Editions

of the Greek New Testament

The Integrity of the New Testament - Special 2013 Series

[From The Editors: This article is one of a series we are running this year.

The 2013 series is called "The Integrity of the

New Testament" and deals with textual criticism. Can the New Testament be

trusted? Has it been corrupted through time? Can we know what God has said? It

should be obvious how important this topic is. This is especially so given the

climate of society today and its attitudes toward the Bible. We wish this

series to help everyone understand the process of the Bible's history as a

document and why we can have confidence in its message. Near the end of the year

we are planning to publish these twelve articles in book form (Kindle, Nook and

old fashioned print and ink).

The average person in Jesus’ day knew how to “put new wine into fresh wineskins, and both are preserved" (Mat 9:17). To preserve most things is relatively easy, even for man. I have often thought about the fact that the books of the NT were written on perishable papyri. Papyrus is basically a tall grass. Even though, “the grass withers, the flower fades”, yet, “the word of our God stands forever” (Isa 40:8). How ironic that God’s word was placed upon grass (papyri) and the grass withered, but the words written on it did not. Why not? Because each generation that followed, put new ink into fresh writing material and much was preserved, actually too much material for the common man. Today there are over 5800 Greek manuscripts or fragments of manuscripts to read, to date, to categorize, and finally to put in some sort of family tree. There are about twice as many Latin manuscripts as there are Greek.

It would take about 150 animal hides and seven miles of text put end to end to produce one Latin Bible. Goderannus, a scribe, did this for the second time in his life in 1097AD. He put in a note in this manuscript that it took himself and a colleague four years to make this one manuscript (De Hammel, 2001). These Bibles were almost exclusively used in monasteries and church buildings. It is about 1140AD when the Bible could be commonly purchased (ibid. p.87). Men from the first century have dedicated themselves in preserving the great treasure of the scriptures in their own language. I thank God for these men, and those who followed.

Which manuscripts should be used and compared on which to base a printed Greek text? With so many manuscripts, it is no wonder conscientious and truth seeking scholars do not always agree on which set manuscripts should take priority. Limited in scope, I will briefly deal below with the printed editions of Erasmus, the Textus Receptus, Westcott and Hort, the Majority text, and the Nestle Aland - United Bible Society editions. My main objective will be to let the general reader, who is not an expert in textual matters, get a sense on how to view these editions.

Prior to the invention of the printing press which took place in about 1450 AD, there were no editions of the Greek New Testament. If you happened to live in Western Europe and were fortunate enough to have access to a hand written Greek NT manuscript, it probably would be no more than a curious glance because, “the Bible” was the Latin Vulgate. It is worth pausing to consider that the language of the first printed Bible was in Latin, not Greek or English. The printed Vulgate Bible was being “... sold at the 1455 Frankfurt Book Fair, and cost the equivalent of three years' pay for the average clerk” (Kreis, 2012). Then, after sixty years of the Vulgate being produced in several different printings by different scholars, in 1516 AD Erasmus’ Latin text was also printed, and alongside of it, his Greek text of the NT.

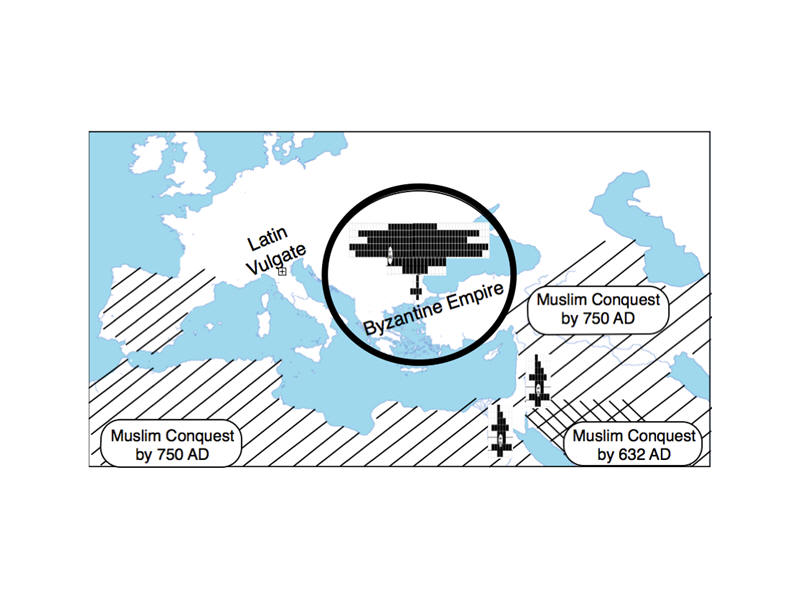

What eventually brought about a need to have a printed edition of the Greek New Testament? There are at least three factors that come into play. First of all, Greek scholars and Greek manuscripts had been fleeing from the Muslim conquest of Byzantium. “Constantinople fell to the Muslims in 1453... Greek-speaking refugees escaped some bringing books. For the first time, early Greek manuscripts became in quantity in the West” (De Hamel, 2001). Secondly there was an academic need that was growing stronger in Western Europe, i.e. the renaissance (1300 - 1700 AD). This need was not purely academic, but if one were to correct some of the erroneous readings imbedded in the Latin Vulgate, it would have to have a justifiable basis, so Erasmus turned to the underlying Greek text for his justification. Thirdly, the printers or those who sponsored a book had to see a market for their book before they would risk the high price of publication. The Greek New Testament fell short in this regard, for it was simply added on the opposing column, to “accompany and support” Erasmus’ own revision of the Latin Vulgate. Nevertheless, the Greek text finally came off the press, and to the public. The public forgot about his revision of the Vulgate and held onto his Greek printed text. We will pick up with Erasmus after we overview the Greek manuscript text types.

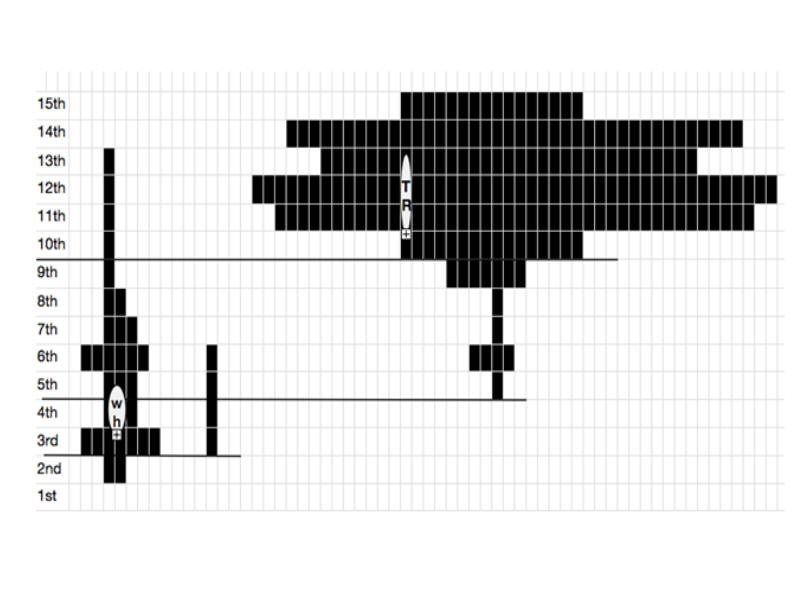

The chart below is a limited summary of the Greek manuscript tradition at a glance. I will be referring back to chart 1 in the paragraphs below so it is worth taking a moment to familiarize yourself with it. There are about 1000 manuscripts placed in this chart, most of them in the M group. For more information about the basis of this chart see the end note “chart 1”.

Based upon similar readings we have three groups or families of manuscripts. On the left we have the centuries listed, from the 1st century to the 15th. The A group of manuscripts is seen from the 2nd century to the 13th; the W group is from the 3rd to the 6th; and the M group is from the 5th to the 15th as charted.

A W M

Which group is more accurate?

Now

beginning with this next step scholars disagree, and a few of them very sharply.

Which manuscripts should be considered in comparing or collating for printing a

Greek text? “A” group goes back to the 2nd century, “W” group to the 3rd, and

“M” group to the 5th century. So as you look at the chart, what group of

manuscripts would you choose that most accurately reflects the original

writings? Would you choose group A, W, M, or a subset of A, the WH; or a

subset of M, the TR? Your answer? ___ Would you like more information before

choosing? Of course. Yet, in fact you have most likely already chosen without

realizing it. Our English versions are based upon different manuscripts and

different Greek Texts generally. If you are reading the King James Version or

the NKJV, you are reading a NT translation based on the TR, the Textus Receptus,

which was formed by comparing a handful of manuscripts in group M, see the much

smaller subset, “TR” located in chart 1. If you are reading the 1901 American

Standard Bible, you are reading a translation based upon a merger of at least

two previous Greek Texts, one of Westcott and Hort and secondly of Tregelles

(Comfort, 2008). This text would be located in group A. The Westcott and Hort

text is based predominately upon two fourth century manuscripts of high standing

of group A, along with other early manuscripts. If you are reading the New

Testament in NASB, NIV, or the ESV you are reading a translation based upon

manuscripts that are found in group “A” for the most part. Now let me assume

that you have spent time in a Bible class where these different translations

have been used. If so, you realize already the general differences that are

displayed in these two groups of manuscripts (group A & the smaller subset TR)

are not so different that you cannot follow along while another is reading from

a different version, though sometimes there are differences. The differences you

are reading in English are most often the difference in the English vocabulary

rather than the difference between Greek words. The third and smallest group of

manuscripts is known as the Western text, “W” in chart 1. There is no commonly

used English version based upon this free and paraphrastic text. The Greek

manuscript tradition of the Western text died out when the Vulgate became

popular which replaced it in the West as it retained some of its readings.

Why did the M group begin to have so many copies beginning with the ninth century? Why did group A begin to dwindle out in the ninth century?

By 632AD the Muslims had conquered much of the Arabian Peninsula. By 750AD they expanded greatly as the map shows. It is not hard to understand what transpired when the Muslims invaded Palestine and Egypt; those churches became much smaller and under duress. Therefore the Alexandrian type of text dwindled along with the churches in those regions. Also notice that the Byzantine Empire withstood the Muslim invasion, from 750AD to 1453AD. It is no wonder we have an abundance of manuscripts from Byzantium in this later period. The Byzantium text type is also known as the Majority text; in chart 1 is labeled the M text.

Having overviewed the textual tradition, we return once more to Erasmus. What manuscripts were available to Erasmus back in 1516AD to base his Greek Text upon? Erasmus had a half a dozen manuscripts to compare in producing his printed Greek Text which became the standard Greek Text. “Erasmus had 3 manuscripts of the Gospels and Acts; 4 manuscripts of the Pauline Epistles; and only 1 manuscript of Revelation.”(Combs, 1996) These manuscripts date back to the 12-15th century generally. The King James translators relied heavily upon the Greek text of Erasmus but not solely on Erasmus. They also had another printed Greek Text to rely upon, that of Theodore Beza, his 1598AD edition. So all together they translated from a Greek text based upon about 25 Greek manuscripts (Lewis, 1982). These 25 Greek manuscripts are not old, but generally go back to the 12th-15th centuries. Yet these were the manuscripts available and accessible to the translators of the KJV. After the KJV was completed in 1611AD the Textus Receptus was printed, twenty some years later, in 1633AD. The two Elzevir brothers, who were printers, published a convenient edition of the Greek NT with a “blurb” that read, “the text now received by all, in which we give nothing changed or corrupted” (Metzger & Ehrman, 2005). From this point on it was the text received by all, the “Textus Receptus”. This same text was reprinted by many thereafter with each scholar’s personal notes. “As it happened, Stephanus’ third edition became for many persons, especially in England, the received or standard text of the Greek Testament” (Metzger & Ehrman, 2005).

More Ancient Manuscripts, after the King James Version:

After the completion of the KJV there were many manuscripts being found and compared to this standard text, the Textus Receptus. Some of these manuscripts were almost 1000 years earlier. Scholars continued to print the Textus Receptus, but adding more and more of their notes that referred to older readings of earlier manuscripts. As time and manuscripts began to accumulate more editions came out, but no one was willing to print a different Greek Text than the Textus Receptus. John Mill produced a Textus Receptus that had 30,000 variant readings from 100 manuscripts; the text was printed around 1707AD. But it was Karl Lachmann in 1831 who finally took courage to dethrone the Textus Receptus and print a different Greek Text from the wording found in the manuscripts of the 4th century. By the mid-1800’s we have arrived at a critical period where scholars, almost universally, were willing to abandoned the late manuscripts of the Textus Receptus and begin to invest in the early manuscripts of group “A”, the Alexandrian type of text. Men such as Griesbach (1745-1812), Tregelles (1813-1875), and Tishendorf (1815-74), were convinced that the older manuscripts contained the readings that were closer to the originals. This took time, investigation, and affirmation to the next generation who were reluctant to leave their KJV and its underlying Textus Receptus.

Westcott and Hort:

“The year 1881 was the marked by the publication of the most noteworthy critical edition of the Greek Testament ever produced by British scholarship. After working about 28 years on this edition (from about 1853 to 1881), Brooke Foss Westcott (1825-1901)... and Fenton John Anthony Hort (1828-92)... issued two volumes entitled The New Testament in the Original Greek”(Metzger & Ehrman, 2005). Professor Hort wrote the introduction by which he laid down the principles and method they used in producing their Greek Text. These same methods are being used today. They realized that ten manuscripts could simply be copied from one manuscript. Therefore the ten copies should be treated as one witness, not ten. They also put manuscripts into large groups like chart 1 above, although they used different names for these groups, as well as one additional grouping. Also it was understood that when later scribes who had two exemplar manuscripts before them, they often did not like choosing between two different readings. So, instead of choosing, they often put them together into a longer reading. Then that longer reading was copied for the next generation. There were many other observations that Hort made in his introduction that greatly aided the next generation of scholars.

In the end, Westcott and Hort took two highly valued manuscripts, the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, both located in the “A” group above, and where these two manuscripts agree was the basis of their Greek text, for the most part. Philip Comfort writes, “In my opinion, the text produced by Westcott and Hort (The New Testament in the Original Greek) is still to this day, even with so many more manuscript discoveries, a very close reproduction of the primitive text of the New Testament. Of course, I think that they gave too much weight to Codex Vaticanus alone, and this needs to be tempered. This criticism aside, the Westcott and Hort text is extremely reliable. I came to this conclusion after doing my own textual studies. In many instances where I would disagree with the wording of the Nestle/USB text in favor of a particular variant reading, I would later check with Westcott and Hort text and realize that they had often come to the same decision. This revealed to me that I was working on the same methodological basis as they. Of course, the manuscript discoveries of the past one hundred years have changed things, but it is remarkable how often they have affirmed the decisions of Westcott and Hort” (Comfort, 2005). One of the manuscripts found since Westcott and Hort is P75, that is papyri 75, dated about 175-200AD which reads extremely close to Vaticanus, pushing the text of Westcott and Hort into the 2nd century AD and in many ways affirming that Westcott and Hort were correct in their underlying assumptions. Westcott and Hort do not mention the papyri manuscripts, which today number up to 127. They used about 45 Uncial/Majuscule manuscripts (which are written in all uppercase letters written upon parchment or velum), whereas today there are over 290 (Clarke, 1997). Also, early manuscripts written in other languages, as well as more accurate Patristic quotations have been supplemented since Westcott and Hort.

The Majority Text:

There have been a few scholars who disapprove of going to the early manuscripts, those dated from the second century to the middle fourth century, to find the basis for a printed Greek Text, the “A” group. They would rather pick the manuscripts from the M group in chart 1. These scholars realize that this M group or Byzantine type of manuscript is found only in the beginning in the 5th century, prior to that there is no Byzantine type of manuscript which has survived. So the name “Majority Text” is a misnomer in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries. The “A” type of text in chart 1, the Alexandrian type, is in fact the majority text early on, but today no one calls the Alexandrian text the majority text. So what is called today as the Majority Text is the minority text until about the 9th century, please see chart 1. Daniel Wallace further states, “So far as I am aware, in the last eighty years every critical study on patristic usage has concluded that the Majority text was never the text used by the Church Fathers in the first three centuries. (2) Though some of the Fathers from the first three centuries had isolated Byzantine readings, the earliest Church Father to use the Byzantine text was Asterius, a fourth-century writer from Antioch” (Wallace, 1995).

There are two Greek Majority texts that have been printed, one done by Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad, The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text, 1982 and one done by William G. Pierpont and Maurice A. Robinson, The New Testament in the Original Greek According to the Byzantine/Majority Textform, 1991, updated 2005. Many of these scholars who endorse the Byzantine text do so on the basis of a theological argument, that God providentially had this type of manuscript available to more people throughout history. But in making such an argument they gloss over the period from the 2nd century to 8th century where this text was not providentially the majority.

The NA26/27 and UBS3/4 editions of the Greek Text:

Most college students for the past couple of decades have been using the United Bible Society text (UBS), of the 3rd (corrected) -1983, or 4th edition -1993, or the Nestle-Aland text of the 26th -1979, or 27th edition -1993. These four editions have exactly the same Greek wording, the same Greek text. The punctuation is different between these two editions, the textual notes are very different, but the Greek words are exactly the same. The Nestle-Aland27, abbreviated NA27, cites about 15,000 variants in the text and is a more scholarly edition in the apparatus, that is in its footnote-like section on the bottom of each page. That may seem like a lot of variants, but I will put this into perspective later on. The apparatus cites key manuscripts that support the text or supports a variant that didn’t make it into the printed text. In contrast the UBS Greek text has only about 1400 variants in its apparatus, and although this apparatus cites far fewer variants, each variant is given more manuscript information.

This Greek text, NA26/27 and UBS3/4, is based upon manuscripts found in Group A for the most part, the Alexandrian text-type. This text has been the starting point for many modern versions (ESV, NASB, NET, NRSV, etc.), though each version does not follow this Greek Text completely.

It also should be noted that there are a few sections in this Greek text that have been enclosed with double brackets [[ ... ]]. These sections indicate, “that the enclosed words, generally of some length are known not to be a part of the original text...” (UBS, intro. p.2). Some of these include the account of the adulteress (John 7:53-8:11), the ending of (Mark 16:9-20), the angel and sweat like blood in (Luke 22:43-44) and the confession of the Ethiopian (Acts 8:37). Different English versions treat the above passages differently, some simply place a marginal note showing the text has weak or only late manuscript support, others put some of these texts in the side margin, others put [ ] brackets around the text identifying to the careful reader that this portion of the text does not have early manuscript support.

The goal of the UBS Greek Text has been towards translators “throughout the world”. In this regard, it notes the variants that would possibly make a difference in translation. Most variants do not affect translation at all as you will see shortly. The UBS3 edition cites 1444 variants, the USB4 cites 1438 variants. The USB4 has removed 273 variants and added 284 new variants. The UBS apparatus gives each variant reading a rating of either, A, B, C, or D as a guide for the certainty of the text. Where “A” indicates that the text is certain, “B” indicates that the text is almost certain, “C” indicates that the committee had difficulty in deciding which variant to place in the text, and “D” indicates that the committee had great difficulty arriving at a decision (UBS, intro. p.3).

It is rather interesting that there has been a “textual optimism” growing from the UBS third corrected edition in 1983, to the UBS fourth edition in 1993, for the graded text. This means that there are far more “A” ratings in the 4th edition than in the 3rd edition, showing more certainty by its editors. Kent Clarke explores the reasons for this dramatic upgrade in the certainty of the text as he looks for the manuscript evidence cited in both editions. Note the dramatic increase of A’s and the dramatic decrease of “C”s and “D”s from the third edition to the fourth edition.

UBS3 has 126 “A” ratings, the USB4 has 514.

UBS3 has 475 “B” ratings, the USB4 has 541.

UBS3 has 669 “C” ratings, the USB4 has 367.

UBS3 has 144 “D” ratings, the USB4 has 9. (Clarke, 1997)

It is obvious that from 1983 to 1993 the members of this committee, which has seen some change in membership, have become more confident in this printed Greek text. This is encouraging to observe the growing confidence of these textual scholars. The explanations for this growing optimism between the 3rd corrected and 4th editions have not been explained very adequately according to Kent Clarke.

Getting a Perspective

Now that we have briefly highlighted the history of Textus Receptus, Westcott and Hort, Majority Text, and the NA26/27 and UBS3/4 editions of the Greek Text, let us get a perspective on the differences. My BibleWorks computer software will in just over a second compare all the differences between these four different Greek Texts. Let us take brief look to see how similar these four Greek Texts are. In the chart below I will look at all the differences between these four texts in Matthew chapter one only. Mathew chapter two has fewer variants than chapter one.

In the chart below the TR = Textus Receptus, M = Majority Text of Robinson-Pierpont (1995), WH= Westcott and Hort, NU= NA26/27 and UBS3/4 editions of the Greek Text. Matthew chapter one has 25 verses. In the first chart below all the verses that have the same exact wording for all the words in each verse, and the number of Greek words in that verse. I will not include the moveable “nu” that looks like a “v”, as a difference, for this is a common difference in spelling only. This is not to say that there are not variants in these verses below because there are some, but rather these five committees using different sets of manuscripts have concluded that this represents what the initial text according to the set of manuscripts they used. NU represents two committees, that of the Nestle-Aland text (N) and that of the United Bible Society (U).

Mat. 1:2 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 18 words

Mat. 1:3 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 21 words

Mat. 1:4 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 15 words

Mat. 1:12 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 14 words

Mat. 1:16 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 15 words

Mat. 1:21 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 19 words

Mat. 1:23 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 22 words

Remember the manuscripts for the TR come from about 25 manuscripts from the 12-15th century generally. The Majority text comes from the manuscripts beginning from the 5th century to the 15th century. The WH text comes from a few manuscripts from the 4th century and a few additional manuscripts located mainly in the Alexandrian family. The NU text is also from the Alexandrian family now supported and supplemented with the additional papyri. This shows that the Greek Text is far more consistent through the centuries than some might think. Secondly, this shows that the Greek Text in these five editions in these verses above is the same, but our English translations use different English vocabulary in these verses. The variety in English translations in the above verses is the English, not the Greek.

Now we will look at the differences of these five Greek texts from Matthew chapter one. You may want to just skim over these, but it does give you an idea of how close these Greek texts read even when they are different.

1:1 TR (Δαβίδ) , M (Δαυίδ), WH (Δαυεὶδ), NU (Δαυὶδ)

So the name “David” is spelled three different ways, the 7 other words in this verse are exactly the same in all 5 Greek Texts.

1:5 TR (Βοὸζ), M (Βοὸζ), WH (Βοὲς), NU (Βοὲς)

So the name “Boaz” is spelled 2 different ways (2 times per verse 5).

1:5 TR (Ὠβὴ), M (Ὠβὴ), WH (Ἰωβὴδ), NU (Ἰωβὴδ)

So the name Obed is spelled two different ways (2 times per verse 5). The17 remaining words are exactly the same.

1:6 TR (Δαβὶδ), M (Δαυὶδ), WH (Δαυεὶδ), NU (Δαυὶδ)

So the name David is spelled three different ways (2 times per verse 6).

1:6 TR (Σολομῶντα), M (Σολομῶνα), WH (Σολομῶνα), NU (Σολομῶνα)

So the name Solomon is spelled two different ways.

1:6 TR (ὁ βασιλεὺς), M (ὁ βασιλεὺς), WH (omit), NU (omit)

So here is the first real difference of chapter 1, “the king” is contained in the TR, M Texts but the WH and NU do not contain these two words. The earliest manuscripts do not contain these words. The remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:7 TR (Ἀσά), M (Ἀσά), WH (Ἀσάφ), NU (Ἀσάφ)

So the name “Asa” is spelled two different ways. The 14 remaining words are exactly the same.

Now I will overview:

1:8 Asa & Uzziah are spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:9 Uzziah and Ahaz are spelled differently; remaining 12 words are exactly the same.

1:10 Amos and Josiah are spelled differently; remaining 12 words are exactly the same.

1:11 Josiah are spelled differently, remaining 12 words are exactly the same.

1:13 Eliakim is spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:14 Achim is spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:15 Mathan is spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1: 17 David is spelled differently, remaining 27 words are exactly the same.

1:18 TR (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ), M (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ), WH ([Ἰησοῦ] Χριστοῦ), NU (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ)

So the WH text reads “[Jesus] Christ” like the other three texts do, but brackets the name [Jesus]. There is a 7th century manuscript that does not contain the name Jesus in this verse.

1:18 TR (γέννησις), M (γέννησις), WH (γένησις), NU (γένησις)

So there is one letter difference here between these two words. The TR & M read “birth” and the WH & NU read “birth, origin”. So these words are often translated the same.

1:18 TR (γὰρ), M (γὰρ), WH (omit), NU (omit)

So the TR & M text reads “for”, yet this is almost not translatable in this passage. The first manuscript that contains “for” is a sixth century manuscript. The remaining 25 words are exactly the same in all four Greek Texts.

1:19 TR (παραδειγματίσαι), M (παραδειγματίσαι) , WH (δειγματίσαι), NU (δειγματίσαι)

So these two words are very similar, but with the preposition (παρα) added to the front of the word in the TR & M texts. These two different Greek words are closely related, and are most often translated the same. The remaining 15 words are exactly the same.

1:20 David and Mary are spelled differently; the remaining 29 words are exactly the same.

1:22 TR (τοῦ Κυρίου), M (τοῦ Κυρίου), WH (Κυρίου), NU (Κυρίου)

So the TR & M text has the definite article “the” before the word “Lord”, and reads “the Lord”. The WH and NU does not have the definite article “the” before the word “Lord”, yet because it is still definite, it is still translated “the Lord”. The remaining 14 words are exactly the same.

1:24 TR (διεγερθεὶ), M (διεγερθεὶ), WH (ἐγερθεὶς), NU (ἐγερθεὶς)

So the two different Greek words are almost the same, the preposition (δια) is added to (ἐγερθεὶς) in the TR & M texts, but both words are most often translated the same. The remaining 18 words are exactly the same.

1:25 TR (τὸν υἱὸν αὐτῆς τὸν πρωτότοκον), M (τὸν υἱὸν αὐτῆς τὸν πρωτότοκον) , WH (υἱὸν), NU (υἱὸν); Here the TR & M text reads, “her firstborn son” where WH & NU simply reads “a son”. The earliest manuscripts read “a son”. The remaining 14 words are exactly the same.

So when we are done looking at one chapter, comparing five different Greek texts, we have about 27 variants. Of these 27 most all are spelling differences and untranslatable. Two have some translatable differences, “the king” v.6, and “her first born” v.25; both seem to be additions that came into the text after the 4th century. Do you remember back earlier in this article when you were asked to choose between what group of manuscripts to base a Greek Text, A, W, M, WH, or TR? You might have thought then that there were going to be many serious differences. Surprisingly, of the translatable differences, we have 5 words. Two of these words, “the king” refer to David (v.6). What difference is there if David is called “the king” once (WH, NU) or twice (TR, M) in this same verse? The next three words, “her first born”(TR, M), but absent in (WH, NU). In this chapter she is called a “virgin” (v.23), and that, “before they came together she was found to be with child by the Holy Spirit” (v.18). By necessary conclusion then, Jesus would be understood as “her firstborn son” whether it is stated or not.

Now if a person is against the Bible and wants to criticize it, he could say that, “there are over 27,000 variants in Matthew chapter 1 alone! By taking 1000 manuscripts x 27 variants = 27,000. This looks extremely disheartening to someone who has not taken the time to look into them as we have here. When you begin to look carefully, there are only two that have any kind of real meaning at all, but these two are minimal.

Numbers can sometimes lie, per politicians, Bible critics, and those who would, “twist to their own destruction, as they do the other Scriptures” (2Peter 3:16). Jesus said, “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (John 8:32). Truth has nothing to fear by investigation. Let us go where the evidence leads. Paul said, “Test everything; hold fast what is good” (1Thess. 5:21), and I think we should apply this to manuscripts as well. To those who are honestly skeptical of the variants of the NT, I say the same thing Philip said to Nathaniel, “Come and See”. Come and take a look at the evidence. The honest skeptic, like Nathaniel was, after shown more evidence, should say, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” (John 1:49), like the thousands of manuscripts say to this day. Our New Testament Greek text is on solid foundation worthy to be trusted. If we do not trust the NT because of a few variants then we cannot trust any historical writings at all. No other historical writing comes close to the solid foundation of the New Testament.

In conclusion, I want to say that each Christian is like a handwritten manuscript, being read by the world around us, for good and bad. Some have pages missing because of neglect. Some have merely poor spelling; some have pages rewritten according to their own way of thinking. To the Corinthians Paul said, “And you show that you are a letter from Christ delivered by us, written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts” (2Cor. 3:3). The Christians at Corinth, with all their flaws, were still, “a letter from Christ”. Let us therefore make it our aim to represent the Original as best we can, and to his glory. Amen.

Reference works cited

Chart 1; has been produced by counting manuscripts from, Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT, 2nd ed. 1981, [pp.140-142 (9th-15th Byz. mss counted,159-162 (2nd - 9th counted); Daniel B. Wallace, Studies & Documents, THE TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT IN CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH, (chart 19.1 p.311) 1995; Philip Comfort, ENCOUNTERING THE MANUSCRIPTS, (pp.59-77, 267-270) as his papyri list is more up to date. This chart represents about 1000 manuscripts that have been identified under certain text-types; many manuscripts do not fit into a text type. Although a chart like this can never be 100% accurate, it does simplify a large amount of information. Some of the early papyri are counted as a manuscript, but some of them are just a few verses; I would agree that this is a little flawed. For charts per individual NT books, see, Philip Wesley Comfort, The Quest for the Original Text of the New Testament, chapter 8, 1992.)

Christopher De Hamel PhD., THE BOOK. A History of The Bible, p. 220, 2001; Senior Scholar, Medieval Texts, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Clarke, Kent D; Textual Optimism, 1997, pp.35-36 & p. 98

Combs, William W; Th.D, ERASMUS AND THE TEXTUS RECEPTUS; DBSJ 1 (Spring 1996): 35–53, )

Comfort, Philip W.; New Testament Text and Translation Commentary, p. xxvii, 2008. (also Michael D. Marlowe; http://www.bible-researcher.com)

Comfort, Philip; Encountering the Manuscripts, 2005, p.100

Lewis, Jack P; The English Bible From KJV to NIV, 1982, p42.

Metzger, Bruce M. & Ehrman, Bart D., The Text of the New Testament, 4th ed., 2005, p.152, 150, 174-5

Steven Kreis

UBS4

edition, introduction, p. 2 & p.3 Wallace,

Daniel B; Studies & Documents, THE TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT IN CONTEMPORARY

RESEARCH, p.313) 1995

By Dan Peters

From Expository Files 20.10; October 2013