|

Four Chronology Monographs by Rodger Young and Andrew Steinmann |

|||

|

AD 40 |

1 BC |

2 BC |

6 BC |

|

Caligula’s

Statue & |

Death of Herod the Great |

Consular & Sabbatical Years in Josephus |

Antedating Judean Coins to 6 BC |

Caligula’s Statue for the Jerusalem Temple and

Its Relation to the Chronology of Herod the Great

By Rodger Young and Andrew Steinmann.

JETS 62:4 (Dec. 2019), 759-73.

|

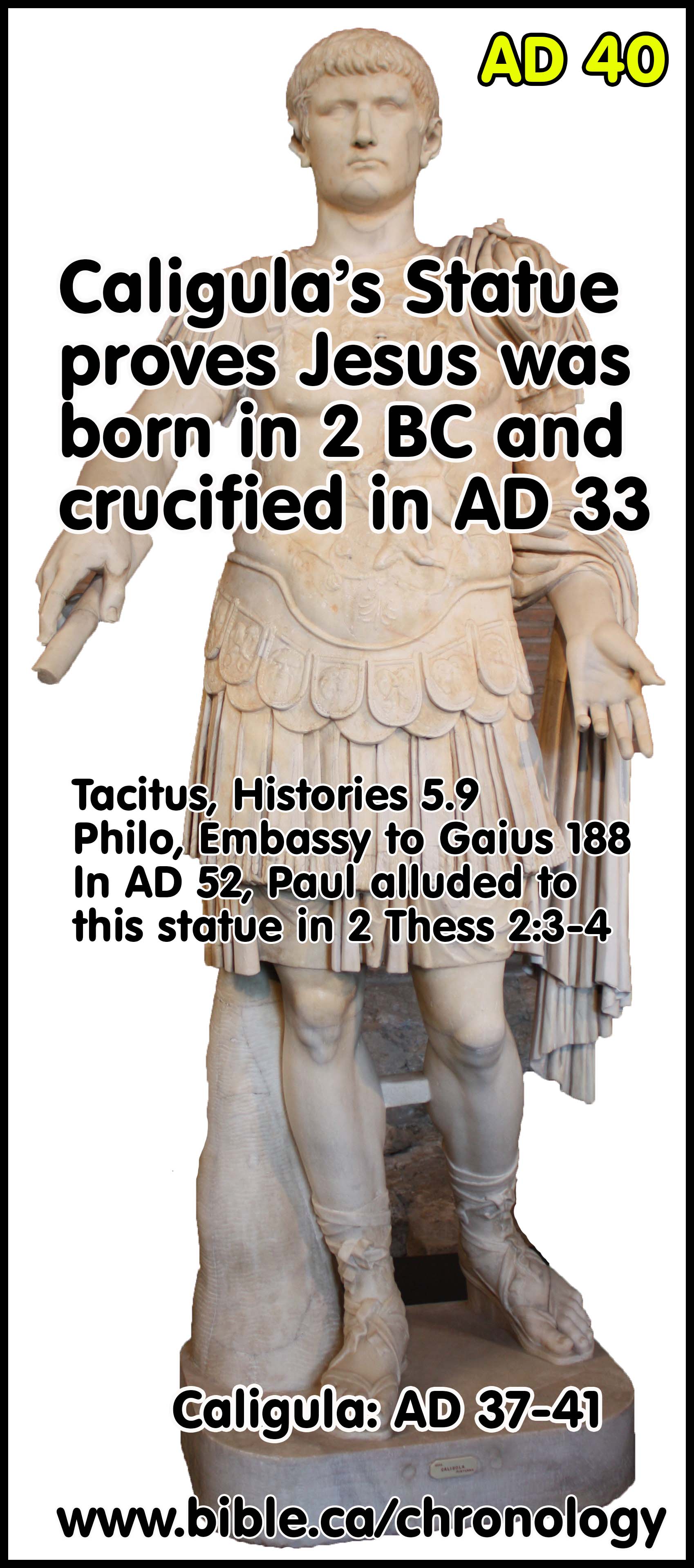

Caligula’s Statue in AD 40 proves Jesus was born in 2 BC

In AD 40, Caligula ordered that a statue of himself, in the guise of the Roman god Jupiter, be placed in the Holy of Holies of the Jerusalem Temple but was murdered before it was set up.

In AD 52 Apostle Paul echoed this past event in 2 Thess 2:3-4.

“Then, when Caligula ordered the Jews to set up his statue in their temple, they chose rather to resort to arms, but the emperor’s death put an end to their uprising.” (Tacitus, Histories 5.9, AD 100)

“Our temple is destroyed! Gaius [Caligula] has ordered a colossal statue of himself to be erected in the holy of holies, having his own name inscribed upon it with the title of Jupiter!” (Philo, Embassy to Gaius, 188, AD 40)

|

Abstract: The Emperor Caligula’s attempt to put a statue of himself, portrayed as the god Jupiter, in the Holy of Holies of the Jerusalem Temple is described by contemporary authors Josephus and Philo of Alexandria. The chronology of this episode is firmly established by these authors as well as by Roman historians. The challenge of that chronology to the consensus chronology for Herod the Great is described, along with the attempts of consensus scholars to deal with the challenge. Closely related to the Caligula statue issue is a Seder ‘Olam passage associating the burning of the Second Temple with a Sabbatical year. New evidence is presented showing that the Seder ‘Olam places that event in the latter part of a Sabbatical year, in conflict with the consensus date for a Sabbatical year during Herod the Great’s siege of Jerusalem but in harmony with the minority view that dates the siege to 36 BC.

Key words: Herod the Great, Emil Schürer, W. E. Filmer, Sabbatical years, Jubilees, NT chronology, Josephus, Seder ‘Olam

In late AD 40, the emperor Caligula announced that a statue of himself, portrayed as the Roman god Jupiter, would be placed in the Temple at Jerusalem. The announcement was the culmination of a series of proclamations and role-playing whereby Caligula presented himself as a divine or semi-divine being. At first the role-playing may have appeared as just cheap theater for the masses, as when their emperor adorned himself with ivy and carried a lyre to imitate Bacchus, the demigod of wine and revelry, or when he dressed in a lion’s skin and carried a club to impersonate the demigod Hercules. But it was not just impersonation. Caligula intended that he really was to be identified as the demigod that was being represented, and further, that he was the embodiment of all the demigods. The charade—or megalomania—went further when he progressed beyond demigods to the gods themselves. He attired himself in the caduceus, sandals, and tunic of Mercury; the garlands, bow and arrows of Apollos; and then the breastplate, sword, and helmet of Mars.[1]

An equally serious chain of events began with the killing in a horrid manner of Caligula’s youthful cousin Gemellus, who had a more legitimate claim to the throne than did Caligula, because Gemellus was the grandson of Tiberius by blood, whereas Caligula was Tiberius’s grandson by adoption. The murdering of a potential rival to power is hardly unusual, as demonstrated in our own day by an aspiring demigod on the Korean peninsula. But Caligula went beyond Kim Jong Un in his treatment of advisors; whereas advisors to the latter only have to be circumspect in what they advise, Caligula determined that no advice at all should be given to a god such as himself. As a god, his opinions and decrees needed no counsel, and to offer such was to show a lack of respect for his affected divine nature. As a consequence of this delusion, he put to death his father-in-law, who mistakenly thought that familial closeness entitled him to offer advice that the son-in-law sorely needed.[2]

The acme of Caligula’s hubris came when he identified himself with Rome’s chief god, Jupiter. Previously, he had been seriously provoked by one populace in the empire that did not humor him in his pretensions to divinity: the Jews. At the instigation of some of his anti-Jewish associates, Caligula devised a plan to break the spirit of the Jews and to establish his cult among them. A colossal statue of himself was to be erected in the Holy of Holies in the Temple at Jerusalem. His name was to be inscribed on the statue, and, accompanying that name, the title of Jupiter, the chief god in the Roman pantheon.

I. Ancient AUthors on Caligula’s statue

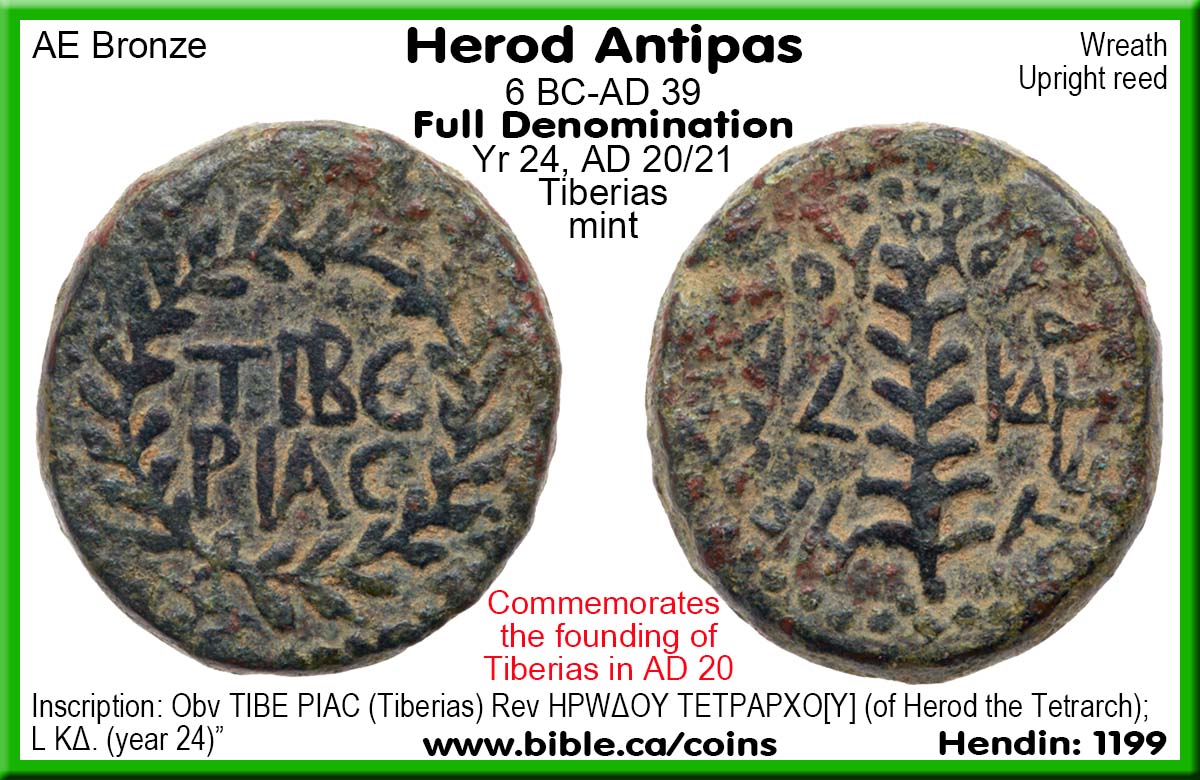

1. Josephus. Josephus describes the consternation that Caligula’s decree caused in Judea.[3] From his lengthy narrative in Antiquities and the shorter version in Wars, we learn that Caligula sent Publius Petronius to be the new governor of Syria and to arrange for the building of the statue. Petronius was also commanded to muster a considerable army for the expected uprising. Petronius sailed to Ptolemais in Phoenicia, where he made preparations to spend the winter of AD 40/41. Since this time corresponds to the agricultural year that began in Tishri (the fall), for convenience in what follows such a year will be written as AD 40t, the ‘t’ showing that the year is reckoned to begin on 1 Tishri instead of on 1 January as in the Roman (and our) calendar.

When the decree was made known in Judea, Josephus relates that “many tens of thousands of Jews” brought their protest to Petronius in Ptolemais.[4] He then made a temporary excursion to Tiberias on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, where “many ten thousands of the Jews met Petronius again.” The protests in Tiberias lasted “for a period of forty days, in the meanwhile neglecting to farm their land during the very season of the year that required them to sow it.”[5] But neglecting their fields when they should have been sowing was not the only way the Jews demonstrated their earnestness; they also told Petronius that they were willing to die rather than see their Temple desecrated.

After hearing their grievous and prolonged supplications, Petronius, a man of more sense than his emperor, told the Jews that he would address a letter to Caligula expressing their concerns. He urged them, “Go, therefore, each to your own occupation, and labor on the land. I myself will send a message to Rome and will not turn aside from doing every service in your behalf both by myself and through my friends.”[6] Surely aware that sending such a letter would jeopardize his life, he nonetheless sent it and told the Jews to “tend to agricultural matters” that they had been neglecting in order to make their desperation known.[7] Meanwhile, in order to buy some time, he told the artisans in Sidon whom he had commissioned to make the statue not to rush its construction, since it was important that it be of the finest workmanship.

News of the statue project therefore reached Judea in the time of sowing, that is, the fall. This is consistent with other early sources we have regarding the Caligula statue and also with the subsequent narrative in Josephus. All sources place the issuing of the statue edict in the late summer or fall of AD 40, with later events playing out in the early months of AD 41. This chronology is important because, as will be shown later, it has unavoidable consequences related to the chronology of Herod the Great in the previous century.

Caligula, on receiving the letter from Petronius, was indeed furious. Although he had previously promised his close friend King Agrippa that the statue would not be placed in the Temple, he reversed this decision and, in a reply to Petronius, essentially demanded that Petronius die—but before taking his life he should make his primary goal the construction and speedy installation of the statue.[8] Caligula’s letter, however, was sent on a slow boat and reached Petronius some time after another letter, written later, came from Rome, telling of the murder of Caligula. He had been killed by members of the Senate and others who had been affected by Caligula’s cruelties and who judged (rightly) that Caligula was insane. The murder of Caligula occurred on January 24, AD 41.

A chief enemy of the Jews in the court of Caligula was the Apion who has achieved infamy throughout the centuries as an anti-Semite because of Josephus’s polemic against him in Contra Apionem. Apion had been an agitator in Alexandria against the city’s large Jewish community. The non-Jewish residents of Alexandria recognized that Caligula’s pretentions to divinity afforded an opportunity to cause great harm to their Jewish neighbors. Their polytheism presented no obstacle to placing statues of the emperor in their places of worship, first in the role of various demigods, and then as portrayed as one of the major gods. Taking advantage of Caligula’s known enmity against the Jewish nation because the Jews were unwilling to ascribe divine honors to him, the Alexandrians correctly determined that there would be no justice for the Jews if they began to plunder their homes and properties. The synagogues were marked out for special attention; what better way to show the disloyalty of the Jews than to place an image of the emperor in a synagogue and then, when this was inevitably resisted by the Jews, to charge them with treason?[9]

As the persecution of the Jews continued for several months, the Alexandrian Jews determined that their only hope for relief was to send a delegation to present their grievances to the emperor, even though they knew of his hostility toward them. To make sure the calumny against the Jews would continue, the pagans sent an embassy at the same time, among whom was Apion.

2. Philo on Caligula’s statue. Caligula reigned from March 13, AD 37 to January 24, AD 41, so Josephus would have been about three years of age when Caligula’s edict about the statue went forth. The story about the decree, and the following events, would therefore have been well known as part of Josephus’s upbringing. The incident would probably have been in Paul’s mind when he received the revelation about the “man of sin” mentioned in 2 Thess 2:3–4, written about eleven years after Caligula’s death.[10] Paul would have seen Caligula, with his pretentions to godhood, as a prefiguration of this end-time figure. The essential facts of Caligula’s mania were thus well known to the contemporary world, while the particulars of the statue incident are borne out by a report from an individual who was intimately involved in the crisis: Philo of Alexandria. Josephus writes that Philo, “a most eminent man . . . and one not unskilled in philosophy,” led the Jewish delegation that protested to Caligula about the ongoing destruction of their homes and synagogues in Alexandria.[11] Philo is best known in modern times for his attempts to syncretize Hebrew monotheism with Greek philosophy. In particular, his concept of the logos as the divine creative principle finds a parallel in the Gospel of John, where the Christ is identified with that principle: “In the beginning was the Logos . . .” (John 1:1).

Philo was born about 20 BC and died about AD 50. He would have been around 60 years of age when he led the embassy to Rome. He described that embassy, and the events related to it, in an extensive work, the Legatio ad Gaium, “The Embassy to Gaius,”[12] that is a mixture of narrative, philosophy, rhetoric, and anti-Caligula polemic. Only part of the original work has survived, but the extant text of over 33,000 words verifies Josephus’s account. This includes the designation of Petronius as the governor who was given the responsibility of commissioning the building of Caligula’s statue and placing it in the Jerusalem Temple. Philo also says that it was in “the middle of the stormy season”[13] (Legatio 190) when he and his party made the voyage to Rome, only to learn after they arrived about the greatest outrage of all, the plan to place the Caligula/Jupiter statue in the Temple. This agrees with the chronology of Josephus, who dated the sending of Petronius to accomplish this task in the late fall of AD 40. It was the time of sowing of seed and just before the army of Petronius went into winter quarters.

II. Was ad 40t a Sabbatical year?

The agricultural year beginning in Tishri (early fall) of AD 40 and ending 12 months later in the early fall of AD 41 could not have been a Sabbatical year. In several passages, Josephus mentions the seriousness of the Jews who, in their protests to Petronius, left off the working of their fields, even though “it was time to sow the seed,” which was done in the fall. After Petronius assured them that he would address a letter to the emperor regarding the statue, he told them to return to their tillage. A similar concern about possible neglect of agricultural work by the Jews appears in the Legatio, where Philo’s delegation, arriving in Rome in the late fall or early winter, learned at that time of the edict regarding the statue. The timeframe for these events is therefore from the fall of AD 40 to sometime in February or March of AD 41, at which time Petronius and the Judean leaders learned of Caligula’s death in the preceding January. The several mentions of agricultural activity by both the Jews and Petronius show that these Jews, who were willing to die rather than see their Temple desecrated, were the same Jews who left off their tillage for 40 days at the critical time of sowing in order to protest to Petronius. They then returned to their labor in the fields when Petronius agreed to send his letter to the emperor. These were not the kind of people who would violate the Mosaic legislation that forbade both sowing and harvesting in a Sabbatical year, especially when we know from various passages in Josephus and 1 Maccabees that the Sabbatical year legislation was being observed in the latter part of the Second Temple period.[14]

If AD 40t was not a shemitah (Sabbatical year), then neither was 38t BC, that is, the agricultural year that began in Tishri of 38 BC and extended through the winter, spring, and summer of 37 BC. The time difference is 77 years, which would make exactly 11 Sabbatical cycles. Yet it is essential to the currently favored chronology for the life of Herod the Great that 38t BC be a Sabbatical year. That chronology places Herod’s siege of Jerusalem in the summer of 37 BC, and advocates of the consensus chronology for Herod, as well as critics of that chronology, accept Josephus’s statements that there was a shortage of food during the summer of the siege because it was the time of a shemitah.[15]

III. How do advocates of the consensus chronology for Herod deal with the non-Sabbatical nature of ad 40t?

The answer is: not very well. There is no reason to doubt the basic facts of the Caligula statue narrative as found in Josephus and Philo, the latter of whom was intimately involved with the unfolding of events: Philo was leading the Alexandrian delegation when they learned of the plans for the statue, and he wrote at great length (some of which is lost) about those events before his death some nine years later. The basic chronology cannot be doubted; the death of Caligula is well established by Roman historians as occurring in January of the year 41. Neither can the repeated references to sowing seed and otherwise preparing the ground for the expected spring harvest be dismissed. The references to agricultural activities by devout Jews is an integral part of the story as related by Josephus. It is therefore of interest to see how defenders of the 37 BC date for Herod’s siege of Jerusalem counter the seemingly insurmountable obstacles that the Caligula/Petronius narrative presents to their chronology.

1. Treatment in Schürer. It is generally recognized that the major source for the chronology of Herod the Great is the work of Emil Schürer in his monumental history of the Jewish people around the time of the Incarnation. There were three German editions of Schürer’s volumes. The first appeared in 1874, the second in 1886–1890, and the third in 1901–1909. Essential to Schürer’s chronology is his acceptance of the consular years given by Josephus for Herod’s investiture as king by the Romans (consuls Calvinus and Pollio, AD 40) and his siege and capture of Jerusalem three years later, with the assistance of a Roman army under Sossius (consuls Marcus Agrippa and Caninius Gallo, AD 37).[16] As W. E. Filmer pointed out, Josephus’s consular year for the siege and fall of Jerusalem is contradicted by Dio Cassius (49:23), who said that during the consular year that Josephus gives for this event, Sossius was not involved in any military activities.[17] There are other indications that Josephus’s two consular years are wrong, yet the majority of subsequent scholars have followed Schürer in building their Herodian chronology on the basis of these consular years.[18]

The Caligula statue episode is one of the many problems in Schürer’s chronology. His equivocation regarding this episode, and his recognition that it was a problem for his reconstruction, are shown in the following passage, as translated from the 1886–1890 German edition:

Against the cycle of the Sabbath year here adopted I argued in the first edition of this work that the year a.d. 40–41 could not have been a Sabbath year, as according to our cycle it must have been. For the Jews omitted to sow the seed in the last month before Caligula’s death, during November a.d. 40, not because it was the Sabbath year, but because for weeks they were going in great crowds to lay before Petronius their complaints on account of the profanation threatened to the temple (Antiq. xviii. 8. 3 ; Wars of the Jews, ii. 10. 5). From this it would appear that the sowing of the fields during that year had been expected. But we are obliged to admit that this indirect argument, when put over against other possible explanations that may still be given, is not strong enough to overturn the very positive proofs that have been advanced in favour of regarding this year as a Sabbath year.[19]

The “very positive proofs” given elsewhere by Schürer are (1) Josephus’s consular years, and (2) Zuckermann’s calendar of post-exilic Sabbatical years. But Zuckermann’s calendar took as its starting place Josephus’s mistaken consular years for Herod. It is obvious from this passage that Schürer had no explanation for the conflict of his chronology with the statue episode, only saying that the chronological evidence from that episode was not consistent with the chronology that he based, ultimately, on Josephus’s two consular dates for Herod.

2. Treatment in Vermes and Millar’s update of Schürer. For a century after Schürer’s first publication, his history of the Jewish people in the time of Christ continued to be considered the authoritative work in the field. During that century it was inevitable that new finds, and new studies based on those finds, made some of Schürer’s scholarship outdated. Geza Vermes and Fergus Millar of Oxford University were therefore given the responsibility of translating Schürer’s third edition into English and updating it with more modern scholarship.[20] Instead of the paltry one paragraph that Schürer devoted to Caligula’s statue in the second edition, the Schürer/Vermes/Millar edition devoted ten pages to events leading up to the statue episode and the episode itself.[21]

Although this is a more satisfactory treatment than the comparative neglect in Schürer’s first two editions, the revision is deficient in dealing with the affair’s chronology. In one place, the authors date the coming of the Jewish embassy to the spring of AD 40,[22] yet on the next page they recognize “Caligula was absent from Rome on an expedition to Gaul and Germany from the autumn of a.d. 39 until 31st August a.d. 40.”[23] Various explanations are offered, all of which are recognized by the authors to have difficulties: that there were two embassies, the first sent in the fall of AD 39 and the second a year later; or that the ambassadors’ journey was at the end of the winter of AD 39/40, after which “they waited in Rome for Caligula’s return from his campaign and were received by him in the autumn of a.d. 40.”[24] These hypothetical scenarios can be evaluated against the testimony of the Legatio. In the Legatio, Philo relates that the embassy traveled to Rome in the “stormy season,” and, in the next sentences after telling of this voyage, they appear in the presence of the emperor, with no indication of any delay or waiting period. It is difficult to understand how this testimony of a respected ancient scholar, one who was a participant in the events being discussed and who wrote about them less than ten years after their occurrence, can so easily be set aside.

Equally strange is that the ten pages devoted to the troubles with Caligula lack any reference to the difficulties that the timing of these events presents to the consensus chronology for Herod the Great. The specific problem is with the Sabbatical year that all agree was in progress when Herod and Sossius were besieging Jerusalem. At least Schürer, in the first and second editions, expressed his discomfort with the evidence from Josephus and Philo demonstrating that his Sabbatical-year calendar was wrong. The failure of the issue to even be mentioned in the Vermes/Millar edition shows that no solution had been found.

3. Treatment in Goldstein and subsequent writers. In his 1976 commentary on 1 Maccabees, Jonathan Goldstein recognized that neither Schürer nor Vermes and Millar had dealt adequately with the challenge of the statue incident to the consensus Herodian chronology. Referring to Ben Zion Wacholder’s alternative[25] to Zuckermann’s (and consequently Schürer’s) Sabbatical year calendar, Goldstein writes:

Wacholder (p. 168) asserts that the year from Tishri, 40 c.e., to Tishri, 41 c.e., could not have been a sabbatical year because Josephus in his account of the momentous events of the reign of the Roman emperor Caligula attests that pious Jews of Judaea sowed their fields in that year (BJ ii 10.5.200; AJ xviii 7.3–4.271—74). But Philo (Legatio ad Gaium 33–34.249–57) puts the same events, not at the time of the autumn sowing, but at the time of the spring harvest.[26] Hard as it may be to explain how Josephus could have been mistaken, it is harder still to explain how Philo could have been in error; see F. H. Colson, Philo X, LCL, no. 379 (1962), pp. xxvii–xxxi. The problem is still unsolved (the suggestions of Vermes and Millar in Schürer, History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ [New English Version] are unsatisfactory too; Philo and Josephus cannot both be correct). But one certainly cannot take Josephus’ chronology of the events of Caligula’s reign as a sure basis for a theory of the dates of the sabbatical year.[27]

Very strange. We don’t need to take Josephus as the authority for the chronology of Caligula’s reign as Goldstein intimated; it is well established by Roman writers. Goldstein recognizes that Vermes and Millar did not solve the problem that the statue episode presents to the consensus chronology for Herod: “The problem is still unsolved.” The whole point of the episode is lost if it did not take place in a few months before and then shortly after January 24, AD 41, when Caligula was murdered. So to Schürer, Vermes, and Millar we must add Goldstein among those who have not been able to reconcile their chronology for Herod with the course of events for Caligula’s statue. There is no problem, however, with Wacholder’s Sabbatical-year calendar that is one year later than Zuckermann’s, so that Herod’s siege of Jerusalem was in the summer of 36 BC and a Sabbatical year began nine months after the death of Caligula in AD 41.

To the best of our knowledge, subsequent writers who support the Schürer consensus have done no better. In an article intending to support the Zuckerman Sabbatical-year calendar, Don Blosser gave considerable attention to various incidents that he maintained supported Zuckermann’s calendar, such as Herod’s siege of Jerusalem as reported in Josephus and the fall of Jerusalem to Titus in what he reckoned to be a post-Sabbatical year.[28] Regarding Caligula’s statue, however, Blosser only refers to it in his list of Sabbatical years at the end of his article, saying that AD 40/41 was the year of the Statue of Caligula, and that this was 77 years (11 Sabbatical cycles) after the conquest of Jerusalem by Herod and 28 years (four Sabbatical cycles) to the year before its conquest by Titus.[29] There is no explanation of the evidence that the “year of the statue” could not have been a Sabbatical year.

Despite Goldstein’s comment that the problem the Caligula statue presents to the Schürer chronology is still unsolved, there is a simple solution: consider that Josephus’s consular years for Herod’s investiture by the Romans and, three years later, the siege of Jerusalem, might be in error. Then develop a chronology that does not depend on Josephus’s consular years and see if it agrees with other chronological markers in Josephus and elsewhere related to Herod. There is, after all, another historian, Dio Cassius, who wrote extensively about events related to Rome and Judea in this time. As Filmer pointed out,[30] Dio said that in the consular year corresponding to 37 BC,

the Romans accomplished nothing worthy of note in Syria. For Antony spent the entire year in reaching Italy and returning again to the province; and Sosius, because anything he did would be advancing Antony’s interests rather than his own . . . spent the time in devising means, not for achieving some success and incurring his enmity, but for pleasing him without engaging in any activity. (Dio 49:23)

Schürer apparently thought that the testimony of Dio regarding the non-activity of Sossius in 37 BC could be discarded because Dio put the conquest of Jerusalem a year earlier, an untenable position.[31] That, however, represents a misreading of Dio. In the relevant passage referring to events in the consulship of Claudius and Norbanus (38 BC),[32] Dio deals with Mark Antony’s siege of Antiochus at Samosata, which all agree took place in 38. In the course of the same paragraph, Dio introduces Sossius as the governor that Antony appointed for Syria and Cilicia. Further describing Sossius, he mentions that he was the one who subdued the Aradii “and also conquered in battle Antigonus . . . and reduced him by siege when he took refuge in Jerusalem.” The paragraph ends with a statement that Antony entrusted the government of the Jews to “a certain Herod,” an event that happened three years before the siege of Jerusalem. Dio, therefore, was not placing all these events in the same year, as Schürer implied. After this aside explaining who Sossius was, Dio returns to his main narrative about Antony and his struggle against the Parthians. The testimony of Dio that contradicts Josephus’s consular years therefore should not be discredited by any interpretation that has him dating the capture of Jerusalem to 38 BC, and appropriate weight should be given to his statement that, in the consular year corresponding to 37 BC, “the Romans accomplished nothing of note in Syria.”

IV. The Sabbatical year for the fall of Jerusalem

Virtually all historians who deal with the calendar of post-exilic Sabbatical years place great weight on the testimony of the Seder ‘Olam regarding a Sabbatical year associated with the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans. The principal author of the Seder ‘Olam, Rabbi Yose ben Halaphta, was a disciple of the renowned Rabbi Akiba. Akiba (ca. AD 50 – AD 135 or later) was a young man when this calamity happened. Akiba’s knowledge of when it occurred would have been of great interest to Rabbi Yose, whose primary concern in the Seder ‘Olam (hereinafter SO) is chronology. His chronological scheme is accepted as authoritative in the Tosefta and both Talmuds,[33] all of which quote verbatim (in Hebrew) the SO 30 passage cited below.[34] There is no discussion of alternative views, showing that the quotation from SO 30 was considered authoritative on this subject, backed, as it was, by eminent and credible witnesses and authorities. The passage in SO 30 regarding the Sabbatical year associated with the fall of Jerusalem appears as follows in Guggenheimer’s translation:

R. Yose says: A day of rewards attracts rewards and a day of guilt attracts guilt. You find it said that the destruction of the first Temple was at the end of Sabbath, at the end of a Sabbatical year, when the priests of the family of Yehoiariv was [sic] officiating, on the Ninth of Ab, and the same happened the second time. Which song did they sing? (Ps. 94:23) “He repaid them for their evil deeds . . . .”

For those unfamiliar with the controversy regarding this passage, the above quotation would seem to end the argument: the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans was in the latter part of (“at the end of”) a Sabbatical year. The Sabbatical year would have begun in Tishri of AD 69, with the destruction of the Temple occurring ten months later, in Ab (July/August), AD 70. This is consistent with Wacholder’s Sabbatical-year calendar, not Zuckermann’s, so that the Sabbatical year associated with the siege of Jerusalem was 37t BC, not Schürer and Zuckermann’s 38t. The consequence is that Josephus’s consular years for the event must therefore be rejected, and the consular year statement of Dio be accepted as accurate: Herod and Sossius’s siege of Jerusalem took place in the summer of 36 BC, not a year earlier as in the Schürer chronology.

The controversy, however, centers on the translation, or interpretation, of this passage from the Seder ‘Olam. Many translations of the SO, Tosefta, and Talmudic presentations interpret the crucial phrase about the Sabbatical year so as to say that it was “the year after” a shemitah, rather than the latter part of (Guggenheimer: “at the end of”) a shemitah. Other translations of the same passage into English agree with Guggenheimer’s rendering. In what follows, it will be shown from what Rabbi Yose says elsewhere in the SO that Guggenheimer’s translation is correct, and therefore the SO, the Tosefta, and both Talmuds testify against the Zuckermann/Schürer Sabbatical-year calendar, supporting instead Wacholder’s calendar.

In this discussion, the various other “coincidences” cited by Rabbi Yose for the two Temple burnings are usually ignored: that it was the same day of the week, that the same priestly family was officiating, and that the same hymn was being sung. These seem like fanciful extrapolations of the three coincidences that both Temple burnings occurred on the same day of the same month and in the same year of a Sabbatical cycle.[35] Therefore the focus here will be on the phrase that Rabbi Yose uses to associate both Temple burnings with a Sabbatical year: it was מוֹצָאֵי שְׁבִעִית, motsae shevith. Motsae is the plural participial form of the common verb yatsa, to go out or to go forth. There is nothing in this verb or any of its declensions that suggests the idea of “after,” as would be required by those who interpret the phrase to mean “after a seventh year (Sabbatical year).”[36]

An equally strong, or even stronger, argument in favor of Guggenheimer’s (and others’) translation that renders this phrase to designate the latter part of a Sabbatical year is found from what Rabbi Yose wrote elsewhere in the Seder ‘Olam.[37] It goes as follows: In SO 25, Rabbi Yose says that Jehoiachin’s exile began “in the middle of a Jubilee cycle, in the fourth year of a Sabbatical cycle.” Jehoiachin was taken captive on the second of Adar, 597 BC, which was in the Jewish regnal year (and agricultural year) beginning in Tishri of 598 BC (598t).[38] The city was captured in the summer of 587 BC, eleven Tishri-based years later.[39] If 598t was the fourth year of a Sabbatical cycle (SO 25), then 595t would have been a Sabbatical year, as would 588t. The latter is the year in which Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians. Whatever his other faults in calculating elapsed years, Rabbi Yose was very conscious of how the Jubilee and Sabbatical years interacted with his chronological scheme, and so this shows what Rabbi Yose meant when he said that both Temples were burnt in the מוֹצָאֵי שְׁבִעִית of a Sabbatical year: it was the latter part of that year.

The argument that this is the correct interpretation of SO 30 can be reinforced by other passages in the Seder ‘Olam in conjunction with the finds of modern scholarship for the chronology of the Hebrew kingdom period. Rabbinical scholarship, including that of Rabbi Yose, could not have anticipated these results because it always reckoned the lengths of reigns of the kings of Judah in an inclusive (non-accession) sense. Rabbi Yose makes this inclusive reckoning explicit in SO chapters 4 and 12. Turning to Rabbi Yose’s interest in the Jubilee cycles, he relates in SO 24 that a Jubilee was observed in the 18th year of King Josiah, and in SO 11 that Ezekiel saw the vision that occupies the last nine chapters of his book at the beginning of a Jubilee year.[40] These dates must have been based on historical remembrance rather than later rabbinic calculation, because the inclusive method of the rabbis would only give 47 years between the two jubilees, rather than the correct 49 years (623t to 574t BC) given by modern scholarship and calculated independently of any reference to the Jubilee cycles.[41] Israel’s priests, one of whom was Ezekiel, must have been keeping track of the Jubilee and Sabbatical cycles, as it was their duty to do even when the people ignored the stipulations in the Torah regarding these years, so that, when Ezekiel saw his vision on the Day of Atonement, 574 BC, he knew that it was the beginning of a Jubilee year.

It was demonstrated above that when SO 30 declared that Jehoiachin was taken captive in the fourth year of a Sabbatical cycle, this showed that the passage must be interpreted so that the Tishri-based year in which Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians was a Sabbatical year. To this must be added the evidence of the Jubilee cycles, as given in the Seder ‘Olam. Ezekiel says that he saw his vision 14 years after the city fell (Ezek 40:1). Since this was a Jubilee year, then 14 years earlier would have been a Sabbatical year. The same argument applies to the previous Jubilee, in the 18th year of Josiah: from 623t to 588t is 35 years, or five Sabbatical cycles.

It is always possible to dismiss all statements related to Jubilee and Sabbatical years in the Seder ‘Olam, and their later citations in the Tosefta and the Talmuds, as unhistorical; unbridled skepticism about ancient authors is regarded as evidence of “impartiality” in some circles. But at the very minimum, the present excursus shows that it is improper to translate SO 30 to say that the Temples were burnt in a post-Sabbatical year. Rabbi Yose was definitely saying that both burnings were in Sabbatical years. With this realization, those who support the Schürer consensus for the year in which Herod and Sossius captured Jerusalem can no longer appeal to SO 30 to support their position. The SO passage, and its repetition in the Tosefta and Talmuds, unequivocally support a Sabbatical-year calendar that places the siege in the summer of 36 BC.

This evidence from rabbinic literature showing that AD 69t was a Sabbatical year necessarily implies that the consular dates given by Josephus for Herod’s investiture by the Romans and the siege of Jerusalem must be rejected, and along with them, Zuckermann’s calendar of post-exilic Sabbatical years that was built on Josephus’s consular dates. Other Sabbatical years then fall into harmony: the Sabbatical years associated with Judas Maccabeus’s siege of Beth-Zur and, 28 years later, John Hyrcanus’s siege of Ptolemy in the Hasmonean period,[42] and the non-Sabbatical nature of AD 40t, the year of the Caligula statue episode. This is quite a sequence of events that are in agreement once the simple expedient is taken of considering that Josephus’s consular years for Herod might be mistaken, and credibility should be given instead to the consular years of Dio Cassius.

V. Conclusion

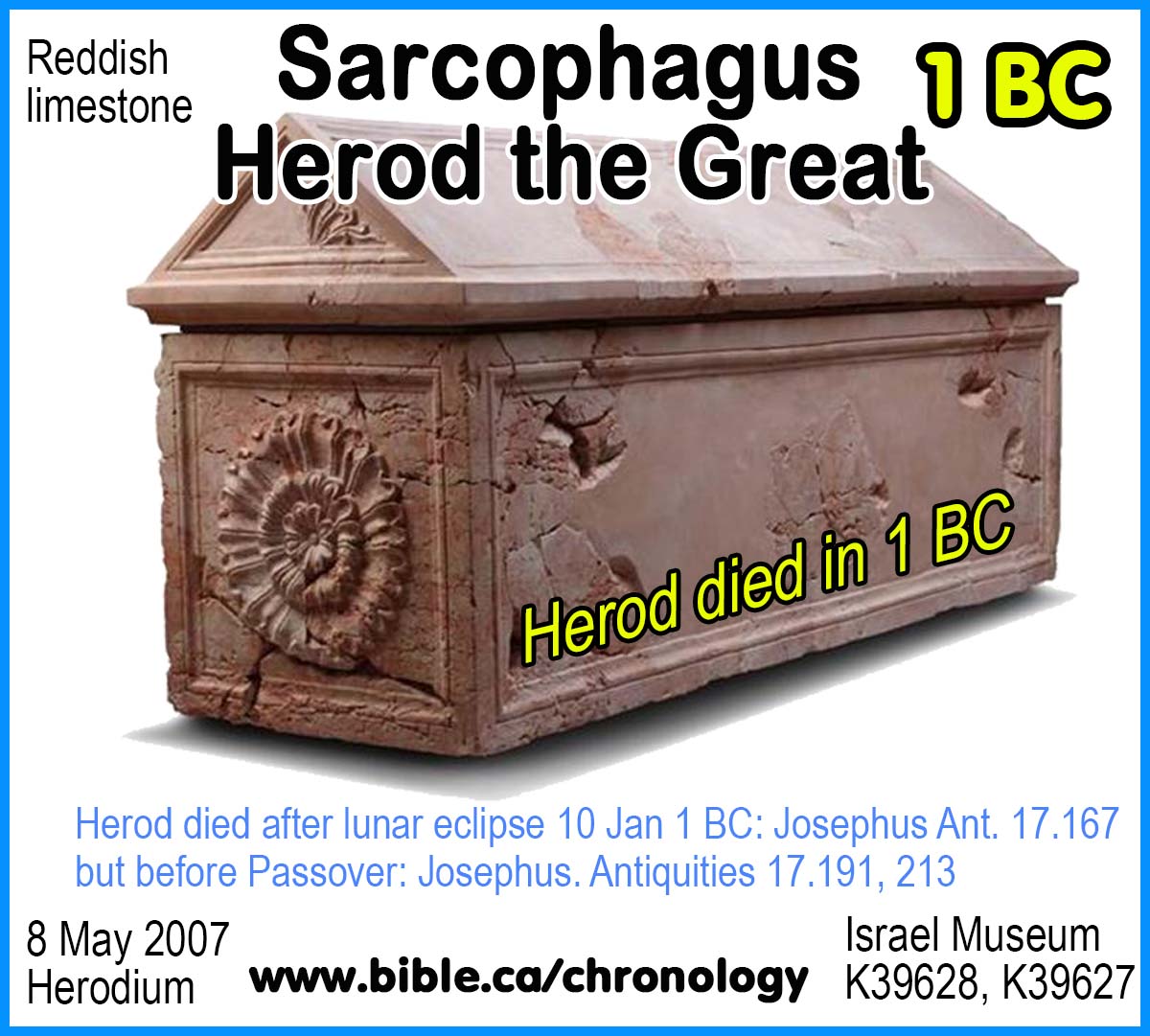

It is unlikely that advocates of the consensus chronology for Herod will make the simple adjustment of moving Herod’s (and Sossius’s) siege of Jerusalem one year later based on the evidence of the Sabbatical years, as reasonable as it might seem based on what has been presented above about the inadequacy of the Zuckermann calendar. To do so would move Herod’s death to 3 BC according to the Nisan-based calendar and inclusive reckoning of the consensus approach, or to 2t BC if Tishri-based years are used along with the non-inclusive reckoning that Josephus uses consistently for other elapsed times in the reign of Herod.[43] Either of these alternatives would mean that Herod’s death was after 4 BC, the year to which Herod’s three sons dated the start of their reign, thus supporting the thesis of Filmer (and others) that the three sons back-dated their reigns to a time before the death of their father and their assuming fully independent responsibility as tetrarchs. Any of these adjustments would mean that the consensus view is no longer tenable.

A discussion of antedating for Herod’s sons is beyond the scope of the present paper. Neither is it possible to cover all aspects of the long-continuing Zuckermann-Wacholder controversy regarding the calendar of Sabbatical years in the post-exilic period. It is hoped, however, that advocates of the Zuckermann/Schürer Sabbatical-year calendar will consider seriously the challenge that Seder ‘Olam chapter 30, which is often cited in support of their position, presents to their chronology when it is understood as Rabbi Yose meant it to be understood. It is also hoped that all who are concerned about having the correct chronology for the birth and subsequent ministry of our Lord will recognize the challenge that Caligula and his statue present to the consensus chronology for Herod the Great, and will look anew at the chronological implications from ancient and credible authors—Josephus and Philo—who described this remarkable episode in the life of the Jewish nation.

|

Four Chronology Monographs by Rodger Young and Andrew Steinmann |

|||

|

AD 40 |

1 BC |

2 BC |

6 BC |

|

Caligula’s

Statue & |

Death of Herod the Great |

Consular & Sabbatical Years in Josephus |

Antedating Judean Coins to 6 BC |

What you read in the book you find in the ground!

Uploaded by Steven Rudd with written permission: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

[1] The progressive delusions of Gaius/Caligula are described in rather wordy detail in Philo, Legat. 78, 79, 93–97, available online at http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book40.html. The decree of Caligula to set up his statue in the Jerusalem Temple is also mentioned in Josephus (see below) and Tacitus, Hist. 5:9.

[2] Legatio 64, 65.

[3] Ant. 18.261–309/18.8.2–18.8.9; J.W. 2.184–203/2.10.1–5.

[4] Ant. 18.263/18.8.2. Translation from Louis H. Feldman, Josephus with an English Translation, vol. 9 (LCL; Cambridge: Harvard University, 1965), 157.

[5] Ant. 18.272/18.8.3. J.W. 2.200/2.10.5 also says that it was seed time, but puts the number of days of protest at 50.

[6] Ant. 18.283/18.8.5.

[7] Ant. 18.284/18.8.6.

[8] Ant. 18.304/18.8.8; Philo, Legatio, 258.

[9] Legat. 132, says of the synagogues in Alexandria, “there are a great many in every section of the city.” In Legat. 138, Philo says that for three hundred years prior to these desecrations, no king had any images or statues of themselves erected in a synagogue, thereby indicating that the institution of the synagogue began about 260 BC.

[10] Andrew E. Steinmann, From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical Chronology (St. Louis: Concordia, 2011), 334.

[11] Ant. 18.259/18.8.1.

[12] “Caligula,” meaning “Little Boots,” is a nickname that was given to the future emperor by Roman soldiers when he was a boy. His full name was Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, usually abbreviated to Gaius Caesar.

[13] χειμῶνος, BAGD, s.v. χειμών,ῶνος,ὁ [χεῖμα ‘winter weather, storm’] ‘inclement weather condition’ bad weather, . . adv. gen. χειμῶνος in winter Mt 24:20; Mk 13:18.

[14] 1 Macc 6:49; Ant. 14.202/14.10.5, 14.206/14.10.6, 14.475/14.16.2, 15.7/15.1.2. Unlike the First Temple period, when the people generally did not observe the stipulations of the Sabbatical years, Josephus says that in his days and in the days of Herod the Great, “we are forbidden to sow the earth in that year” (Ant. 15.7/15.1.2).

[15] Ant. 14.475/14.16.2, 15.7/15.1.2.

[16] Ant. 14.389/14.14.5; Ant. 14.487/14.16.4.

[17] W. E. Filmer, “The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great,” JTS n.s. 17 (1966): 287.

[18] Josephus’s consular dates also formed the starting point for the calendar of post-exilic Sabbatical years originated by Benedict Zuckermann several years before Schürer published his magnum opus. (Benedict Zuckermann, A Treatise of the Sabbatical Cycle and the Jubilee: A Contribution to the Archaeology and Chronology of the Time Anterior and Subsequent to the Captivity Accompanied by a Table of Sabbatical Years. [trans. A. Löwy; London: Chronological Institute, 1866]; orig. German ed, 1857). After a lengthy discussion of the background of Jubilee and Sabbatical years, Zuckermann looked for an anchor point to which he could assign one Sabbatical year in the post-exilic period. If that could be done, then prior and subsequent Sabbatical years could be calculated over a long span of time. He thought that he found this in Josephus’s consular year for the siege of Jerusalem by Herod and Sossius, calling this the “best ascertained fact” that he needed to construct such a calendar (p. 45). In the next two pages, however, Zuckermann ran into difficulties with two Sabbatical years in the Hasmonean period, as derived from Josephus and 1 Maccabees. His mistranslation of the relevant texts in Josephus, and his general failure to resolve the difficulty that resulted from his acceptance of wrong consular years from Josephus, will be dealt with elsewhere. For the present it should be noted that Zuckermann’s Sabbatical-year calendar was accepted by Schürer as an independent verification of his Herodian chronology, whereas it is not independent because both rely on Josephus’s consular year mistakes for Herod. When a proper consideration is given to the possibility that Josephus erred in the matter of consular years (and that Dio Cassius was correct), a series of other problems related to the consensus chronology for Herod is resolved. See Andrew E. Steinmann, “When Did Herod the Great Reign?” NovT 51 (2009): 1–29 and Andrew E. Stenimann and Rodger C. Young, “Elapsed Times for Herod the Great in Josephus,”BSac (2020): forthcoming.

[19] Emil Schürer, A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ, 5 vols., trans. John Macpherson (repr. Peabody,MA: Hendrickson, 2009), 42, 43. Original publication: Edinburgh T. & T. Clark, 1890.

[20] Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.–A.D. 135): A New English Version Revised and Edited by Geza Vermes & Fergus Millar (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1973).

[21] Ibid., ii. 389–98.

[22] Ibid., ii. 392.

[23] Ibid., ii. 393, n. 167.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ben Zion Wacholder, “The Calendar of Sabbatical Cycles during the Second Temple and the Early Rabbinic Period,” HUCA 44 (1973): 153–96.

[26] Goldstein’s understanding that Philo put these events in the spring is based on an admittedly confusing passage, Legatio 33–34 (249–60), that deals with Caligula’s writing a letter to Petronius, who was in Phoenicia or Judea. This was in response to the letter that Petronius had sent earlier, expressing concern about the Jews not tilling the ground because of the statue issue. The Legatio passage in its present form could be read as if it was already time to harvest the spring wheat crop. Caligula, however, was dead many weeks before the harvest of AD 41, and so the letter could not have been written in the spring of that year. Neither could it have been written in the spring of AD 40, because Caligula was in Gaul in the first part of AD 40, not returning to Rome until August of that year (OCD “Gaius”). The remarks about spring in section 33 and 34 of the Legatio should be interpreted in light of Caligula’s concern that, if the coming harvest should fail because of the lack of sowing and tillage, there would be inadequate food for the Roman legions in Syria in the spring. This was also the time that the statue was to be placed in the Jerusalem Temple. Although it is easy to understand how the passage could be misunderstood, Josephus and Philo are not in error about the timing of these events. They agree in dating them to the fall and early winter of AD 40/41, well before the spring harvest.

[27] Jonathan Goldstein, I Maccabees: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (AB 41; Garden City NY: Doubleday, 1976), 316–17.

[28] Don Blosser, “The Sabbath Year Cycle in Josephus,” HUCA 52 (1981), 129–39.

[29] See the discussion below; Jerusalem fell to Titus in a Sabbatical year, not a post-Sabbatical year.

[30] Filmer, “Chronology of Herod the Great,” 287.

[31] Schürer, History (Macpherson translation), 396 n. 11.

[32] 49:22.

[33] H. Guggenheimer, Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology (Northvale, NJ/ Jerusalem: Jason Aronson, 1998), ix.

[34] t. Ta‘an. 3:9; y. Ta‘an. 4:5; b. ‘Arak. 11b, 12a; b. Ta‘an. 29a.

[35] Josephus, an eye-witness of the burning of the Second Temple, says it took place on the tenth of Ab: “and now, in the turning of the ages, that fatal day had come, on the tenth of the month Lous [Ab], the very day it was burned long ago by the king of Babylon” (J.W. 6.250/6.4.5). The explanation in the Talmud of why Rabbi Yose dated both burnings to the ninth of Ab (b. Ta‘an. 29a) is not satisfactory. Putting the burning on the ninth of the month is contrary to Josephus for the Second Temple and Jer 52:12 for the First Temple. The reason for the slight adjustment in the SO is apparently because the Bar-Koseba rebellion came to an end on the ninth of Ab, AD 135, and Rabbi Yose’s mentor, Rabbi Akiba, saw the messianic hopes he pinned on Bar-Koseba dashed when Bar-Koseba was killed and his fortress taken on that date. By a slight adjustment of one day, the ninth of Ab could be associated with other calamities that came upon the Jewish nation, including the two Temple burnings. See the discussion of the days for the two Temple burnings in Rodger C. Young, “The Parian Marble and Other Surprises from Chronologist V. Coucke,” AUSS 48:2 (2010), 243–4 n. 46, and Steinmann, From Abraham to Paul, 166–7.

[36] Jastrow gives a

one-word definition of מוֺצָא: “exit.” This agrees with a

rather literal definition from the etymology, “going-out.” He cites one passage

from the Tosefta and five passages from the Talmud, but in two of these

passages he renders a slightly different meaning so as to give “the night

following the Sabbath,” and “the night following a Holy Day.” Nevertheless,

examination of a few passages Jastrow cites leads to a different

conclusion—that מוצא is a reference to the ending of a period of time, not to a

subsequent period. These passages are:

1. b. Ḥul.

15a: רבי

יוחנן הסנדלר

אומר בשוגג

יאכל למוצאי שבת

לאחים ולא לו... Rabbi Yoḥanan Hasandlar says: [If he cooked

food on the Sabbath] unwittingly, it may be eaten up to the conclusion of the

Sabbath by his fellows, but not by him… This discussion is about food cooked on the

Sabbath. Yoḥanan appears to be saying that if someone cooked food

unwittingly on the Sabbath [whatever that might mean—perhaps being unaware that

it was a Sabbath day?] that the food could be eaten by others without

violating the Sabbath regulation, but could not be eaten by the cook.

2. b. Beṣ 30b; b. Šabb. 45a: ...אסור

להסתפק מהן עד

מוצאי יום

טוב האחרון... …it is prohibited to gain benefit

[from eating sukka ornaments] until the conclusion of the last festival day.

This is a treatment concerning the nuts and fruits that were used to decorate a

booth during the Feast of Tabernacles. It appears to allow eating of these

during the conclusion of the final day of the festival when the booth would be

dismantled.

3. b. Roš Haš. 9a: ...וקציר

של שביעית

היוצא למוצאי

שביעית …and the harvest of the Sabbatical Year which is

concluding up to the conclusion of the Sabbatical Year. This is a discussion of

sowing and harvesting during the Sabbatical Year. In Roš Haš. 9a the

rabbis are prohibiting cheating that might occur by sowing a field immediately

before the Sabbatical Year’s beginning in Tishri (discussed earlier in 9a) and

then reaping the harvest during the Sabbatical Year. Since the law in Lev 25:5

prohibits only reaping crops that grew up by themselves (ספיח) during the Sabbatical Year, one might

argue that it was permitted to harvest these crops, since they were sown and,

therefore, were not crops that were ספיח. Thus, in the second part of the

Sabbatical year that is “going out” (היוצא, i.e., from Nisan to Tishri), harvesting

such sown fields is also prohibited up to the conclusion of the Sabbatical

Year.

Moreover, in regard to the SO passage, it is implausible to make the “goings-out” of a Sabbatical year to refer, not to sometime around the end (“exit”) of that year, but to the time of Temple burnings near the end (the tenth month) of the next year, which is the consensus understanding of the passage in SO 30. While these arguments against the consensus (mis)translation of SO 30 are substantial, the definitive evidence that defeats the consensus interpretation is Rabbi Yose’s clear and consistent chronology of Sabbatical and Jubilee years, as discussed in the main text.

[37] The argument about Jehoiachin’s exile beginning in the fourth year of a Sabbatical cycle was first published in Rodger C. Young, “Seder Olam and the Sabbaticals Associated with the Two Destructions of Jerusalem: Part 1,” JBQ 34 (2006): 178. The further agreement of the Jubilee years with the Sabbatical year in which Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians is not mentioned in the JBQ article.

[38] D. J. Wiseman, Chronicle of Chaldean Kings (London: British Museum, 1956), 33.

[39] For the demonstration from both biblical and Babylonian records that Jerusalem fell in 587 BC, not 586, see Rodger C. Young, “When Did Jerusalem Fall?,” JETS 47 (2004): 21–38.

[40] That Ezekiel’s vision was at the beginning of a Jubilee year is also indicated by the Hebrew text of Ezek 40:1. Ezekiel said that he saw his vision on Rosh HaShanah (New Year’s Day), and it was also on the tenth of the month. Rosh HaShanah was on the tenth of the month (the Day of Atonement) only at the start of a Jubilee year (Lev 25:9, 10). Since Israel’s priests knew when the Jubilee year was due, it would also be logical to assume that they kept track of which Jubilee it was, making it reasonable that the Seder ‘Olam preserved correctly that it was the 17th Jubilee. That would date the entry into the land, at which time Israel was commanded to start counting for the Jubilee/Sabbatical cycles (Lev 25:2-4), to 1406 BC. The same year is derived from 1 Kgs 6:1 independently of the Jubilee cycles. The “coincidence” shows that Israel’s priests started their counting at that time, with the consequence that the Mosaic legislation was in effect in 1406 BC.

[41] That the Jubilee cycle was 49 years, not 50 years as might be suggested by a cursory reading of Lev 25:8–11, is generally accepted in current scholarship. Some writers, however, maintain that the Jubilee followed the seventh Sabbatical year and was also the first year of the next seven-year cycle. This would preserve the cycle length of 49 years but would have the land fallow for two consecutive years. See the refutation of this interpretation, showing that two fallow years in succession were never intended in the legislation, in Jean-François Lefebvre, Le Jubilé Biblique: Lv 25 — Exégèse et Théologie (OBO 194; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003), 159–61.

[42] 1 Macc 6:20, 49, 53; Ant. 13.235/13.8.1; J.W. 1.60/1.2.4.

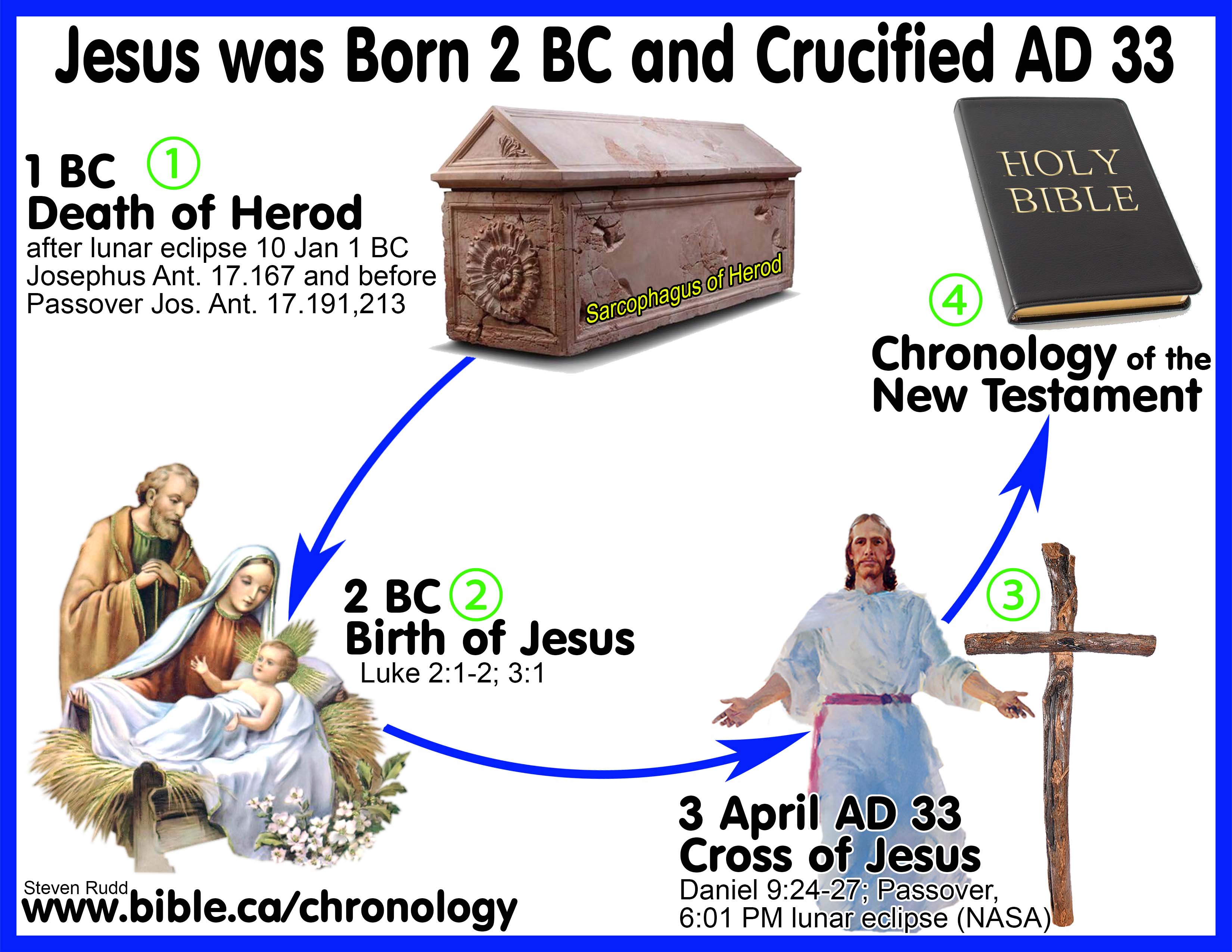

[43] For the demonstration that Josephus consistently used non-inclusive (accession) reckoning for the elapsed times in Herod’s chronology, see Steinmann and Young, “Elapsed Times for Herod the Great” forthcoming. That Herod’s final year was 2t BC is consistent with Filmer’s date for his death at some time between the total lunar eclipse of January 9/10 1 BC and the start of Passover on April 8 of that year.