Herodotus 484 - 424 BC (Flat Earth Greek Geographer & Historian)

"And I laugh to see how many have before now drawn maps of the world, not one of them reasonably; for they draw the world as round as if fashioned by compasses, encircled by the Ocean river, and Asia and Europe of a like extent. For myself, I will in a few words indicate the extent of the two, and how each should be drawn." (Herodotus, Hist. 4.36.2)

Introduction:

- Herodotus was a Greek wrote his geographic histories around 484-424 BC.

- Herodotus is called the "Father of History" being one of the oldest known geographers.

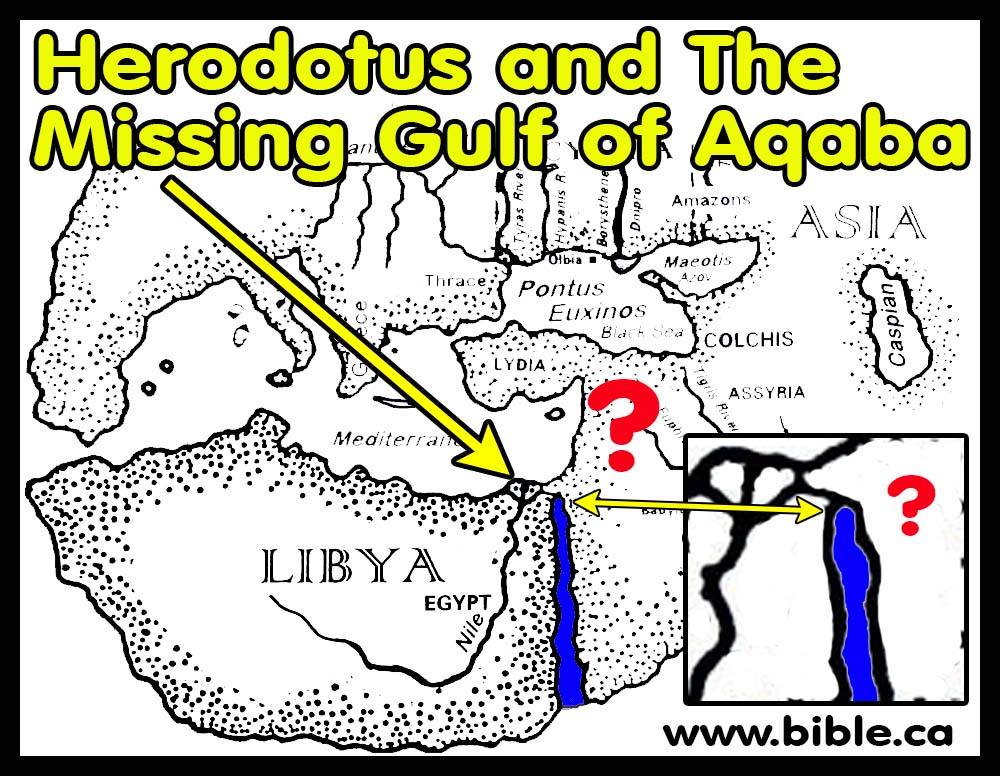

- Herodotus believed the earth was flat, had no concept of the Gulf of Aqaba and made a lot of major mistakes.

- Herodotus' fabricated a prehistoric "GHOST GULF" that leads from the Gulf of Suez to the Mediterranean near Alexandria (2.11.3).

- Herodotus tells us that his geography is based upon a secondhand report from another and not firsthand experience:

- "Thus I give credit to those from whom I received this account of Egypt" (2:12)

- "Concerning the nature of the river [Nile], I was not able to gain any information either from the priests or from others." (2:19)

- Herodotus understood that Arabia proper, "the nation" was nowhere near Egypt:

- "Again, Arabia is the most distant to the south of all inhabited countries: and this is the only country which produces frankincense and myrrh and casia and cinnamon and gum-mastich. All these except myrrh are difficult for the Arabians to get." (Herodotus, Hist. 3.107.1)

- "On this peninsula live thirty nations. This is the first peninsula. But the second, beginning with Persia, stretches to the Red Sea, and is Persian land; and next, the neighboring land of Assyria; and after Assyria, Arabia; this peninsula ends (not truly but only by common consent) at the Arabian Gulf, to which Darius brought a canal from the Nile." (Hdt., Hist. 4.38.2–39.1)

- Herodotus never describes the Sinai Peninsula as Arabia.

- Both Herodotus and Strabo defined ancient Goshen as Arabia but it did not extend east into the Sinai Peninsula. Strabo describes Goshen as between the Nile and the Gulf of Suez. Strabo does not say that Goshen is all the land east of the Nile to Judea, but marks the eastern boundary of Goshen at the Gulf of Suez. This follows the translators of the Septuagint in 280 BC who also called ancient Goshen, “Arabia”. This is because of the large population of Arabs who lived there. Many major cities today have large populations of Chinese called “Chinatown”, but it is understood to be the USA, not China. Likewise, Goshen was called Arabia in the same sense of “Arabtown”.

- The Hebrews living in Goshen during the 430-year captivity controlled the final caravan terminal at the end of the Philistine highway that went up the coast through Gaza and Tyre. The Arabs had moved into ancient Goshen to control not only the caravan routes themselves, but also the end terminals were goods would be unloaded from the camels. There were a series of seaports also occupied by the Arabs south of Gaza that included Arish. The Sinai was not considered Arabia merely because the Arabs controlled the final shipping port at Arish. The geographic proximity of Goshen allowed the Arabs to control both the Philistine coastal route, but any goods entering Egypt at the seaport of the Gulf of Suez.

- “The country between the Nile and the Arabian Gulf [Suez] is Arabia, and at its extremity is situated Pelusium.” (Strabo, Geography 17.1.21)

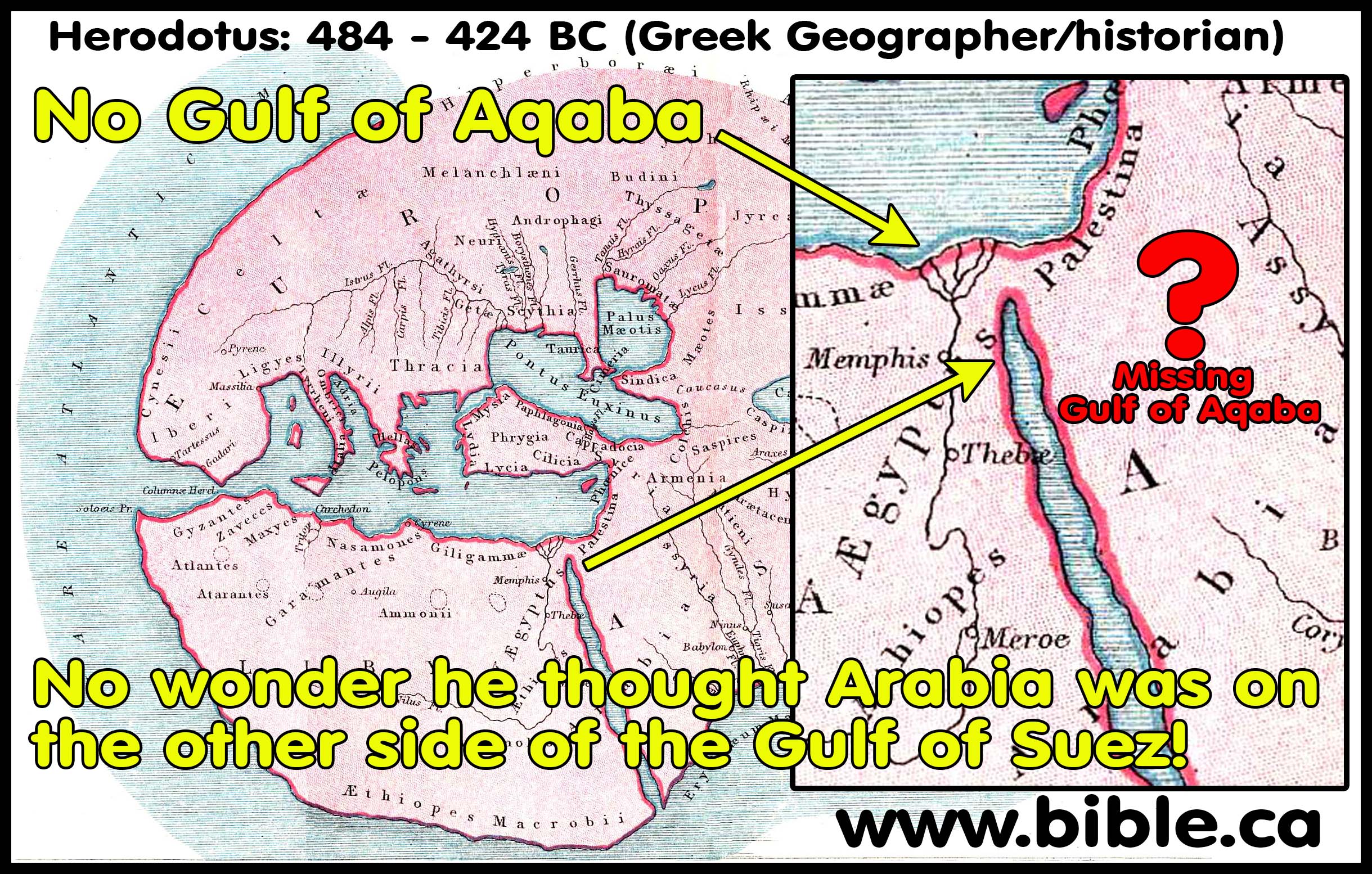

- Although we do not have any actual maps of Herodotus, people have gone to great lengths to create maps based directly on his writings. Below are a few examples. Looking at these modern reconstructions, we immediately notice two glaring problems with his geography that modern cartographers accurately drew.

- First the Red sea is a single finger of water that does not split into the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba.

- Second, there is no reference to Israel because he wrote during the Babylonian captivity and shortly thereafter. Herodotus describes the non-Hebrew people living in Canaan as “Syrians of Palestine”. (Herodotus, Hist. 2.104.3)

- We have supplied three maps based directly upon the writings of a Greek geographer and historian named Herodotus who lived in 450 BC.

- Like Hesiod and Hecataeus his predecessors, he possessed a shallow concept of Israel and has a vague understanding of the Red sea and wrongly viewed it at as a single finger of water.

- Apart from the Bible's clear references to Arabia as a geographic place in 1000 BC (2 Chronicles 9:14) Herodotus is the oldest secular historian who records the region of Arabia.

- Herodotus calls the Red Sea by the colour RED not the sea of Reeds:

- "there is a gulf extending inland from the sea called Red" (Herodotus, Hist. 2.11.1)

- No ancient author ever called any freshwater lake a "Sea of Reeds". Those who say so are perpetuating a fiction to prop up wrong and failing exodus routes at or near the Bitter lakes.

- The Holy Spirit in the New Testament used the same Greek “Red Sea” as the Herodotus and the Septuagint.

- Herodotus also discusses how God destroyed Sennacherib's army confirming the text of 2 Kings 19:35-36.

- Although he wrote his six books in 450 BC, the earliest actual manuscripts of Herodotus are dated 900 AD.

- That means there is a span of 1350 years between when the book was written and the earliest actual hard copies that are extant.

- There are 8 different manuscripts of Herodotus, the oldest being dated from 900 AD.

- We need to remember that the manuscripts of Herodotus' history likely contain changes as do other ancient works.

- Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote, "On the Erythraean Sea" in 169 BC, has been reconstructed from three other ancient authors: Diodorus (49 BC), Strabo (15 AD), Photius (897 AD). The original script of Agatharchides, often has three widely varying readings or "fragments". This is instructive because Photius, who lived in 900 AD (the same time as the oldest manuscript of Herodotus) greatly changed and embellished with his own comments of Agatharchides words when compared to the older versions of Diodorus and Strabo. None of the three agree and contain many differences.

- This contrasts with the Bible, where we have a complete copy from 325AD and over 50,000 manuscripts. The variation between all the manuscripts is very slight.

I. Herodotus had no idea "GULF OF AQABA" even existed:

II. Herodotus' prehistoric "GHOST GULF":

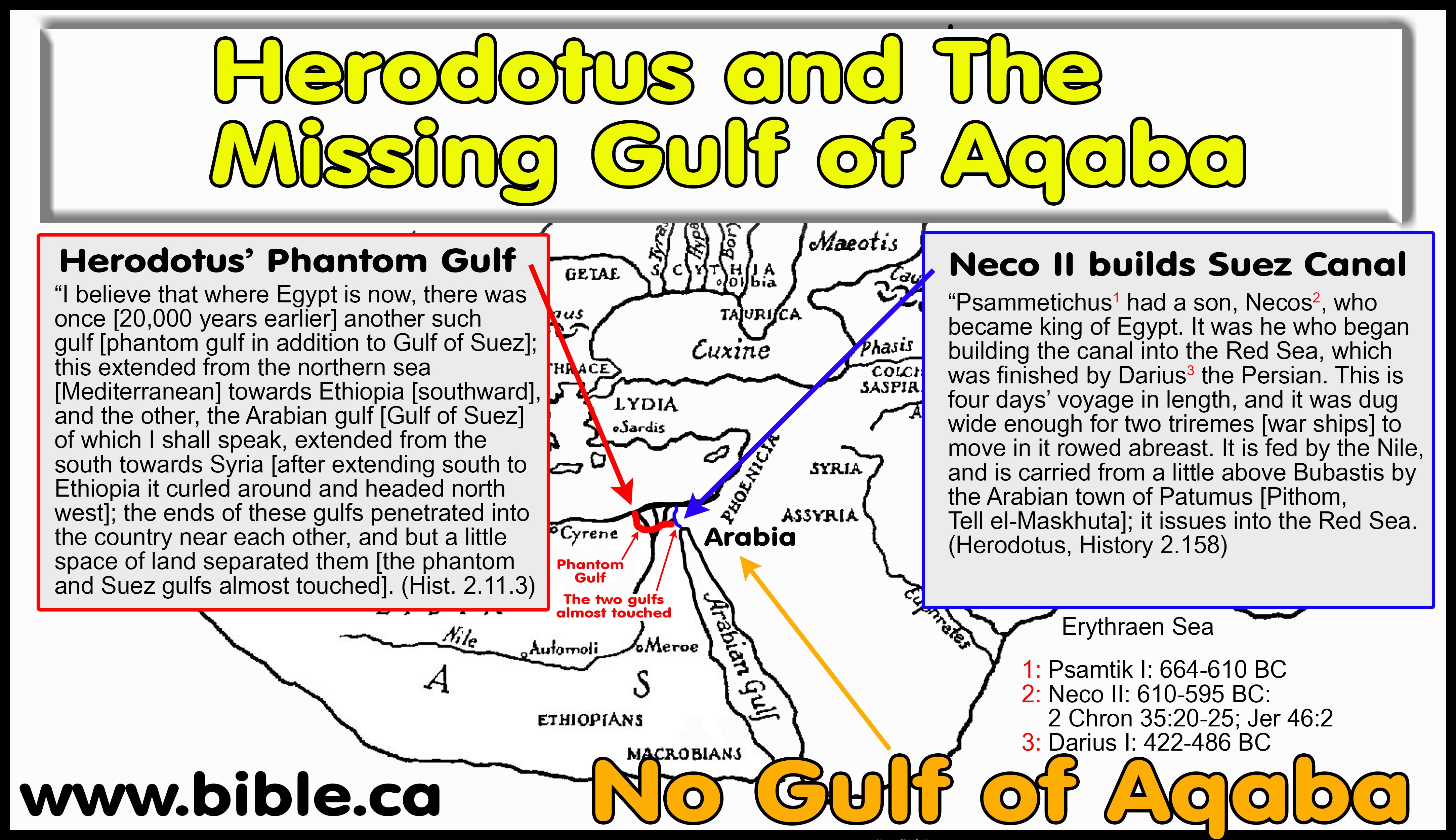

- Herodotus had no idea the Gulf of Aqaba existed but describes his prehistoric "phantom gulf":

- "For of the rivers that brought down the stuff to make these lands, there is none worthy to be compared for greatness with even one of the mouths of the Nile, and the Nile has five mouths. [3] There are also other rivers, not so great as the Nile, that have had great effects; I could rehearse their names, but principal among them is the Achelous, which, flowing through Acarnania and emptying into the sea, has already made half of the Echinades Islands mainland. [11] [1] Now in Arabia, not far from Egypt, there is a gulf extending inland from the sea called Red, whose length and width are such as I shall show: [2] in length, from its inner end out to the wide sea, it is a forty days’ voyage for a ship rowed by oars; and in breadth, it is half a day’s voyage at the widest. Every day the tides ebb and flow in it. [3] [Herodotus describes his 20,000 years earlier PREHISTORIC PHANTOM GULF]: I believe that where Egypt is now, there was once another such gulf; this extended from the northern sea towards Aethiopia [Mediterranean south to Ethiopia], and the other, the Arabian gulf [Gulf of Suez] of which I shall speak, extended from the south towards Syria [after extending south to Ethiopia it curled around and headed north west]; the ends of these gulfs penetrated into the country near each other, and but a little space of land separated them [the phantom and Suez gulfs almost touched]. [4] Now, if the Nile inclined to direct its current into this Arabian gulf, why should the latter not be silted up by it inside of twenty thousand years? In fact, I expect that it would be silted up inside of ten thousand years. Is it to be doubted, then, that in the ages before my birth a gulf even much greater than this should have been silted up by a river so great and so busy? [12] [1] As for Egypt, then, I credit those who say it, and myself very much believe it to be the case; for I have seen that Egypt projects into the sea beyond the neighboring land, and shells are exposed to view on the mountains, and things are coated with salt, so that even the pyramids show it, and the only sandy mountain in Egypt is that which is above Memphis; [2] besides, Egypt is like neither the neighboring land of Arabia nor Libya, not even like Syria (for Syrians inhabit the seaboard of Arabia); it is a land of black and crumbling earth, as if it were alluvial deposit carried down the river from Aethiopia; [3] but we know that the soil of Libya is redder and somewhat sandy, and Arabia and Syria are lands of clay and stones." (Herodotus, Hist. 2.10.2-12.3)

- Herodotus speculates that geologically, in some ancient time (20,000 years ago), there was a second Gulf that started on the Mediterranean and extended south towards Ethopia, then circled through the Nile Delta travelling northwest to almost touch the Gulf of Suez.

- This "ghost gulf" as we call it is known to be geologically false and he was totally wrong.

- Some people wrongly think the ghost gulf that almost touches the Gulf of Suez describes the Gulf of Suez touching the Gulf of Aqaba.

- "the two gulfs ran into the land so as almost to meet each other, and left between them only a very narrow tract of country" (2:11).

- One of these two Gulfs was the Gulf of Suez and the other was the Ghost gulf to the west and they came together and almost touched.

- Some people fail to notice this is ghost gulf (which if it did exist in some distant time in the past was west of the Gulf of Suez)

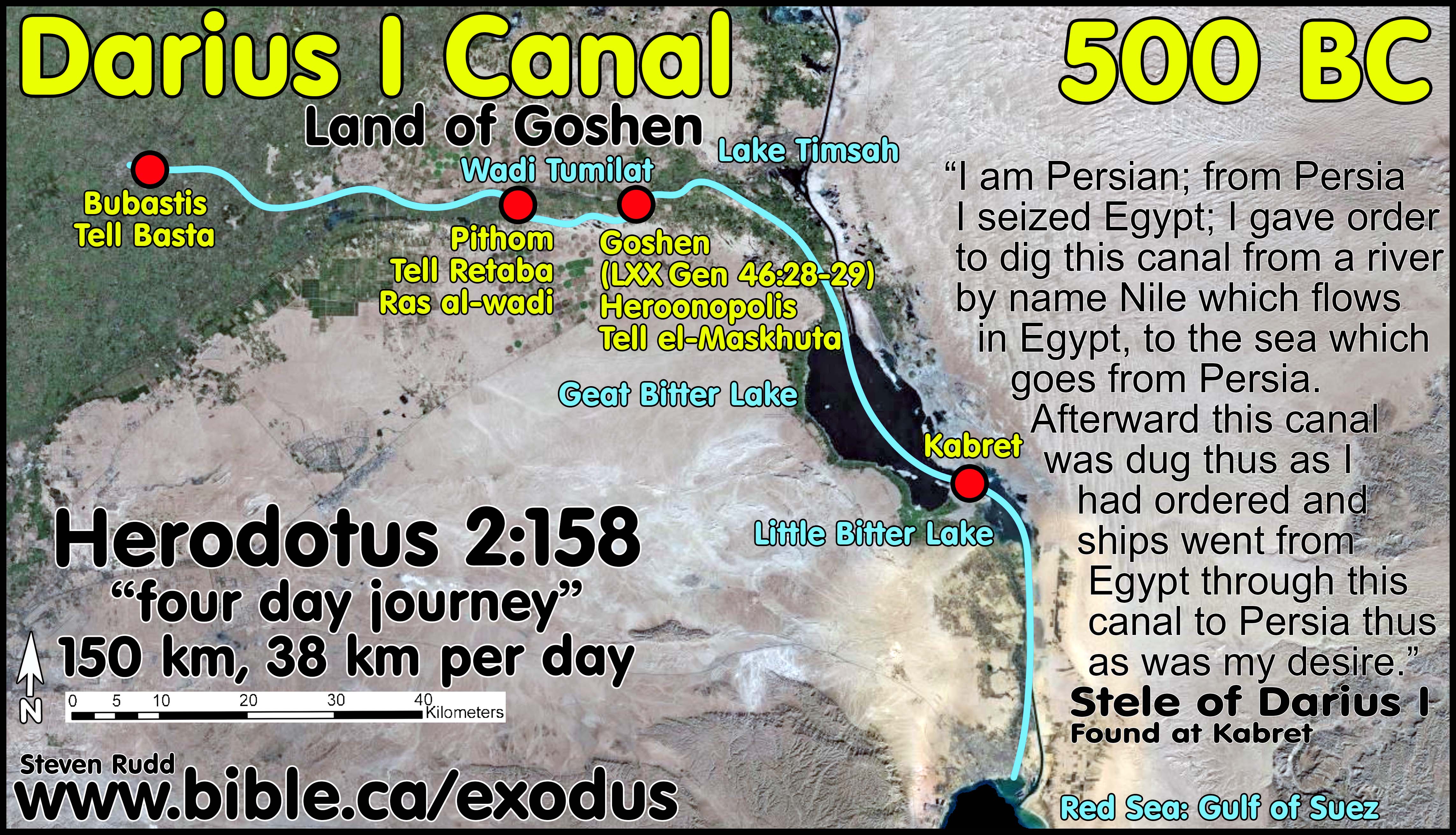

III. The Suez Canal:

1. Summary:

a. The first canal was dug under the reign of Senausret III, Pharao of Egypt (1887-1849 BC) linking the Mediterranean Sea in the north with the Red sea in the south via the river Nile and its branches.

b. The Canal often abandoned to silting and was successfully reopened to navigation by Sity I (1310 BC), Necho II (610 BC), Persian King Darius (522 BC), Polemy II (285 BC), Emperor Trajan (117 AD) and Amro Ibn Elass (640 AD), following the Islamic conquest.

c. Although there are conflicting reports of whether Darius I completed the canal from Bubastis to the Gulf of Suez, Herodotus’ report, coupled with direct archaeological evidence proves he indeed completed it and it was in full operation in his lifetime.

d. The Persian cuneiform text of the stela found at Kabret reads: “Saith Darius the King: I am a Persian; from Persia I seized Egypt; I gave order to dig this canal from a river by the name Nile which flows in Egypt, to the sea which goes from Persia. Afterward this canal was dug thus as I had ordered, and ships went from Egypt through this canal to Persia.”

e. Herodotus 2:158 says it took 4 days to travel the full length of the 150 km canal built by Darius I around 500 BC. This produces a daily travel rate of 38 km per day. The journey is by foot not by ship, because a trireme, with three sets of rowers could travel the entire 150 km in less than a day at speeds of 22 km per hour.

f. "This canal ran from near Tel Basta (Bubastis) apparently to Suez. Inscriptions recording Darius’ construction of it have been found in the neighborhood." (Herodotus, translators footnote, History 2.158.1–159.2)

2. The canal by Darius I was 4 Days journey by foot not by ship:

a. Since it was a canal, the four days that Herodotus said it took to making the 150 km trip from Bubastis to the Gulf of Suez could be by ship as opposed to on foot.

b. Herodotus specifically says that two triremes could make the trip side by side, indicating the width of the canal. These ships were 120 feet long, had a crew of over 200 and was powered by three sets of rowers, one above the other.

c. A trireme commonly travelled 213 to 270 km in a single day with speeds up to 22 km per hour.

d. We can conclude that Herodotus was referring to 4 days by foot not by ship, because a trireme could easily navigate the entire 150 km canal in less than one day.

e. Paul applied the metaphor of being an “under-rower” to full time ministers of Christ in 1 Corinthians 4:1. Gospel preachers therefore are not only servants of God, they are the ones who are the lowest rank, rowing at the bottom of the ship, below the two higher sets of rowers, in the hot, humid, smelly and dark conditions in the hull of the ship.

f. “By the sixth century b.c. the Greeks had developed the trireme for its naval force. The trireme required an intricate system of three banks of oars: the thranites, oarsmen at the top level, worked their oars through an outrigger; the zygites pulled their oars either over a gunwale or through oarports; and the thalamites worked at the lowest level no more than eighteen inches above the waterline. The captains were known as trierarchs. The kubernētēs (or pilot) steered the ship from the stern. At the bow was the prorates who served as the eyes of the ship. The keleustēs called out the beat of the oarsmen accompanied by the aulētēs, playing on his flute. The remains of ship sheds in the Zea harbor of Athens averaged 37 meters (121 feet, 5 inches), with a further extension underwater, indicating that the ships were at least this long, perhaps up to 140 feet. They measured about 18 to 20 feet wide, with a draught of 4 to 6 feet. The oars would have extended an additional 14 feet on each side. Each trireme carried a crew of about 200 with 10 to 30 epibatai or marines, and a few archers who were recruited from Crete. The main tactic would be to attempt to ram the enemy ship with the embolos or bronze ram at the prow of the ship. Triremes could make 115 to 146 nautical miles a day [213 to 270 km per day], and could reach a maximum speed of 11 to 12 knots (about 14 miles) per hour [22 km per hour]. Recently a modern replica of an ancient trireme was made by the Greeks under the direction of British scholars John S. Morrison and John F. Coates. After some practice, a volunteer crew of 140 men and 40 women from England was able to reach top speeds of 9 to 10 knots for short bursts. At Salamis Aeschylus reported that the Greek fleet numbered 300 (or possibly 310). The largest number (200) was provided by Athens. Corinth provided the next largest number (40). Aegina, Megara, and Sparta provided the remainder.” (Persia and the Bible, Edwin M. Yamauchi, The Greek Army and Navy, p199, 1996 AD)

3. Ancient literary sources:

a. “Psammetichus [Psamtik I: 664-610 BC] had a son, Necos [Neco II: 610-595 BC: 2 Chron 35:20-25; Jer 46:2], who became king of Egypt. It was he who began building the canal into the Red Sea (around 600 BC), which was finished by Darius the Persian [Darius I: 422-486 BC]. This is four days voyage in length, and it was dug wide enough for two triremes to move in it rowed abreast. [2] It is fed by the Nile and is carried from a little above Bubastis by the Arabian town of Patumus [Pithom, Tell el-Maskhuta]; it issues into the Red Sea. Digging began in the part of the Egyptian plain nearest to Arabia; the mountains that extend to Memphis (the mountains where the stone quarries are) come close to this plain; [3] the canal is led along the foothills of these mountains in a long reach from west to east; passing then into a ravine, it bears southward out of the hill country towards the Arabian Gulf. [4] Now the shortest and most direct passage from the northern to the southern or Red Sea is from the Casian promontory, the boundary between Egypt and Syria, to the Arabian Gulf, and this is a distance of one hundred and twenty five miles, neither more nor less; [5] this is the most direct route, but the canal is far longer, inasmuch as it is more crooked. In Necos’ reign, a hundred and twenty thousand Egyptians died digging it. Necos stopped work, stayed by a prophetic utterance that he was toiling beforehand for the barbarian. The Egyptians call all men of other languages barbarians. [159] [1] Necos, then, stopped work on the canal and engaged in preparations for war; some of his ships of war were built on the northern sea, and some in the Arabian Gulf, by the Red Sea coast: the winches for landing these can still be seen. [2] He used these ships when needed, and with his land army met and defeated the Syrians at Magdolus, taking the great Syrian city of Cadytis after the battle. (Herodotus, History 2.158.1–159.2)

b. “There are also other mouths, built by the hand of man, about which there is no special need to write. At each mouth is a walled city, which is divided into two parts by the river and provided on each side of the mouth with pontoon bridges and guard-houses at suitable points. From the Pelusiac mouth there is an artificial canal to the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea. 9 The first to undertake the construction of this was Necho the son of Psammetichus, and after him Darius the Persian made progress with the work for a time but finally left it unfinished; 10 for he was informed by certain persons that if he dug through the neck of land he would be responsible for the submergence of Egypt, for they pointed out to him that the Red Sea was higher than Egypt. 11 At a later time the second Ptolemy completed it and in the most suitable spot constructed an ingenious kind of a lock. This he opened, whenever he wished to pass through, and quickly closed again, a contrivance which usage proved to be highly successful. 12 The river which flows through this canal is named Ptolemy, after the builder of it, and has at its mouth the city called Arsinoë.” (Diodorus Siculus, Historical Library I.33.8-12, 30 BC)

c. “This is clear to anyone who looks at the country itself, and further proof is afforded by the facts about the Red Sea. One of the kings tried to dig a canal to it. (For it would be of no little advantage to them if this whole region was accessible to navigation: Sesostris is said to be the first of the ancient kings to have attempted the work.) It was, however, found that the sea was higher than the land: and so Sesostris first and Dareius after him gave up digging the canal for fear the water of the river should be ruined by an admixture of sea-water.” (Aristotle, Meteorology 1.14.25)

d. “There is another canal also, which empties itself into the Red Sea, or Arabian Gulf, near the city Arsinoë (Suez), which some call Cleopatris. It flows through the Bitter Lakes, as they are called, which were bitter formerly, but when the above-mentioned canal was cut, the bitter quality was altered by their junction with the river, and at present they contain excellent fish, and abound with aquatic birds. The canal was first cut by Sesostris before the Trojan times, but according to other writers, by the son of Psammitichus, who only began the work, and afterwards died; lastly, Darius the First succeeded to the completion of the undertaking, but he desisted from continuing the work, when it was nearly finished, influenced by an erroneous opinion that the level of the Red Sea was higher than Egypt, and that if the whole of the intervening isthmus were cut through, the country would be overflowed by the sea. The Ptolemaic kings however did cut through it, and placed locks upon the canal, so that they sailed, when they pleased, without obstruction into the outer sea, and back again [into the canal].” (Strabo, Geography 17.1.25)

e. “This was contemplated first of all by Sesostris, king of Egypt, afterwards by Darius, king of the Persians, and still later by Ptolemy II., who also made a canal, one hundred feet in width and forty deep, extending a distance of thirty-seven miles and a half, as far as the Bitter Springs [from Bubastis to the eastern shore of Lake Timsah]. He was deterred from proceeding any further with this work by apprehensions of an inundation, upon finding that the Red Sea was three cubits higher than the land in the interior of Egypt. Some writers, however, do not allege this as the cause, but say that his reason was, a fear lest, in consequence of introducing the sea, the water of the Nile might be spoilt, that being the only source from which the Egyptians obtain water for drinking.” (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 6.33.165)

4. Modern sources:

a. “When Darius's workmen set out to dig his canal, they did not have to start from scratch. According to Herodotus, they completed the project started by Necho II, who was unable to finish it because he lost so many workmen in the course of his excavations. This information reinforces the importance of the description given by Herodotus for the direction of the Necho-Darius canal. It left the Nile a little south of Bubastis, which would put the commencement of this canal at the western entrance to the Wadi Tumilat. It ran eastward and eventually turned south to run into the Arabian Gulf, the modern Gulf of Suez. Since this canal entered the Wadi Tumilat in the west, it should have left it in the east, which would connect it with Lake Timsah, the body of water lying most directly opposite that exit. From Lake Timsah, this canal must have run south.” (A Date for the Recently Discovered Eastern Canal of Egypt, William H. Shea Source BASOR, No. 226, p32, 1977 AD)

b. “Greek and Roman authors after Herodotus claim that the Achaemenid ruler Darius I (522-486 BC) also attempted a canal, but abandoned the scheme when he too was persuaded that Egypt would be inundated by seawater as a result. In fact, the existence of a completed Persian canal is indicated by the eyewitness account of Herodotus, who visited Egypt some time after 454 BC, and by the discovery in the 19th century AD of four Persian stelae positioned along its route – by Tall al-Maskhūtah, and at Serapeum, Kabrat [Kabret], and Kūbrī – and commemorating its completion8 (Figure 20:2). The relatively well-preserved Persian cuneiform text of the stela found at Kabret reads: “Saith Darius the King: I am a Persian; from Persia I seized Egypt; I gave order to dig this canal from a river by the name Nile which flows in Egypt, to the sea which goes from Persia. Afterward this canal was dug thus as I had ordered, and ships went from Egypt through this canal to Persia.” (Egypt’s Nile-Red Sea canals: chronology, location, seasonality and function, John Philip Cooper, Connected Hinterlands, p197, 2009 AD)

c. “At first we misunderstood the evidence for the Saite period occupation, probably to be dated to the reign of Pharaoh Necho II and to be connected with his early efforts at cutting the canal through to the Red Sea. Greek forms, Phoenician forms, and native Egyptian materials jumble together in the mix one has learned to expect of the “Persian Period.” And so we called it until postseason research revealed similar mixtures in Egyptian mercenary encampments farther north. Present indications are that, despite the canal’s incomplete status, Tell el-Maskhuta (Heroonopolis) served as a functioning port channelling goods to the Red Sea and back again. Phoenicians and Greek soldiers rubbed shoulders with Egyptian merchants and officers, and it is not at all impossible that the merchant forerunners of the looming Persian Empire were already on the scene. Beneath the founding phases of Necho’s city we found no certain traces of occupation. Only the (pre-) Hyksos graves and the much earlier flints give evidence for some yet undefined earlier use of the site.” (Excavations at Tell El Maskhuta = Heroonopolis, Burton MacDonald, Biblical Archaeologist, Vol 43, 1980 AD)

d. “The Canal Inscriptions: Darius had a canal completed between the Nile and the Red Sea. Middle Kingdom inscriptions already referred to a canal dug by the Egyptians between the Pelusiac branch of the Nile and the Red Sea. Recent satellite photos have revealed the location of this early canal. In the Saite period Necho II (610–595) attempted unsuccessfully to dig another canal, no doubt because the earlier canal had become unusable. According to Herodotus (2.158): It was he [Necho] who began the making of the canal into the Red Sea, which was finished by Darius the Persian. This is four days’ voyage in length, and it was dug wide enough for two triremes to move in it rowed abreast. The canal extended some 50 miles, and was perhaps 45 meters (148 feet) wide and 3 meters (10 feet) deep. The project took about a dozen years to complete. Herodotus’s report has been directly confirmed by the discovery of four fragmentary stelae of red granite inscribed in cuneiform and hieroglyphs, which commemorated the digging of the canal by Darius. These include: the Maskhuta stele found in 1864; the so-called Serapeum stele found by Napoleon’s soldiers between Lake Timsa and the Bitter Lakes in 1799; the Shallūfa stele discovered twenty miles north of Suez by Charles de Lesseps, brother of the engineer who built the modern Suez Canal (this is the best-preserved text); and the Kubri or Suez stele, found about twenty miles north of Suez and first published in 1908. Because these inscriptions proclaim Darius as the son of Neith, one may consider Udjahorresnet, the priest of Neith who had helped Cambyses, as the Egyptian advisor who helped compose these texts. According to the OP text on these stelae Darius proclaimed: I am Persian; from Persia I seized Egypt; I gave order to dig this canal from a river by name Nile which flows in Egypt, to the sea which goes from Persia. Afterward this canal was dug thus as I had ordered and ships went from Egypt through this canal to Persia thus as was my desire. It was not true, of course, that Darius was the first to conquer Egypt; here he is claiming credit for that which was accomplished by his predecessor. The corresponding Egyptian text speaks of “twenty-four ships with tribute for Persia.” Darius’s purpose in completing the canal was to facilitate traffic between Egypt through the Red Sea, around the Arabian peninsula, and into the Persian Gulf.” (Persia and the Bible, Edwin M. Yamauchi, Darius, p152, 1996 AD)

e. “At Tell el-Maskhuta, along the Wadi Thumilat canal connecting Memphis in the eastern Delta to the Suez canal and Red Sea, a sanctuary was found with silver bowls inscribed in Aramaic, three of which were votive offerings to Han-ʾIlat (the Arabian goddess Allat) by Arabs including “Qainu son of Geshem, King of Qedar,” whose father is known from the OT and other sources. A hoard of thousands of Attic tetradrachma was also discovered at the shrine, reflecting the prosperity of trade flowing through this vital artery to the Nile from the Red Sea.” (New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, David F. Graf, Arab, Arabian, Arabia, Persian period, Vol 1, p217, 2009 AD)

f. “Darius united the latter river with the Red Sea by a canal, the partly obliterated inscription commemorating which may perhaps be thus restored and rendered: “I am a Persian; with Persia I seized Egypt. I commanded to dig this canal from the river named the Nile [Pirāva], which flows through Egypt, to this sea which comes from Persia. Then this canal was dug, according as I commanded. And I said, ‛Come ye from the Nile through this canal to Persia.’”” (ISBE, Darius, Vol 4, p2336)

g. “Darius [Darius I: 422-486 BC] undertook an extensive campaign of public works in Egypt, including completion of the precursor of the Suez Canal.” (Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, Darius I)

IV. Herodotus ignores Israel because they were in Babylon: "Syrians of Palestine"

- Herodotus lived and wrote around 484 BC when Israel had been in Babylonian Captivity and were reestablishing themselves.

- 42,360 Jews first returned from Captivity in 533 BC (Ezra 2:64)

- The temple was completed in Jerusalem in 515 BC.

- The walls of Jerusalem were completed in 445 BC under Nehemiah.

- Herodotus' references to Palestine:

- "From there they marched against Egypt: and when they were in the part of Syria called Palestine, Psammetichus king of Egypt met them and persuaded them with gifts and prayers to come no further." (Herodotus, Hist. 1.105.1)

- "The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine acknowledge that they learned the custom from the Egyptians" (Herodotus, Hist. 2.104.3)

- "As to the pillars that Sesostris, king of Egypt, set up in the countries, most of them are no longer to be seen. But I myself saw them in the Palestine district of Syria, with the aforesaid writing and the women’s private parts on them." (Herodotus, Hist. 2.106.1)

- "Now the only apparent way of entry into Egypt is this. The road runs from Phoenicia as far as the borders of the city of Cadytis [Gaza], which belongs to the so-called Syrians of Palestine. (Herodotus, Hist. 3.5.1–2)

- Herodotus called the land of Israel "Palestine" (ie. Philistines) in 450 BC.

- Herodotus did write of "palaistine" in Greek, however, he was not referring to "palestine".

- The Philistines have an occupational presence in Canaan that dates back to the time of Abraham.

- "Palaistine" referred to the land of the Philistines.

- He wrote of "palaistine syrine"--the Philistines of Syria--which was a limited area near the southwestern coast of Israel.

- History shows that it was Hadrian who renamed the land of Israel "Palestine" [ie. the land of the Philistines] in 135 AD. Hadrian's intent was to wipe out all traces of the Jews. The fact he gave Jerusalem a new name, "Colonia Aelia Capitolina" and the land a new name "Palestine".

- He must have been aware of the Jews, since he says that the inhabitants of "Palaistinê" were circumcised, but he also says that there were other nations as well that circumcised:

- "The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine acknowledge that they learned the custom from the Egyptians, and the Syrians of the valleys of the Thermodon and the Parthenius, as well as their neighbors the Macrones, say that they learned it lately from the Colchians. These are the only nations that circumcise, and it is seen that they do just as the Egyptians. [4] But as to the Egyptians and Ethiopians themselves, I cannot say which nation learned it from the other; for it is evidently a very ancient custom." (Hdt., Hist. 2.104.3–4)

V. Herodotus calls the port city of Arish/Tharu/Rhinocolura, Arabia:

1. Herodotus records how during the Babylonian captivity (605-536 BC) when Israel was vacant from Canaan, both Syrian and the Arabians moved into the coastal areas between Gaza and the Serbonian marsh. In 568 BC, Nebuchadnezzar conquers Egypt. The Jews completed the temple in 515 BC but did not finish the walls of Jerusalem until 445 BC. It was at exactly this time that Herodotus wrote his account and the Arab occupation of these seaports in 450 BC do not reflect the geographic territory of Arabia in the first century. Herodotus believed in a flat earth and did not know the Gulf of Aqaba existed. At the time Herodotus wrote his history, the Jews remained a tiny occupied vassal-state under Persian control down to the time of Alexander the Great in 333 BC. Herodotus understood Arabia proper to be Saudi Arabia but noted that the Arabs controlled a few key Sea ports on the Mediterranean. Herodotus says that this small 50 km coastal strip of Arab controlled seaports was flanked on the western side by 100 km of Syrian controlled land to Pelusium and on the eastern side all the way up the coast to the north. This refutes the fiction that the Sinai Peninsula was considered Arabia by Herodotus because the Arabian controlled seaports were flanked on either side by much large Syrian controlled territories from the Nile to Tyre. This small, isolated 50 km strip of Arab controlled land was not Arabia but the end of their trading routes on the Mediterranean coast. Herodotus notes that the Arabs inhabited the area of ancient Goshen which lay at the end of the ancient coastal trading route that went north to Philistia through Gaza, Tyre and Byblos etc. Herodotus describes how Syrian Gentiles controlled Gaza, but the Arabs controlled the seaports of Raphia and Arish/Tharu/Rhinocolura. These Arab controlled seaports were not considered “Arabia” but end points of the Arab trade routes. They came under the control of Alexander the Great and as Judea reestablished themselves the Arabs lost control of these seaports. Under the Maccabees (100 BC), Arab control had been extinguished in the Sinai Peninsula.

a. “Now the only apparent way of entry into Egypt is this. The road runs from Phoenicia as far as the borders of the city of Cadytis [or Kadytis = Gaza], which belongs to the so-called Syrians of Palestine [Gentiles]. From Cadytis (which, as I judge, is a city not much smaller than Sardis) to the city of Ienysus [Arish= Tharu = Rhinocolura] the seaports belong to the Arabians; then they are Syrian again from Ienysus as far as the Serbonian marsh, beside which the Casian promontory stretches seawards; from this Serbonian marsh, where Typho is supposed to have been hidden, the country is Egypt.” (Herodotus, Hist. 3.5.1–3)

b. “This is the first peninsula. But the second [i.e. land between the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea], beginning with Persia, stretches to the Red Sea, and is Persian land; and next, the neighboring land of Assyria; and after Assyria, Arabia; this peninsula ends (not truly but only by common consent) at the Arabian Gulf, to which Darius brought a canal from the Nile.” (Herodotus 4.39)

c. “The ancient geographers did not usually extend ‘Arabia’ to the Mediterranean, nor does Herodotus himself in iv. 39. He means here that the ends of the trade routes from Arabia to the Mediterranean were under Arabian control (cf. iii. 107 seq. for this spice trade); he writes τοῦ Ἀραβίου, ‘in possession of the Arabian,’ not τῆς Ἁραβίης, For the Arabs of South Palestine as dependent allies (not subjects) of the Persians cf. 88. 1 n.” (A Commentary on Herodotus, W. How, Herodotus 3.5.2, 2000 AD)

- “Herodotus knows nothing of the modern Persian Gulf or of the shape of Arabia. His ‘Assyria’ consists of the basins of the Euphrates and Tigris below Armenia (i. 178. 1 n.), and his ‘Arabia’ includes the southern part of the desert as well as Arabia proper. νόμῳ. … The three nations are Assyria and Arabia with Phoenicia, not with Persia (as Macan); Persia is the base of the ἀκτή, not part of it.” (A Commentary on Herodotus, W. How, Herodotus 4.39, 2000 AD)

VI. Herodotus calls ancient Goshen, Arabia:

- Ancient Goshen was located at the end of the Philistine trade route and by 500 BC had been taken over by a large population of Arabs.

- The Arabians, like the Ishmaelites, controlled all the trade routes and enriched themselves greatly.

- Eventually, the Arabian caravan traders took control of the end ports where the camels were off-loaded.

- Goshen became a strategic location because it served as a shipping hub for both the Philistine route and the Port of Suez.

- Strabo clarifies the geography by limiting the area of Arabia as being west of the Suez Canal and east of the Nile.

- Neither Strabo nor Herodotus defined the Sinai Peninsula as Arabia.

- Arabia in ancient Goshen was a small area with a large population of Arabians who controlled the shipping of goods into Egypt.

- Strabo defines ancient Goshen as Arabia.

- “The country between the Nile and the Arabian Gulf is Arabia, and at its extremity is situated Pelusium.” (Strabo, Geography 17.1.21)

- Strabo describes Goshen as between the Nile and the Gulf of Suez. Strabo does not say that Goshen is all the land east of the Nile to Judea, but marks the eastern boundary of Goshen at the Gulf of Suez. This follows the translators of the Septuagint in 280 BC who also called ancient Goshen, “Arabia”. This is because of the large population of Arabs who lived there. Many major cities today have large populations of Chinese called “Chinatown”, but it is understood to be the USA, not China. Likewise, Goshen was called Arabia in the same sense of “Arabtown”. The Hebrews living in Goshen during the 430-year captivity controlled the final caravan terminal at the end of the Philistine highway that went up the coast through Gaza and Tyre. The Arabs had moved into ancient Goshen to control not only the caravan routes themselves, but also the end terminals were goods would be unloaded from the camels. There were a series of seaports also occupied by the Arabs south of Gaza that included Arish. The Sinai was not considered Arabia because the Arabs controlled the final shipping ports.

- Herodotus speaks of Arabian towns in the Nile Delta in ancient Goshen:

- Pithom is south-east of Tel El-Dab'a (Goshen) inside the Nile Delta of Egypt: "Arabian town of Patumus [Pithom, Tell el-Retaba]" (Herodotus, History 2.158.2)

- Buto is possibly the archeological site of Tell al-Fara'in near Rosetta in the north western Nile delta. "Arabia not far from the town of Buto" (Herodotus, Histories 2.75.1) The Buto Herodotus is speaking of may be a different location altogether. Some place it near Tel El-Dab'a in Goshen. However, Herodotus describes how Buto was one of six Egyptian cult centers where sacrifices were made. It is unclear how Buto in the north western Nile Delta beside Alexandria can be called “in Arabia” but it is certain that Herodotus did not consider this Arabia territory.

- "There is a place in Arabia not far from the town of Buto where I went to learn about the winged serpents. When I arrived there, I saw innumerable bones and backbones of serpents: many heaps of backbones, great and small and even smaller. [2] This place, where the backbones lay scattered, is where a narrow mountain pass opens into a great plain, which adjoins the plain of Egypt. [3] Winged serpents are said to fly from Arabia at the beginning of spring, making for Egypt; but the ibis birds encounter the invaders in this pass and kill them. [4] The Arabians say that the ibis is greatly honored by the Egyptians for this service, and the Egyptians give the same reason for honoring these birds. [76] [1] Now this is the appearance of the ibis. It is all quite black, with the legs of a crane, and a beak sharply hooked, and is as big as a landrail. Such is the appearance of the ibis which fights with the serpents. Those that most associate with men (for there are two kinds of ibis) [2] have the whole head and neck bare of feathers; their plumage is white, except the head and neck and wingtips and tail (these being quite black); the legs and beak of the bird are like those of the other ibis. The serpents are like water-snakes. [3] Their wings are not feathered but very like the wings of a bat. I have now said enough concerning creatures that are sacred. (Hdt., Hist. 2.75.1–76.3)

- “I consider this proved, because the Egyptian ceremonies are manifestly very ancient, and the Greek are of recent origin. [59] [1] The Egyptians hold solemn assemblies not once a year, but often. The principal one of these and the most enthusiastically celebrated is that in honor of Artemis at the town of Bubastis, and the next is that in honor of Isis at Busiris. [2] This town is in the middle of the Egyptian Delta, and there is in it a very great temple of Isis, who is Demeter in the Greek language. [3] The third greatest festival is at Saïs in honor of Athena; the fourth is the festival of the sun at Heliopolis, the fifth of Leto at Buto, and the sixth of Ares at Papremis. [60] [1] When the people are on their way to Bubastis, they go by river, a great number in every boat, men and women together. Some of the women make a noise with rattles, others play flutes all the way, while the rest of the women, and the men, sing and clap their hands. [2] As they travel by river to Bubastis, whenever they come near any other town they bring their boat near the bank; then some of the women do as I have said, while some shout mockery of the women of the town; others dance, and others stand up and lift their skirts. They do this whenever they come alongside any riverside town. [3] But when they have reached Bubastis, they make a festival with great sacrifices, and more wine is drunk at this feast than in the whole year besides. It is customary for men and women (but not children) to assemble there to the number of seven hundred thousand, as the people of the place say.” (Herodotus, Hist. 2.58.1–60.3)

- “When the people go to Heliopolis and Buto, they offer sacrifice only.” (Herodotus, Hist. 2.63.1)

- Herodotus said the Nile flooded Goshen (Arabia):

i. "So said the oracle. Now the Nile, when it overflows, floods not only the Delta, but also the tracts of country on both sides the stream which are thought to belong to Libya and Arabia, in some places reaching to the extent of two days' journey from its banks, in some even exceeding that distance, but in others falling short of it. Concerning the nature of the river, I was not able to gain any information either from the priests or from others." (Herodotus 2:19)

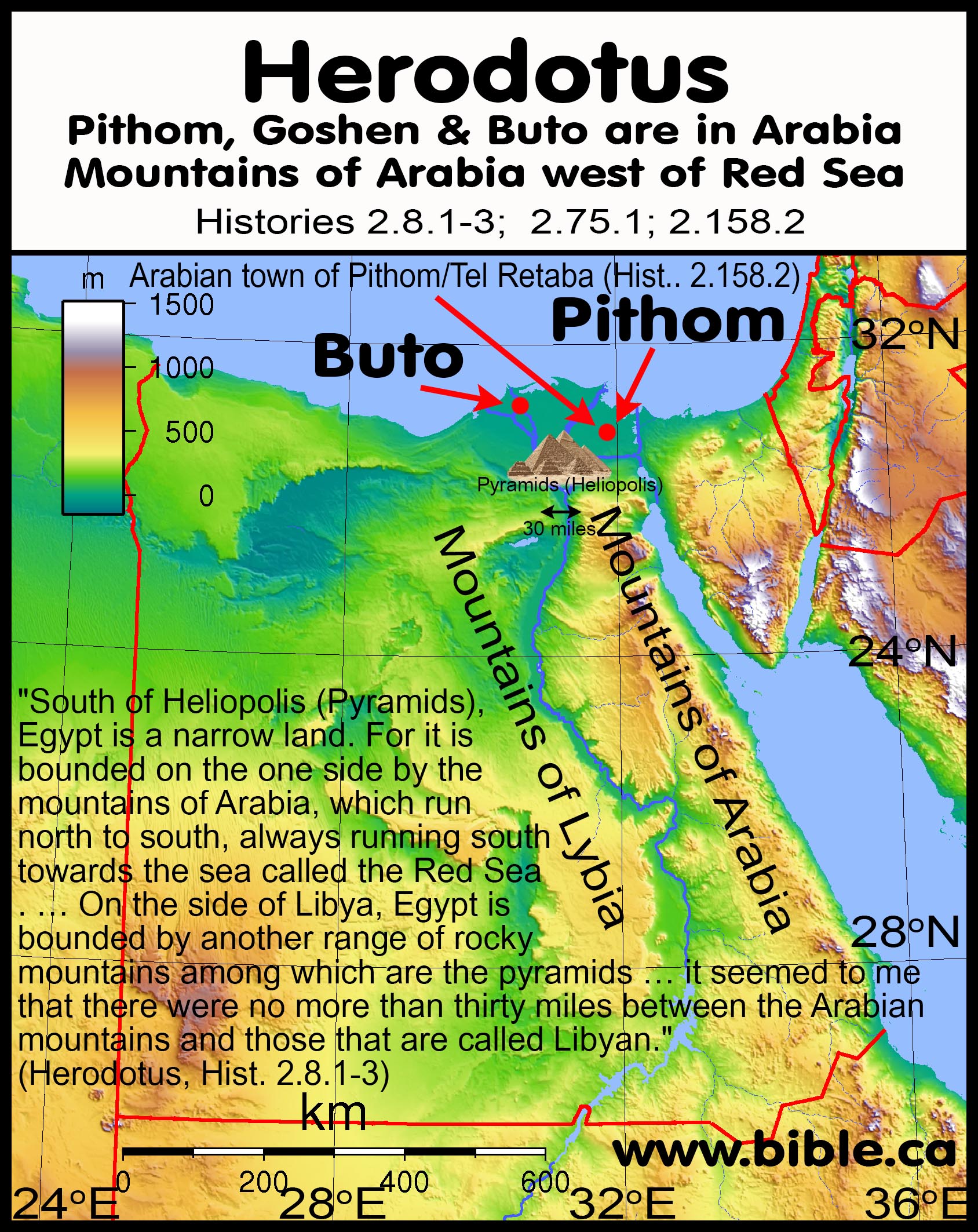

- Herodotus placed the Mountains of Arabia west of the Red Sea (Arabian Gulf). These mountains are not in Arabia they are in Egypt. They are call Arabian mountains because they flank the border with Arabia on the other side of the Red Sea. We all understand that Donald Trump's "Mexican Wall" is on US soil. Even if the Mexicans paid for it after all just like Trump promised! However, we know that the Arabian Troglodytes lived along this seacoast and as “cave dwellers” by definition, may have inhabited the mountains.

- Strabo assigns the territory of the Arabian Troglodytes (Cave Dwellers) on the western coast of the Arabian Gulf beside Egypt and Ethiopia from the Gulf of Aqaba to the south.

- “Perhaps this [last] term is that by which the Greeks anciently designated the Arabs; the etymon of the word certainly strengthens the idea. Many deduce the etymology of the Erembi from ἔραν ἐμαίνειν, (to go into the earth,) which [they say] was altered by the people of a later generation into the more intelligible name of Troglodytes [cave dwellers], by which are intended those Arabs who dwell on that side of the Arabian Gulf next to Egypt and Ethiopia.” (Strabo, Geography 1.2.34)

ii. “The Troglodytica extended along the western side of the Arabian Gulf, from about the 19th degree of latitude to beyond the strait. According to Pliny, vi. c. 34, Sesostris conducted his army as far as the promontory Mossylicus, which I think is Cape Mete of the modern kingdom of Adel. Gossellin.” (Strabo, The Geography of Strabo, H. C. Hamilton, Strabo, Geography 16.4.4 p191, fn 5005, 1903 AD)

- "To some, he assigned the task of dragging stones from the quarries in the Arabian mountains to the Nile; and after the stones were ferried across the river in boats, he organized others to receive and drag them to the mountains called Libyan. [3] They worked in gangs of a hundred thousand men, each gang for three months. For ten years the people wore themselves out building the road over which the stones were dragged, work which was in my opinion not much lighter at all than the building of the pyramid" (Hdt., Hist. 2.124.2-3)

- "Beyond

[to the south] and above Heliopolis (5 km east of the great Pyramids of

Giza), Egypt is a narrow land. For it is bounded

on the one side by the mountains of Arabia, which run north to south,

always running south towards the sea called the Red Sea. In these mountains are the quarries that were

hewn out for making the pyramids at Memphis. This way, then, the

mountains run, and end in the places of which I have spoken; their

greatest width from east to west, as I learned by inquiry, is a two

months’ journey, and their easternmost boundaries yield frankincense. [2]

Such are these mountains. On the side of

Libya, Egypt is bounded by another range of rocky mountains among which

are the pyramids; these are all

covered with sand, and run in the same direction as those Arabian hills

that run southward. [3] Beyond Heliopolis, there is no great distance—in

Egypt, that is: the narrow land has a length of only fourteen days’

journey up the river. Between the aforesaid mountain ranges, the land is

level, and where the plain is narrowest it seemed to me that there were no more than thirty miles between the Arabian mountains

and those that are called Libyan.

Beyond this Egypt is a wide land again. (Herodotus, Hist. 2.8.1-3)

Conclusion:

1. Herodotus knew full well that Arabia proper was nowhere near Egypt. His comments that lead some to put "Arabia in Egypt" are rather simple to explain:

a. "Arabian cities" in the Nile Delta are merely Arab immigrants who formed a majority population in a city inside Egypt. There is a "China Town" in ever major city, but we all know where China is not.

b. The references to the "Arabian Sea" and the "Arabian Mountains" does not mean Arabia is inside Egypt, west of the Red Sea or even close by. These references simply mean the Egyptian mountain range flanged entire length the Arabian Sea which separated Egypt from the territory of Arabia proper. The Arabian Troglodytes did however, inhabit the seacoast beside this mountain range and may have been why they were called “Arabian mountains.

2. While Herodotus said that Goshen (Pithom) and the seaport of Arish/Tharu/Rhinocolura was Arabia, he never describes the Sinai Peninsula as Arabia. Strabo calls Arab controlled Rhinocolura a Syrian town.

a. Gordon Franz said, "Herodotus’ description would therefore include all of the Sinai Peninsula in Arabia of his day." (Where is Mount Sinai in Arabia: Galatians 4:25?, Bible and Spade, 2013 AD)

b. Those who use Herodotus to prove the Sinai Peninsula is Arabia in the mind of Herodotus are perpetuating an historical fiction.

3. Herodotus ignored the REAL Gulf of Aqaba, while invented a PHANTOM Gulf of the Nile!

a. Herodotus had no idea the Gulf of Aqaba existed and this explains why he seems to place Arabia so close to the Gulf of Suez.

b. He admits he relied upon second hand reports of the geography of Egypt.

c.

This underscores that his understanding of the Red Sea, Gulf of Suez and

Gulf of Aqaba were flawed.

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.