Introduction to the History of Psychiatry:

|

For a brief summary of all the historical documents in this section on psychiatric history. |

||

|

|

||

Introduction to the History of Psychiatry:

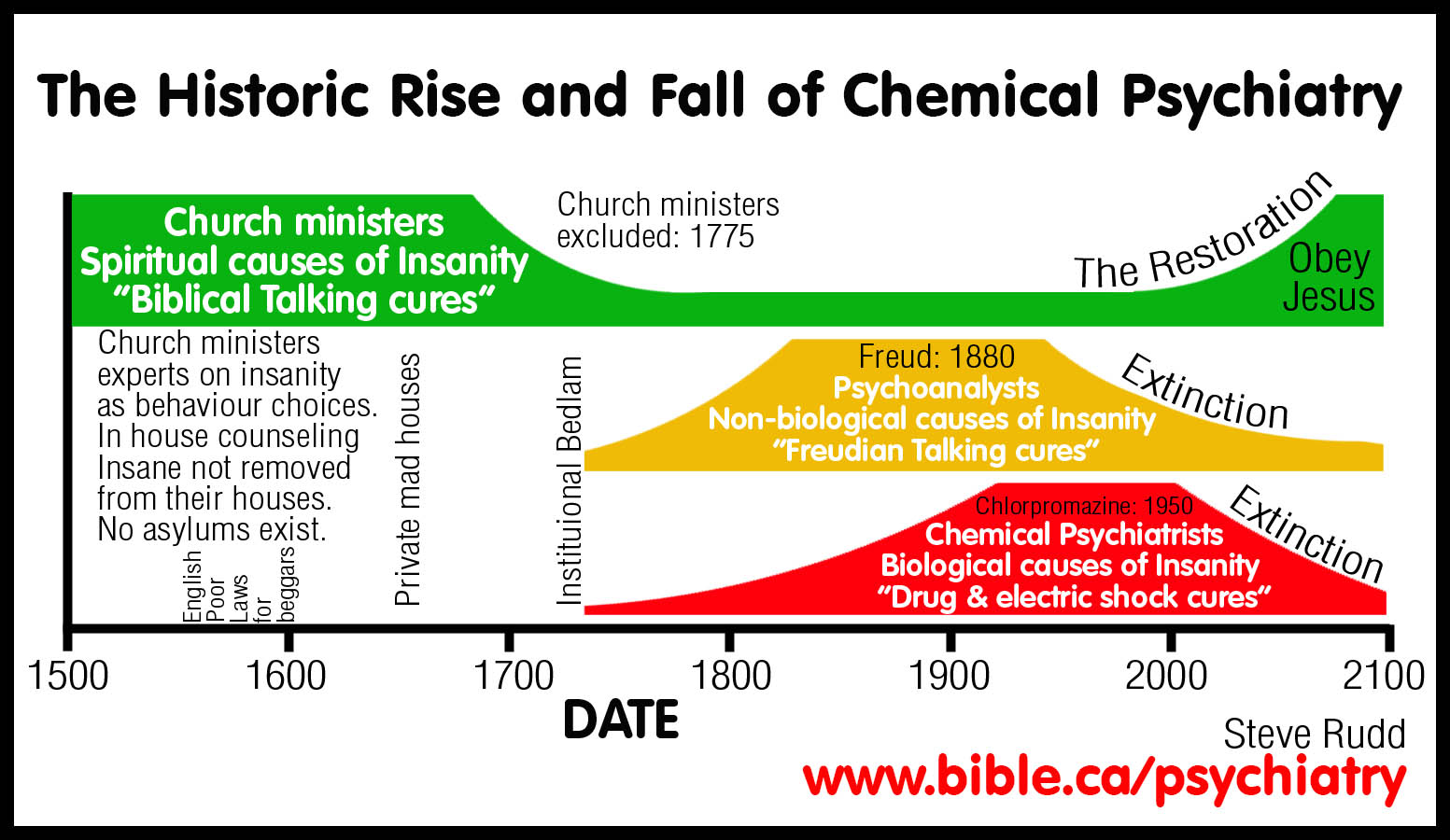

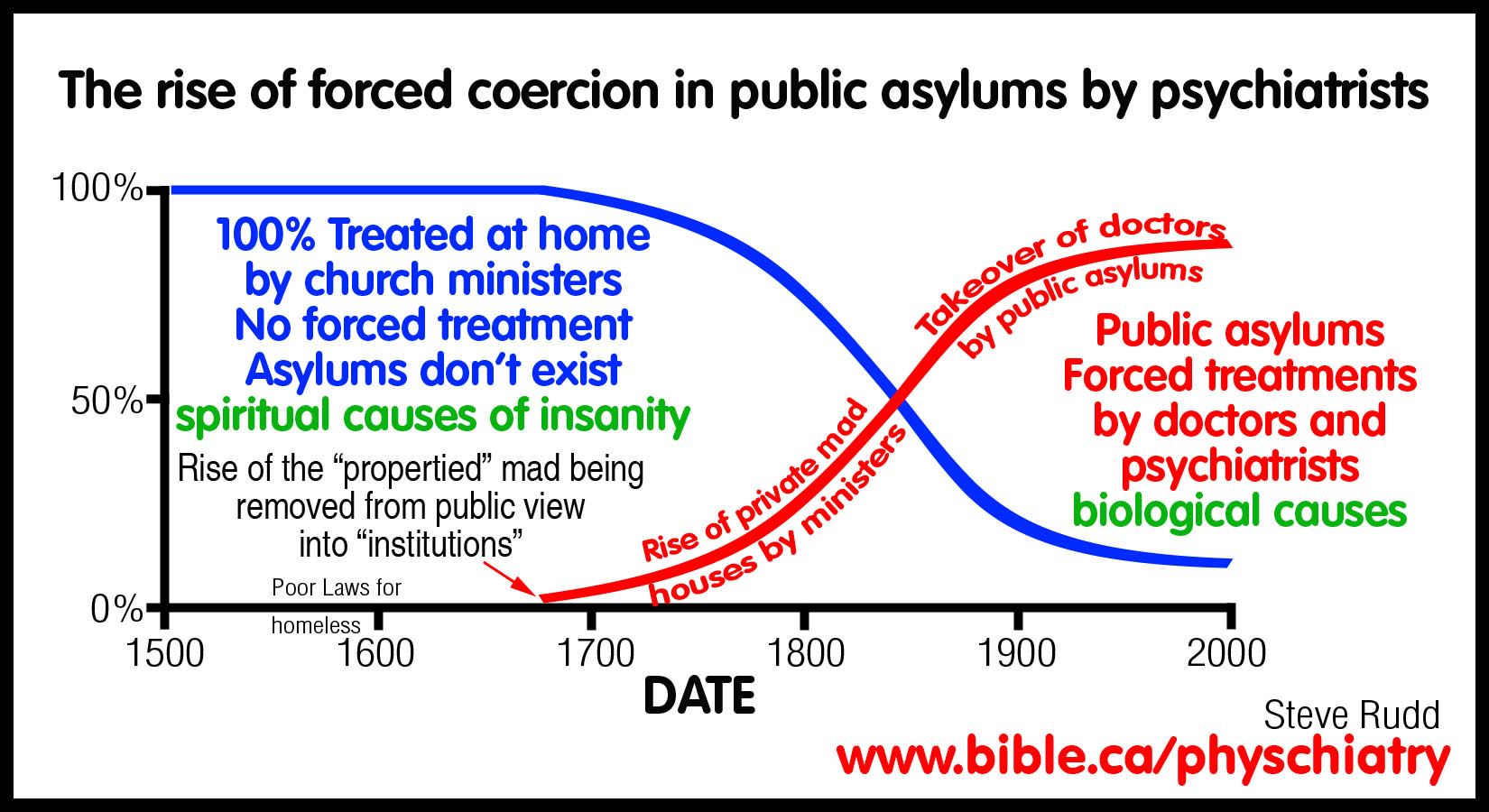

- The word psychiatrist literally means, "a doctor of the soul" and church ministers were the first psychiatrists who specialized in working with the insane. This makes sense since today's chemical psychiatrists don't even believe in God and reject the very existence of the human soul or spirit. This would make today's psychiatrists doctor's of something they do not believe exists!

- Church ministers were the first experts in helping to change the behaviours of the insane. They correctly understood insanity as a behaviour that needed correcting like any other sins like habitual stealing, adultery or selfishness.

- Institutional psychiatry had its origins as a parallel prison system as a form of behaviour and social control.

- "The fatal weakness of most psychiatric historiographies lies in the historians' failure to give sufficient weight to the role of coercion in psychiatry and to acknowledge that mad-doctoring had nothing to do with healing." (The Medicalization Of Everyday Life, Thomas Szasz, 2007 AD, p 55)

- Most of the "cure" or treatments were a form of torture with the purpose of making the insane person's life so miserable that they chose to change their behavior in conformity the social norms of the day.

- Hippocratic "humoral medicine" theory wrongly believed that insanity was caused by an imbalance in the four humors like melancholy blood. Bloodletting was commonly practiced to correct the imbalance. However church ministers believed that sinful living caused "melancholy blood" which in turn caused insanity. With the discovery of the cell in 1858 AD, humoralism went extinct and doctors suddenly realized that insanity was not caused by "bad blood".

- Today psychiatrists have replaced "humoral imbalances in the blood" with "chemical imbalances in the brain." However, there is no scientific proof that chemical imbalances of Serotonin exist in the brain of the insane, much less that they cause insanity. Humoral doctors "cured" by bloodletting. Chemical psychiatrists "cure" with drugs and shocks to the brain. In fact the only time a chemical imbalance can be documented is when they are induced by neuroleptic drugs prescribed by a psychiatrist.

- In the near future, the entire practice of chemical psychiatry will be extinct and share a place beside humoral medicine in the museum of junk science.

A. Court appointed guardians for the rich: 1300 - 1500 AD

- Insanity and mental illness were not differentiated from either the begging poor or the rich "propertied class" who became dependant on others for their day to day care.

- In medieval England between 1300 - 1500 AD, they convened were courts that appointed a kind of "power of estate" over anyone from among the "propertied class" who was either born incapable of caring for themselves or suffered and injury or disease or old age that incapacitated them.

- These court appointed "guardians" were for the rich only. The poor looked to their relatives, their feudal lord or their local church for benevolence.

- "Medieval English society was based on the preservation and stable transmission of landed wealth. Consequently, as early as the thirteenth century, the king was entitled to take possession of the person and estate of mentally ill subjects who were incapable of managing their own affairs." (Diagnosis, Guardianship, and Residential Care of the Mentally Ill in Medieval and Early Modern England, Richard Neugebauer, American Journal of Psychiatry Dec 1989 AD)

- A close look at the original historical data shows us that 1300 to 1700 AD, there were only two classes of those "incapable of managing their own affairs": 1. the "idiot" who was (a) born that way (i.e. Downs) or (b) suffered a permanent injury to the head and 2. the "Lunatic" who had been fully self sufficient most of their life, but through (a) disease or (b) injury causing or (c) emotional choice based upon life events or circumstances, had become dependant. "The jurisdiction employed two major medicolegal categories: "idiot" and "lunatic." "Idiot" denoted persons who were mentally subnormal from birth, without hope of improvement. "Lunatics" exhibited psychotic behavior but were judged capable of recovery ... mental status tests and etiologic concepts changed little over these centuries" (Diagnosis, Guardianship, and Residential Care of the Mentally Ill in Medieval and Early Modern England, Richard Neugebauer, American Journal of Psychiatry Dec 1989 AD)

- It is important to note that the "lunatics" were viewed as being able to recover, but the "idiots" were seen as incurable. It is more important to note, that a person who suffered from a brain injury was considered a "lunatic" and needed a "lunatic keeper" to care for him, but was certainly not "insane" or "mentally ill".

- Unlike "idiots", "lunatics" were considered curable since their was hope they might recover from an injury or disease or poisoning.

- Of course those who had nothing physically wrong with them were always considered curable since it was usually clear their "dependency" was a choice they had made in response to: psychological factors like emotional trauma, social stress, lovesickness, financial loss, psychological abuse etc.

- From the original documents the only determining factor that the courts looked for when they appointed "guardians" over an individual, was function: Could the person take care of themselves? They tested by seeking answers to simple mathematical questions, ability to use money to buy and sell, read, personal identify, awareness of current events, respectful moral conduct and how they maintained their personal appearance. These competency hearings are virtually identical to the process of modern psychiatric committal today. In both 1300 AD and 2011 AD a person is asked questions and observed in order to make a determination if the person able to care for themselves. Today, as in medieval times, no blood is tested, no fMRI's are done, it is all a matter of subjective opinion based upon how the person has chosen to both present themselves and how they chose to answer. There was no way of determining if a person was deliberately lying or getting questions wrong.

- The historic role that church ministers played in dealing with those who were physically healthy, but behaved in annoying and bothersome ways to others, is seen in this fact: "Boarding out the lunatic or idiot at a private dwelling, in the company of a servant, was also commonplace; this practice in some respects anticipated the development of private madhouses in the eighteenth [and 17th] century ... Role Of The Medical Profession: Apart from an incidental appearance as a guardian, what role did physicians play in this jurisdiction? ... physicians played essentially no role in the certification process itself." (Diagnosis, Guardianship, and Residential Care of the Mentally Ill in Medieval and Early Modern England, Richard Neugebauer, American Journal of Psychiatry Dec 1989 AD)

- Not only did doctors have no role in confining the insane, they did not treat them. Doctors generally viewed the "insane" as being untreatable by them using "physic". Exactly what could a doctor do to treat these people? Nothing! However, if they had received a blow to the head or suffered from some disease or poising that induced dementia, they were the first to be called in, being an obvious medical matter. There were also cons who claimed, like modern psychiatrists, to be able to cure a person of annoying and antisocial behaviours that others disliked.

- While there are a few isolated cases of doctors taking "lunatics" into their homes for private treatment, it is clear that these were disabled people who had hope of recovering from an injury or disease apparent to all. There is no evidence that doctors every took anyone into their homes who were fit and healthy, but behaved in annoying, offensive. The people who are labeled "mentally ill" today would never be taken into a doctor's home because there was nothing medically wrong with them. Changes in behaviours were the sole domain of church ministers until about 1675 AD.

- It is clear that in 1300 AD as in today, that there were people who had nothing wrong with their bodies who became dependant and the courts appointed a close relative as a kind of power of attorney in order to protect themselves and their families from financial ruin. These were cared for by a close relative, but never strangers or medical doctors.

- There are always reasons for human behaviour only God reads the hearts and only Christ can provide peace, hope, forgiveness, purpose and joy!

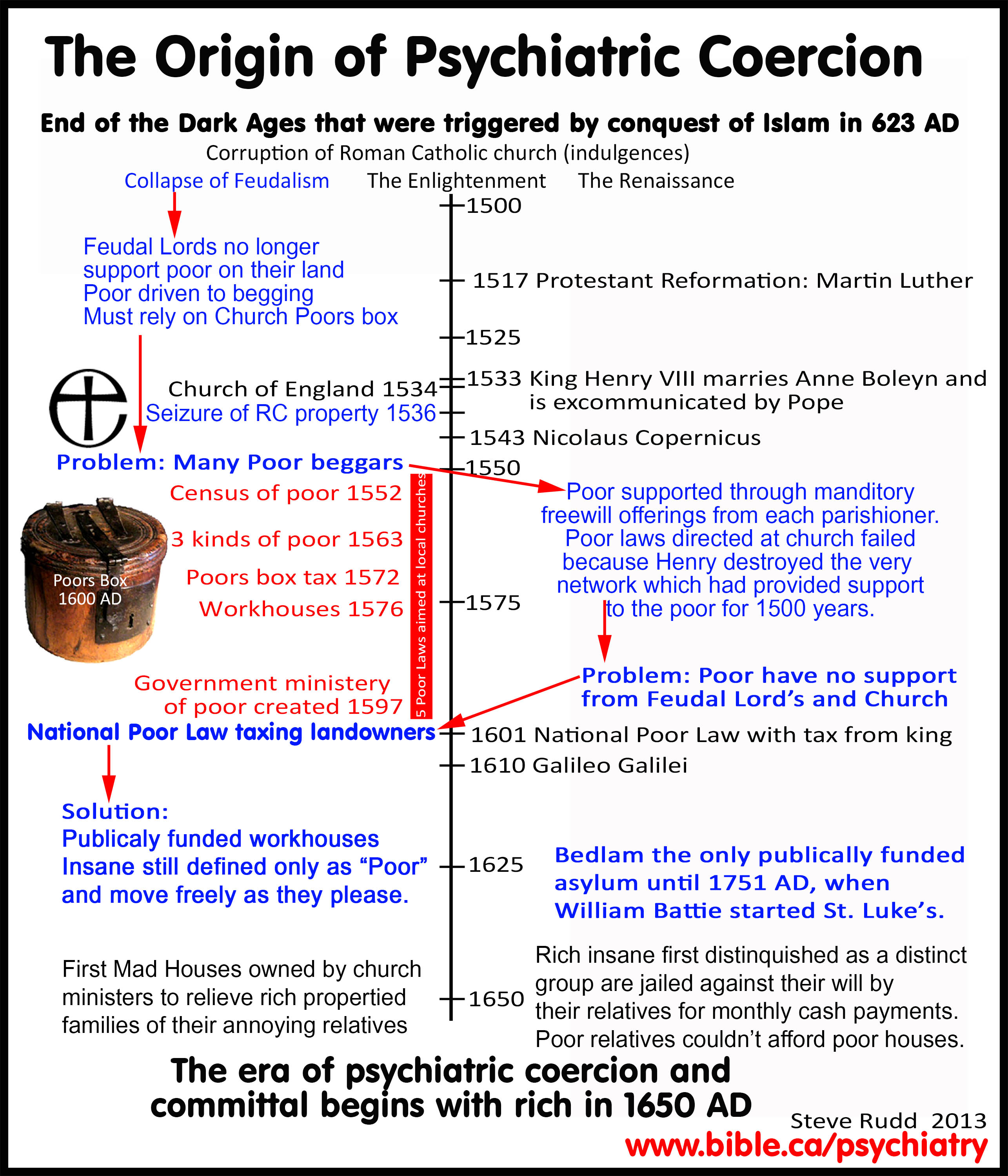

B. Summary of earliest changes that led to psychiatric committal: 1500 - 1600 AD

- The first time in history the insane were jailed in a privately owned mad house was about 1650 AD. Apart from Bedlam, there were almost no public asylums in the world until about 1800 AD.

- The world turned upside down in the 16th century. By 1600 AD, a perfect storm of change was sweeping through England.

- "The genesis of psychiatry as a modern science must be seen against the background of a movement that radically changed the social landscape of seventeenth-century Europe. The Age of Reason, mercantilism, and enlightened absolutism coincided with a new and rigorous spatial orientation. It put all forms of unreason, which in the Middle Ages had been part of a divine world and in the Renaissance a secularizing world, the civil world of commerce, morality, and work, in short — beyond the pale of the rational world — under lock and key. Beggars and vagabonds, those without property, jobs or trades, criminals, political gadflies and heretics, prostitutes, libertines, syphilitics, alcoholics, lunatics, idiots, and eccentrics, but also rejected wives, deflowered daughters, and spendthrift sons were thus rendered harmless and virtually invisible." (Madmen and the Bourgeoisie, Klaus Doerner, 1969 AD, p 14)

- For almost 1000 years, the "dark ages" were dominated by the Roman Catholic church controlling the world and every aspect of society.

- In 1543 AD, Nicolaus Copernicus proclaims the sun is the centre of the universe and Galileo Galilei born in Italy in 1564 AD. The age of scientific discovery, free thinking and the protestant reformation were at hand.

- The collapse of the feudal system, where landowners were mini-kingdoms unto themselves charged with the care and control of all who lived within their land, created a population of unemployed vagrants. The collapse of the feudal system drove the poor from under the care of feudal lords and off the land to become beggars in the city.

- Marxist-Leninist, Michel Foucault's view that as leper houses emptied out because of cures, the empty buildings began to house the insane, is simply untrue. Foucault lets his desire to paint the rise of asylums as a class war where the rich oppressing the poor is also pure fiction. What do you expect from a French, communist university professor? Michel Foucault says: "England and Scotland alone had opened 220 lazar [leper] houses for a million and a half inhabitants in the twelfth century. But as early as the fourteenth century they began to empty out; by the time Edward III ordered 'an inquiry into the hospital of Ripon—in 1342—there were no more lepers; he assigned the institution's effects to the poor. At the end of the twelfth century, Archbishop Puisel had founded a hospital in which by 1434 only two beds were reserved for lepers, should any be found. In 1348, the great leprosarium of Saint Albans contained only three patients; the hospital of Romenal in Kent was abandoned twenty-four years later, for lack of lepers. At Chatham, the lazar house of Saint Bartholomew, established in 1078, had been one of the most important in England; under Elizabeth, it cared for only two patients; it was finally closed in 1627. The same regression of leprosy occurred in Germany, perhaps a little more slowly; and the same conversion of the lazar houses, hastened by the Reformation, which left municipal administrations in charge of welfare and hospital establishments; this was the case in Leipzig, in Munich, in Hamburg. In 1542, the effects of the lazar houses of Schles-wig-Holstein were transferred to the hospitals. In Stuttgart a magistrate's report of 1589 indicates that for fifty years already there had been no lepers in the house provided for them. At Lipplingen, the lazar house was soon peopled with incurables and madmen. ... Leprosy disappeared, the leper vanished, or almost, from memory; these structures remained. Often, in these same places, the formulas of exclusion would be repeated, strangely similar two or three centuries later. Poor vaga-bonds, criminals, and "deranged minds" would take the part played by the leper, and we shall see what salvation was expected from this exclusion, for them and for those who excluded them as well." (Madness and Civilization, Michel Foucault, 1965 AD, p5,7)

- "Although the historical record is clear, Michel Foucault constructed a history of psychiatry that has confused the matter. Influenced by his Marxist bias, he traced the origin of the practice of incarcerating madmen to the segregation of lepers and, more specifically, to the large-scale confinement of urban indigents in France in the seventeenth century.' Although some of what Foucault described did happen, it was not the way the systematic confinement of persons diagnosed as mad came into being. Individual rights were virtually nonexistent in seventeenth-century France. They were assuredly nonexistent for the propertyless French masses. Hence, imprisoning the rabble in "general hospitals" did not require the pretext of insanity as an illness. It is simply not true that institutional psychiatry represented the beginning of a new mode of warfare between the haves and have-nots, the former resorting to the tactic of labeling the latter as insane in order to remove them to the madhouse. The incarceration of rich persons in private madhouses came first and was followed, considerably later, by the incarceration of poor persons in public insane asylums. Roy Porter emphasizes that psychiatry was not "a discipline for controlling the rabble. . . . Provision of public asylums did not become mandatory until 1845. . . . Even at the close of the eighteenth century, the tally of the confined mad poor in Bristol, a town of some 30,000, was only twenty. . . . [Whereas] about 400 people a year were being admitted to private asylums."Roy Porter, Mind-Forg'd Manacles: A History of Madness from the Restoration to the Regency (London: Athlone Press, 1987), 8-9.) " (The Medicalization Of Everyday Life, Thomas Szasz, 2007 AD, p 62)

- The divorce of King Henry the 8th got himself labeled a heretic for divorcing and remarrying contrary to the Bible. He started the church of England and seized most of the assets of the Roman catholic church in England. This led to the collapse of the moral and social welfare system run by priests.

- The poor, once supported by feudal lords and by the church, found themselves "wards of the state", having no other place to turn. This was the consequence of the separation of church and state.

- Laws were passed outlawing begging and a new poor tax was extracted from the general public to support the poor from public coffers much like today.

- The state created work houses for the poor, unemployed and homeless that were once under the guardianship of feudal lords and the benevolence of their local church.

- Harsh punishments for crimes, including begging and vagrancy were decreed including: Boiling in oil, water or molten lead, Branding, Branding Irons, Burning, compressing, Cutting , Cutting off of hands, ears, feet, Ducking stools, Starvation in the public square, The Collar , The Drunkards Cloak, The Gossip's Bridle (or Brank), The Iron Maiden, The Pillory and Stocks, The Rack, The Scavenger's Daughter , The Wheel, Thumbscrews, Whipping.

- At this time, the insane were not distinguished from others who were dependant beggars.

- Insanity was correctly viewed as a sinful choice of behaviour where church ministers were the experts in dealing with them.

C. The corruption of the Roman Catholic church: 1500 AD

- This monopolistic power led to theological, moral and civil corruption in the way the church governed.

- The sale of indulgences to built St. Peter's basilica in Rome, for the Pope's personal pleasure, became the ultimate symbol of this corruption. Construction started in 1507 AD and ended in 1626 AD.

D. The protestant reformation: 1517 AD

- In 1517 AD, Martin Luther publishes the Ninety-Five Theses against indulgences and triggers the protestant revolt against the Roman Catholic church beginning in Germany. Sadly today, the country that triggered the greatest campaign to get "back to the Bible" is now populated by one of the highest number of atheists per capita in the world!

- Perhaps because Luther challenged the church, King Henry was emboldened to start the church of England.

- The beginning of the renaissance and free thought had begun. The world was about to be transformed religiously where Christians cared less about what religious leaders taught and more what the Bible commanded.

E. The divorce that triggered social revolution: 1534 AD

- In 1533 AD, King Henry VIII is refused a divorce from Catherine of Aragon by the Pope, but marries the pregnant Anne Boleyn anyway. excommunicated

- After the Pope excommunicates Henry in 1534 AD.

- Just as the lax morals of the pot smoking hippies of the 1960's triggered the collapse of Christianity, church attendance and morality, so too the divorce of King Henry VIII triggered a chain of events that forever changed the world!

F. Destruction of Roman Catholic church in England: 1534 AD

- In 1536 AD, King Henry VIII banishes the Roman Catholic church in England and replaces it with the Church of England and makes himself the "pope". This unbelievably evil action by a monarch to rationalize his adultery had far reaching social consequences. The Church was the historic foundation of the support of the poor. Henry destroyed this welfare network of 15,000 local churches [parishes] that were already caring for their poor out of Christian obligation and suddenly the poor had no support at all. Queen Elizabeth was forced to make the state care for the poor through general mandatory taxation. He killed a working system of voluntary altruistic Christian almsgiving. Volunteerism always works better than any government program that tries to replace it.

- "Thus, after a brief flurry of activity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the poor, including the insane poor, continued to be dealt with on a local, parish level— though under the Poor Law Act of 1601 (43 Elizabeth c. 20) they were now acknowledged to be a secular rather than a religious responsibility. In consequence, as many as 15,000 separate administrative units were involved in the management of the poor; and the pervasive emphasis on localism was further reinforced by the custom of restricting aid to those belonging to one's own parish, a custom which received statutory recognition in the 1662 Act of Settlement (14 Charles II c. 12)." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 15)

- In 1536 AD, the king confiscates the Catholic monasteries which were the centres of social welfare, control and morality. Church ministers, once at the centre of everyday living, were themselves forced into unemployed poverty and stripped of their influence and power. This is the beginning of the separation of church and state, and such a change had huge unexpected consequences for the king. Before his action, members of each local church were commanded by the ministers to support the poor with gifts of alms based upon the Gospel of Jesus. Before Roman Catholic priests and monasteries were abolished in England, the church was the central authority in teaching on the basis of the Gospel, that the poor needed to be supported.

- "The first (largely abortive) efforts to break with medieval precedent in dealing with the poor came in the sixteenth century. Throughout Western Europe in this period, the efforts of centralizing monarchs to augment state power produced a series of clashes between Church and state. In England, this conflict led to a decisive subordination of the former to secular political authority, and greatly accelerated the diminution of the Church's role in civil society. The dissolution of the monasteries and the redistribution of monastic lands were both symptoms and causes of this decline, a decline which rendered a Church-based response to the indigent increasingly anachronistic and unworkable." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 11)

- Three Bible passages

commonly used by the church to support the poor were: "The man who

has two tunics is to share with him who has none; and he who has food is

to do likewise." " (Luke 3:11)

"Then the King will say to those on His right, 'Come, you who are blessed of My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. 'For I was hungry, and you gave Me something to eat; I was thirsty, and you gave Me something to drink; I was a stranger, and you invited Me in; naked, and you clothed Me; I was sick, and you visited Me; I was in prison, and you came to Me.' "Then the righteous will answer Him, 'Lord, when did we see You hungry? ... "The King will answer 'Truly I say to you, to the extent that you did it to one of these brothers of Mine, even the least of them, you did it to Me.' " (Matthew 25:34-40)

"If a brother or sister is without clothing and in need of daily food, and one of you says to them, "Go in peace, be warmed and be filled," and yet you do not give them what is necessary for their body, what use is that? Even so faith, if it has no works, is dead, being by itself. " (James 2:15-17) - After England displaced a well established Roman catholic system of moral guidance and welfare towards the poor, there was a general moral decay and neglect for the poor altogether.

- This collapse was caused by four factors, two of which were the result of King Henry VIII himself. The Renaissance and the reformation were two factors that predated Henry, where as rebellion against the Bible in a wicked divorce and destroying the church out of spite were two factors created by Henry. "If the king can get a divorce... so can I" was a powerful attitude that permeates English thinking even to the present time. The lawlessness and immorality came from the top down and rested on the general public.

G. The English Poor laws: 1552 - 1601 AD

- The Elizabethan dynasty is faced with a collapse of morality, religion, civil and social structure. There was a mass migration away from the feudal lands to the cities causing a dramatic increase in the unemployed poor.

- A series of "poor laws" were passed where the state stepped in to take over from the work of the church it destroyed.

- English Royal decrees and "Acts" were passed in 1552, 1563, 1572, 1576 and 1597 which obligated each local church to provide for the poor. However, having just destroyed the very church network (Roman Catholic church) and confiscated their land and buildings, these laws were essentially ignored by the church that remained. The decrees that tried to continue the ancient tradition of churches helping the poor were a failure so the king turned to the general public for taxation.

- The Poor Law of 1552 AD, order a census to count the poor within each of the 15,000 parishes (local churches with a single minister).

- In 1553 AD, King Henry 8th gave his "Bridwell palace" to the city of London and it became a jail for the poor. "From the end of the sixteenth century and throughout the seventeenth ... punitive functions were assumed by the houses of correction or 'Bridewells', modeled on the original London foundation. As well as being for 'vagrants and beggars who could not be convicted of any crime save that of wandering abroad or refusing to work',' such places served as houses of confinement for the more dangerous or troublesome lunatics." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 16)

- The Poor Law of 1563 AD created three categories of poor: The 'Deserving Poor': unemployable widows, orphans and the sick. The 'Deserving Unemployed': the unemployed. The 'Undeserving Poor': those who refused to work, criminals, vagrants. The insane were not differentiated from the 'Undeserving Poor'. Aid was distributed to the two categories of the deserving poor. The undeserving were ordered to be punished, whipped, beaten and tortured.

- The English Poor Law of 1572 AD ordered each local church to support and care for the poor that were inside their domain (parish). This failed.

- The English Poor Law of 1576 AD created "Workhouses" (work, food and shelter), "Poorhouses" (work, food but no shelter) and "Houses of Correction" to discipline and torture the "unworthy poor" into being self sufficient. Unwed mothers were a special category who were singled out for punishment, along with the father.

- "By modern standards, most of these eighteenth-century institutions possessed a peculiarly mixed character. Workhouses, for example, despite their name and the intentions of their founders, became dumping grounds for the decrepit and dependent of all descriptions. Prisons mixed young and old, men and women, debtors and felons, in a single heterogeneous mass." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 18)

- "In England, the same development had begun earlier, with certain differences. Laws ordering the building of houses of correction had already been passed by 1575. But the idea did not take hold, despite threats of fines and inducements to private entrepreneurs, and despite the existing policy of enclosures (which allowed large landowners to streamline farming and send a flood of "freed" and landless peasants into the towns)." Scotland resisted almost completely. Generally what happened was an expansion of existing prisons. The establishment of workhouses was more successful; some 126 went up between 1697 (Bristol) and the end of the eighteenth century, mainly in newly industrialized regions." (Madmen and the Bourgeoisie, Klaus Doerner, 1969 AD, p 15)

- The English Poor Law of 1597 AD created a special new authority called the 'Overseer of the Poor' who set poor tax rates for each local church, tax collection from landowners, oversight of distribution to poor and supervision of the poor houses and work houses.

- Queen Elizabeth had no choice but to support the poor from general taxation of the working public and the rich. She passed the formal Poor Law in 1601 AD.

- The English Poor Law of 1601 AD transformed the entire system from a local church "grassroots" organization that appealed up to landowners, to a nation wide organization from the King down to the landowners.

- "The Poor Law Act of 1601, 43 Eliz., c. 2, served to focus attention on the poor and unemployed, but no separate provisions for the insane were made and harmless lunatics and idiots continued to be left at liberty as long as they were not considered to be dangerous and caused no social disturbance. However, a change in social attitudes towards lunatics in the community was to take place in the seventeenth century. This marked the beginning throughout Europe of the period of 'The Great Confinement ' of the insane in company with criminals, vagrants and the unemployed, a process that was reflected in England in the increasing use for this purpose of houses of correction and, later, the workhouses. " (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p 6-8)

- "In 1630, the [British] King established a commission to assure the rigorous observance of the Poor Laws. That same year, it published a series of "orders and directions"; it recommended prosecuting beggars and vagabonds, as well as "all those who live in idleness and will not work for reasonable wages or who spend what they have in taverns." They must be punished according to law and placed in houses of correction; as for those with wives and children, investigation must be made as to whether they were married and their children baptized, "for these people live like savages without being married, nor buried, nor baptized; and it is this licentious liberty which causes so many to rejoice in vagabondage." Despite the recovery that began in England in the middle of the century, the problem was still unsolved in Cromwell's time, for the Lord Mayor complains of "this vermin that troops about the city, disturbing public order, assaulting carriages, demanding alms with loud cries at the doors of churches and private houses." (Madness and Civilization, Michel Foucault, 1965 AD, p 50)

- At this point, the insane were not differentiated from within the poor, but the seed of institutionalization from the state was firmly planted. The way was paved for the rise of private mad houses run by church ministers in 1650 AD.

- In France, the General Hospital was established in 1653 AD and a "poor law" passed in 1657 AD that outlawed begging: "We expressly prohibit and forbid all persons of either sex, of any locality and of any age, of whatever breeding and birth, and in whatever condition they may be, able-bodied or invalid, sick or convalescent, curable or incurable, to beg in the city and suburbs of Paris, neither in the churches, nor at the doors of such, nor at the doors of houses nor in the streets, nor anywhere else in public, nor in secret, by day or night ... under pain of being whipped for the first offense, and for the second condemned to the galleys if men and boys, banished if women and girls." (French edict of 1659, paragraph 9)

- England passed a law in 1714 AD, which defined all homeless beggars as being insane. This further illustrates that the insane were not differentiated from other dependant beggars and vagrants. But this strange law was a method of legally jailing street people who had committed no crime (except vagrancy and begging itself which were illegal). By defining all beggars as "insane", it provided a new legal method of restricting a person's freedom from being thrown in jail without committing a crime. It is one of the earliest versions of the "not responsible for reasons of insanity" idea which deemed the insane needed other's to take control of them in order to "clean up the streets of street beggars". "In 1714, an Act of Parliament for the first time took up the subject of "the more effectual punishing [of] such rogues, vagabonds, sturdy beggars, and vagrants," calling for their confinement insofar as they were "furiously mad,"" (Madmen and the Bourgeoisie, Klaus Doerner, 1969 AD, p 20)

- "The Act of 1714, 12 Anne, c. 23, distinguished, for the first time, between impoverished lunatics and ' Rogues, Vagabonds, Sturdy Beggars and Vagrants'. It was enacted that two or more justices of the peace could authorize the apprehension of lunatics who were `furiously mad, and dangerous', by the town or parish officials, and order their confinement, `safely locked up, in such secure place . . . as such justices shall . . . direct and appoint', where, if necessary, the lunatic could be chained. Apart from such restraint, which was to be applied only during the period of madness, no treatment was provided for, although the lunatic was exempted from whipping. The cost of detention, in the case of pauper lunatics, had to be paid out of the funds of the lunatic's parish [his home church] of legal settlement. The charge for `curing' such persons was added to these expenses by the Vagrant Act of 1744, 17 Geo. II, c. 5, which was essentially a re-statement of the Act of 1714. It is likely that the provisions of the latter reflected the prevailing practice during the late seventeenth century." (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p 6-8)

H. The era of no committal: before 1650 AD:

- The earliest form of jailing the mentally ill, as a separate and distinct group, did not exist before about 1650 AD. Before 1650 AD, the insane were viewed as lazy, dependant, freeloading, poor vagrants who lived immoral lives and conducted themselves in ways that annoyed and bothered others with their lifestyle choices.

- "The Social Control of the Mad: The typical response to the deranged underwent dramatic changes between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. At the outset of this period, mad people for the most part were not treated even as a separate category or type of deviants. Rather, impoverished madmen were assimilated into the much larger, more amorphous class of the morally disreputable, the poor, and the impotent, a group which also included vagrants, minor criminals, and the physically handicapped; and their richer (though not necessarily more fortunate) counterparts were for the most part coped with by their families. Furthermore, just as in the case of the indigent generally, the societal response to the problems posed by the presence of mentally disturbed individuals did not involve segregating them into separate receptacles designed to keep them apart from the rest of society. The overwhelming majority of the insane were still to be found at large in the community. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, virtually no aspect of this traditional response remained intact. The insane were clearly and sharply distinguished from other 'problem populations'. They found themselves incarcerated in a specialized, bureaucratically organized, state-supported asylum system which isolated them both physically and symbolically from the larger society." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 1)

- "AT THE BEGINNING of the seventeenth century (1600 AD), there were no mental hospitals, as we now know them. To be sure, there were a few facilities— such as Bethlehem Hospital, better known as Bedlam—in which a small number, usually less than a dozen, of pauper insane were confined. By the end of the century, however, there was a flourishing new industry, called the "trade in lunacy."' To understand the modern concept of mental illness, one must focus on the radically different origins of the medical and psychiatric professions. Medicine began with sick persons seeking relief from their suffering. Psychiatry began with the relatives of unwanted, troublesome persons seeking relief from the embarrassment and suffering their kin caused them. Unlike the regular doctor, the early psychiatrist, called mad-doctor, treated persons who did not want to be his patients, and whose ailments manifested themselves by exciting the resentment of their relatives. These are critical issues never to be lost sight of Annoying, unconventional behavior must have existed for as long as human beings have lived together in society." (The Medicalization Of Everyday Life, Thomas Szasz, 2007 AD, p 55)

- The insane were under the jurisdiction of church ministers and churches, just like any other willful sin: "For at least two centuries (the thirteenth and fourteenth) the plight of the mentally ill was entirely the domain of the theologians, whilst lay physicians dealt as best they could with the organic problems of the body." (Bedlam, Anthony Masters, 1977 AD, p26)

- "Those who remained permanently insane (unless they happened to come from the propertied classes) did not pose a unique problem, but formed part of the larger class of the really poor and impotent: the senile, the incurably ill, the blind, the crippled, and the maimed. Efforts were made to keep these people in the community, if necessary by providing their relatives or others who were prepared to care for them with permanent pensions for their support." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 15)

- "WHILST there is little information regarding the precise treatment of the insane in medieval times, there is evidence that the mentally afflicted were accommodated at times alongside the physically diseased in the infirmaries of the period. In addition, monastic houses [church run shelters under the control of church ministers] often gave shelter to lunatics in company with vagabonds and vagrants." (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p 6)

- See our outline: Church ministers were the first psychiatrists.

- Before the series of English "Poor Laws" of 1552 - 1601 AD, they roamed freely throughout the community like any other peasant beggar. As these poor laws were passed and begging was outlawed, the insane were swept up with all the other beggars and put in workhouses or sent to jail to be tortured to become self sufficient. The insane who owned property or were not "homeless" continued to live in their homes usually under the supervision, advice and council of church ministers. It was not until about 1650 AD, that these same church ministers who would make house calls to the homes of the insane, were offered money by their relatives to remove the insane family member from the home into a "boarding home" under the control of the preacher.

- Commenting on the situation of insanity on American soil: "In seventeenth-century (1600 - 1699 AD) America the mentally ill received scant attention. The raw frontier life in the thin line of settlements stretching along the Atlantic coast gave colonists little time or opportunity to cope with the problems of society's unfortunates. Preoccupied with the basic issues of subsistence, people remained indifferent to irregular behavior unless it posed a threat to public order. Indeed, colonists equated insanity with disruptive, violent, and deviant conduct, and assumed that it was caused by either demonological possession or moral turpitude. Religious authorities prompted the view that erratic behavior signified a person's compact with diabolical, supernatural forces by arguing that a possessed individual acted wildly, had unusual strength, made animal noises, and often spoke a language that had not been learned. Cotton Mather, the controversial Puritan clergyman and author who saw the mentally ill as agents of Satan, commented that the possessed had "melancholy and spiritual delusions" and were "taken with very strange fits." His publications, Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions and Wonders of the Invisible World, elaborated on satanic possession. He and others deemed madness God's punishment for moral corruption. In his unpublished medicoreligious study, The Angel of Bethesda, Mather combined religious concepts with medicine and identified sin with "a sickness of the mind." The connection between sin and insanity became a potent belief in colonial America, much stronger and more widespread than the assumption of the devil's power to influence human behavior. Colonists took religion seriously and adhered to a strict moral code. Ministers extolled their congregations to pursue virtuous lives; they warned that God avenged the practice of immorality; He brought "frightful diseases" and an early death. Although presumably "distempered in the head," the deviant—a damnable sinner—was a wicked, inferior subhuman who had lost all rights and privileges. Sinful behavior naturally demanded retribution, and colonists meted out harsh punishments to the transgressor. Cruel treatment, including whippings and beatings, was believed necessary to purge the afflicted of sin and terrorize him or her back to sanity. The link that colonists made between insanity and immorality set a pattern for identifying the mentally ill in America. Members of any society have always found it easy to mark its outcasts as mentally deranged. Seventeenth-century Americans placed the morally deviant in this category. Social and intellectual nonconformists, the aged, the poor, and minorities have, in like manner, felt not only the pain of ostracism but also the brunt of false charges regarding their sanity. Equally fundamental to the American efforts to look after the insane has been the differing qualities of care given to the mentally ill of different socio-economic classes. The affluent patient received the best treatment, often on an individualized basis and with refined techniques; the poorer patient received custodial care combined with frequently violent treatment. The relationship between therapy and a person's position in society developed most sharply in the early nineteenth century, when a system known as moral treatment was introduced in American mental institutions. But in the seventeenth century the distinction was blurred by the prevailing negative attitudes toward insanity and the crude, exotic remedies applied to cure it. The upper- and middle-class sick found relief within the family. Here the afflicted individual may have received solace from relatives and a family physician. The existing moral condemnation of the mentally ill may have encouraged some affluent households, sensitive to community ridicule, to hide the disturbed family member in the cellar or in the attic, chained to a bed or a post. If the family milieu itself contributed to a person's disorder, home care became a private hell. A typical physician attending the insane in seventeenth-century America administered an assortment of concoctions made from such ingredients as human saliva and perspiration, earthworms, powdered dog lice, or crab eyes. Special importance was attributed to an herb called Saint-John's-wort, which was blessed, wrapped in paper, and inhaled to ward off attacks from the devil. Astrological lore found expression in prescriptions: one physician instructed that bloodletting and blistering be timed with phases of the moon; another called for boiling live toads in March and then pulverizing them into powder, a delicacy credited with preventing and curing all kinds of diseases. From his medical treatises a doctor might prescribe ancient and medieval remedies. Hellebore, an herb used by the ancient Greeks to cure mental disorders, was specified as being "good for mad and furious men." A preparation known as "spirit of skull" involved mixing wine with moss taken from the skull of an unburied man who had met a violent death. Hot human blood, as well as pulverized human hearts or brains, presumably helped to control "fits." While these prescriptions represented the best known "cures," the nauseating quality of the mixtures suggests that the remedy rather than the illness was the more formidable obstacle to recovery. Vomiting may actually have been helpful, and certainly had powerful psychological effects. In any event, the "cures" reflect the state of medical knowledge in colonial America, a time when physicians and laymen read and used the same medical recipe books. Most doctors remained preoccupied with common maladies and epidemics. The care of the indigent insane was covered by informal local arrangements, a custom derived from the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, which made each town responsible for its needy. A typical colonial New England statute might be entitled "An Act for the Relief of Idiots and Distracted Persons," and it would identify the community as the legal and responsible guardian of the mentally disturbed individual. The insane were accepted as community wards because of their inability to sustain themselves rather than because of their disordered mental state. Occasionally a village shirked this duty. Under the cover of night, officials eager to rid themselves of a community burden would kidnap and transport a homeless victim to another village. At other times these harmless individuals, half-naked and ill-fed, were permitted to drift from place to place, subject to the taunts and abuse of local thugs. Strangers suspected of becoming public charges were ostracized and "warned out" of town, a harsh practice mercilessly applied to pregnant women and the sick as well as to the mentally disturbed. The physically able insane were often auctioned, like slaves, to persons who would use their labor in return for caring for them. The object of this custom was to dispose of public wards at nominal cost to the community. Considered a danger or a nuisance to public order, violent cases were sometimes placed in cages, kennels, or blockhouses, where they were chained and whipped. In providing relief, colonial towns made no distinction among the mentally ill, criminals, orphans, the sick, the aged, the physically maimed, and the unemployed. These undifferentiated dependents were thrown together in jails and workhouses. Here they remained in dingy cells, attics, or cellars, treated with scorn and indifference, and allowed to vegetate and suffer alone. This condition persisted throughout the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth century. No medical treatment was involved or available; care was strictly custodial. The pauper insane were particularly unfortunate, lacking both family and friends. While this general condition of indigent groups demonstrated the inhumanity and the insensitivity of the wider society toward the poor, the situation was not unique to colonial America. The practice today of discharging mental patients, who have no social nor financial means, into the community, where they must reside in dismal slum hotels, can hardly be viewed as an enlightened policy. The history of mental health care is not a success story or a story of progress; it does not follow a straight-line development from grim, torture-like activities of early times to benign, enlightened practices of the present. Indeed, the harsh realities of colonial life dictated a harsh policy toward indigent groups. Colonists were subject to Indian attacks, and they faced such natural calamities as famine and epidemics. Idleness and vagrancy were viewed with disdain. Cooperative group effort sustained a community, and any form of dependency became a burden, an obstacle that threatened community survival. Social dependents thus were not only morally reprehensible, but also required controls and restrictions so that they could not undermine the cohesive fabric of society." (Treating the mentally ill, Leland V Bell, 1980 AD, p 1-4)

I. The era of the private madhouse: 1650-1800 AD

- "From a historical viewpoint, the madhouse system may be seen to comprise three relatively distinct phases. Firstly, a period extending from the first emergence of private madhouses, as named places of confinement, in the mid-seventeenth century, up to the latter end of the eighteenth century, a phase which represents the rise of the private-madhouse system but which is the least well documented. Secondly, a period which covers the last quarter of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century and which can be called the heyday of the system. Thirdly, a period of decline, covering the remainder of the lifespan of the private-madhouse system. It was during the second period that private licensed houses attained their greatest prominence and fulfilled their most important role. " (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p 282)

- Rich (who either owned land or lived in family owned houses) and poor (propertyless) alike were not coerced or placed into mad houses or asylums. Instead they lived and moved among the community like everyone else. If they broke laws, they would be tried, punished and jailed like any other persons. Since the insane are typically characterized by living a life of dependence, laziness and behaviour others fine annoying, they were not seen as sick, or needing a doctor. They were viewed as being part of the general begging class of vagrants if they were homeless.

- Those who owned property were cared for by their rich relatives in their own homes and also lived and moved freely throughout society like anybody else.

- "In England, as I shall show, there was no substantial state-led move to confine the mad (or the poor, come to that) during the seventeenth or the eighteenth century. Indeed, the management of the mad on this side of the Channel remained ad hoc and unsystematic, with most madmen kept at home or left to roam the countryside, while that small fraction who were confined could generally be found in the small madhouses which made up the newly emerging 'trade in lunacy'. There was, as we shall see, no English 'exorcism' of madness; no serious attempt to police pauper madmen (on the contrary, a sizeable fraction of the clientele of the new madhouses came from the affluent classes, necessarily so if the new entrepreneurial system was to flourish); and so far from attempting to inculcate bourgeois work habits, as Roy Porter has commented, 'what truly characterised [life in the handful of eighteenth-century asylums] was idleness." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 8)

- "Partly because of the lack of any legal requirement for licensing or registration, partly because of the ephemeral nature of many of these establishments, and most importantly because one of the major attractions of the madhouse for the well-to-do was the promise it would draw a discreet veil over the madman's very existence, we lack an accurate estimate of even as basic a matter as the number of private madhouses in operation during the eighteenth century." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 20)

- "One of the origins of the madhouse system, at least so far as pauper lunatics were concerned, was the practice which developed from the mid-seventeenth century onwards of boarding them out 'at the expense of the parish [church], in private dwelling houses, which gradually acquired the description of "mad" houses'. Among the more affluent classes, insane relatives were most often cared for on an individual basis, for which purpose they were frequently placed 'in the custody of medical men or clergymen'." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 21)

- However the desire to remove the annoying, trouble making, lazy and embarrassing "insane" relative from contact with his family members, drove them to pay church ministers to house them away from home. The offer of a monthly cash payment to a church minister to provide food, clothing and shelter to remove the insane was made by the family of the insane. This was the solution to allow the family of the insane to live in peace and not have to bother "dealing with" their misbehaving relative. Since church ministers were already the "experts" on human behaviour, and since insanity is nothing other than bad human behaviour, they were the first ones that people turned to in dealing with the insane.

- The first mad houses were to accommodate the rich, not the poor who were unable to afford such a luxury to hire out the room and board of an insane family member. Only the rich had the money. Today, the rich will put their aged parents into an old folks home that might cost $5-20,000 per month. Just as such a private option is out of reach of the average working person today, so too was a private mad house out of reach for the peasant, propertyless class. Imagine how impossible it would be financially for a poor working class family to pay for one of their children to live in a hotel room for a year and have a servant 24 hours a day to care and feed them.

- "William Battie, prime mover in the foundation of St. Luke's, owned his own madhouses on the side - in Islington and Clerkenwell - to which he transferred the more well-to-do private patients who came his way. A self-made man, at his death he left an estate valued at the astonishing figure of between one and two hundred thousand pounds." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 19)

- The first insane people on earth to be segregated from the rest of society in a mad house were the propertied class. "In the seventeenth century, it is known that lunatics from the more affluent classes were cared for individually, often in the custody of medical men or clergymen." (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p 6-8)

- "One of the methods which had become adopted by the parishes for the disposal of lunatics placed in their charge was to board them out, at the expense of the parish, in private dwelling houses, which gradually acquired the description of `mad' houses. For example, it is known that such an establishment existed in the parish of Horningsham, Wiltshire, in 1770, the lease of which was taken over by the parish officers in that year. Boarding-out remained an important mode of management of lunatics and idiots until the mid-nineteenth century and, as has been observed by Fessler (1956), it constituted one of the roots of origin of the private-madhouse system." (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p 6-8)

- Before the series of English "Poor Laws" of 1552 - 1601 AD, the insane roamed freely throughout the community like any other peasant beggar. As these poor laws were passed and begging was outlawed, the insane were swept up with all the other beggars and put in workhouses or sent to jail to be tortured to become self sufficient. The insane who owned property or were not "homeless" continued to live in their homes usually under the supervision, advice and council of church ministers. It was not until about 1650 AD, that these same church ministers who would make house calls to the homes of the insane, were offered money by their relatives to remove the insane family member from the home into a "boarding home" under the control of the preacher.

- "In what way did a property-owning madman in England in, say, 1650 endanger his relatives? He did so in one or all of the following ways: personally, by embarrassing them; economically, by dissipating his assets; and physically, by attacking his relatives. In this connection, it is necessary to acknowledge that a person who spurns our core values—that life, liberty, and property are goods worth preserving—endangers not only himself and his relatives but, symbolically, society and the social fabric itself. The madman's embarrassing behavior gave his family impetus for hiding him; his improvidence, which provided an important conceptual bridge between the old notion of incompetence and the new idea of insanity, gave them an impetus for dealing with him as if he were incompetent. The law had long recognized mental retardation as a justification for placing the mentally deficient person under guardianship." (The Medicalization Of Everyday Life, Thomas Szasz, 2007 AD, p 58)

- "A private madhouse can be defined as a privately owned establishment for the reception and care of insane persons, conducted as a business proposition for the personal profit of the proprietor or proprietors. The history of such establishments in England and Wales can be traced for a period of over three and a half centuries, from the early seventeenth century up to the present day. In the course of their lifespan these institutions were referred to by a variety of terms, ranging from `houses for lunatics', 'madhouses', 'private madhouses', 'private licensed houses' to 'private asylums' and finally, the `mental nursing homes' of the present century. Other types of institutions for the insane were referred to only rarely as 'mad-houses'." (The Trade in Lunacy, William Ll. Parry-Jones, 1972 AD, p1)

- "Most eighteenth-century madhouses were quite small, often containing fewer than ten inmates. Created in accordance with no central scheme or plan, and subject to virtually no legal regulation or restraint, they were, as one would expect, extremely diverse in their orientations and operations. Few were purpose-built, partly because it was obviously cheaper to adapt existing buildings to the purpose, but also because little connection was seen in this period between the characteristics of the physical space within which lunatics were confined and the possibilities of curing them." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 21)

- "The person who was recognized as insane—that is, the person whose actions were obviously a danger to himself or to others—had no protection in law. If he lived in or near London, he might be sent to Bethlem or 'Bedlam', the only institution of any public standing which dealt with the mentally abnormal. If he were wealthy, he might be sent by his relatives to one of the small private madhouses which combined high fees with a pledge of absolute secrecy, or confined alone with an attendant. If he were poor, he might be kept by his family in whatever conditions they chose, or sent to the workhouse or prison for greater security; but whether he lived in London, or in a small and remote village, whether he was rich or poor, he was almost certain to be confined, neglected, and intimidated, if not treated with open cruelty." (A history of the mental health services, Kathleen Jones, 1972 AD, p3)

J. The rise of psychiatry motivated by social control:

- Psychiatric Historians almost always paint a picture of their own industry as scientific progress and selfless altruistic care of the sick and helpless. In fact this image of how institutional psychiatry arose is pure lies. In fact, psychiatric committal into privately funded mad houses for the rich, and later publicly funded asylums for the poor was a form of pure social control of the annoying, unwanted.

- "Very early on in the history of the asylum, it became apparent that its primary value to the community was as a handy place to which to consign the disturbing, the vaguely menacing, the unwanted, and the useless — those potentially and actually troublesome people who posed threats to the social order and to the business of daily living which were not readily subject to control by the legal system." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 353)

- "The direction taken by lunacy reform in the nineteenth century is thus presented as at once inevitable and basically benign — both in intent and in consequences — and the whole process crudely reduced to a simplistic equation: humanitarianism + science + government inspection = the success of what David Roberts terms 'the great nineteenth-century movement for a more humane and intelligent treatment of the insane'. In this and subsequent chapters, I shall endeavour to show that almost all aspects of this purported 'explanation' are false, or provide a grossly distorted and misleading picture of what lunacy reform was all about. ... It is time to transfer our attention away from the rhetoric of intentions and to consider instead what a more searching examination of the historical record reveals about the establishment and operation of the new apparatus for the social control of the mad." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 2)

- The importance of the asylum lies in the fact that it makes available a culturally legitimate alternative, for both the community as a whole and the separate families which make it up, to keeping the intolerable individual in the family. The very existence of the institution not only provides a means of dispensing with all sorts of disorderly, disturbing, and disruptive individuals; it also, by offering another means of coping, affects the degree to which people are prepared to put up with those who persistently create havoc, discord, and disarray, as well as with those whose extreme helplessness and dependency creates extraordinary burdens for others. Thus I would argue that the asylum inevitably operated to reduce family and community tolerance (or, to put it the other way round, to expand the notion of the intolerable), to a degree which varied with how grandiose and well accepted the helping claims of those who ran it were. In so doing, it simultaneously induced a wider conception of the nature of insanity." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 352)

Summary:

- From the beginning of time down to about 1650 AD, the insane were viewed on the basis of their behaviours, not some diagnosis or label. Since the insane chose to be lazy and become dependant, make work and trouble for others, act in ways that others find annoying and offensive, and generally disrupt the peace of organized communities, they were viewed as sinners who refused to obey the gospel or criminals who broke civil laws. The insane were not viewed as a separate class of lazy sinful beggars who needed medical help. Rather they were viewed just like all other poor beggars. Medical doctors had nothing to offer the insane. Church ministers were seen as the top experts to consult when you needed to modify the sinful (insane) behaviours of a relative.

- The history of psychiatric committal, has its origin in removing people whose behaviour choices are on the extreme end of the bell curve of human behaviour and sweeping their "dirt" out of sight and putting them in jails of social control called asylums.

- "I am also against involuntary or coercive treatment on ethical, therapeutic, and scientific grounds. I believe it's wrong to lock up people "for their own good." It also doesn't help. After several hundred years of coercive psychiatry, there is not a single study to indicate that involuntary hospitalization helps patients. Instead of empowering people, forced treatment encourages helplessness and breeds resentment." (The Heart of Being Helpful, Peter Breggin, 1997 AD. p 171)

- The entire process began when rich propertied families paid ministers monthly cash to "institutionalize" their insane in a mad house owned and operated by preachers. It was not altruism that motivated these families to send their insane to a mad house, it was selfish relief of the trouble and embarrassment the insane caused the family on a daily basis. It was not scientific progress in action, it was a parallel penal system that jailed the lazy, uncontrollable and misbehaving family member. The poor could afford no luxury to pay out their own pockets, for another to hold their insane family members in jail for years. It was not medicine, but a new system of social control that legally swept unwanted street beggars from fine British upper class streets. The insane have always chosen to live a life that others find annoying, offensive and cause other trouble, money, work and dependency. Committing the insane to a mad house or public asylum was pure social control.

- "Warehouses of the Unwanted: I have suggested that asylums were largely receptacles for the confinement of the impossible, the inconvenient, and the inept. The comments of the asylum superintendents and the Lunacy Commissioners on the character of asylum inmates provide abundant support for this view. From the moment most asylums opened, they functioned as museums for the collection of the unwanted." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 370)

- "Asylums became a dumping ground for a heterogeneous mass of physical and mental wrecks" — chronic alcoholics afflicted with delirium tremens or, with permanently pickled brains, reduced to a state of dementia; epileptics; tertiary syphilitics; consumptives in the throes of terminal delirium; cases of organic brain damage; diabetics; victims of lead or other forms of heavy metal poisoning; the malnourished; the simple-minded;'' women exhausted and depressed by the perpetual round of pregnancy and childbirth; and those poor worn-out souls who had simply given up the struggle for existence." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 373)

- Since insanity is a behaviour choice and not a disease, it is clear that the medieval societies were as well equipped to evaluate the cause and solution to insanity. They looked at how a person acted in sinful ways and attempted to get the person to repent of this insane behaviour through shame and threats of eternal damnation in hell. Often society took punitive actions against the sinful and disruptive actions of the insane.

- Today, we need to refocus how we view the insane. We, like the medieval peoples, must ignore any diagnosis of a psychiatrist, and do a checklist inventory of the sinful behaviours of the insane.

- Insanity is a behaviour, not a disease. Those who behave in socially unacceptable ways, must be tolerated as objects of shame. Those who break the law must be arrested, tried and only then can their personal freedom be suspended in a jail, not an asylum.

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Send us your story about your experience with modern Psychiatry