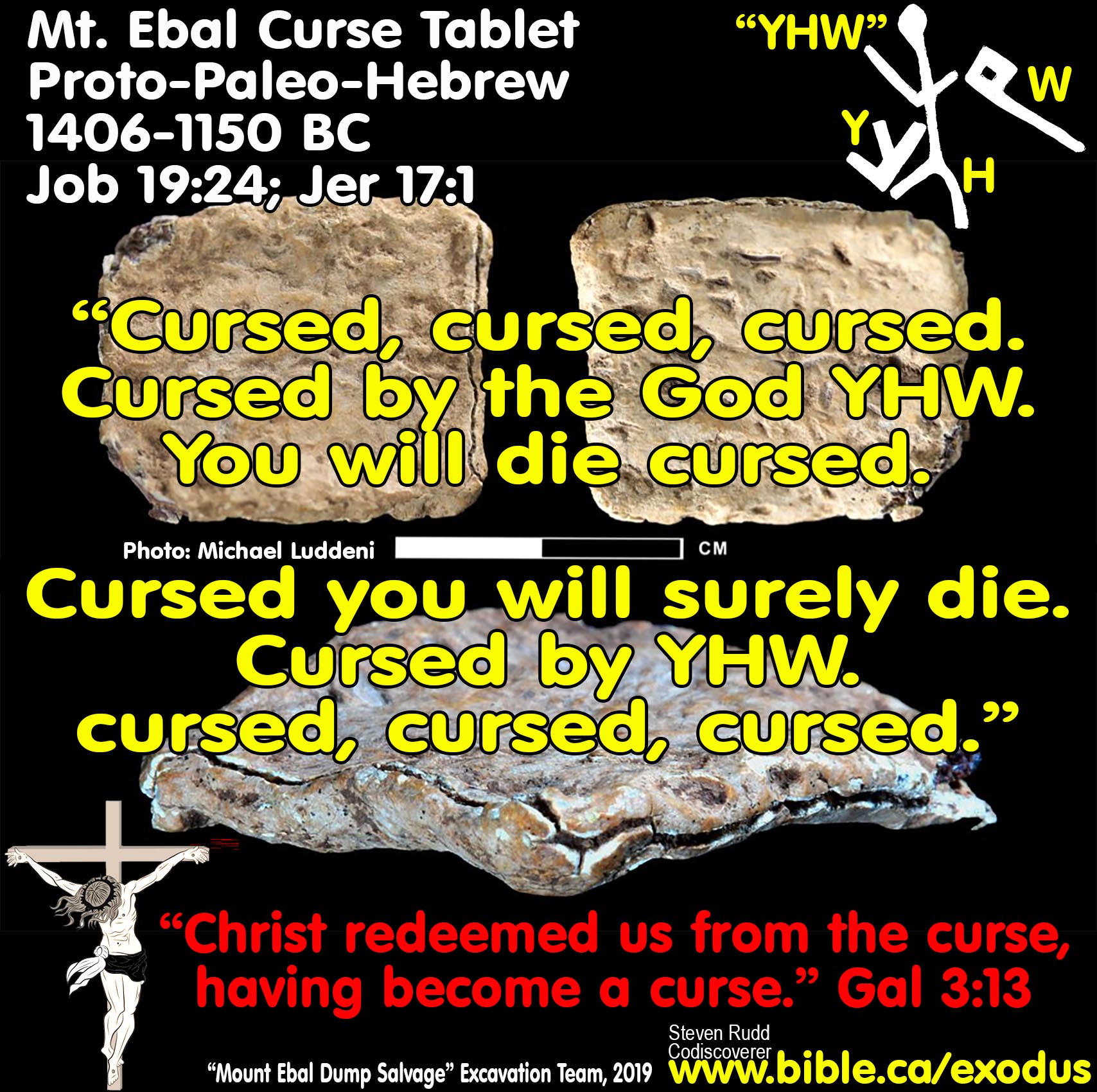

The AD 2019 discovery of the Late Bronze Age lead curse tablet on Mt. Ebal, which the Bible identifies as the mountain of curses, is a Bible skeptic’s worst nightmare because it is an alphabetic Proto-Paleo-Hebrew script that utilizes a complex and sophisticated chiastic poetic parallel with 10 curses, to express a legal verdict echoing Gen 2;17, “you shall surely die”, that includes God’s name “YHWH” twice, in the same format as a contemporary Late Bronze Age Hittite submission covenant, embedded like a sealed letter inside an folded outer envelope, in the same time, place, and message as would be predicted by scripture. “That with an iron stylus and lead they were engraved in the rock forever!" (Job 19:24) |

I. The importance of the AD 2019 Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet:

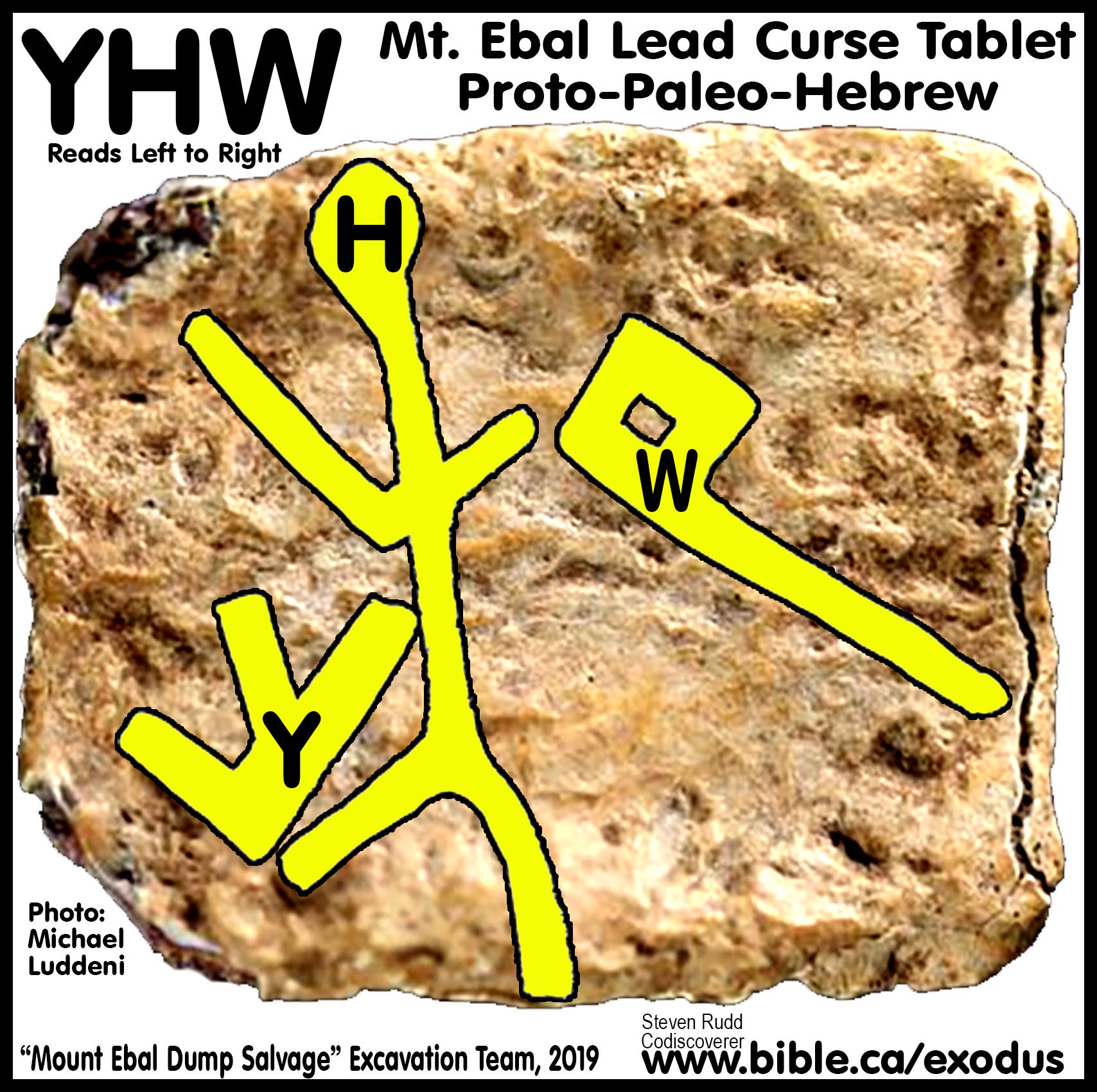

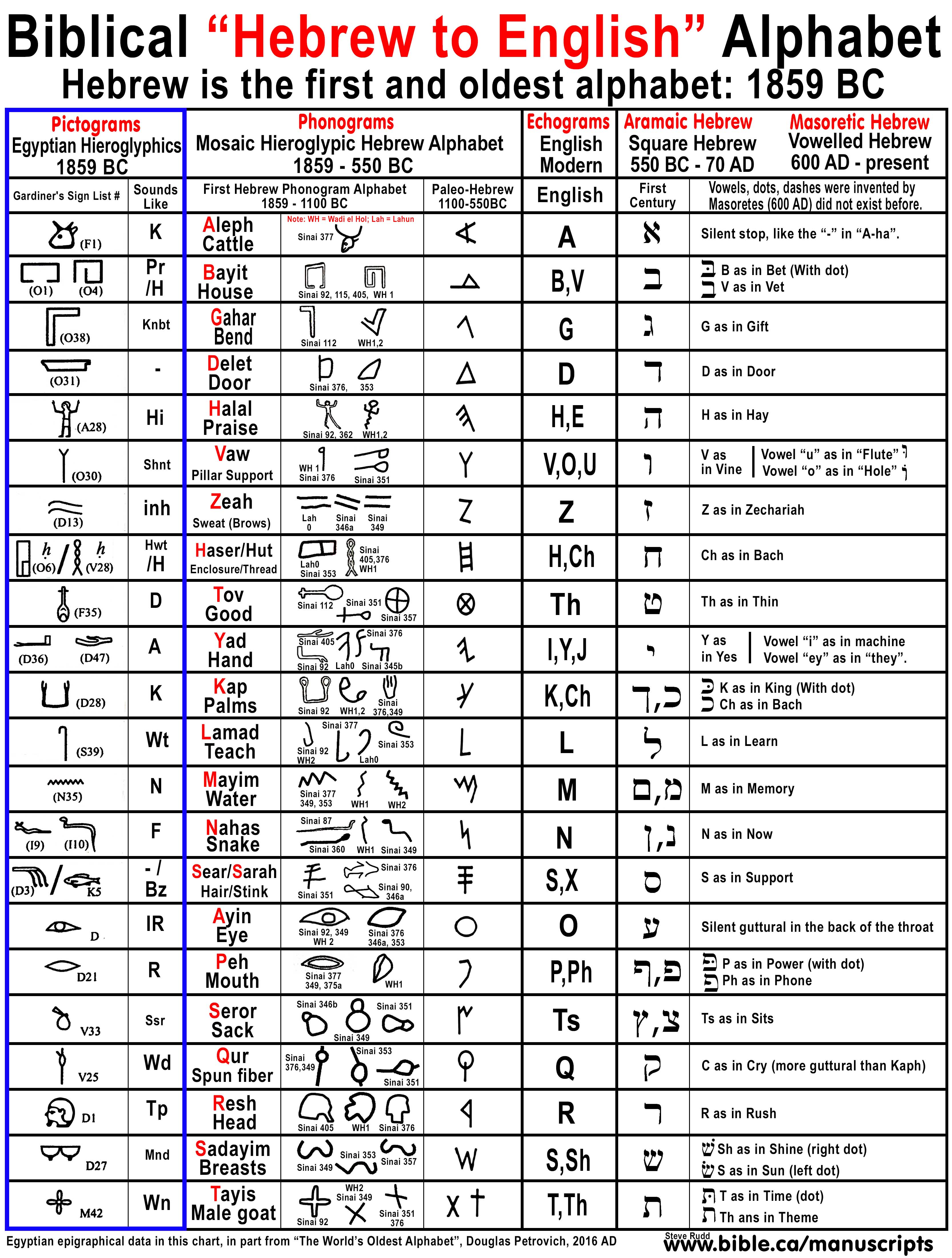

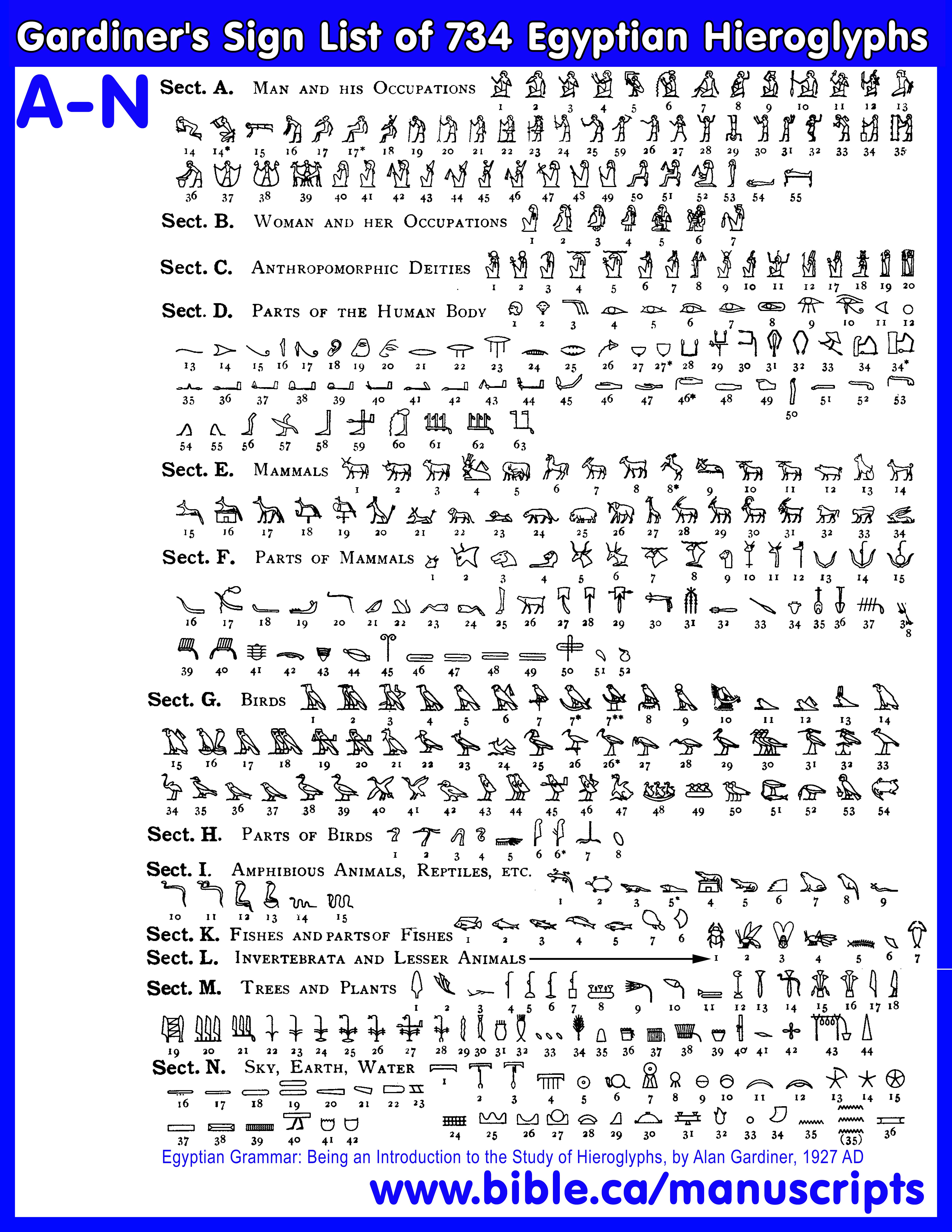

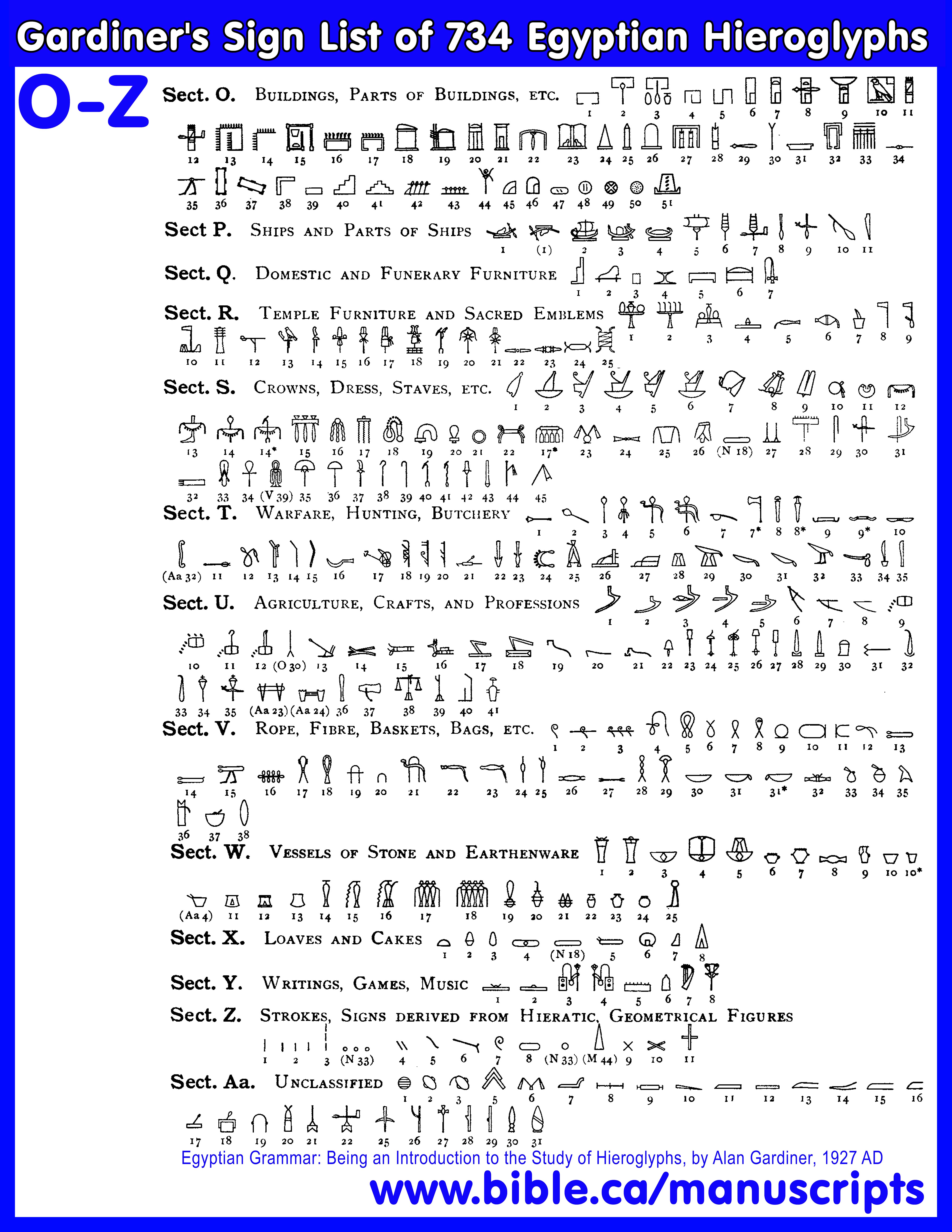

1. The script of the Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet dates to the Late Bronze Age: 1406-1100 BC. Three key epigraphic features the script unquestionably date the Lead Curse Tablet of Mt Ebal to the Late Bronze Age as a proto-Paleo-Hebrew script.

a. First, the Hebrew letter “H” (halal/praise) is represented twice in the name of God (YWH) with the graphical symbol of a man with his hands raised over his head in worship which was directly borrowed from Egyptian Hieroglyphics.

b. Second, the Hebrew letter “A” (aleph) is represented 11 times using the graphical symbol of an ox head which was directly borrowed from Egyptian Hieroglyphics.

c. Third, the Hebrew text reads left to right, placing it in the period before 1100 BC, after which, the script became standardized reading right to left by Samuel through his work at his prophet’s school at Naioth around 1050 BC (1 Sam 19:18-24). The earliest Hebrew, Egyptian, and Phoenician scripts were read left to right, right to left, top to bottom, bottom to top, or as the ox plows.

2. Oldest

Hebrew text: There were four historic Hebrew scripts, and the lead curse

tablet is from the earliest family known as Hieroglyphic-Hebrew, also called,

Proto-Paleo-Hebrew. Joseph invented the first alphabet by adapting the symbols

from Egyptian Hieroglyphs as the basis of the 22 characters of the Hebrew

alphabet. It can be proven that all alphabets today, including English, were

directly derived from this original Hebrew alphabet. The transition from

Hieroglyphic-Hebrew to Paleo-Hebrew occurred under the oversight and direction

of Samuel at his prophet’s school Naioth around 1050 BC. It was Samuel who

standardized the Hebrew script used by David and Solomon down to the Babylonian

captivity when Paleo-Hebrew script went extinct. Under the oversight and

direction of Ezra in 458 BC, Aramaic Hebrew, also known as “Square Hebrew”

replaced the Paleo-Hebrew script. Aramaic Hebrew was the script of the Dead Sea

Scrolls and the script used today in modern Israel. The curse tablet predates

the oldest known Hebrew text by 200-475 years. Currently, the oldest Hebrew

script is from the Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon which is dated to between 1010-923

BC.

|

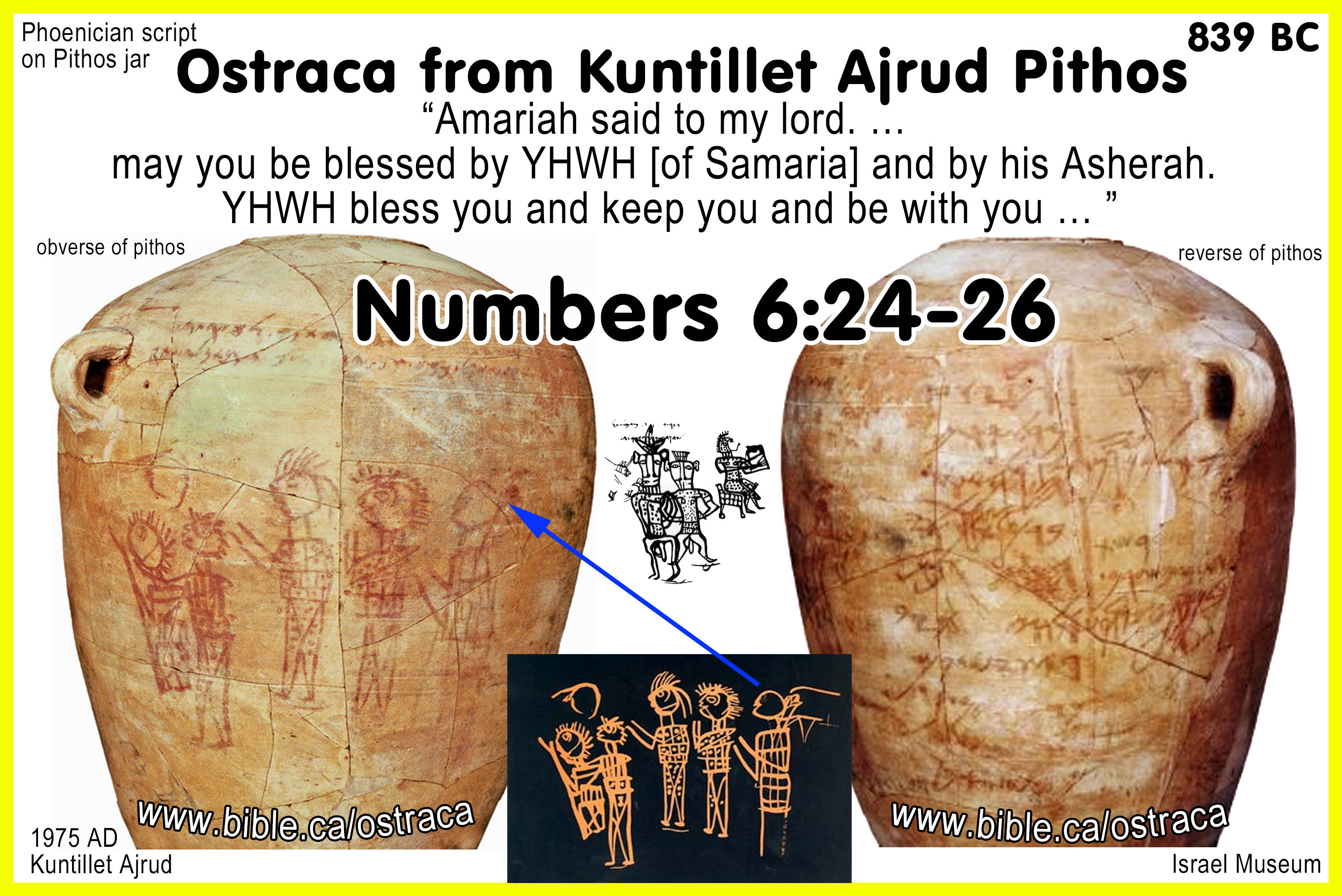

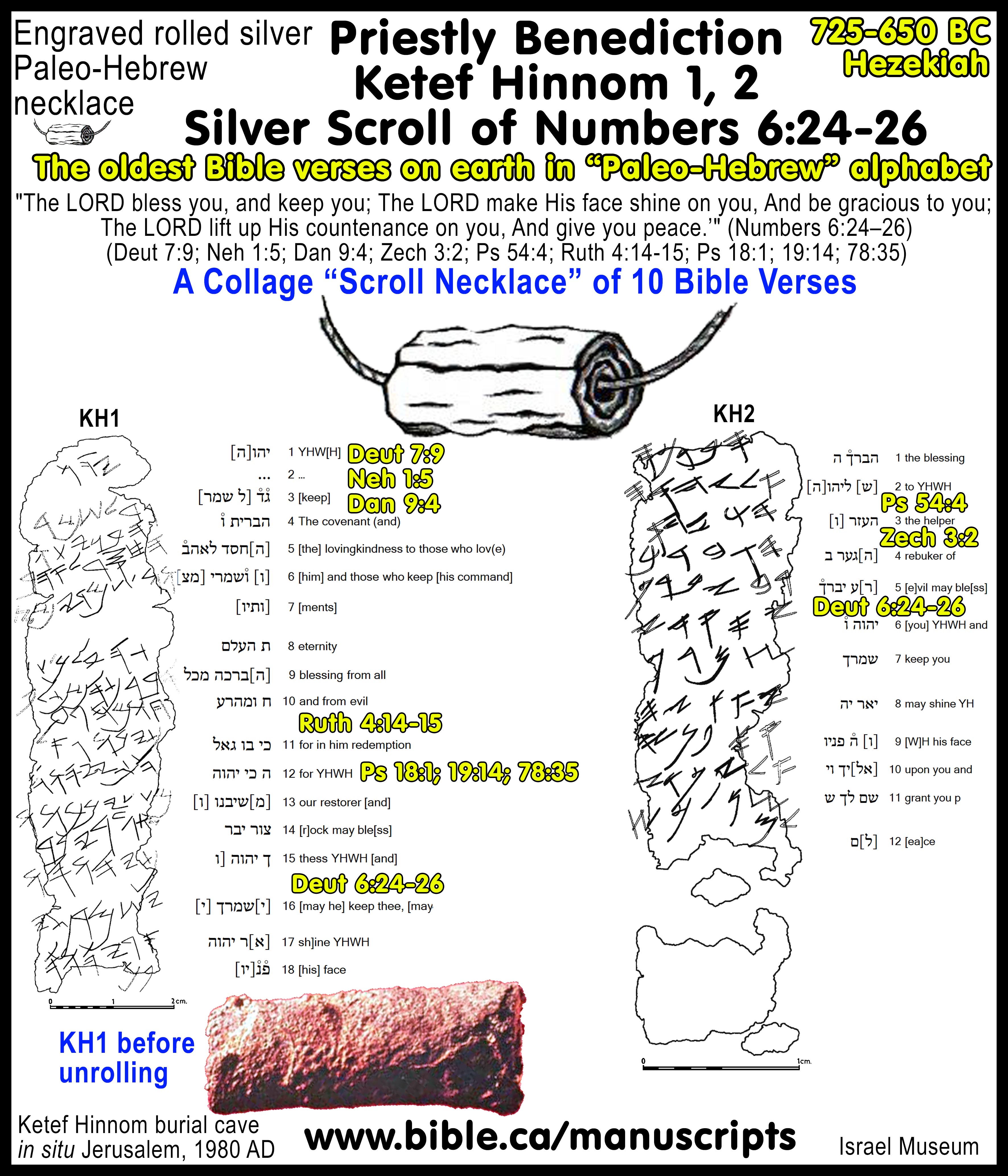

3. Oldest use of YHWH: Twice the curse table uses the three-letter “YHW” for the name of God. The curse tablet predates the oldest known Hebrew use of YHWH by 300-575 years. Currently, the oldest Hebrew text that contained YHWH, is the Kuntillet Ajrud ostracon which dates to 839 BC. Kuntillet Ajrud is currently the oldest Hebrew Bible text (Numbers 6:24-26) which predates the Ketef Hinnom silver scroll by 100-200 years. |

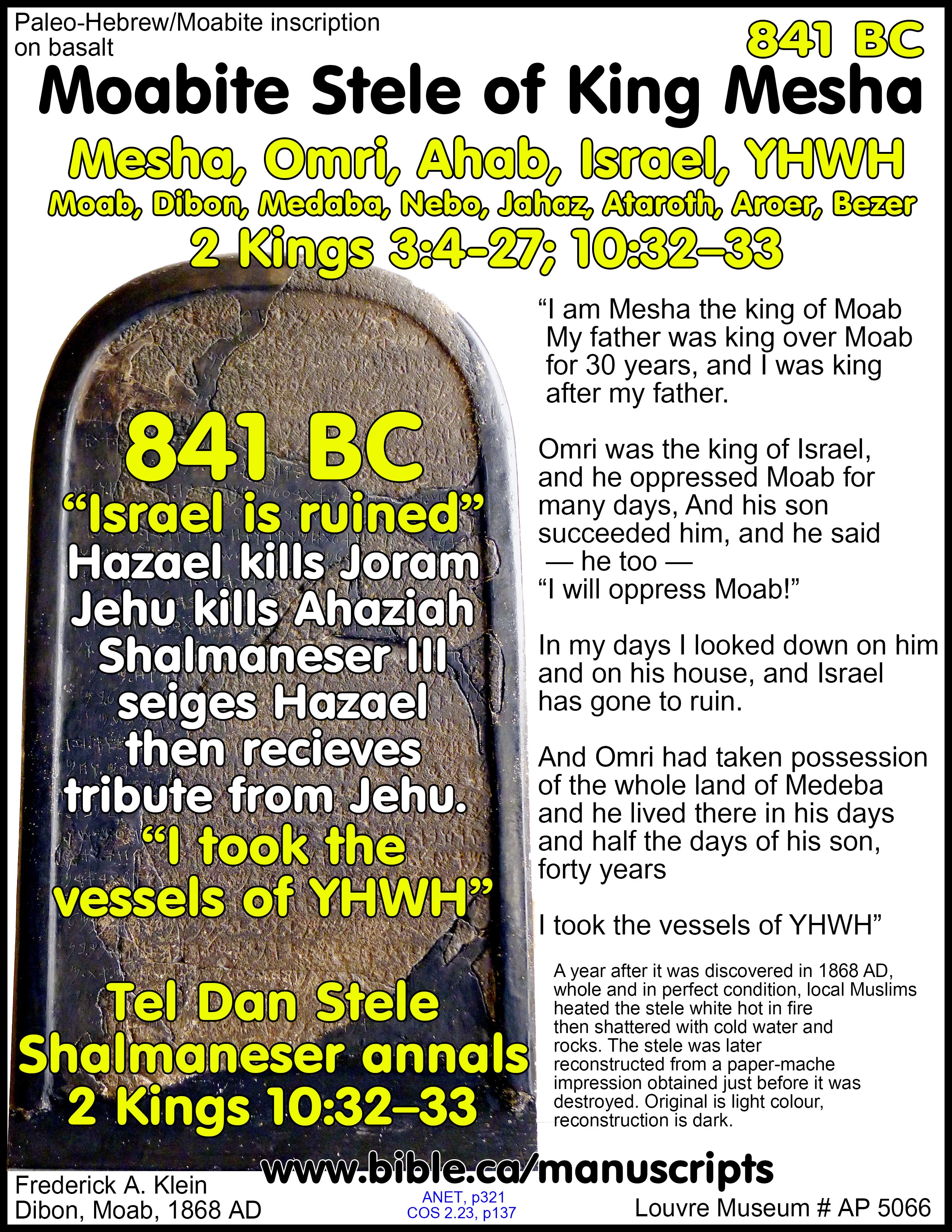

a. Four-letter spelling of YHWH:

i.

The common four-letter spelling “YHWH” used over 6500 times in scripture

is also used in the Moabite/Mesha Stele (841 BC). “I am Mesha the king of

Moab… Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, And his

son Ahab) succeeded him, and he said “I will oppress Moab!” In my days (941 BC)

I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin. … And

Chemosh said to me: “Go, take Nebo from Israel!” … I took it, and I killed

[its] whole population, seven thousand male citizens … And

from there, I took the vessels of YHWH” (Mesha Stone, 841 BC)

b. Two-letter: YH, YW

i. The two-letter spelling “YH” (Yah) is used in Exodus 15:2; 17:16; Ps 68:4,18

ii. The two-letter spelling “Yô or Yehô” is used in personal names like “Jochebed” meaning “Jehovah is glory” (Ex 6:20) and “Joshua” meaning ““Jehovah is salvation” (Ex 17:9)

iii. The double two-letter spelling “YH YH” is used in Isa 26:4

iv. The two and four-letter spelling used in combination “YH YHWH”: Isaiah 12:2; 26:4

v.

The two-letter spelling “YW” is used 9 or 10 times in the assemblage of

ostraca at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud (839 BC).

OLDEST BIBLE TEXT ON EARTH: Numbers 6:24-26. In AD 2017, Steven Rudd

identified from excavation reports, that the oldest bible verses ever

discovered was the from the assemblage of ostraca from Kuntillet Ajrud.

Currently the oldest Hebrew Bible text (Numbers 6:24-26) from Kuntillet Ajrud,

predates the Ketef Hinnom silver scroll by 100-200 years, which also quotes Num

6:24-25.

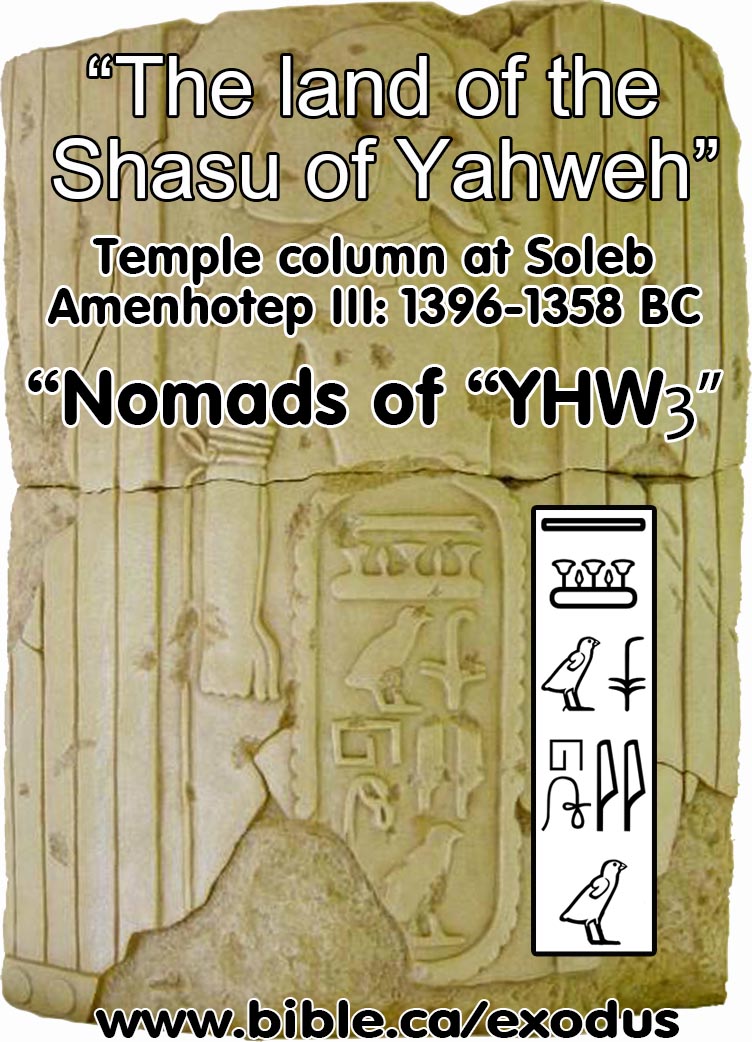

c. Three-letter spelling: YHW, YHH

i.

The three-letter spelling YHW is used in Soleb temple: “Shasu of Yhw”:

1396-1358 BC

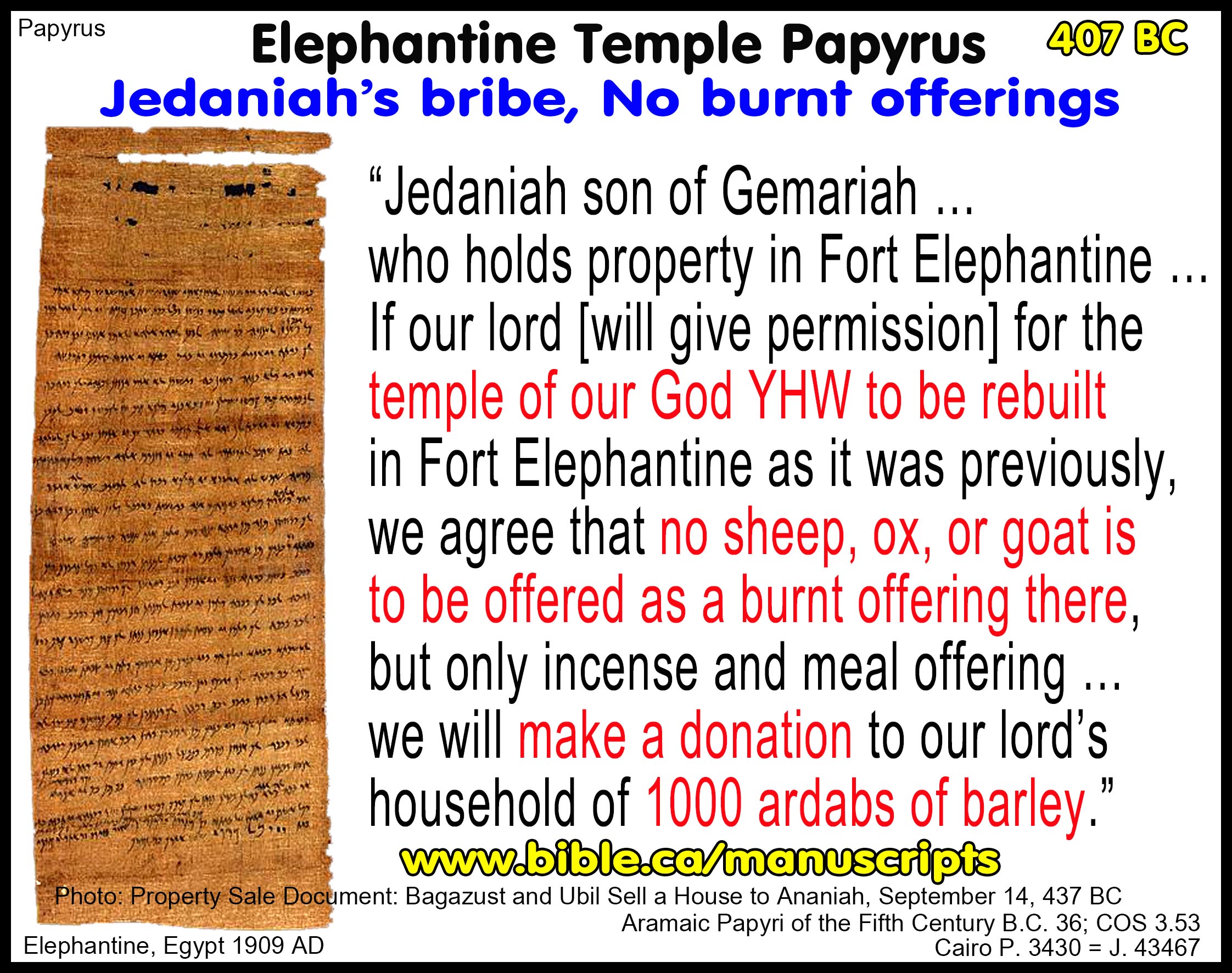

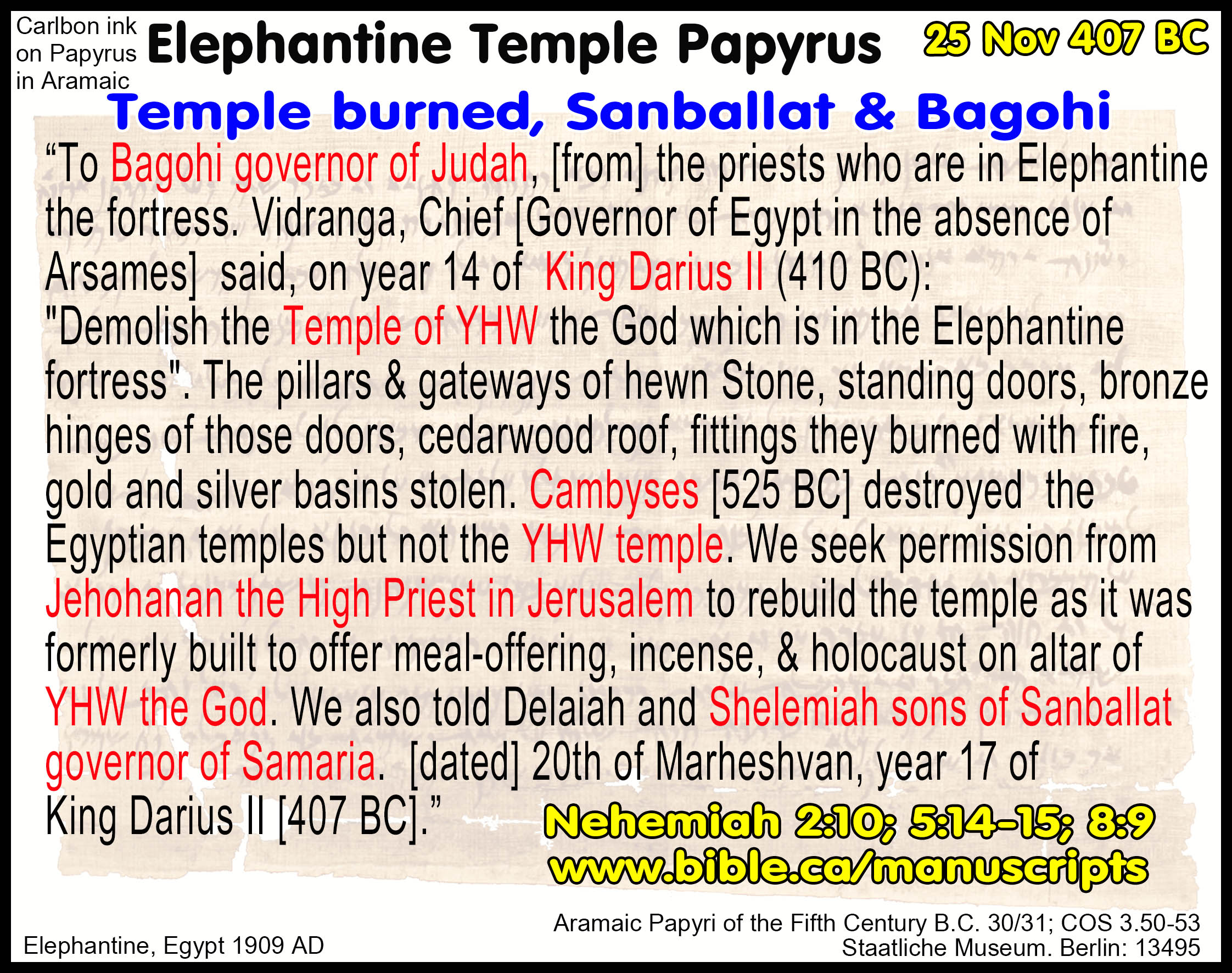

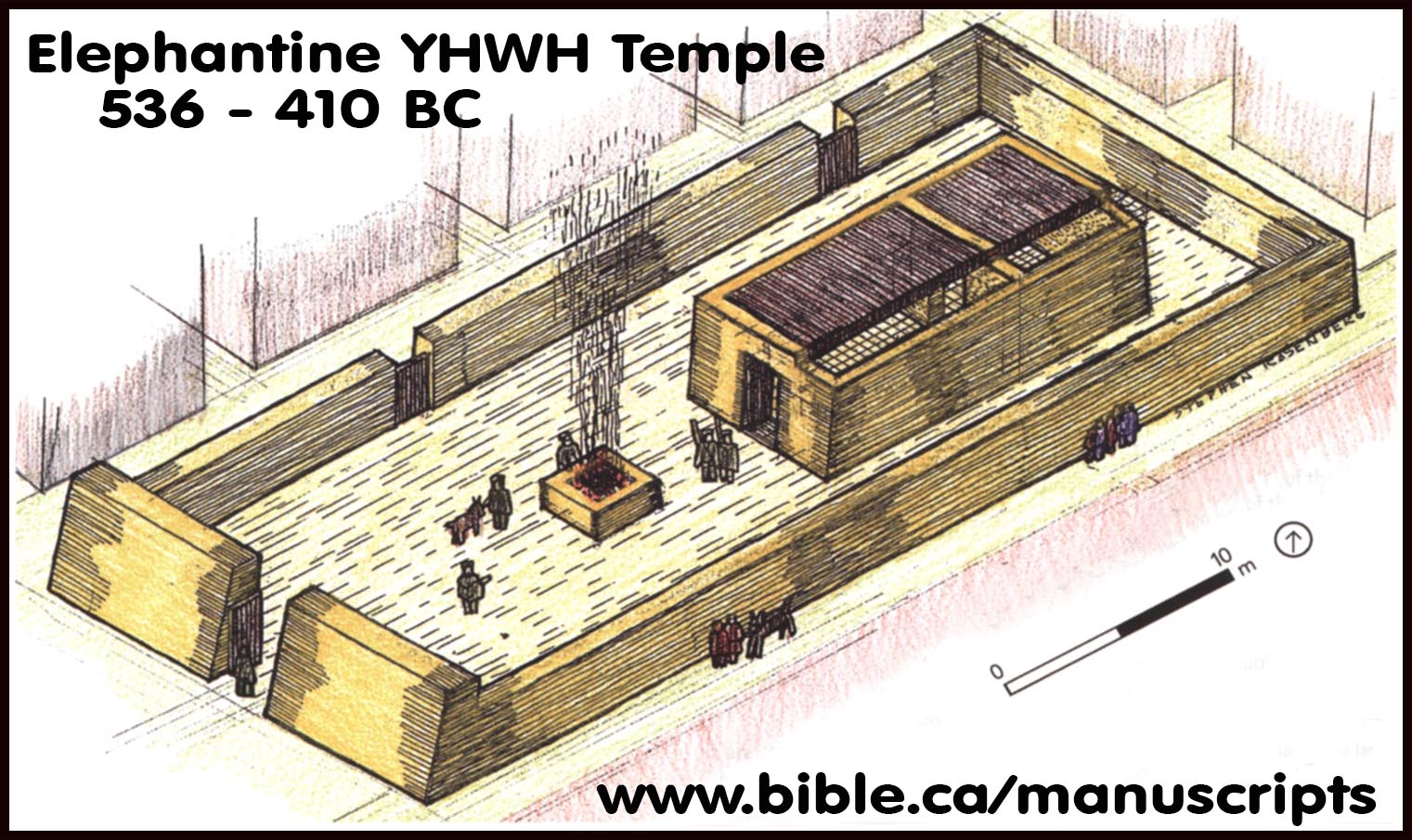

ii. The three-letter spelling “YHW” is used in the Aramaic Elephantine papyri: c. 400 BC

1. “YHW the God dwelling in Yeb.” (404 BC, Anani)

2. “Greetings to the temple of YHW at Elephantine” (Padua 1)

3. “Let us get rid of the temple of the God YHW in Fort Elephantine!” (“Text A” (AP 30)

4. “If our lord [will give permission] for the temple of our God YHW to be rebuilt 9in Fort Elephantine as it was previously, we agree that no sheep, ox, or goat is to be offered as a burnt offering there, but only incense and meal offering”. (AP 33, 407 BC)

iii. The three-letter spelling “YHH” is used in the Aramaic Elephantine papyri:

1. “Look after the tunic I left in the temple of YHH. Tell Uriyah it is to be dedicated.” (O. Cairo 49624, 475 BC)

2.

“May YHH [of hosts] bless you at all times.” (O. Clermont-Ganneau 186,

475 BC)

iv. Alexander Jannaeus used the three letter Paleo-Hebrew spelling “YHW” on his coins, 500 years after the Paleo-Hebrew script went extinct as a memorial of Israel’s beginning. His choice of the 3-letter spelling of the name of God in Paleo-Hebrew script confirms that it was considered a standard form.

1.

“Yehonatan the King” (78 BC). “Many of Jannaeus’ coins were overstruck

to replace “Yehonatan the King” with “Yonatan the High Priest and the Community

of the Jews,” eliminating both the royal title and the combination of letters

YHW, which could be read as the name of God. The restriking was probably done

after Jannaeus’ death, during the reign of Queen Salome Alexandra (76–67

B.C.).” (Dictionary of New Testament Background, Craig Evans, p223, 2000 AD)

4. The oldest lead curse tablet:

a. The metallurgy of the Mt Ebal Lead Curse Tablet dates to the Late Bronze Age matching 1406 BC. The metallurgy of the lead was analyzed at Hebrew university and was confirmed to originate from the famous Late Bronze Age Lavrion silver and lead mines in Greece from which many other lead objects are known to originate. The script on the Mt. Ebal curse tablet was inscribed with and Iron stylus on lead just as confirmed by the book of Job, where the story dates to the Early Bronze Age at the time of Abraham (Job 19:24; cf. also Jer 17:1).

a. Recently, Israeli archaeologists confirmed inscribed lead ingots were imported into Canaan from the Aegean region around 1400 BC, when they discovered in a ship’s cargo in a port south of Haifa. This lead has been analyzed and comes from the same Late Bronze Age Lavrion silver and lead mines in Greece as the Mt. Ebal curse tablet which dates to the same period.

b. Previously, the oldest known inscribed lead curse tablet was found in city of Selinus in Sicily which dated to the 5th century BC, which was a whopping 700-900 years younger than the Mt. Ebal lead curse tablet.

c. Previously, the oldest known inscribed lead strip was discovered in 1937 at the capital of the Hittite empire in central Anatolia in modern Turkey and dated to the 14th to 13th century BC.

5. Archeologically the Mt Ebal Lead Curse Tablet dates to the Late Bronze Age: 1406-1150 BC

a. The curse tablet was found in Zertal’s excavation dump of Joshua’s altar which he determined was abandoned around 1150 BC, dating the curse tablet earlier than 1150 BC.

|

b. Zertal discovered a scarab of Thutmoses III at Mt. Ebal in the earliest stratum II, but concluded the scarab was a ceremonial replica created during the reign of Ramses II who Zertal misidentified as the pharaoh of the exodus. Steven Rudd rejected the scarab was a replica in AD 2006, and redated Zertal’s stratum II from 1275 BC to 1446 BC, which is perfect synchronism for Thutmoses III as the Pharaoh of the exodus. It is expected that the Hebrews left Egypt in possession with his scarabs which they acquired during the 18 years he was their pharaoh before the exodus. |

“About 70 to 80 [circular] installations were uncovered to the north, south and east of the central complex. These consisted of crudely arranged stone-bordered circles, squares, or rectangles (and many irregular shapes) with an average diameter or width of 30 cm. to 70 cm. They are intermixed and built one upon the other in some cases. … Wall 17, which extends from the northern courtyard, and Wall 44, which joins curving Wall 22. This wall encompasses other installations, in one of which scarab No. 2 [Thutmoses III] was unearthed. The stratigraphical position of the scarab could not be fixed, because of the mixture of the Strata II and I installations, but its deep location hints at Stratum II.” (An Early Iron Age Cultic Site On Mount Ebal: Excavation Seasons 1982-1987 Preliminary Report, Adam Zertal, Tel Aviv, vol 14, p118, 1987 AD)

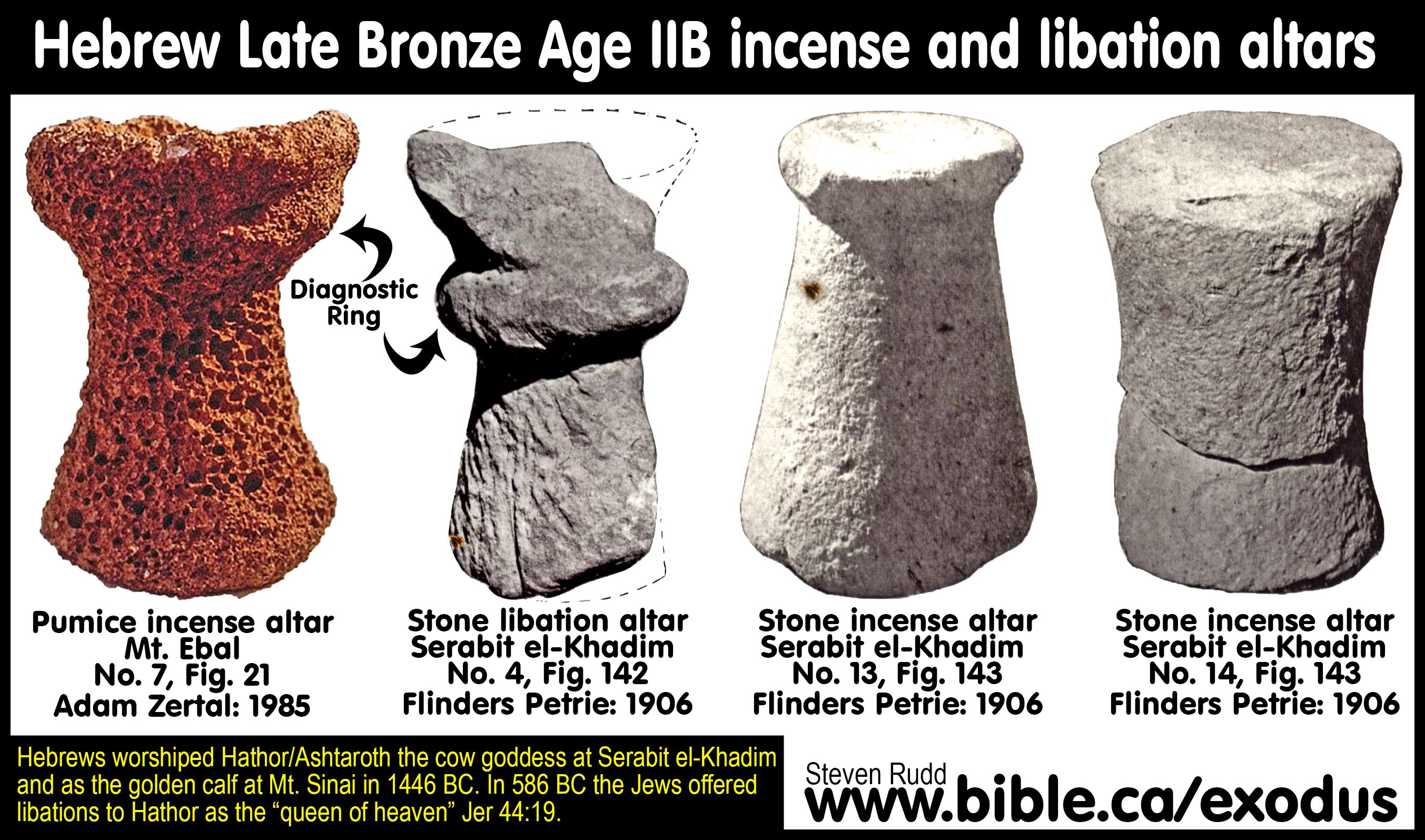

c. In AD 1985, Adam Zertal excavated an incense altar at Joshua’s altar in stratum II. In the AD 1906, Flinders Petrie excavated a similar sandstone incense and libation altars from the Hathor temple at Serabit el-Khadim which Petrie dated to the Late Bronze Age and identified as of Semitic (i.e. Hebrew) origin. Hebrews worshiped Hathor/Ashtaroth the cow goddess at Serabit el-Khadim and as the golden calf at Mt. Sinai in 1446 BC. In 586 BC the Jews offered libations to Hathor as the “queen of heaven” (Jer 44:19.) In AD 2016, Douglas Petrovich identified a series of Hebrew “Sinai Inscriptions” at Serabit el-Khadim that he dated to the time of the exodus. Although Zertal never tested the origin of the pumice, it may have been from the Thera eruption, which Manfred Bietak (excavator of Goshen at Tel el-Dab’a) dated to the time of Thutmoses III using low Egyptian chronology. To complete the circle of evidence, Zertal used Petrie’s sandstone chalice as a parallel for the Mt. Ebal chalice in his exaction report. “Pumice chalice. This vessel was placed in Pit 250 before the Stratum LB fill was poured and therefore dates to Stratum II. It is 10 cm. high and the diameter of the base - and upper bowl is 8.5 cm. The bowl is 3 cm. deep.” (Adam Zertal excavation report of Joshua’s altar, 1985 AD) During the exodus, Moses camped at Succoth on the Gulf of Suez, at a location which is directly adjacent the turquoise mines of Serabit el-Khadim to pick up the Hebrew slaves who worked there. In AD 2006, Steven Rudd redated Zertal’s stratum II from 1275 BC to 1406 BC because both the scarab of Thutmoses III and the pumice incense altar were excavated from stratum II.

“The plainest and roughest of the altars were nos. 14 and 15, which were found in the Portico; no. 15 has been merely rough-chipped, no. 14 has been dressed over. The altar no. 13 is well finished, and on the top the surface was burnt for about a quarter of an inch inwards, black outside and discoloured below. This proves that such altars were used for burning; and from the small size, about 5 to 7 inches across, the only substance burnt on them must have been inflammable, such as incense. This altar is a foot high; it was found in the shrine of Sopdu and is now in the British Museum. A larger and more elaborate Altar (no. 4) was found in the Sacred Cave. It has been much broken about the top, but it had originally a basin hollow about 9 inches wide and 4 inches deep which might perhaps have been for libations [liquid offerings]. Around the narrowest part is a thick roll 4½ inches high. The whole altar is 25 inches high. … Most of these altars seem to be intended for incense, and in one case there is the mark of burning on the top; they thus agree with what we know of the Jewish system, where a small altar was reserved specially for incense. We have here, then, another instance of Semitic worship, differing from that of Egypt, where incense was always offered on a shovel-shaped [stone] censer held in the hand.” (Researches in Sinai, Flinders Petrie, p133, 1906 AD)

6. Confirms scripture that Mt. Ebal was Mountain of curses: The curse tablet confirms that Mt. Ebal was the mountain of curses, which agrees with the Masoretic Text, the Samaritan Pentateuch, and the Septuagint.

7. Confirms the early Exodus date of 1446 BC: The tablet provides strong evidence that the early date of the exodus in 1446 BC is correct, and the late date of 1253 BC is wrong.

8. The “Documentary Hypothesis” of Bible skeptics refuted:

a. The lead tablet confirms that sophisticated writing skills using an alphabetic script existed at the time of Moses. The lead tablet dismantles and collapses the “Documentary Hypothesis” of Bible scoffers, who say that scribes wrote different portions of Pentateuch centuries apart and that the Pentateuch as we have it today, did not exist before 600 BC. The epigraphic skill of the lead curse tablet scribe was more than sufficient to write the entire Pentateuch, proving such writing skills existed at the time of Moses in the Late Bronze Age. “Documentary Hypothesis” advocates cannot now argue with a straight face that the ability to write scripture did not exist until the Persian or Hellenistic period. The author of the text was not only a scribe, but he was a theological leader. The curse table used both El and YWH together in the Late Bronze Age, contra the Documentary Hypothesis. It’s time for these skeptics to join the toddlers Sunday School class and learn the Bible in a true light of faith.

9. Sophisticated chiastic parallelism collapses the “Documentary Hypothesis”: The message reads the same, top to bottom and bottom to top. “Ciasm” is a Latin transliteration of the Greek chiasma (χιασμα) referring to the Greek letter Χ (chi). Chiasm is the repetition of the same elements in inverted order: a-b-b´-a´; or if a middle element is present: a-b-c-b´-a´. Chiastic arrangement, conceived graphically, resembles the letter Χ. Caism is used extensively throughout scripture (Eccl 1:12–2:26; 4:1–16; 5:8–6:9).

a. Examples of Caism are common scripture (many also in Psalms)

The King’s Experiment Ecclesiastes 1:12–2:26

A: Work Is an Evil Business, 1:12–15

B: Wisdom Brings Trouble, 1:16–18

C: Examining Pleasure, 2:1–11

B′: Testing Wisdom, 2:12–17

A′: Studying Toil, 2:18–23

Toil for Self and in Community Ecclesiastes 4:1–16

A: The Oppressed Abandoned, 4:1–3

B: Toil in Competition? Be Content! 4:4–6

C: Toil for No Purpose, 4:7–8

B′: Toil Alone? Work Together! 4:9–12

A′: The Oppressed Wise Youth Abandoned, 4:13–16

Enjoyment Instead of Greed Ecclesiastes 5:8–6:9

A: No Satisfaction in Wealth, 5:8–12

B: Wealth Is Easily Lost, 5:13–17

C: Best to Find Good in One’s Work, 5:18–20

B′: God Gives Wealth, But It Is Lost, 6:1–6

A′: Little Satisfaction in Toil, Pleasure, Wisdom, 6:7–9

b. Caism in the 2019 Lead Curse Tablet of Mt. Ebal:

A: Cursed, cursed, cursed.

B: Cursed by the God YHW.

C: You will die cursed.

C’: Cursed you will surely die.

B’: Cursed by YHW.

A’: Cursed, cursed, cursed.

II. Hittite Submission (Suzerainty) Covenants and the Deuteronomy covenant:

The 2019 Lead Curse Tablet of Mt Ebal synchronizes with both account of the Bible covenant renewal ceremony in Joshua 8, and contemporary Hittite covenant ceremonies. Hittite submission covenants (suzerainty treaties) are known from the 1600 – 1200 BC and often contained 8 standard sections or parts. However, the order varied greatly even with the same Hittite ruler. Many treaties omit some of the 8 parts and/or invert the order of the parts and the document often ended with the curses and blessings as the last part. Notably, the curses are always followed by the blessings as they are in Deuteronomy 27-28. That Moses wrote Deuteronomy in the exact form of a contemporary 8 part Hittite covenant is not surprising since he was educated for 40 years as crown prince of Egypt in all military, economic and political matters (Acts 7:22). It is certain, therefore, that Moses had read many of these common covenants and likely even composed them for newly conquered vassal states of Egypt. Deuteronomy represents a summing up of all the events from Egypt to the shores of the Jordan River into a formal legal document to bring the Hebrews into covenant with God. Since the literary structure of Deuteronomy and the curse tablet, exactly follow the form and content of these the many extant Hittite Suzerainty treaties, this provides strong evidence Deuteronomy was written before 1200 BC and not 600 BC. It is certain that the Hebrews were familiar with these 8 part Hittite covenants since Moses forbad the Hebrews from forming these covenants with foreign nations (Ex 23:32; Deut 7:2; Judges 2:2). Instead of forming submission covenants with the nations, the Hebrew were only permitted to form an 8 point covenant with God alone. It is not surprising that the book of Deuteronomy is organized into the known format of an 8 part covenant:

1. Preamble: Deut 1:1-5

a. Hittite covenants often began by introducing the law-giving King under whom vassals were required to submit backed by the authority of the gods.

b. In the Deuteronomy covenant, Moses is introduced as the supreme lawgiver and authority on earth on behalf of God, who delivers the “Law of Moses” to the people.

c. Preamble of the 10 commandments: Ex 20:1; Deut 5:1

2. Historical survey: Deut 1:6—4:43.

a. Generally following the “preamble”, Hittite covenants recounted the historical interaction between the king and his conquered vassals.

b. In the Deuteronomy covenant, the exodus and conquest were recounted before they crossed the Jordan.

c. Historical survey of the 10 commandments: Ex 20:2; Deut 5:2-5

3. Law: Deut 5—26.

a. As their central purpose, all Hittite covenants contained a set of laws that vassals were required to obey.

b. In the Deuteronomy covenant the Law of Moses included the Ten Commandments and the ordinances in the Book of the Law.

c. The law of the 10 commandments: Ex 20:3-17; Deut 5:6-21

4. Divine witness: Deut 4:26; 28:58; 30:19; 31:28; 32:1 + 31:19–21

a. Immediately preceding the oath of curses and blessings, Hittite covenants often contained a long list of pagan gods who “shall stand and listen to the oath and be witnesses” to the covenant.

i. “The Storm-god, Lord of Heaven and Earth, the Moon-god and the Sun-god, the Moon-god of Harran, heaven and earth, the Storm-god, Lord of the kurinnu of Kahat, the Deity of Herds of Kurta, the Storm-god, Lord of Uhushuman, Ea-sharri, Lord of Wisdom, Anu, Antu, Enlil, Ninlil, the Mitra-gods, the Varuna-gods, Indra, the Nasatya-gods, the underground watercourse(?), Shamanminuhi, the Storm-god, Lord of Washshukkanni, the Storm-god, Lord of the Temple Platform(?) of Irrite, Partahi of Shuta, Nabarbi, Shuruhi, Ishtar, Evening Star, Shala, Belet-ekalli, Damkina, Ishhara, the mountains and rivers, the deities of heaven, and the deities of earth. They shall stand and listen and be witnesses to these words of the treaty/covenant.” (Treaty covenant between Shattiwaza of Mittanni and Suppiluliuma I of Hatti: 1344–1322 BC, A rev. 54–58, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p52, 1999 AD)

b. In the Deuteronomy covenant, Moses identified the divine witness: “respect this honored and awesome name: YHWH your God”. In addition to YHWH being the central covenant maker in the Deuteronomy covenant, Moses also calls upon “Heaven and earth”, (all creation: men and angels) as a witness. Finally, God said the Song of Moses would be taught and remembered by Israel forever as a witness between the Hebrews and God.

c. The Divine witness of the 10 commandments: Ex 20:2a,18,22; Deut 5:6a,22

d. The 2019 Lead Curse Tablet of Mt Ebal as a legal text, twice named “El YHWH” as the God who witnessed the oath of curses.

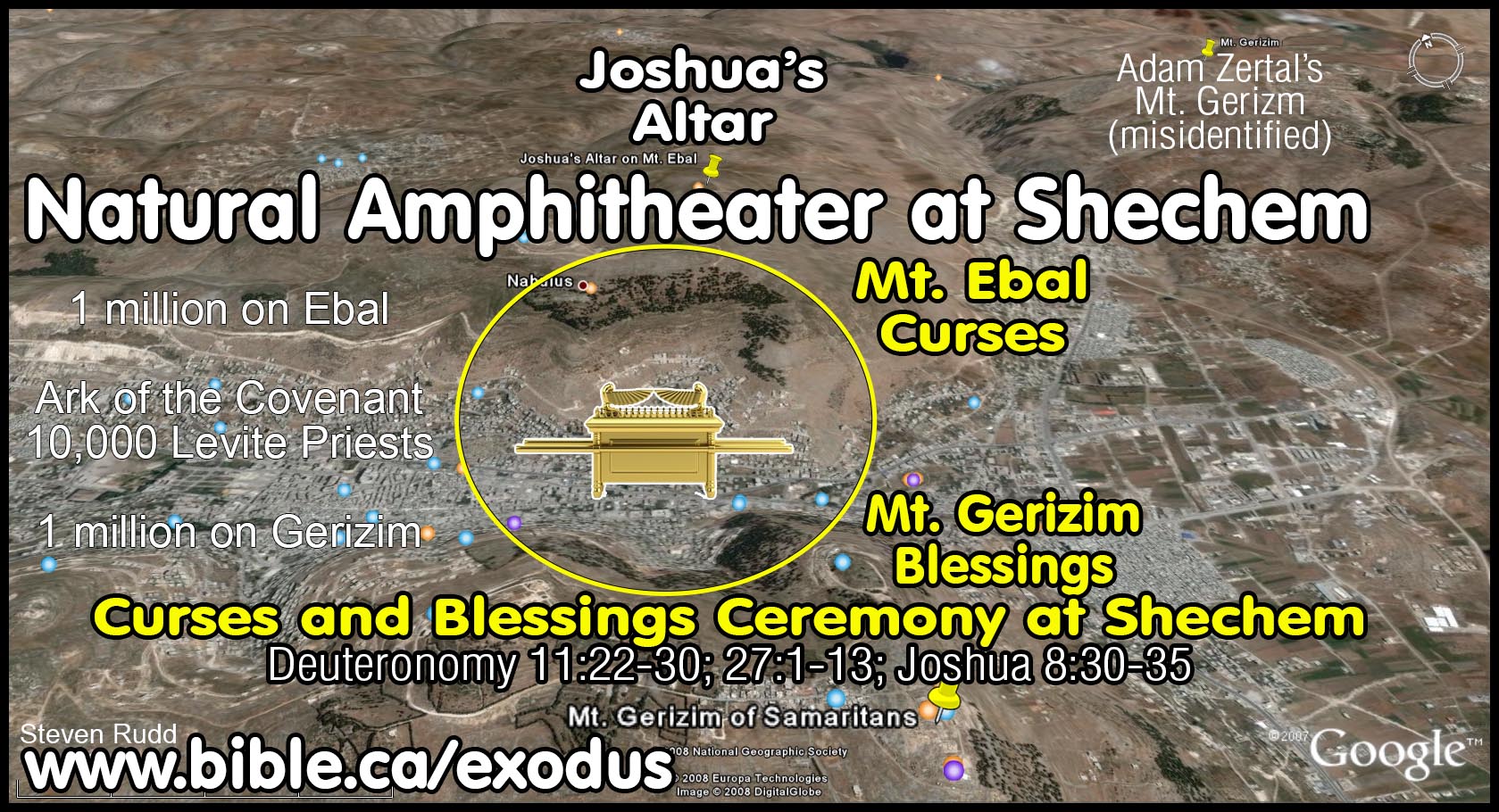

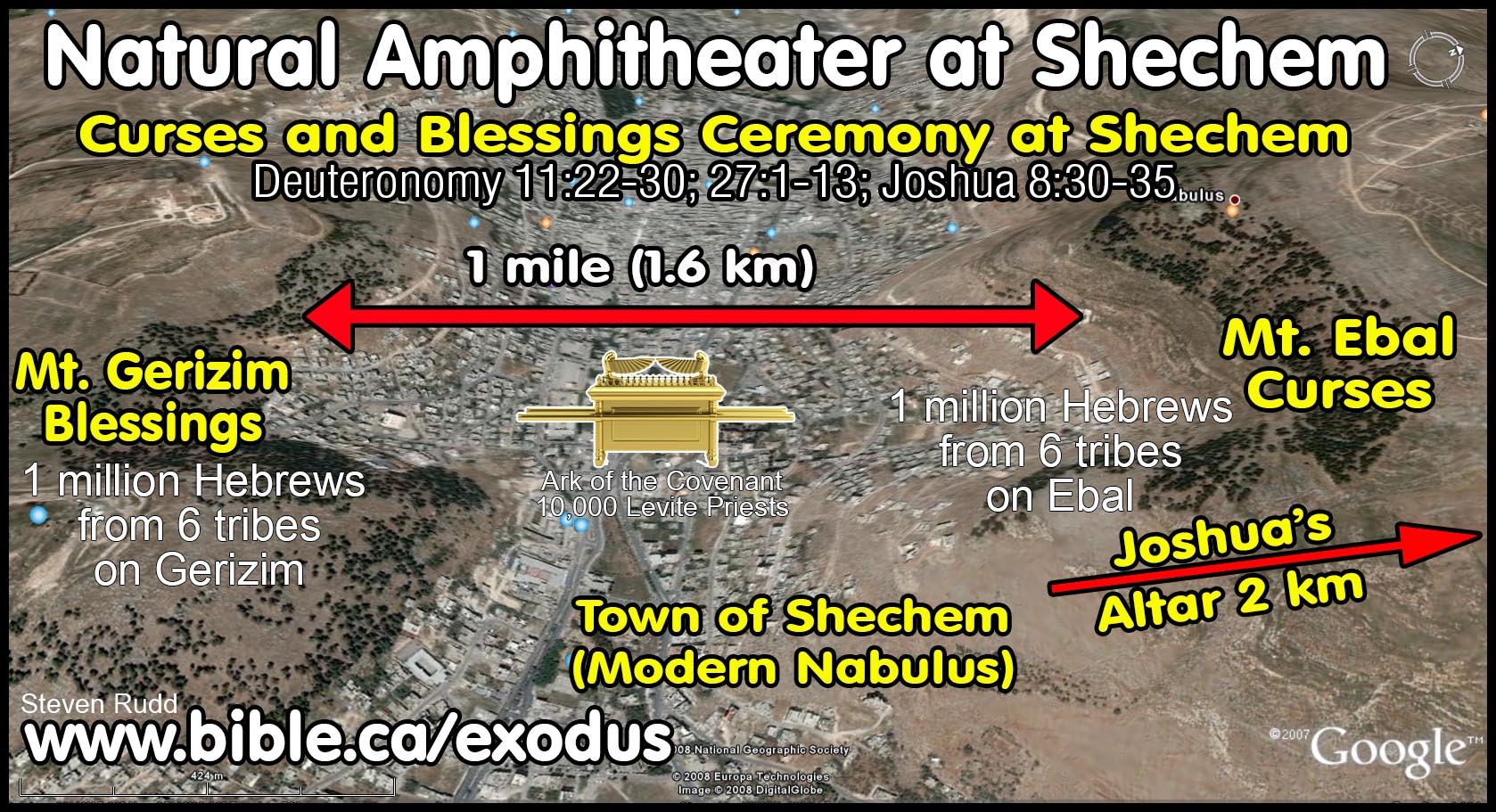

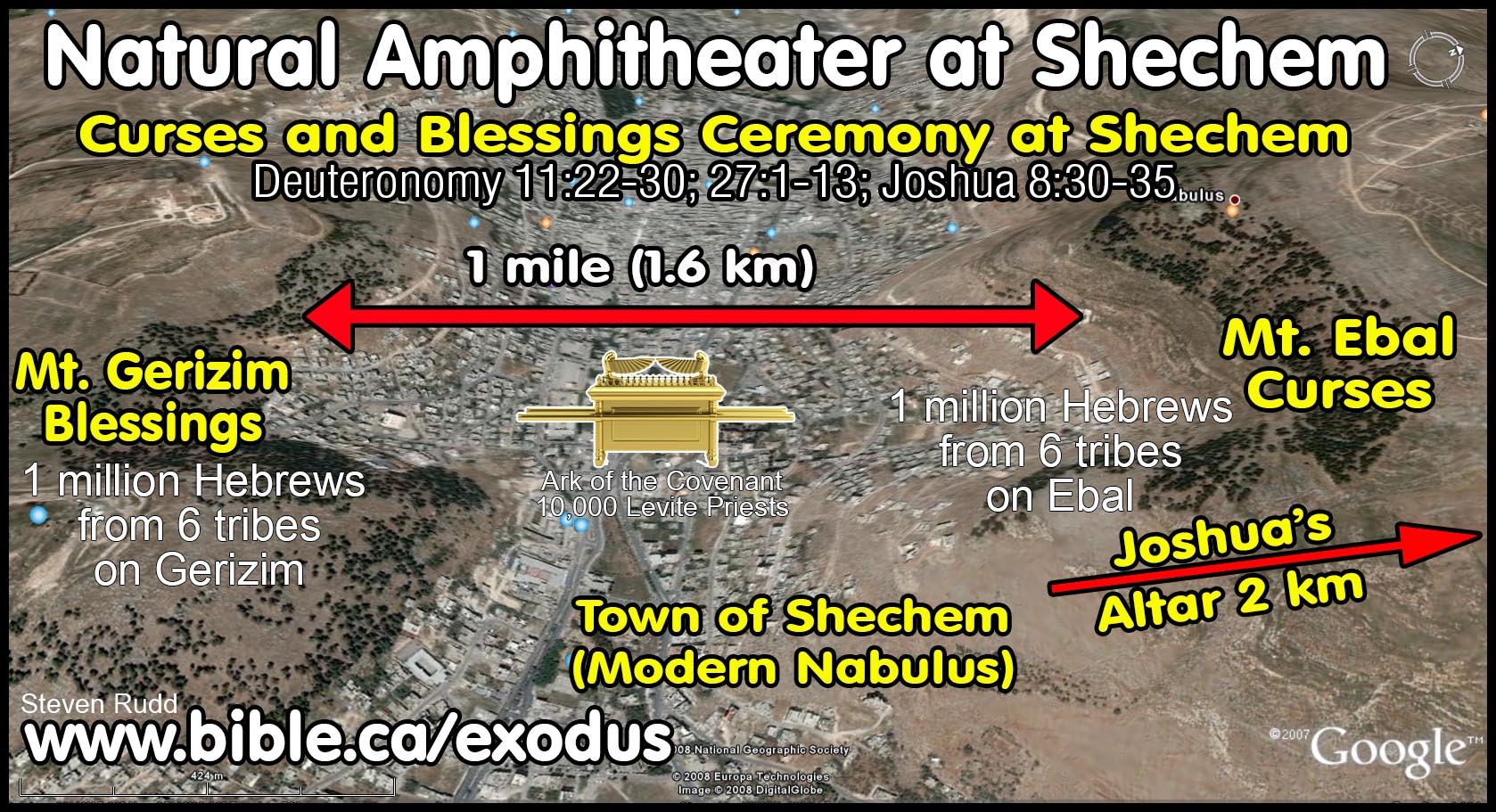

5. Curses and blessings ceremony: Deut 11:29; Chapters 27-30

a.

Both Hittite covenants and Deuteronomy covenants required individuals to

swear a self-imprecatory submission oath of curses and blessings, meaning, the

vassal condemned himself to death if he broke the covenant. If you kept the

law, you were blessed by the gods and if you broke the law the gods must curse

you according to the oath spoken from your own lips. There is a natural

acoustic amphitheater between Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim with a 1 km valley in

the middle. 1 million Hebrews from six tribes stood on the amphitheater slopes

of Mt. Gerizim for the curses, as did the other six tribes on Mt. Ebal for the

blessings. In the valley was the tabernacle tent with Moses and the priests.

The estimated 10,000 (Num 3:39) Levitical priests spoke in unison as one voice,

each of the twelve curses to the six tribes standing within the natural

amphitheater on Mt. Ebal and they replied “amen” after each. Then the remaining

six tribes standing within the natural amphitheater on Mt. Gerizim said “amen”

to the 12 blessings. There are many other examples of self-imprecatory curses

in scripture (Job 31:21–23; 1 Sam 25:22).

i. 1344–1322 BC: Treaty covenant between Suppiluliuma I of Hatti and Huqqana of Hayasa: This treaty had two sets of blessing and curses in the body and the end of the document. The first set were curse + blessings like Deuteronomy 27/28 and the document ended with second set (not included herein) in reverse order: blessings + curse. Curses: (A ii 1) “and if you do not tell me about him, but even [hide] him. (A ii 2–9) or go over to him, abandoning My Majesty—if you act thus, these oath deities will not leave you alone, nor on your account will they leave alone that man to whom you go over. They shall destroy him. And the oath gods shall not neglect this matter in regard to both of you, and they shall not make it permissible for both of you. They shall destroy both of you together and thereby fulfill the wishes of My Majesty.” Blessings: (A ii 10–13) “But if you, Huqqana, protect only My Majesty and take a stand only behind My Majesty, then these oath gods shall benevolently protect you, and you shall thrive in the hand of My Majesty.” (Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p29, 1999 AD)

ii. 1344–1322 BC: Treaty covenant between Suppiluliuma I of Hatti and Aziru of Amurru: Curses: (A rev. 12′–16′) “All the words of the treaty and of the oath which are written] on this tablet—if Aziru does not observe these words of the treaty and of the oath, but transgresses the oath, then these oath gods shall destroy Aziru, together with his person, his wives, his sons, his grandsons, his household, his city, his land, and his possessions.” Blessings: (A rev. 17′–20′) “But if Aziru observes these words of the treaty] and of the oath which are written on this tablet], then these oath gods shall protect Aziru, together with his person, his wives, his sons, his grand-sons, his household, his city, his land, and his possessions. [end of document]” (Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p36, 1999 AD)

iii. 1344–1322 BC: Treaty covenant between Shattiwaza of Mittanni and Suppiluliuma I of Hatti: Curses: (rev. 25–34) “If you, Shattiwaza, and you Hurrians do not observe the words of this treaty, these gods of the oath shall destroy you, Shattiwaza, and you Hurrians, together with your land, together with your wives, together with your sons, and together with your possessions. They will draw you out like malt from its husk. As one does not get a plant from … —if you, Shattiwaza,—so you together with any other wife whom you might take (in place of my daughter), and you Hurrians, together with their wives and their sons, shall thus have no progeny. And these gods, lords of the oath, shall allot you poverty and destitution. And they shall overthrow your throne, Shattiwaza. And you, Shattiwaza—these oath gods shall snap you off like a reed, together with your land. Your name and your progeny by another wife whom you might take shall be eradicated from [the earth]. And you, Shattiwaza, together with your land, because of not delivering goodness and recovery(?) among the Hurrians—you(!) shall be eradicated. The ground shall be ice, so that you will slip. The ground of your land shall be a marsh of … , so that you will certainly sink and be unable to cross. You, Shattiwaza, and you Hurrians shall be the enemies of the Thousand Gods. They shall defeat you.” Blessings: (rev. 35–39) “If you, Shattiwa, and you Hurrians observe this treaty and oath, these gods shall protect you, Shattiwaza, together with the daughter of the Great King of Hatti, her sons and grandsons, and you Hurrians, together with your wives and your sons, and together with your land. And the land of Mittanni shall return to its previous state. It shall prosper and expand. And you(!), Shattiwaza, your sons and grandsons by the daughter of the Great King, King of Hatti—they shall accept you(!) for kingship for eternity. Prolong the life of the throne of your father; prolong the life of the land of Mittanni.” (Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p52, 1999 AD)

iv. 1321-1295 BC: Treaty covenant between Mursili II of Hatti and Manapa-Tarhunta of the Land of the Seha River: Curses: (A iv 29′–39′) “And if you, Manapa-Tarhunta, together with the people of the land of the Seha River and the land of Appawiya, do not observe these words, and in the future, to the first and second generation, you turn away, or you alter these words of the tablet—whatever is contained on this tablet, then these oath gods shall eradicate you, together with your person, your wives, your sons, your grandsons, your household, [your land], your infantry, your horses, your chariots(?), and together with your possessions, from the Dark Earth.” Blessings: (A iv 40′–46′) “But if you, Manapa-Tarhunta, observe these words of the tablet, and in the future you do not turn away from the King of Hatti, together with my sons, and from the word of the oath, then these oath gods shall benevolently protect you. And your sons shall thrive in the hand of My Majesty.” (Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p86, 1999 AD)

b. Twelve curses and blessings of Mt. Ebal and Mt Gerizim in Deut 27-28: 1. Cursed/Blessed in the city and country. 2. Sterile/Fertile women. 3. Drought/Plentiful crops. 4. Sterile/Fertile livestock. 5. Famine/Abundant bread and grain. 6. Cursed/Blessed coming in and going out. 7. Defeated/Defeat enemies. 8. Ridiculed/Established as God's holy people. 9. Fear, mental illness, insanity, disease/Healthy, feared by other nations. 10. Powder & dust/Plentiful rain. 11. Borrow/Lend to other nations. 12. Tail/head to other nations.

c. The curses and blessings of the 10 commandments: Ex 20:5b,6,7b,12; Deut 5:9b,10,11,16,33. Oath: Deut 5:27

d. Since the 2019 Lead Curse Tablet of Mt Ebal was a legal text of a covenant, there must have been a corresponding set of blessings. Although unrelated, the Numbers 6:24 silver blessings scroll was found at Ketef Hinnom in AD 1980. There are 10 curses in the curse tablet but 12 curses in Deut 27. The “10” curses may symbolize universal completeness or echo the number of the 10 commandments.

e. Isaiah recited 10 woes again the Hebrews in Isa 3:9-10:1

f. Jesus recited 8 curses (woes) against the scribes and Pharisees, and 9 blessings (Mt 5; 23).

6. Succession: Deut 31—34

a. Hittite covenants required vassals and their descendants to continue to obey the succeeding sons of the Hittite kings. Succession clauses generally preceded the oath of curses and blessing, but in the Deuteronomy covenant the succession clauses came after the oath.

b. The Deuteronomy covenant had dual succession clauses where both Joshua and Moses were two different antitypes of Jesus. First, Joshua succeeded Moses as physical leader, but not a lawgiver (Deut 31:14-23; 34:9). Second, Jesus succeeded Moses as the messianic spiritual leader and lawgiver of the New Covenant (Deut 18:18; Acts 3:22; 7:37; Heb 8:6).

c. The succession of the 10 commandments (God to Moses): Ex 20:19; Deut 5:25-27

d. The Law of Moses was in force continually from 1446 BC until it was abolished by being nailed to the cross on 3 April AD 33, then it was replaced by the Law of Christ (Col 2:14; 1 Cor 9:21; Gal 6:2).

7. Depository of duplicate copies: Deut 10:2; 31:24–30

a. In Hittite covenants, the original copy was deposited in the Hittite sanctuary and a duplicate copy was deposited in the vassal’s sanctuary.

i. “A duplicate of this tablet is deposited before the Sun-goddess of Arinna, since the Sun-goddess of Arinna governs kingship and queenship. And in the land of Mittanni a duplicate is deposited before the Storm-god, Lord of the kurinnu of Kahat.” (Treaty covenant between Suppiluliuma I of Hatti and Shattiwaza of Mittanni: 1344–1322 BC, A rev. 35–53, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p52, 1999 AD)

b. In the Deuteronomy covenant the formal textual object of the “old covenant” was the ten commandments written by the finger of God on stone and placed in the Ark of Covenant where God dwelt, with access forbidden for all except the high priest (Deut 5:2-3; 9:9-11; Ex 34:27-28; 1 Ki 8:9+21). While the original “sealed copy” of the stone tablets covenant was in the Ark, a second papyrus “open copy” of the ten commandments was placed beside the Ark, which was brought outside the Tabernacle and made available for any Hebrew to read.

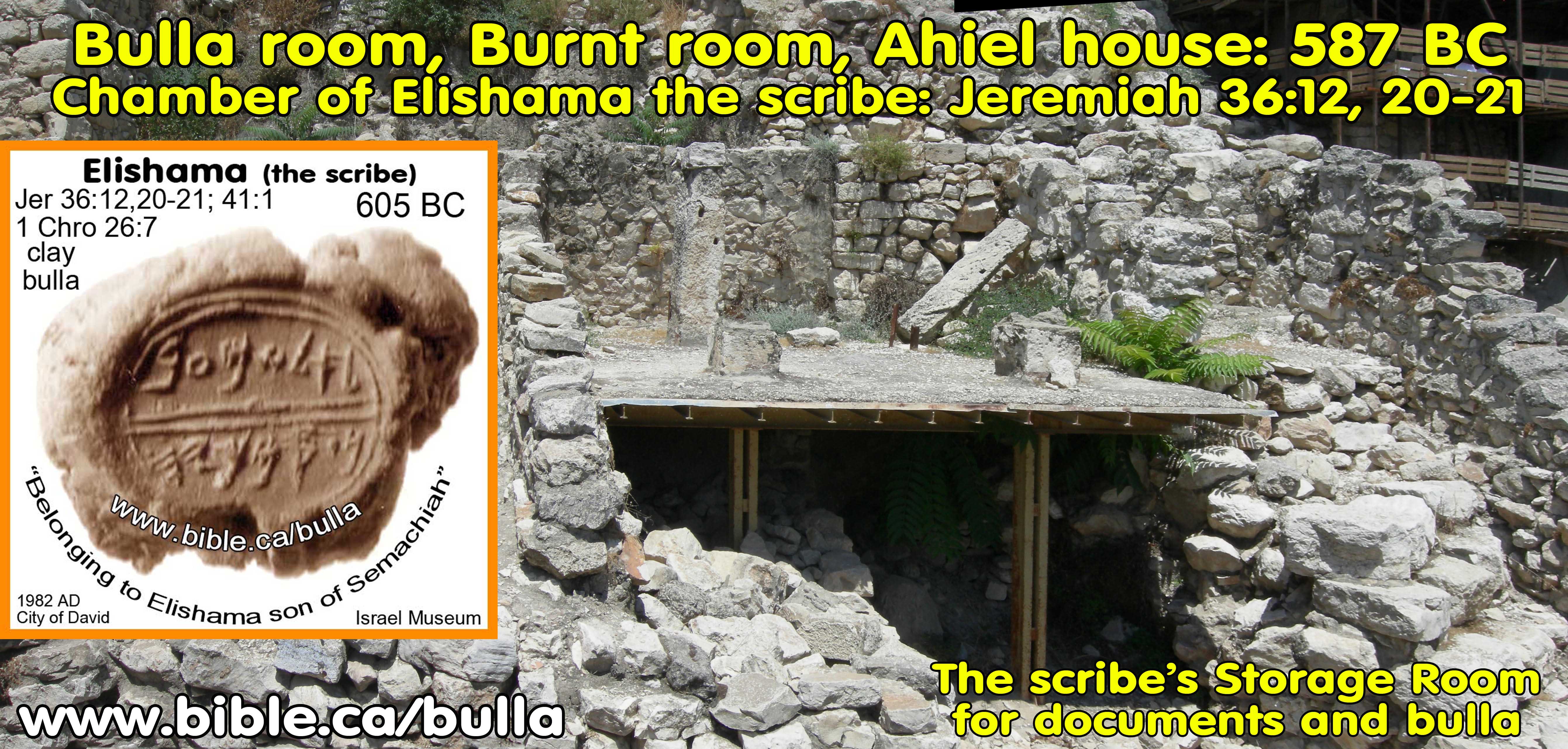

c.

This exactly mirrored how duplicate copies of Jeremiah’s “Deed of Land”

where deposited in the royal document chamber of Elishama the scribe in

Jerusalem (Jer 32:9-14). The “sealed copy” was inside the vault secured with

string and clay bulla seals, and the “open copy” was in the viewing room

adjacent to the vault for all to read. If a legal dispute occurred, and someone

challenged that the words of the open copy were different from the words of the

sealed copy inside the fault, they would call the officials who would open the

fault, break the seals of the original document, and compare it with the open

copy. In AD 1982, excavations in the City of David discovered both this official

document room of Elishama and his bulla (Jeremiah 36:20). What you read in the

book you find in the ground.

d. The depository of the 10 commandments: God gives tablets of stone to Moses: Deut 5:22

e. The 2019 Lead Curse Tablet of Mt Ebal was a sealed official legal document that was never intended to be opened. The lead tablet resembled an envelope with text on the outside and a folded sealed letter inside.

8. Public readings: Deut 6:7–9; 11:18-21; 17:18-20; 31:19-30

a. In Hittite covenants, the text was to be annually read to the vassal king and his people forever.

i. “It shall be read repeatedly, for ever and ever, before the king of the land of Mittanni and before the Hurrians.” (Treaty covenant between Suppiluliuma I of Hatti and Shattiwaza of Mittanni: 1344–1322 BC, A rev. 35–53, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Gary M. Beckman, Harry A. Hoffner, Vol 7, p52, 1999 AD)

b. In the Deuteronomy covenant, YHWH went one step further and required the king to write a copy of the law with his own hand and always keep it with him to read daily. The Hebrews had to write out the law on their doorposts, gates, hands, foreheads, and memorize the song of Moses. All this demonstrates the high literacy rate of the Hebrews where man, women and child could all read and write.

c. The public readings of the 10 commandments: Expectation that children will be taught: Ex 20:5; Deut 5:9;29

d. The 2019 Lead Curse Tablet of Mt Ebal demonstrates the exceptional literary skills at the time of Moses. It also proves that there was an alphabetic script with which Moses and Joshua could have written the earliest biblical books.

Conclusion: Only through Jesus can we escape the curse:

1. The Mt. Ebal Lead Curse Tablet reveals the nature of God and our chose of curse or blessings!

2. Serpent was cursed. Sinners are cursed. Hell is the final curse.

3. Joshua’s Altar was on mountain of curses where atonement was needed. Expiated from the curse comes through the blood of Christ. Become a Christian to escape the final curse.

|

"Christ redeemed us from the curse of the Law, having become a curse for us—for it is written, “Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree”— in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we would receive the promise of the Spirit through faith." (Galatians 3:13–14) |

By Steve Rudd, March 2022: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

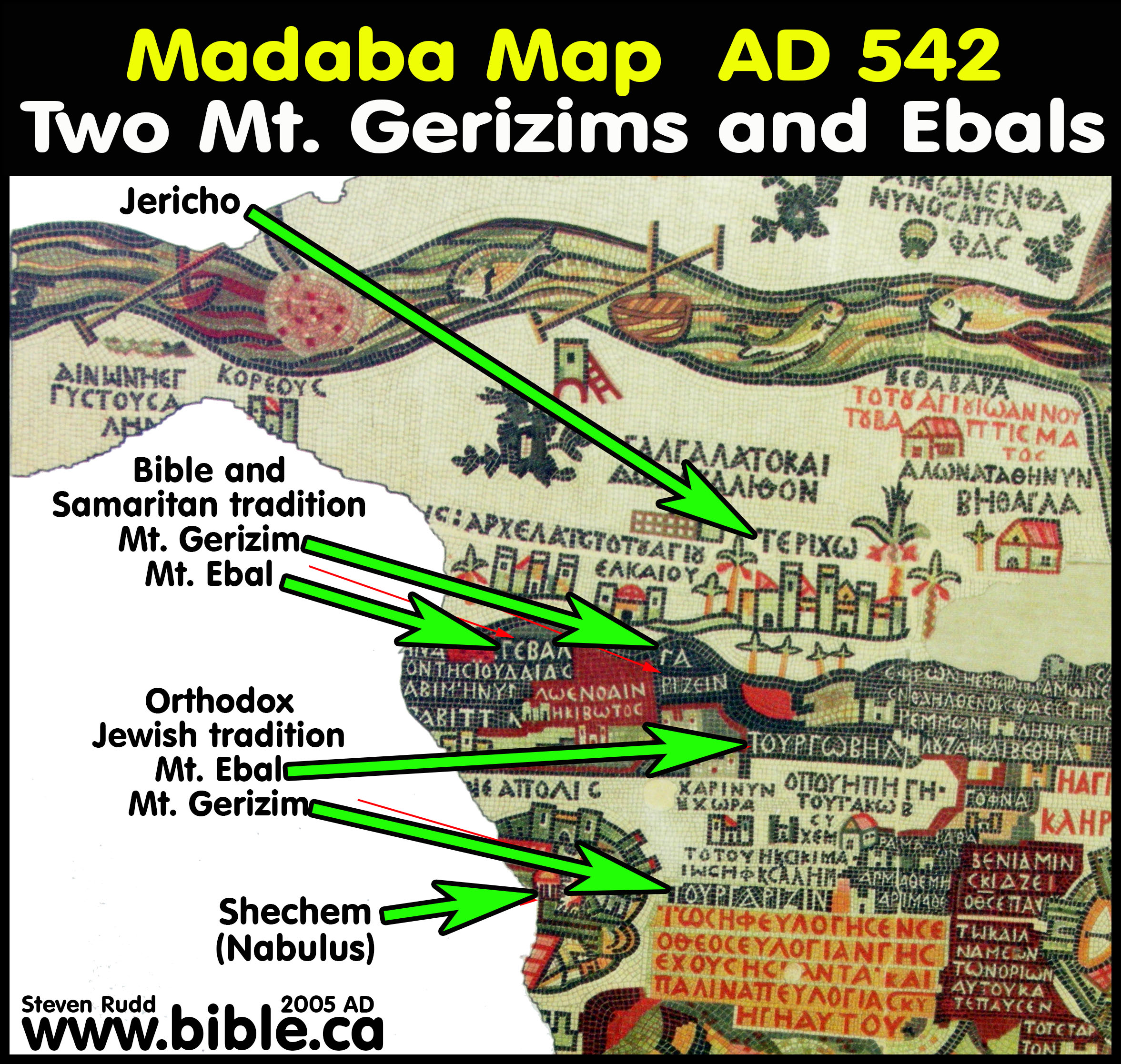

C. The history of Shechem, Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim:

- Today, ancient Shechem is located Tel Balata, which is about 3 km east of modern Nabulus. It may be that Tel Balata which literally means "a paving stone or tile" may in fact derive from Arabic balut, meaning "oak".

- In 2085 BC Abraham

left Haran at age 75 and the same year God appeared to him at Shechem: Gen

12:4. In 2085 BC, Abraham built an altar in Shechem beside the Oak of Moreh where God appeared to him and

promised to give his seed the land: "Abram passed through the land as

far as the site of Shechem, to the oak of Moreh.

Now the Canaanite was then in the land. The Lord appeared to Abram

and said, "To your descendants I will give this land." So he built an altar there to the Lord who had appeared

to him." Genesis 12:6-7. Regarding the "Oaks

of Moreh": Not just a single oak tree but a forest called the

"oaks of Moreh" were located

near, but not in Shechem, (Genesis 35:4) and apparently not directly on

either of the two mountains: "Are they [Mount Gerizim & Ebal] not

across the Jordan, west of the way toward the sunset, in the land of the

Canaanites who live in the Arabah, opposite Gilgal, beside the oaks of Moreh?" Deuteronomy

11:29-30. The location of the oaks of Moreh are clearly outside the formal

city limits of Shechem: "Then Hamor the father of Shechem went out to Jacob to speak with him." Genesis

34:6

- In 1900 BC, Jacob after he had fled from Laban back to Canaan, he built an altar at the place he camped "before the city of Shechem", not in Shechem. He bought this land: "Now Jacob came safely to the city of Shechem, which is in the land of Canaan, when he came from Paddan-aram, and camped before the city. He bought the piece of land where he had pitched his tent from the hand of the sons of Hamor, Shechem's father, for one hundred pieces of money. Then he erected there an altar and called it El-Elohe-Israel." Genesis 33:18-20

- In 1900 BC, just before Jacob moved from Shechem to Bethel, he hid the idols of his family under the "oak of Moreh" which was the very spot where Abraham had built an altar: "So they gave to Jacob all the foreign gods which they had and the rings which were in their ears, and Jacob hid them under the oak which was near Shechem." Genesis 35:4

- In 1883 BC, Joseph was sold into slavery. Jacob sent Joseph to Shechem to find his brothers, who had moved on to Dothan, where they betrayed him: "Israel said to Joseph, "Are not your brothers pasturing the flock in Shechem? Come, and I will send you to them." And he said to him, "I will go."" Genesis 37:13

- Joshua lived 1460 - 1350 BC: Joshua is described as a young man, a youth and was about 20 years old when Israel left Egypt in 1446 BC: (Ex 33:11; Num 11:28). Joseph was called "a youth" at age 17: Genesis 37:2. Joshua was chosen by Moses to fight Amalek at (Exodus 17:9) Rephidim. It is truly remarkable that a 20 year old was given the responsibility of leading the armies of Moses. Since the exodus was 1446 BC and Joshua lived to be 110 years old. (Joshua 24:29) This means Joshua was born about 1460 BC and died 1350 BC. This means that Joshua began serving Moses at age 20, and served Moses for 40 years in the wilderness and then 50 years in Canaan after crossing the Jordan.

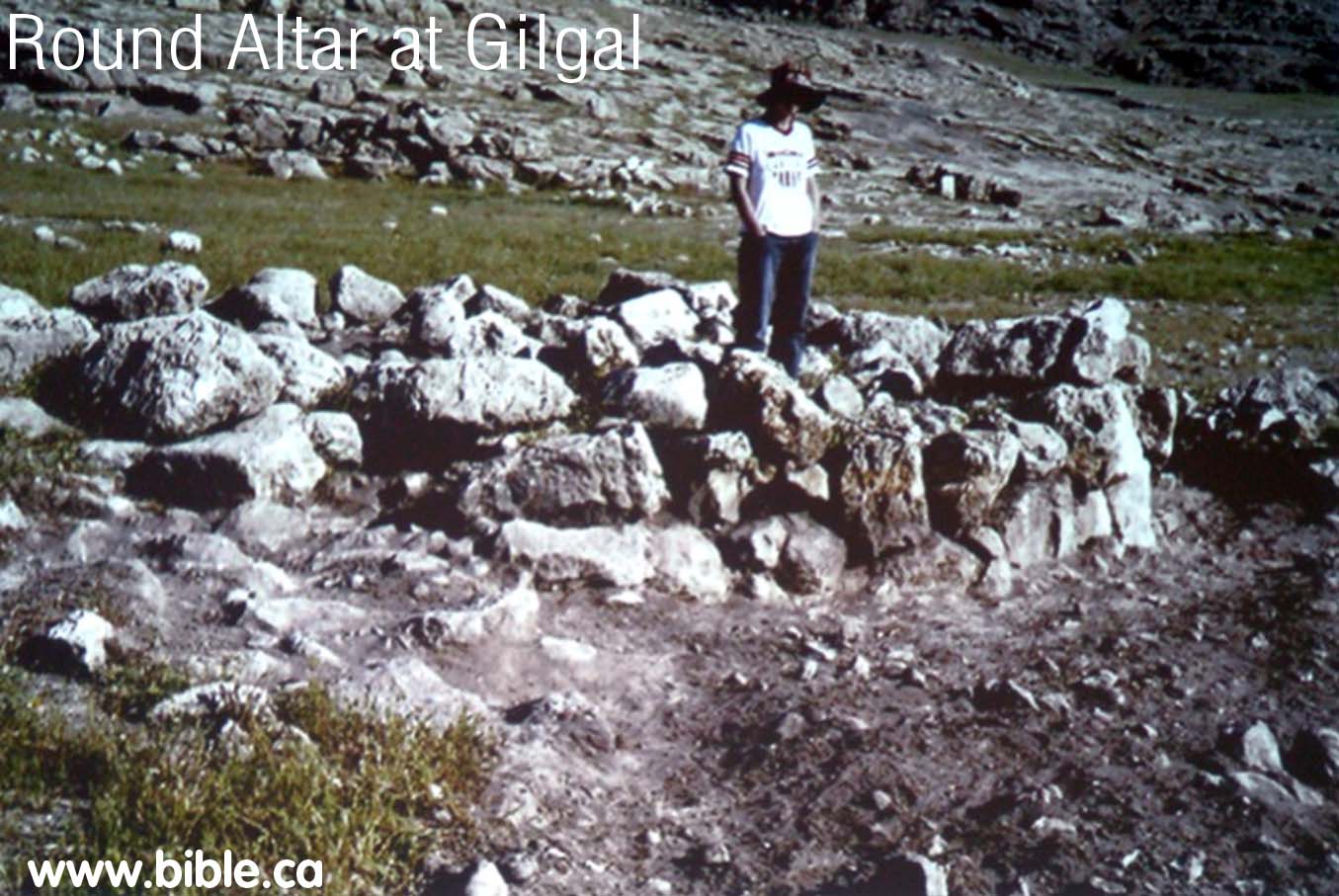

- In 1406, when Israel crossed the Jordan, the tabernacle was first set in the Gilgal (Josh 4:19).

- In 1390 BC, Joshua traveled from Gilgal, where the tabernacle was located, to Mt. Ebal beside Shechem to built the "altar of Joshua". The ark of the covenant was taken to Mt. Ebal and used in the blessings and curses ceremony, while the tabernacle remained at Gilgal. Josh 8:30

- In 1385 BC, the tabernacle then moved to Shiloh (Josh 18:1,10) where he divided up the land by lot (Joshua 19:51). Shiloh was the central gathering point for Israel at the time of Joshua: "When the sons of Israel heard of it, the whole congregation of the sons of Israel gathered themselves at Shiloh to go up against them in war." Joshua 22:12.

- In 110 AD, Josephus says that the tabernacle was first at Gilgal, then Shiloh after which Joshua built the Altar on Mt. Ebal. The correct order was Gilgal, Ebal, Shiloh: "The fifth year was not past, and there was not one of the Canaanites remained any longer, excepting some that had retired to places of great strength. So Joshua removed his camp to the mountainous country, and placed the tabernacle in the city of Shiloh, for that seemed a fit place for it, because of the beauty of its situation, until such time as their affairs would permit them to build a temple; and from thence he went to Shechem, together with all the people, and raised an altar where Moses had beforehand directed; then did he divide the army, and place one half of them on Mount Gerizim, and the other half on Mount Ebal, on which mountain the altar was; he also placed there the tribe of Levi, and the priests. (And when they had sacrificed, and denounced the [blessings and the] curses, and had left them engraved upon the altar, they returned to Shiloh. (Josephus, Antiquities 5.1.19, 68-70)

- In 1385, Shechem became a central "city of refuge" for Ephraim and Manasseh: "They gave them Shechem, the city of refuge for the manslayer, with its pasture lands, in the hill country of Ephraim, and Gezer with its pasture lands," Joshua 21:21 (Josh 20:2,7; 1 Chronicles 6:67)

- In 1380, From Shiloh, Joshua sent the tribe of Reuben transjordan for their inheritance: Joshua 22:9. The sons of Reuben built an exact replica of the altar of burnt offering in the tabernacle at Shiloh on the east side of the Jordan which created a huge problem. Altars had to be endorsed directly by God or else they were considered apostate and rebellious: "Thus says the whole congregation of the Lord, 'What is this unfaithful act which you have committed against the God of Israel, turning away from following the Lord this day, by building yourselves an altar, to rebel against the Lord this day?" Joshua 22:16 "Therefore we said, 'It shall also come about if they say this to us or to our generations in time to come, then we shall say, "See the copy of the altar of the Lord which our fathers made, not for burnt offering or for sacrifice; rather it is a witness between us and you." '" Joshua 22:28

- In 1360 BC Just before Joshua died, the tabernacle "sanctuary of the Lord" was moved from Shiloh to Shechem and placed near the Oaks of Moreh. Joshua gathered all the people there for his farewell address: "Then Joshua gathered all the tribes of Israel to Shechem, ... and they presented themselves before God." (Joshua 24:1). He also set up a memorial stone directly underneath the very oak that Abraham had built an altar near and Jacob had hid his family idols underneath: "So Joshua made a covenant with the people that day, and made for them a statute and an ordinance in Shechem. And Joshua wrote these words in the book of the law of God; and he took a large stone and set it up there under the oak [of Moreh] that was by the sanctuary of the Lord. Joshua said to all the people, "Behold, this stone shall be for a witness against us, for it has heard all the words of the Lord which He spoke to us; thus it shall be for a witness against you, so that you do not deny your God." Then Joshua dismissed the people, each to his inheritance." Joshua 24:25-28

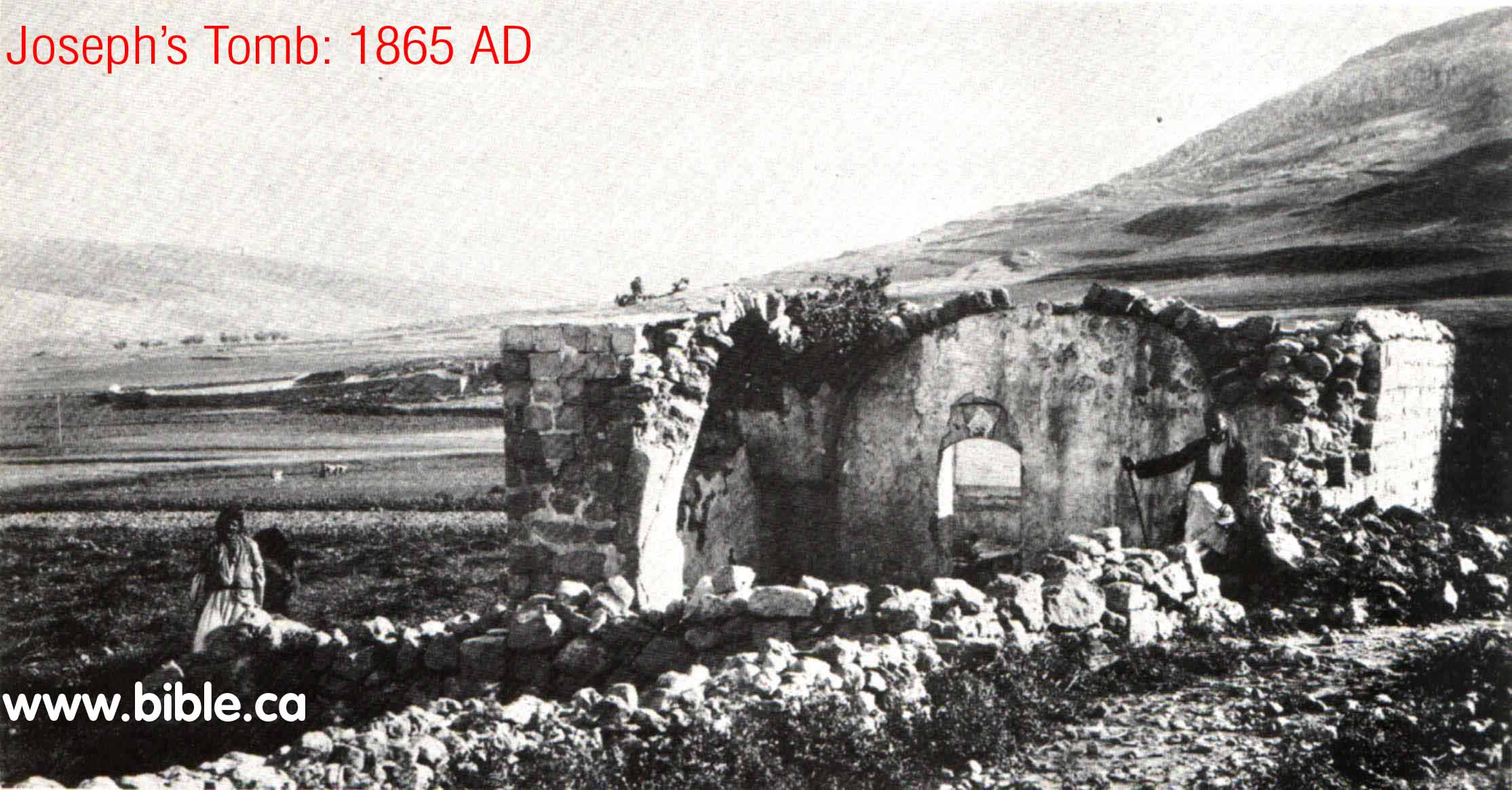

- In 1360 BC, Joshua died and was buried at Timnath-serah: Josh 24:30. At the same time Joseph, who had died in Egypt 440 years earlier (1800 BC), was buried at Shechem in a plot of land Jacob had bought 540 years earlier (1900 BC): "Now they buried the bones of Joseph, which the sons of Israel brought up from Egypt, at Shechem, in the piece of ground which Jacob had bought from the sons of Hamor the father of Shechem for one hundred pieces of money; and they became the inheritance of Joseph's sons." Joshua 24:32; Genesis 33:18-20; Acts 7:16.

- Today, the tomb of Joseph is located east

of modern Nabulus between Tel Balata and Sychar: "one of the tombs

whose location is known with the utmost degree of certainty and is based

on continuous documentation since biblical times. (Zvi Ilan, Tombs of the

Righteous in the Land of Israel, p. 365)

.

.

- On 7 October 2000, Joseph's Tomb, the

third most holy place in Judaism, was destroyed by Muslims. It is located

east of modern Nabulus between Shechem (Tel Balata) and Sychar at the foot

of Mt. Ebal. It had come under attack and the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF)

withdrew after gaining reassurances from the Palestinian Authority (PA)

that they would protect the site in accordance with their obligations

under the Oslo Accords to protect holy sites. Two hours after the

withdrawal Muslims began destroying the site. It was burned and torn down

stone by stone, then bulldozed. It was immediately declared a Muslim holy

site.

D. The ceremony in Shechem, Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim.

Scientists have tested this natural amphitheater many times and it works very well. This proves the ceremony of Joshua 8 could have really happened here.

Deut 11:22-30; 27:1-13; Joshua 8:30-35

- There was an elaborate and unique ceremony that took place at Shechem. It must have been an absolutely spectacular thing to be part of.

- In 110 AD, Josephus says recounts the ceremony: "from there he went to Shechem, together with all the people, and raised an altar where Moses had beforehand directed; then did he divide the army, and place one half of them on Mount Gerizim, and the other half on Mount Ebal, on which mountain the altar was; he also placed there the tribe of Levi, and the priests. (And when they had sacrificed, and denounced the [blessings and the] curses, and had left them engraved upon the altar, they returned to Shiloh. (Josephus, Antiquities 5.1.19, 68-70)

- It is clear that the ark of the covenant was located in the valley between Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim. Joshua stood beside the ark. The elders, priests and leaders of the people divided up into two groups and stood directly beside each side of the ark. The 2.5 million people then divided up into two groups: 7 of the tribes on the slopes of Mt. Gerizim and the other 6 tribes on the slopes of Mt. Ebal. Remember that Levi was not one of the twelve tribes and Joseph was represented by two tribes.

- There were 22,000 Levites: Numbers 3:39 who spoke the curses and blessings were read by all the Levite priests to the people. This would make it easy to hear on each mountain as each of the corresponding blessings and curses were read. 22,000 men can create quite a volume.

- The Census of Numbers 26, at just before crossing the Jordan: 601,730 of men over the age of 20. This number did not include Levi who was not enumerated. Curses on Mt. Ebal: Reuben + Gad + Asher + Zebulun + Dan + Naphtali = 307,930. Blessings on Mt. Gerizim: Simeon + Levi + Judah + Issachar + Joseph (Ephraim + Manasseh) + Benjamin = 293,800. But Levi was not enumerated in the census. The difference in numbers between the two sides was 14,130 and when we add in the women and children from Levi, that brings it up about equal. We know from Numbers 3:39 that there were 22,000 male Levites aged 20 and older. But many of these would likely be included in the actual pronouncements of the blessings and curses. So in the end, the numbers on each of the two mountains was pretty close to an equal split of about 1.25 million on each side for a total of 2.5 Million. Today, this many people easily fit into areas much smaller than the space Israel had on the two mountain tope, sides and valleys in front of the ark.

- When the priests read the curses to the people sitting on Mt. Ebal, the people sitting on Mt. Ebal would reply "Amen" after each curse was pronounced. The same was repeated for the blessings to the people sitting on Mt. Gerizim. "The Levites shall then answer and say to all the men of Israel with a loud voice, 'Cursed is the man who makes an idol or a molten image, an abomination to the Lord, the work of the hands of the craftsman, and sets it up in secret.' And all the people shall answer and say, 'Amen.'" Deuteronomy 27:14-15

- Joshua was to do a burnt offering sacrifice of an animal at the altar. It is not clear when this offering was made in respect to the timing of the ceremony. It could be that the offering was made before, during or after the blessings and curses were pronounce.

- The altar appears to be a one time use structure never intending to replace or compete with the altar of burnt offerings of the Tabernacle.

- The town of Shechem is a natural

amphitheater which has been tested several times to see if the ceremony of

Joshua 8 is possible. Each test proved the ceremony was easily possible,

especially if 22,000 priests are shouting and one million people are

replying!

- The location of the altar was about 3 km north of where the ark was located. There is no reason why the altar had to be located within view of the people.

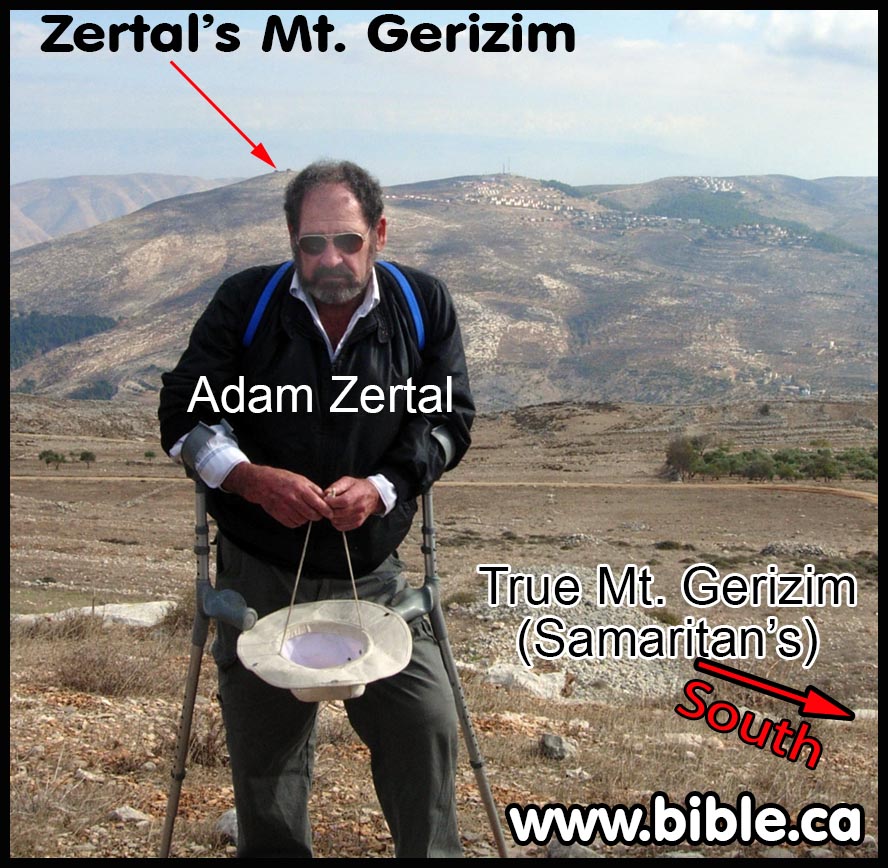

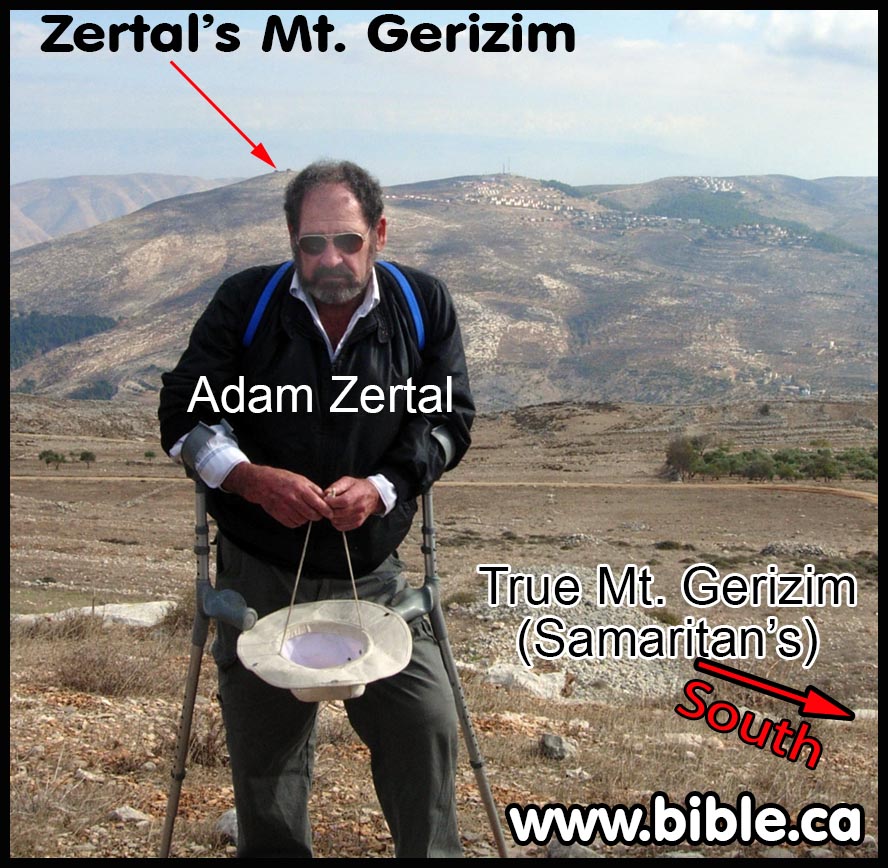

- The location of Joshua's altar that Adam Zertal discovered in 1980 doesn't disqualify the traditional Mt. Gerizim from being the correct location for that mountain. Zertal mistakenly thinks the location of the altar proves the Samaritans chose the wrong mountain in 500 BC as Mt. Gerizim. Zertal has chosen a new different mountain for Mt. Gerizim because of this. (see below) We disagree with Zertal and accept the Samaritan location for Mt. Gerizim.

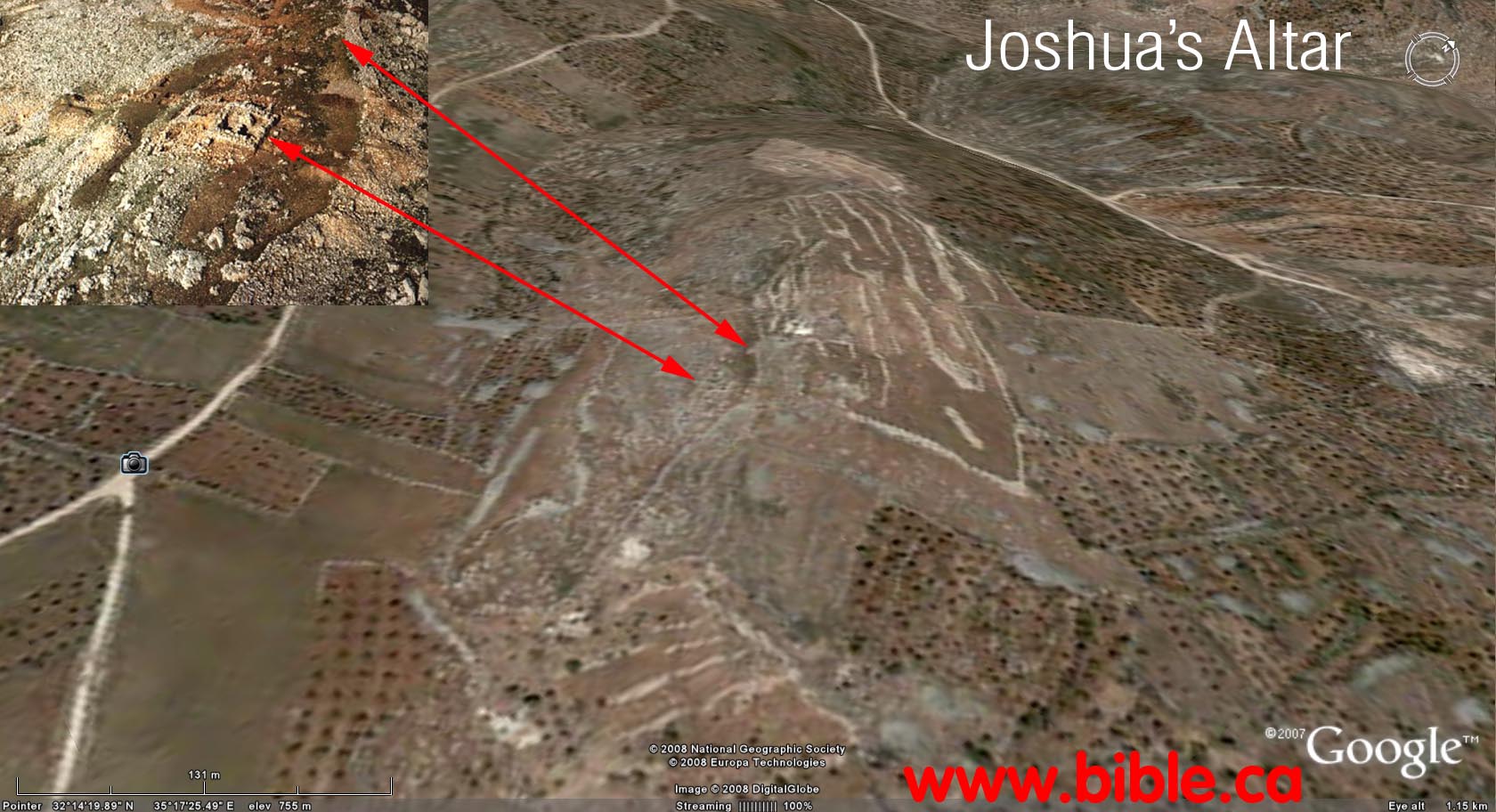

E. The location of Joshua's Altar on Ebal:

- Here is what the mound of rocks looked

like before excavation. "The excavators were surprised to find that the site had been deliberately buried under a layer of

stones before it was abandoned, presumably to prevent its

desecration. Perhaps abandoning Mt. `Ebal was related to establishing a

sacred site at Shiloh and the focus of the Israelite population shifting

from the territory of Manasseh in the north to that of Ephraim in the

central part of the country." (Adam Zertal)

- Ancient Shechem (Modern Nabulus) is

located between Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim.

- Here is an aerial view of Joshua's Altar

site:

- A close up view of the site with an

aerial photo inset

F. The rectangular Hebrew altar of 1250 BC:

- If you visit the site today, this is what

the altar looks like. This altar was built in 1250 BC and is a Hebrew

altar.

- Here is the site early on in the

excavation:

"A ramp of unhewn stones, 4 feet wide by 23 feet long, rises to the top of the platform from the southwest. The gentle incline, easily climbed and the presence of the ramp itself accord with the explicit scriptural injunction: "Neither shalt thou go up by steps unto Mine altar, that thy nakedness be not uncovered thereon" (Exodus 20:26)." (Adam Zertal) - The four corners of the altar point to the four corners of the compass instead of the usual Hebrew custom of the sides facing to the compass. "Yet another detail of our altar suggests its Mesopotarnian roots. The four corners of our altar point north, south, east and west. In Mesopotamia, all sacred structures were oriented so that each corner was directed to a point on the compass. By contrast, the Second Temple was oriented so that its sides, not its corners, faced the four directions of the compass. The Temple altar had this same orientation." (Adam Zertal) "It is interesting that the corners of the platform point due north, south, east and west. The practice of constructing sacred buildings so that their corners pointed in the directions of the compass was characteristic of Mesopotamia throughout its history. Temples, as well as altars, were always oriented in this way. The practice stems from the nature of the religion which developed in Babylonia and Assyria, based on four principal natural forces: earth, fire, air and water." (Adam Zertal)

- This must be an altar, it cannot be a house or a watchtower: "Our initial thought was that this was a farmhouse or perhaps a watchtower. But it was different in almost every respect from the farmhouse's watchtowers we know from examples all over the country. When we reached the bottom of the structure, we immediately noticed that there was neither a floor nor an entrance. The walls were laid directly upon bedrock. Obviously, we were not dealing with a building that had been regularly lived in. To explain the structure as a watchtower is even less satisfactory, because there is no reason for a watchtower to be here. Mt. Ebal has always been an obstacle to transportation. All transportation routes have avoided it. There is, thus, no road for a watchtower to observe. And there were no Iron Age settlements nearby." (Adam Zertal)

- This is a drawing of the site discovered

in 1980 by Zertal:

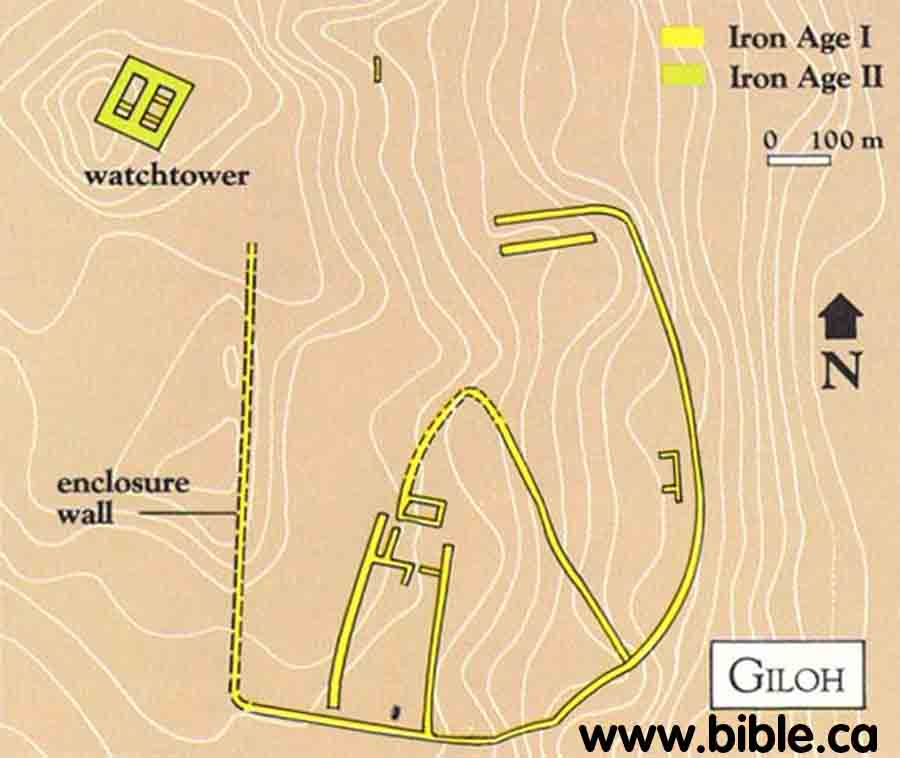

- Kempinski, who is a Bible trasher, has

suggested that the 1250 BC altar at Mt. Ebal is exactly like the

installations at Giloh. Superficially there appear to be similarities, but

Kempinski has been soundly refuted in this regard and it is generally agreed

that Mt. Ebal is not a watchtower. "According to Aharon Kempinski,

this plan of Giloh, an Iron Age site near Jerusalem, shows a square

structure, top, left, similar in shape and details to the Mt. Ebal

structure that Adam Zertal identifies as an altar. The plan has been drawn

by Amihai Mazar, the excavator of Giloh. Mazar identifies this building as

a watchtower, built in Iron Age II (1000-586 B.C.) and reused in the

Middle Ages. Mazar's plan shows a wall built around the Iron Age

settlement that, according to Kempinski, closely resembles Zertal's

temenos wall at Mt. Ebal." (Joshua's Altar—An Iron Age I Watchtower,

Aharon Kempinski, 1986, BAR)