Herod the Great’s Sons Antedated Their Reigns to 6 BC

Jesus was born in 2 BC not 6 BC

Andrew E. Steinmann, River

Forest, Illinois

Rodger C. Young, St. Louis, Missouri

|

Antedating the coins of Archelaus, Antipas, and Philip to 6 BC New and groundbreaking research examines the numismatic evidence from the coins of Archelaus, Antipas, and Philip as clear evidence they backdated their coins to 6 BC after Herod the Great died in 1 BC. |

|

Four Chronology Monographs by Rodger Young and Andrew Steinmann |

|||

|

AD 40 |

1 BC |

2 BC |

6 BC |

|

Caligula’s

Statue & |

Death of Herod the Great |

Consular & Sabbatical Years in Josephus |

Antedating Judean Coins to 6 BC |

Evidences That Herod the Great’s Sons Antedated Their Reigns to a Time before Herod’s Death

Andrew E. Steinmann

River Forest, Illinois

Rodger C. Young

St. Louis, Missouri

Abstract:

In previous papers we have argued that the consensus view of the date for Herod’s death (i.e., early 4 bc) is contradicted by a variety of evidence and that Herod died in early 1 bc. In this paper we examine the only remaining pillar upon which the consensus rests, the dating of the reigns of his sons who succeeded him. We note that ancient historians, notably Josephus, contain indications that Herod’s sons received royal prerogatives before Herod’s death. It is proposed that this happened sometime in the year that began in Tishri 6 bc, and it was to this date that Herod’s sons back-dated their reigns which actually began sometime in 1 bc. We also examine the numismatic evidence of the coins issued by Herod and his sons and demonstrate that it confirms this view, thereby removing the final pillar that supports the consensus chronology for Herod’s reign.

INTRODUCTION:

PROBLEMS WITH THE CONSENSUS CHRONOLOGY FOR HEROD THE GREAT

The strongest argument for the consensus dating of Herod the Great’s death is that his three sons dated the beginning of their respective jurisdictions to 4 bc or shortly before. By taking inclusive numbering for Herod’s 37-year and 34-year reign lengths, as well as for the years of reign of Herod’s successors, the two sets of numbers seem to converge so as to place Herod’s death in the restricted timeframe of Nisan 1 to Nisan 14 of 4 bc. The Nisan 1 starting date for this period follows from the consensus chronology that places Herod’s investiture by the Romans in late 40 bc and his capture of Jerusalem in the Nisan-based year that began on Nisan 1 of 37 bc. The Nisan 14 terminus ad quem for his death is because Josephus (Ant. 14.165/14.9.3) depicts Herod’s son Archelaus on the throne before the beginning of Passover not long after Herod died.

The problems with this chronology are numerous. Because they have been treated extensively in the preceding two papers in this series[1] they will only be summarized briefly here:

(1) Even if Herod died at the earliest possible point in the period from Nisan 1 to Nisan 14 of 4 bc, that does not allow enough time for the word to get from Jericho to Jerusalem to gather the articles for the funeral, the actual gathering of those articles, their subsequent freighting to Jericho, the solemn funeral march from Jericho to the Herodium, followed by the internment and seven days of mourning, all followed by the initial favorable reception of Archelaus by the people and their subsequent rejection of his policies before the Passover began on the fourteenth of the month.

(2) The Nisan-based calendar that is essential to the consensus system is refuted by Josephus when he says that in matters of government (διοίκησις: “government, administration”), his people followed a Tishri-based calendar (Ant. 1.81/1.3.3).[2]

(3) Herod’s appointment as king is explicitly dated by Appian (V:75) as occurring after the Treaty of Misenum (August 39 bc).

(4) Plutarch (Antony 33) and Dio Cassius (48:36-39) state that the Senate’s appointment of Ventidius to drive the Parthians out of Phoenicia and Syria was also after the Treaty of Misenum. When Herod arrived in Phoenicia right after his investiture by the Roman Senate, Ventidius was already there (War 1.290/1.15.3, Ant. 14.394/14.15.1), so his investiture could not have been earlier than August of 39 bc.

(5) The consensus year for Herod and Sosius’s siege and capture of Jerusalem, 37 bc, is expressly negated by Dio Cassius (History 49:23), who says that in the consular year corresponding to 37 bc, Sosius and the Roman army “accomplished nothing worthy of note” and did not engage in any activity in the region.

(6) The Sabbatical year that Josephus says was in effect during the siege of Jerusalem was shown to be 36 bc while the consensus Sabbatical-year system, built as it was on an erroneous date for the siege (37 bc), is in conflict with other post-Exilic Sabbatical years, the dates of which can be firmly established by inscriptional, numismatic, and archaeological evidence.

(7) The incoherency of the consensus chronology’s measurement of times for Herod was contrasted with the coherency, and agreement with Roman historical data, evinced by Filmer’s chronology that places the death of Herod in early 1 bc.[3] This was exhibited in the two tables at the end of the “Elapsed Times” paper.

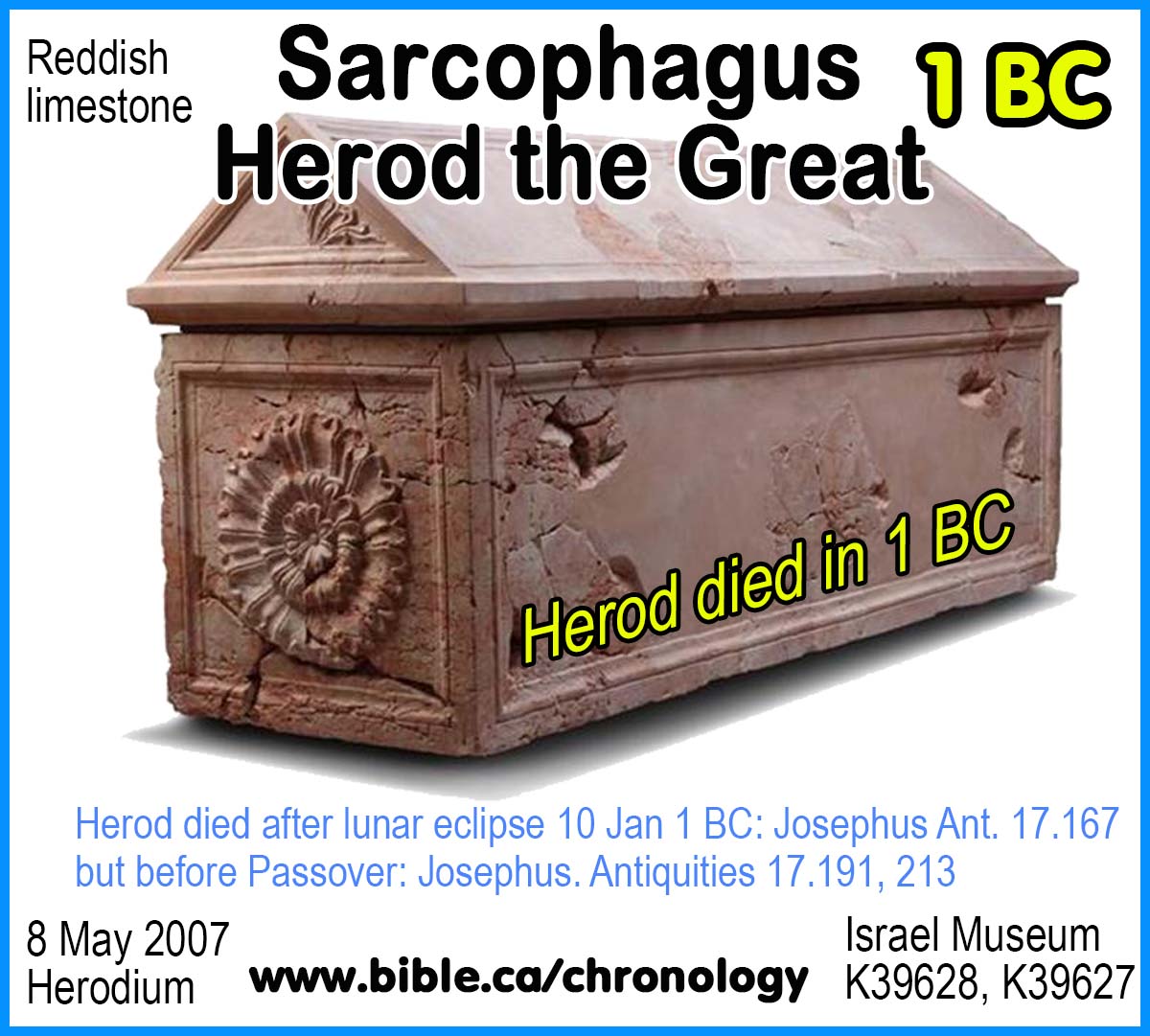

WORKING PRINCIPLES OF THE PRESENT PAPER

As a consequence of these preceding studies and the work of others in the field who have recognized the problems with the consensus chronology for Herod, certain principles will be taken as foundational when dealing with the timing of the reigns of Herod’s sons. The first such principle that was established earlier is that Herod died in the period between the total lunar eclipse of January 9/10, 1 bc, and the start of Passover on Nisan 14/April 8 of that year. Since this date is later than the numismatic and other historical evidence provides for the years to which Archelaus, Antipas, and Philip assigned their accession year, some form of antedating is indicated. The present paper will present evidence for antedating beyond this simple calculation.

In keeping with the demonstration that Herod (and Josephus when reporting on Herod) used Tishri years in determining the year of reign, the same principle will be used for Herod’s sons. Although some of the data for determining events in their reigns are necessarily expressed in terms of the Roman calendar, the tetrarchs themselves would have used the Judean Tishri-based calendar in reckoning their years of reign. This is consistent with the practice of Judean kings in the monarchic period. The work of Valerius Coucke[4] and Edwin Thiele[5] established that Judean kings always reckoned their regnal years based on a Tishri calendar. The use of the proper (i.e. Tishri-based) calendar is especially important when considering the numismatic data.

WHAT IS AN ACCESSION YEAR?

It has been our experience that many who write on historical matters have a lack of understanding about some fine points regarding the means by which those in authority in the Ancient Near East measured their years of reign. Although there were some long-term eras such as the Roman Anno Urbis Conditae, the Greek Olympiads, or the Seleucid Era, for the time and the individuals that are the subject of the present study the most important temporal metric was the year of reign or service. This was used for Israel’s high priests, kings, ethnarchs, and tetrarchs. There are thousands of records of legal contracts and other matters over a period of many centuries that used this method. It is found repeatedly in the writings of Josephus. It was personally used by Herod and his successors, as is evident from the year-dates on their coins. It is therefore essential to understand some technicalities regarding just how these individuals understood that reign lengths were to be measured. Those technicalities were well understood by Herod, Josephus, and their contemporaries, including those who made legal contracts, and it is incumbent on modern historians to determine just what their understanding was.

The first observation is that the years of reign were not “factual,” which is a term applied to the situation where counting for the years of reign was determined from the exact day on which someone took office.[6] Instead, the years were incremented when a new calendar year officially began. For Judea in the time of the Herodians this was on the first of Tishri. It has already been stated that the Greek terminology used by Josephus in Ant. 1.81/1.3.3 makes this explicit. It is also borne out by other contemporary historical considerations.

The remaining problem, then, has to do with how the partial year in which the individual took office was counted: Was it his “year one,” or was it what in modern terms might be called his “year zero?” Both methods were used in the Ancient Near East. The Babylonians and Assyrians usually used the “year zero” method. However, since the mathematical concept of zero had not yet been invented, they used a phrase equivalent to “the beginning of the reign” (Akkadian resh sharutti) to refer to the partial year of reign before the official “year one” began on Nisan 1 in their Nisan-based calendar. An equivalent usage is found in 2 Kings 25:27: “in the year Evil-Merodach became king of Babylon.” Coucke and Thiele recognized that both methods were used in the Hebrew monarchic period, with the “year zero” method usually called the accession method and the “(partial) year one” method called the non-accession method.

Since the “year one” method counts the initial partial year as a full year, this kind of reckoning is also called inclusive counting. It is the method that is essential to the consensus chronology of the reign of Herod. In this method, the initial year gets counted twice, once for the dying or replaced ruler and once for his successor, whereas using the accession method there is no such duplication of counting. That non-accession or inclusive numbering was not used by Josephus should have been established when Filmer analyzed the list of reigns of the high priests from Simon to Aristobolus as given by Josephus, after which Filmer concluded, “If each of these reigns had been reckoned by the non-accession-year system, the total would have exceeded the actual period by six years, and the fact that it does not do so proves that Josephus used the accession-year system.”[7] It is unfortunate that despite Filmer’s clear logic and the added examples from subsequent investigations, the consensus chronology, with its inclusive numbering, is still the majority viewpoint of modern scholarship. That Herod personally used the accession system is shown from his “year three” coins, as will be discussed below.

In what follows, then, the first partial year of any of the Herodians will be referred to as their “accession year,” and it is understood that this is the partial year that preceded what technically should be called their “year one” in an accession-year system. Thus for Herod himself: He was named as king by the Roman Senate sometime not long after Tishri 1 of 39 bc; this is his accession year, which we write as 39t bc (accession), the “t” after the bc year indicating that Judean regnal years, starting in Tishri, are intended. His official “year one” was then 38t and “year 3,” the year in which he captured Jerusalem and issued his year-three coins, was 36t bc, i.e. the year that began on Tishri 1 of 36 bc and which saw the fall of Jerusalem to Herod and Sossius nine days later, on the Day of Atonement.

EVIDENCE FOR ANTEDATING BY HEROD’S SONS IN THE WRITINGS OF JOSEPHUS

Several passages in Josephus shed light on the authority exercised by Herod’s sons during the final years of their father’s reign. First, Josephus reports that during Antipater’s trial Herod testified before Varus that:

I confess to you, Varus, the great folly of which I was guilty. For I provoked those sons of mine to act against me, and cut off their just expectations for the sake of Antipater. Indeed, what kindness did I do them, that could equal what I have done to Antipater, to whom I have, in a manner, yielded up my royal authority, while I am alive, and whom I have openly named for the successor to my dominions in my will…[8]

In effect, Herod testified that Antipater was not only his successor, but his co-regent. In his reply and defense to his father Antipater made the same claim:

Indeed, what was there that could possibly provoke me against you? Could the hope of being king do it? I was already a king. Could I suspect hatred from you? No. Was not I beloved by you? And what other fear could I have? No, by preserving you safe, I was a terror to others. Did I lack money? No, for who was able to expend so much as myself? Indeed, father, had I been the most execrable of all mankind, and had I had the soul of the most cruel wild beast, must I not have been overcome with the benefits you had bestowed upon me? Whom, as you yourself say, you brought; whom you preferred before so many of your sons; whom you made a king in your own lifetime, and, by the vast magnitude of the other advantages you bestowed on me, you made me an object of envy.[9]

Antipater’s frustration about not being legally named coregent that Josephus discusses at the beginning of Antiquities 17 appears to confirm this. Therefore, Josephus’s consistent concern in Antiquities 16–17 about the position of Herod’s sons in succession to their father lends credence to the statements about Antipater’s position as “already king” in Jewish War 1. These statements are made during speeches reported by Josephus, and therefore not to be taken as verbatim quotes. Josephus may have invented the speeches of Herod and Antipater, but his source in this matter was Nicolaus of Damascus, who was present at, and participated in, Antipater’s trial. Although in the Graeco-Roman literary tradition, authors were expected to show their rhetorical skill in crafting speeches for their characters, any deviation from the basic circumstances and facts would reflect poorly on the author. One such basic item of information is that Herod, while still living, had indeed yielded some of his authority to Antipater.

Unlike the consensus chronology, where the three sons of Herod must start their reigns at exactly the time when their father died, such a coincidence of starting years is not essential to the view that they antedated the start of their reigns to a time before their father’s death. They could be reckoning to different events and times, as long as the times were before the death of Herod in early 1 bc. If, however, it is conjectured that they began their reigns when their ill-fated half-brother Antipater was granted authority by Herod, then the years from which they measured their reigns could be used to date more closely the pinnacle of Antipater’s career. That Herod assigned royal status to his sons during this time is suggested by a passage in War 1.461/1.23.5 where, according to Josephus, Herod declared “I am not giving away my kingdom to my sons, but only give them royal titles; by which they may enjoy the easy side of government as princes, while the burden of decision rests upon myself whether I want it or not.” The context of this remark places it in the time when Herod was still in good health, which was before the trials of Alexander and Aristobolus and the later death of Herod’s brother Pheroras. Determining the year to which Herod’s sons antedated their reigns will allow us to date more exactly the acme of Antipater’s career and the subsequent events related to his downfall. The granting of royal titles to the three sons, added to the prerogatives that Antipater was exercising at this early date, would offer an incentive for Archelaus, Philip, and Antipas to maintain that their own authority began at that time.

WHEN DID ANTIPATER EXERCISE AUTHORITY UNDER HEROD?

Antipater’s appointment as successor to Herod is related in War 1.573/1.29.2 and Ant. 17.52/17.3.2. In both passages, Josephus relates that in Herod’s will, should Antipater predecease Herod, then Philip would be Herod’s successor. This declaration by Herod’s in his will reasonably marks the beginning of the time when Antipater reckoned that he “was already a king,” and when the other three sons were given royal titles. The present study shows that Herod’s three sons antedated the beginning of their reigns to sometime in the Judean year that began in Tishri of 6 bc, which is a likely candidate for the time of these events.

After the death of both Antipater and Herod, it would not be unreasonable to propose that Philip, motivated by the timeless principle of sibling rivalry, assumed that when Herod named him as successor to Antipater, the death of Antipater merited his claiming the same rights that Antipater claimed before he was disgraced and put to death. It does not seem unreasonable that Archelaus and Antipas would have followed suit, each not to be outdone by their sibling.

THE LACK OF COINS OF ANTIPATER

Although Josephus, and apparently his source Nicolaus, relate that Antipater boasted of all the authority he initially enjoyed under his father Herod, no coins have been found with his name. As long as his father Herod was alive, this is one prerogative that would not have been shared; any coins issued would bear Herod’s name as long as he was alive, not that of his son no matter how many other responsibilities were shared. The importance of this in explaining why Antipas and Philip have no coins dated to their years 1, 2, and 3 will be developed after examining the dated coins from the reigns of these two other sons of Herod.

THE REIGN OF HEROD THE GREAT: 39T BC (ACCESSION) DE JURE, 36T DE FACTO, DEATH 2T BC

The pivotal dates for Herod were his investiture as king, his capture of Jerusalem, and his death, in 39t, 36t, and 2t bc respectively.[10] These dates, originally proposed by Filmer,[11] were confirmed in detail in the two previous studies of this series.[12] Unlike the consensus dates for Herod, they are consistent with the Roman consular years for Herod’s appointment as king by the Romans and later siege of Jerusalem as found in Appian and Dio Cassius. They are also in agreement with the correct sequence of Sabbatical years for the time, that of Ben Zion Wacholder.[13] Since the two previous studies present multiple reasons why the death of Herod was in early 1 bc (Judean regnal year 2t bc), that date may be considered one of the two foundations for the case that Herod’s sons antedated their reigns. The other foundation is that Herod’s sons dated their reigns from some time before Herod’s death, as was mentioned above and will be discussed further below.

THE COINS OF HEROD THE GREAT

Most of coins issued by Herod were undated. The exception is the series of coins issued under his authority that contain a date: year three.[14] These consist of four denominations of coins, each with the inscription ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΗΡΩΔΟΥ, “of King Herod.”[15] Nearly everyone considers these coins to have been issued during Herod’s first year as king after his conquest of Jerusalem.[16] This has been challenged most prominently by Meshorer, who noted that a ligature on all four coin types appears to be a Greek tau and rho superimposed on each other.[17] Meshorer proposed that this ligature proclaimed Herod as tetrarch, a position granted him by Antony some time before the Roman Senate proclaimed Herod king. Thus, according to Meshorer the “year three” inscription refers to Herod’s third year as tetrarch, not his third year as king.

Meshorer’s proposal has met with little support, and for good reason: Not only is there no known ancient source that reckoned Herod’s reign from his appointment as tetrarch, but it makes little sense for Herod to proclaim himself as king on his coins and then draw attention to the lesser rank of tetrarch. Richardson and Fisher discuss this ligature:

There are at least nine different scholarly interpretations of this ligature, some more fanciful than others, the likeliest explanation being the monogram of someone involved in the minting. The monograph is not Herod’s own, for the inscription already makes clear that the coins are his. Rappaport suggests that this must be the monogram of the mint master, while Ariel and Fontanille suggest it is the monogram of the magistrate responsible for the issue of the coin, who had direct supervision of the production of new coin issues; his monogram would be a sort of quality control stamp. Ariel and Fontanille note “unidentified monograms and abstract symbols were the rule, not the exception. Since we know very few of the names of magistrates in the southern Levant, we are unlikely to discover this person’s identity.”[18]

However, Kanael has suggested that the ligature is a contraction for trito, third year, arguing that Herod may have wanted to accentuate that his first year in Jerusalem was to be regarded as his third year as king.[19] In support of Kanael’s theory is the fact that both the 2 protot and 1 prutah denominations exist without the date and ligature. Removing the date—perhaps for issues in subsequent years—would not have necessitated removing the ligature if the ligature was merely a mint mark.[20] However, no matter what the meaning of the tau-rho ligature, the most likely explanation of the inscription “year three” is that it denotes year three of Herod’s reign as king.

Yet this raises the question of why Herod first issued coins in year three of his reign. Moreover, since these are his only dated coins, year three appears to be significant. The explanation for this is that Herod was reckoning his years on the throne beginning from his appointment by Antony and the Senate, and three years after that investiture saw his conquest of Jerusalem.[21] Therefore, Herod antedated his reign to his de jure authority (according to the Romans) instead of using the de facto date of his reign in the year that he conquered Jerusalem. This choice of dating was most probably for propaganda purposes. Fontanille and Kogon note:

A ruler may have one or more of several reasons to mint coins. Coins could be minted to finance wars or construction projects. While coins were not usually struck solely for propaganda, they were still used to disseminate it. Inter alia, coins could also be used to mark a ruler’s autonomy, symbolize his strength, mark notable travels, and commemorate military victories or the founding of a city.[22]

As far as is known, the only significant year three of Herod would have been the beginning of his reign in Jerusalem. Thus, Herod left a precedent for his sons to follow, and they, too, might possibly have antedated their reigns to a time before their de facto assumption of power. Their coins bear witness to that practice.

Further, the “3” on the coin must be taken in a non-inclusive sense if it is marking the year in which Herod captured Jerusalem. The consensus view, which believes that Herod counted his years in an inclusive manner, would have Herod conquering Jerusalem in 37n bc (the “n” indicating a Nisan-based year), but his investiture in 40n bc. Since the consensus view contends that Herod’s year were counted inclusively (i.e., using non-accession reckoning) from his investiture, Herod’s earliest dated coin would have had to bear a “year 4” inscription. Thus, Herod’s coins provide physical evidence that he counted the years of his reign in a non-inclusive manner. The coins demonstrate that he reckoned his accession or “zero” year to be 39t bc, the year of his investiture as king, his “year one” to be 38t bc, and his “year three” to be 36t bc, in contrast to the consensus view that makes the partial year in which he was invested to be his “year one” and his “year three” to be the year before he captured Jerusalem. This is additional evidence that when the coins of Herod’s sons have a year marker, the same non-inclusive significance should be given preference, whereas most numismatists assume inclusive reckoning.

THE REIGN OF HEROD ARCHELAUS: 6T BC (ACCESSION) TO AD 5T (AD 6, ROMAN CALENDAR)

When Archelaus went to Rome to have his authority confirmed by Augustus he was opposed by his enemies. Josephus reports that they brought what appeared to be contradictory charges. One charge was that Herod did not appoint Archelaus king until he was demented and dying.[23] The other charge was that Archelaus had exercised royal authority for some time.[24] These two charges are not as contradictory as they seem. Archelaus was named Herod’s successor about four years before Herod’s death and may have exercised royal authority until a brief period before Herod’s death when he was temporarily disinherited. Then, while he was dying and many thought he was no longer of sound mind, Herod once again rewrote his will to leave the kingdom to Archelaus. Therefore, once Archelaus was confirmed as king to succeed his father, he may well have begun to reckon his reign from the time that he was initially named successor or from the time that he and his half-brothers were given royal titles (War 1.461/1.23.5).

The last year of Archelaus’s reign is given in Dio Cassius (55:27) as the consular year corresponding to AD 6, when Archelaus was banished by Augustus to “beyond the Alps.” Josephus (Ant. 17.342/17.13.2) relates that it was in the tenth year of his reign that Archelaus was banished to Vienna in Gaul. Unfortunately for Josephus’s credibility, he had stated in War 2.111/2.7.2 that the banishment was in Archelaus’s ninth year. Since Antiquities was the later of the two works, the tenth year is more likely correct, and will be used in determining the year that reckoned as his accession year, although the alternative expressed in War should be kept in mind. The narration of events in Antiquities and War suggests that Archelaus’s banishment came before the fall season of ad 6, so that his last year by Judean reckoning would be ad 5t. Assuming non-inclusive (i.e., accession) reckoning as was used by his father Herod gives his accession (“zero”) year as 6t bc.[25] The consensus view places Archelaus’ reign beginning in 4 bc immediately after Herod’s death (which is held to have occurred in Nisan of 4 bc). Thus, the consensus view would have Archelaus’ reign dated from 4n bc to ad 6n by using inclusive (non-accession) reckoning. A major difficulty with these consensus dates was mentioned in the introduction: All of the activities associated with Herod’s death cannot be fit into the period Nisan 1 to 14 of 4 bc.

The Coins of Herod Archelaus

There are six known coins issued under Archelaus, whose coins bear the name Herod and the title Ethnarch.[26] None has a date. Thus, Archelaus’s coins are of little probative value in determining the dates of his reign.

THE REIGN OF HEROD ANTIPAS: 6T BC (ACCESSION) TO AD 38T (AD 39, ROMAN CALENDAR)

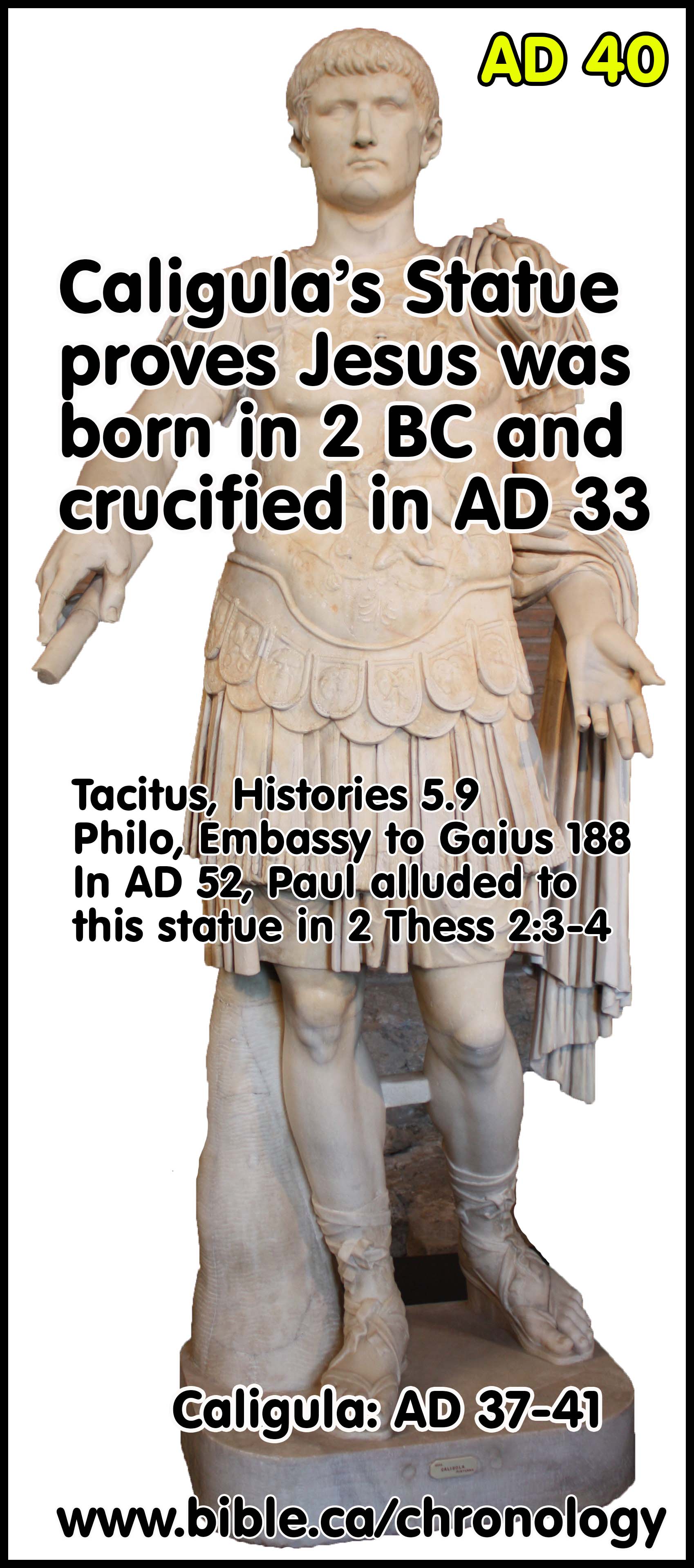

Antipas ruled the tetrarchy of Galilee and Perea (Ant. 18.240/18.7.1). His wife Herodias was jealous of the honors given to her brother Herod Agrippa, honors above those of her husband Antipas, and so she persuaded Antipas to go to Rome to seek equal honors from Gaius Caesar (Caligula). Agrippa turned Caligula against Antipas, so that Caligula banished him and his wife. This would have to be year 43 of Antipas, because he has coins dating to year 43. The banishment must have been before the fall of ad 39, because Caligula left for Gaul in the fall of that year, not returning until August 31, ad 40.[27] The encounter between Caligula and Antipas could not have occurred after Caligula’s return from Gaul (i.e., after August of ad 40), because Antipas was not involved in the trouble over Caligula’s statue for the Jerusalem temple that is related by Josephus and Philo (Legatio ad Galium) after his account of the deposition of Antipas. Therefore, taking year 43 as Antipas’s last year, we date it in the Judean system to ad 38t. Remembering that there was no year zero, this puts his accession year as 6t bc.

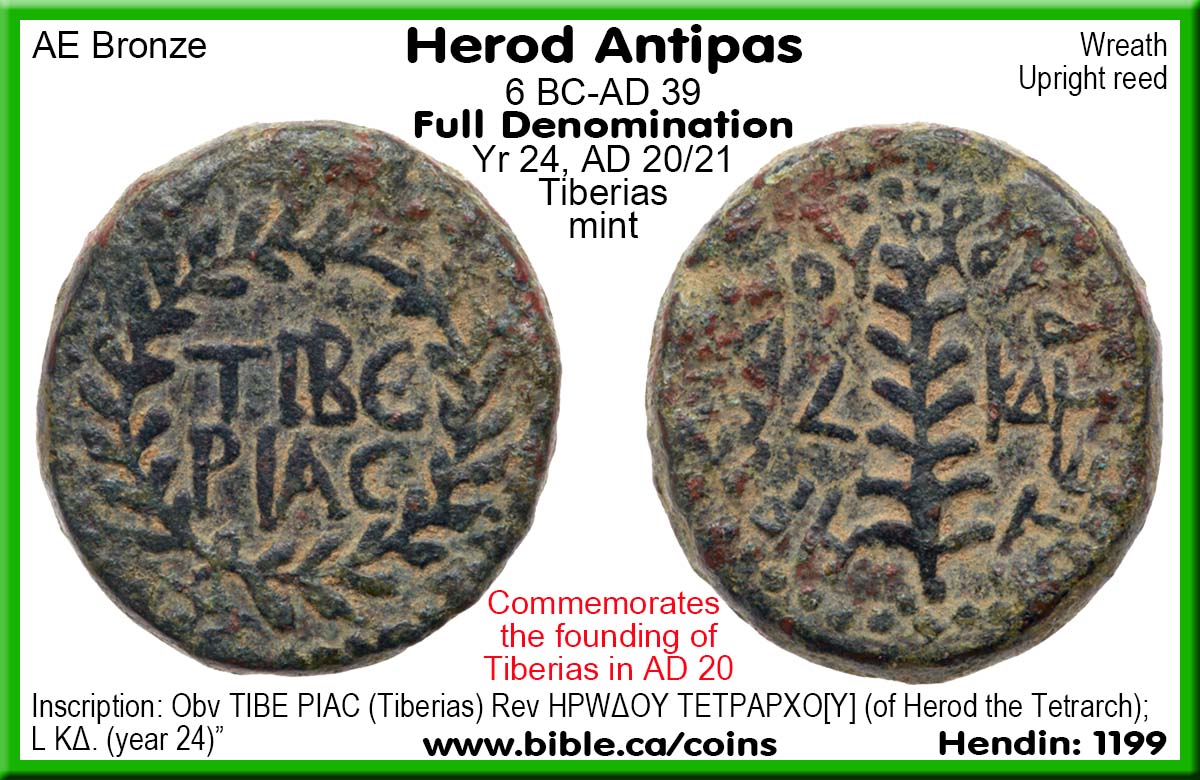

The Coins of Herod Antipas

For many years, five series of coins were known to be issued by Antipas: those of years 24, 33, 34, 37, and 43.[28] The first and last of these are especially important. The coins of year 43 come from the last year of Antipas’s reign. They were minted before his trip to Rome to see the Emperor Gaius (Caligula), who two years earlier had named Antipas’s brother-in-law Agrippa king and successor to Philip.[29] Antipas travelled to Rome in ad 39 with lavish gifts, and he intended to flatter Gaius, hoping to also be named king.[30] Part of the attempt to appeal to Gaius is shown on the year 43 coins with the inscription ΓΑΙΩ ΚΑΙCΑΡΙ ΓΕΡΜΑΝΙΚΩ, that is, “in honor of Gaius Caesar Germanicus.” As shown in the previous paragraph, this is in agreement with Antipas’s accession year as 6t bc.

Antipas’s year 24 series coins are the first to bear the inscription ΤΙΒΕΡΙΑC, “Tiberias,” in honor of the emperor. Apparently, they were issued to mark the founding of the city of Tiberias in ad 20, and once again demonstrate that Antipas dated his reign from 6t bc. The subsequent series of years 33, 34, and 37 also bore this inscription until it was replaced by the inscription honoring Gaius in the year 43 series.

More recently one example of the earliest known coin of Antipas has been found.[31] On its obverse this coin bears the inscription ΤΕΤΡΑ[ΡΧ]ΗC Δ, “Tetrarch [year] 4” with the inscription ΗΡω[Δ] (“Herod”) on the reverse.[32] Hendin has observed that this coin appears to be trial coinage [prototype] struck at Antipas’s first capital city, Sepphoris.[33] It has also been noted that this coin is unlike the later coins issued by Antipas, and more like the coins issued by his father [Herod].[34] Thus, this coin appears to have been a limited mintage—perhaps a trial—and to have been somewhat hastily executed in the style of Antipas’s father. All of this points to this as a first attempt in coinage to assert Antipas’s position as tetrarch at the beginning of his reign. But if it was a first attempt, this implies that he did not have authority to issue coinage in the three preceding years because he was still subordinate to his father Herod, who was still alive.

Considering Antipas’s obvious exploitation of the propagandistic value of coinage, this coin most likely ought to be understood to have been issued during Antipas’s first de facto year as tetrarch.[35] Like his father, Antipas was most likely using this coin to declare which year ought to be reckoned as his first. Thus, although the coin would seem to indicate that Antipas had reigned four years, it may well indicate that this was the first year he had authority to issue coinage—his first actual year as tetrarch. Considering the argument just above that he reckoned his “accession” year as 6t bc, this “year four” coin would have been issued in 2t bc, which is compatible with our thesis that Herod died in 2t bc, but his sons antedated their reigns to start four years before that time and only were able to issue coinage after their father died.

THE REIGN OF PHILIP THE TETRARCH: 6T BC (ACCESSION) TO AD 32T

Determining Philip’s accession year from the texts of Josephus turns out to be problematic, largely due to textual questions in the relevant Josephan passages. The first problem is whether Philip’s death was in the twentieth year of Tiberius, as given in all modern editions, or in Tiberius’s twenty-second year, as given in the many Latin manuscripts issued before ad 1544.[36] Adding to the ambiguity is whether Josephus was using “factual” years for the reign of Tiberius (i.e. dating his years from the exact date he was declared emperor by the Senate) or by calendar years starting on January 1. The total years of Philip’s reign is also called into question, with many manuscripts giving 37 years, but others giving 32 and 36 years. In light of these variables, it will be more convenient to use the numismatic data in determining the Philip’s starting and ending dates. The advantage of coins is that they are a primary source of information, unlike manuscripts that are copies of copies over periods of centuries and which are subject to intentional and unintentional scribal emendations.

THE COINS OF PHILIP THE TETRARCH

Philip issued coins in eight series, dated years 5, 12, 16, 19, 30, 34, and 37. The first issue that the coins of Philip settle is the length of his reign. His last series of coins was issued in four denominations, each inscribed on the reverse with L ΛΖ, “year 37.” These coins confirm those texts of Josephus that give 37 years for the length of Philip’s reign.

In year 19 of his reign Philip issued a coin inscribed on the obverse (in the Greek dative case) ΤΙΒ ΚΑΙCΑΡΙ ΣΕΒΑΣ, “for Tib[erius] Caesar Augustus. The reverse has the inscription ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ ΤΕΤΡΑΧΟΥ, “of Philip the Tetrarch” and the symbol L (for “year”) followed by ΙΘ, denoting year 19. It, therefore, likely commemorates Tiberius’s ascension to the imperial throne on September 18, ad 14 following the death of Augustus on August 19, ad 14. The coin was probably issued not long after news of Tiberius’s accession was received in Judea. Taking this as Judean year ad 14t would place Philip’s first year as 6t bc.[37] Thus, upon hearing of Tiberius’s accession sometime in October or November of ad 14, it is likely that Philip issued this coin late in that year or early in ad 15.

The coin of year 19 settles another issue that is problematic in the textual data. Since Philip’s year 19 was ad 14t, his 37th and final year, 18 years later, was ad 32t. This rules out Philip’s dying in the 22nd year of Tiberius as given in some manuscripts of Josephus. It is compatible with Tiberius’s twentieth year if Josephus reckoned Tiberius’s reign in a “factual” manner, i.e. reckoning Tiberius’s “year one” as starting with his declaration as emperor by the Senate on September 18, ad 14, so that his twentieth year by this reckoning began on September 18, ad 33. This overlaps Philip’s 37th year by Judean reckoning in the period September 18 to Oct 14 (last day of Elul), indicating that Philip died sometime in those four weeks. The calculation is dependent on Josephus reckoning Tiberius’s twentieth year in a factual sense rather than starting on January 1. That Josephus used this method for Roman emperors is suggested by his giving their reign lengths in the exact terms of years, months, and days rather than just years as he does for Judean rulers.[38]

In his year 34 Philip issued a coin that is inscribe on its obverse ΤΙΒΕΡΙΟΥ ΣΕΒΑΣΤΟΣ ΚΑΙΣΑΡ, “of Tiberius Augustus Caesar.” On its reverse is the inscription ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΣ ΤΕΤΡΑΡΧΟΥ ΚΤΙΣ, “of Philip the Tetrarch, founder” as well as L ΛΔ, “year 34.” This coin commemorates Philip’s refounding of Bethsaida and renaming it Livias in honor of Livia Drusilla, the wife of Augustus and mother of Tiberius.[39] Livia died on September 28, ad 29, and this coin commemorates Philip’s dedication of Bethsaida to her in the following year, which we shall take as ad 29t by Judean reckoning. Once again this implies that Philip reckoned his accession or “zero” year as 6t bc.[40]

why ARE THERE NO YEAR 1, 2, OR 3 COINS FOR the tetrarchs?

No dated coins for Archelaus have been found. The earliest known dated coin for Philip is for his year 5. The above study calculated his starting year as 6t bc, which would date the issuing of his year 5 coin to 1t bc. For Antipas, the earliest coin is for year 4. Using his starting year, 6t bc, along with non-inclusive numbering, places the issuing in 2t bc. The consequence is that Philip and Antipas minted their first coins from 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 years after the consensus date for the death of Herod.

This lack of any coins from years 1, 2, or 3 of Philip and Antipas is very problematic for the consensus paradigm for Herod. In researching the present paper, the authors have sought the opinion of internationally known numismatists regarding two questions: (1) How many dated coins are known from the two tetrarchs, and (2) Why are none of them dated from their years 1, 2, or 3?

The uniform answer for question (1): The dated coins are in many collections, public and private, around the world, and no one knows how many there are, although the number is estimated to be in the thousands. This answer provoked the following experiment. We assumed that there were only 100 dated coins from Philip, and a similar 100 dated coins from Antipas. We then assumed that the probability of Philip commissioning a dated coin in any year of his 37-year reign was equally probable with any other year, and the same for the 43-year reign of Antipas. We then asked the question: What is the probability, given this simple starting place, that no coins of from years 1, 2, or 3 of Philip and no coins from years 1, 2, or 3 of Antipas would exist? The result of this happening by chance came out as 1.06 times 10-7, i.e. one part in ten million. This strongly indicates that some factor is mitigating against the hypothesis we were testing, namely that any year of reign was equally good as any other year for issuing coins. Of course, the results would be much more improbable if we used the greater numbers (probably thousands) for extant dated coins suggested by our correspondents.

For question (2), two correspondents replied that the issuing of coins was “sporadic.” Judging by the literature, others would seem to agree with this statement. But sporadic is a term that seems fairly close to the hypothesis that the years were equally probable, and which our calculation showed was effectively falsified. The above discussion of coins strongly suggested that special events such as the accession of a new emperor were likely to bring about a commemorative coin issue, and so it might be argued that not all years were equally probable for issuing coins. But in the history of the time, those events themselves could be considered as equally probable as happening in any year of the two tetrarchs; it should have been just as probable that some notable event occurred in years 1, 2, or 3 as in any other year. In fact, there was one year that, with our knowledge of the time, was very likely to have a commemorative issue: the year in which the ruler first had the authority to issue a coin with his imprimatur. This is shown by Herod issuing his “year 3” coin in the year following his capture of Jerusalem, and it is shown by the Roman governor Coponius issuing a coin in his first year of governorship in Judea, as did two of his successors, Marcus Ambibulus and Valerius Gratus. Therefore, the argument that the issuing of coins by Herod’s sons were not actually random but were more likely to occur as commemorating some special event, presents a further difficulty to the consensus view. In that view, some explanation should be given why, in the consensus system, the sons of Herod waited until three years after the death of Herod to issue a coin commemorating the very special event of their assumption of authority.

The most reasonable explanation that we have found for the lack of coins issued in the first three years of their reign is that they did not have the authority to do so. The reason they lacked authority is because their father Herod the Great was still alive in the year to which they backdated their reigns and would live until the first part of the following fourth year (2t bc). After Herod’s death, the tetrarchs would have wanted to establish their authority by issuing coins, and that they did so is attested by the dates that have been calculated for their earliest dated coins: 2t bc and 1t bc. Both dates are consistent with Herod dying in early 2t bc, and both are consistent with the presumed desire of these tetrarchs to testify to their authority by issuing coins very soon after their earliest opportunity, as apparently their father had done. This is all consistent with the view that Herod’s sons antedated their reign to four years prior to the death of their father, a view that is required by the evidence. The consensus viewpoint that places the start of reign of the tetrarchs at the death of Herod then needs to explain why of the thousands of coins they authorized, none has a date from their first three years.

CONCLUSION

When working on the preceding papers in this series, the authors were aware that investigators who hold to the consensus position would appeal to the dates for Herod’s sons to support their position, no matter how effectively the other pillars of their construction were refuted. The shortcomings of the other pillars—Nisan-based regnal years, inclusive counting of those years, Zuckermann’s sabbatical-year calendar, and Josephus’s wrong consular years for Herod—were discussed in the previous articles as well as in Filmer’s seminal paper.[41] The acceptance of non-inclusive numbering and a Tishri calendar for Herod’s sons would require that these sons dated the start of their authority to sometime even before the consensus date for Herod’s death, 4 bc, so that some form of antedating of their reigns is required. This final paper has shown that all three sons of Herod antedated the beginning of their authority to some event or set of circumstances that took place in 6t bc. It was suggested that a possibility for such an event was Herod’s assigning royal titles to his sons at this time.

In deriving this date for the antedating, use was made of the work of numismatists who have carefully categorized and analyzed contemporary Judean and Roman coins. Of interest were the various year-stamps on the coins of two of Herod’s sons that back-dated the year to which they attributed the beginning of their authority to the same accession year that can be calculated from the histories of Josephus and Dio Cassius for Archelaus, whose coins have no year-stamps. The excellent work of the numismatists has, somewhat surprisingly to us who were novices in the field, allowed the coins to “speak out of the dust” and establish that the last pillar of the consensus chronology can no longer stand.

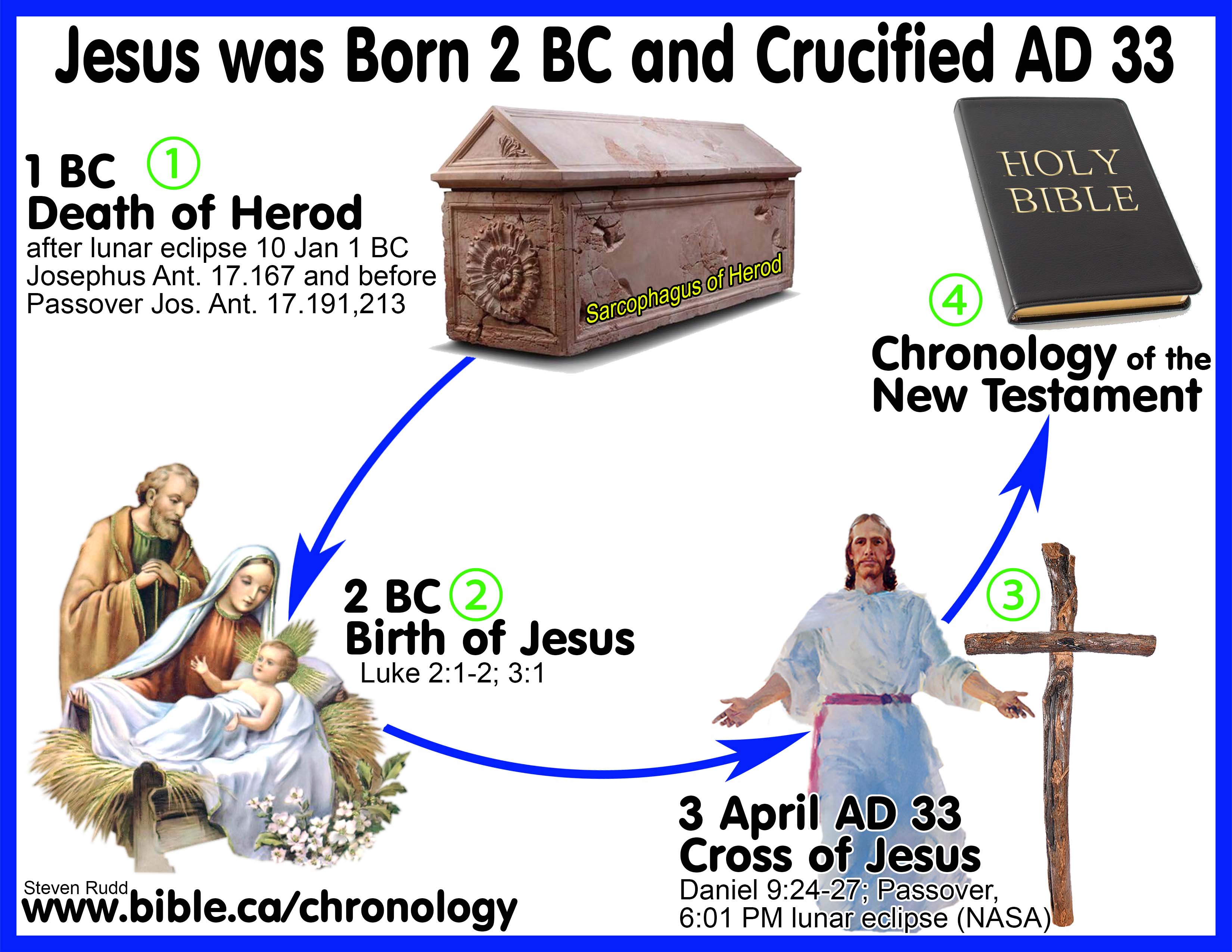

With all of the consensus pillars disproved, New Testament scholars can confidently build their chronologies on the proper date for Herod’s death, 1 bc, with consequent ramifications for the birth of Christ in late 3 or early 2 bc, as supported by virtually all early Christian authors. The further consequence is that our Lord’s death and resurrection are firmly established in ad 33 rather than at a time three years earlier [i.e. AD 30] that was supported, in part, by appeal to the consensus scholarship’s dates for Herod.

What you read in the book you find in the ground!

Uploaded by Steven Rudd with written permission: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

[1] Andrew E. Steinmann and Rodger C. Young, “Elapsed Times for Herod the Great in Josephus,” Bibliotheca Sacra (June-August 2020). Idem, “Consular Years and Sabbatical Years in the Life of Herod the Great,” Bibliotheca Sacra (Sept.-Dec. 2020).

[2] Although the succeeding paragraphs will show that Herod measured his reign in Tishri years, accepting Tishri years along with the consensus dates of Herod’s investiture and capture of Jerusalem would place his death some time in the year that started on Tishri 1 of 4 BC. This would mandate discarding Josephus’s mention of a lunar eclipse occurring shortly before Herod’s death. Although some would be willing to reject the eclipse evidence, a greater difficulty is that the reigns of Herod’s sons cannot accommodate a starting point that late. For example, the tenth year of Archelaus would then start in Tishri of ad 5; ten years earlier by non-inclusive numbering would start his accession year on Tishri 1 of 6 bc, or Tishri 1 of 5 bc if inclusive counting is used. Either figure is inconsistent with a date of Herod’s death after Tishri 1 of 4 bc that would result if the consensus chronology abandoned its Nisan calendar for the (correct) Tishri-based calendar.

[3] W. E. Filmer, “The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great,” Journal of Theological Studies ns 17 (1966): 283-98.

[4] Valerius Coucke, “Chronologie biblique” in Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible, ed. Louis Pirot, vol. 1 (Paris: Libraire Letouzey et Ané, 1928), cols. 1264–1265.

[5] Edwin Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, Zondervan/Kregel, 1983), 51–53.

[6] The Roman practice was somewhat different, since they recorded the date on which emperors acceded to the throne, and many of those dates have survived in the writings of the Roman historians. Thus, years of emperors’ reigns could be counted from day they assumed office without any need for the non-accession method to avoid double counting of years. Alternately, their reigns could be counted from the following New Year’s Day (January 1).

[7] Filmer, “Chronology:” 292.

[8]War 1.625/1.32.2.

[9]War 1.631-632/1.32.3.

[10] Herod’s investiture took place in 39t bc, that is, sometime not long after Tishri 1 of 39 bc. It is of some interest that a record has been found showing that the Roman Senate was in session a few days after Tishri 1 of 39 bc, with both Antony and Octavius present. See Joyce Reynolds, Aphrodisias and Rome (Hertford: Stephen Austin and Sons, 1992), 70, 74. Herod’s “year one” would have been reckoned from the following Tishri.

[11] Filmer, “Chronology:” 298.

[12] Steinmann and Young, “Elapsed Times;” idem “Consular Years and Sabbatical Years.”

[13] Ben Zion Wacholder, “The Calendar of Sabbatical Cycles during the Second Temple and the Early Rabbinic Period,” Hebrew Union College Annual 44 (1973): 153–96.

[14] “Year three” is denoted on the coins by the symbol “L” (for year) followed by the third Greek Letter: Γ.

[15] David Hendin, Guide to Biblical Coins. Fifth ed. (New York: Amphora, 2010), 233-34; Ya'akov Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins from the Persian Period to Bar Kokhba. (Nyack, NY: Amphora, 2001), 61-63; Ya'akov Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins from the Persian Period to Bar Kokhba. (Nyack, NY: Amphora, 2001), 61-63; Peter Richardson and Amy Marie Fisher, Herod: King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans. Second ed. (Ancient Biographies. London: Routledge, 2018), 306-10. The denominations are usually assumed to be 8, 4, 2 protot, and 1 prutah.

[16] Jean-Philippe Fontanille and Aaron J. Kogon, The Coinage of Herod Antipas: A Study and Die Classification of the Earliest Coins of Galilee. (Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity 102. Leiden: Brill, 2018), 16.

[17] Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins, 61-62.

[18] Richardson and Fisher, Herod: King of the Jews, 310.

[19] Baruch Kanael, “Ancient Jewish Coins and their Historical Importance,” Biblical Archaeologist 26 (1963): 48. Since we hold that Herod conquered Jerusalem in 36t bc three years after his appointment as king in his accession year 39t bc, his issuance of coins sometime shortly after his conquest of Jerusalem was designed to proclaim him king of Judea. That year, 36t bc, would have been his de jure year three.

[20] The reason for removing the ligature and date is not clear. However, it ought to be noted that all of the subsequent issues by Herod as well as all of the issues by his son Archelaus were undated. Leaving the coins undated may have been done in deference to the majority Jewish population who were used to mostly undated coins of the Hasmoneans (only a few Hasmonean coins were dated).

[21] Ant. 14.465/14.15.14; War 1.343/1.17.8.

[22] Fontanille and Kogon, The Coinage of Herod Antipas, 17.

[23] War 2.31/2.2.5; Ant. 17.238/17.9.5.

[24] War 2.26/2.2.5.

[25] ad 5t – 10 – 1 (no year zero) = 6t bc. 5t bc if the “ninth year” of War is correct.

[26] Hendin, Guide to Biblical Coins, 244-45; Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins, 78-81.

[27] Suetonius, Life of Caligula 8, 49.

[28] Hendin, Guide to Biblical Coins, 251-55; Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins, 81-85.

[29] Ant. 18.240-242/18.7.1.

[30] Ant. 18.246-256/18.7.2.

[31] David Hendin, “A New Coin Type of Herod Antipas.” Israel Numismatic Journal 15 (2003-2006): 56-61; Hendin, Guide to Biblical Coins, 248-50; Fontanille and Kogon, The Coinage of Herod Antipas, 9-11.

[32] It has been suggested by Goldstein that the Δ on the obverse is a completion of the name Herod, and not a year mark. (Fontanille and Kogon, The Coinage of Herod Antipas, 11). However, there are a number of reasons to discount this: 1. No known Herodian coins exhibit the continuation of a word from a coin’s reverse to its obverse (or from the obverse to the reverse). 2. Other contemporary Levantine coins at times omit the symbol L or the word ΕΤΟΥ (“year”; Hendin, “A New Coin Type of Herod Antipas:” 58). 3. It is not unusual for coins—especially small coins—to abbreviate names or titles. On this coin the title tetrarch is abbreviated by omitting two interior letters (ΡΧ). 4. All other coins of Antipas are dated.

[33] Hendin, “A New Coin Type of Herod Antipas:” 57.

[34] Fontanille and Kogon, The Coinage of Herod Antipas, 9.

[35] Note that Fontanille and Kogon, who accept the consensus view that Herod the Great died in 4 bc, are at a loss to offer a good explanation for the issuance of this coin. They can only surmise that “Perhaps the mintage of this coin type could be associated with construction at Sepphoris, which likely began around the beginning of Antipas’s reign.” Ibid., 17.

[36] See the discussion of these issues in Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology, rev. ed. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998), 301. See also Andrew Steinmann, “When Did Herod the Great Reign,” Novum Testamentum 51 (2009): 23-24.

[37] ad 14t – 19 – 1 (no year zero) = 6t bc.

[38] Josephus reckons the length of reign in this way for the following emperors: Augustus (War 2.168/2.9.1), Tiberius (War 2.180/2.9.5), Gaius (Ant. 19.201/19.2.5), Claudius (War 2.248/2.12.8 and Ant. 20.148/20.8.1), and Nero (War 4.491/4.9.2). The textual problems with some of Josephus’s figures do not invalidate the principle that he was trying to measure their time of reign in a “factual” or exact sense.

[39] As stipulated in Augustus’s will, Livia had been adopted into the Julian family and given the title Augusta. She then became known as Julia Augusta. While the city was generally known as Livias, Josephus always calls this city Julias, since he calls Augustus’s wife Julia, never Livia.

[40] ad 29t – 34 – 1 (no year zero) = 6t bc.

[41] See not only the two previous papers in this series, Steinmann and Young, “Elapsed Times,” idem, “Consular Years and Sabbatical Years,” but also Rodger C. Young and Andrew E. Steinmann, “Caligula’s Statue for the Jerusalem Temple and It’s Relation to the Chronology of Herod the Great,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 62 (2019): 759-73 and Steinmann, “When Did Herod the Great Reign?”