The

English Translators: Their Work and Goals

The Integrity of the New Testament - Special 2013 Series

[From The Editors: This article is one of a series we are running this year.

The 2013 series is called "The Integrity of the

New Testament" and deals with textual criticism. Can the New Testament be

trusted? Has it been corrupted through time? Can we know what God has said? It

should be obvious how important this topic is. This is especially so given the

climate of society today and its attitudes toward the Bible. We wish this

series to help everyone understand the process of the Bible's history as a

document and why we can have confidence in its message. Near the end of the year

we are planning to publish these twelve articles in book form (Kindle, Nook and

old fashioned print and ink).

If not for the work of English translators, very few of us would have personal access to the written Word of God. We are very dependent upon the work of scholars far removed from us in time and circumstance. Without translation, most of us would be completely reliant upon a few with this "special knowledge" to know the meaning of a text in an ancient language. How great a loss we would experience! And yet for most of the centuries that stand between us and the Cross, Christians did not have access to the Scriptures in a form that they could read and understand.

Did William Tyndale indeed have a noble aspiration when he announced to a learned churchman, "If God spare my lyfe ere many years, I wyl cause a boye that dryveth ye plough, shall knowe more of the scripture than thou doest"? (Bible Translation: Why, What, and How?, Donald W. Burdick, Volume XXI -- Number 1, March, 1975, pp. 1-16, The Cincinnati Bible College & Seminary, http://www.dabar.org/semreview/bibtrans.htm). The Oxford scholar and monk Erasmus had previously said, “I would to God the plowman would sing a text of the Scripture at his plow, and the weaver at his loom would drive awey the tediousness of time. I would that the way faring man with this pastime wouldd expel the weariness of his journey.” (How We Got The Bible, Neil R. Lightfoot, p. 66, Sweet Publishing Austin TX, 1962)

The Preface to the King James Version addressed this very problem, and it formed the great impetus behind the work of the first English translators before them: “But how shall men meditate in that, which they cannot understand? How shall they understand that which is kept close in an unknown tongue? as it is written, Except I know the power of the voice, I shall be to him that speaketh, a Barbarian, and he that speaketh, shall be a Barbarian to me. [1 Cor 14] The Apostle excepteth no tongue; not Hebrew the ancientest, not Greek the most copious, not Latin the finest… Translation it is that openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most Holy place; that removeth the cover of the well, that we may come by the water, even as Jacob rolled away the stone from the mouth of the well, by which means the flocks of Laban were watered [Gen 29:10]. Indeed without translation into the vulgar tongue, the unlearned are but like children at Jacob's well (which was deep) [John 4:11] without a bucket or something to draw with; or as that person mentioned by Isaiah, to whom when a sealed book was delivered, with this motion, Read this, I pray thee, he was fain to make this answer, I cannot, for it is sealed. [Isa 29:11]” (Michael D. Marlowe, http://www.bible-researcher.com/kjvpref.html).

It is, of course, true that those who do not understand the Bible’s original languages are still dependent to a large degree upon the translators who do know them. This is a different and less severe problem, though, than having no translation to read at all.

Is Translation Permissible?

Are translations of Biblical texts proper? Did God intend the common man to understand His Word directly, or did He intend for His Word to be come to the people only through special teachers who had the ability to read the original language directly? The Catholic Church has taught even to modern times, that the Word is to be received from a person, and not through reading, and of course they opposed the work of the English translators with force and violence. This fact is the backdrop for understanding the early history of the English translators and their work.

To deny that translating the original language of the written Word is a proper activity involves several difficulties. First, it would mean that only those who understand the original language could ever understand a text, because it would logically prohibit a teacher from "explaining" a text to one who did not understand the original language - he would have to "translate" it. This would apply whether he wrote down his translation or not.

The second reason that translation out of the original language into the common tongue seems proper is the existence and use of the Septuagint (LXX). Consider this compelling information from the introduction to an 1810 edition of the King James Version. This edition is called the “Potters Standard Edition,” and says:

"The most remarkable translation of the Old Testament into Greek is called the Septuagint, which, if the opinion of some eminent writers is to be credited, was made in the reign of Ptolemy Philadelphus, about 270 years before the Christian era. At any rate, it is undoubtedly the most ancient that is now extant. …The transcendent value of this version may be seen from the extensive usage that it had attained in Jewish synagogues, from the fact that our blessed Lord and the apostles habitually quoted from it, and also from the fact that it helped to determine the state of the Hebrew text at the time when the version was made. Besides, it establishes, beyond all doubt, the point that our Lord and his inspired apostles recognized the duty of rendering the Word into the vulgar tongue of all people so that all men might, in their own speech, hear the wonderful things of the Lord. All the authors of the New Testament appear to have written in the Greek language. That this tongue was already familiar to them as a vehicle to express God's inspired Word is evident from their frequent use of the Greek translation, the Septuagint, in quoting the Old Testament and from the remarkable accordance of their style with the style of that ancient and precious version.” (http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/septuagint.html, http://books.google.com/books?id=VQBQAAAAYAAJ},

year={1855}, publisher={J.B. Perry}).

Also, the fact that the LXX is quoted so freely in the New Testament seems prima facie evidence that translations are approved. The original King James translators understood that the existence of the LXX translation and its use by the Lord undergirded their guiding principle – that the Word should be available in the common tongue to everyone.

A Brief History Of English Translations

Partial translations of the Bible into languages of the English people can be traced back to the end of the 7th century, including translations into Old English and Middle English. (English translations of the Bible, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_translations_of_the_Bible). And yet, for a thousand years during the Middle Ages, the Latin Vulgate was essentially the only translation of the Bible in Europe. This made the Word completely inaccessible to the masses. Of course, this situation was exactly as the Roman Catholic Church desired it to be - indeed they actively worked to preserve this circumstance.

An Oxford scholar, John Wycliffe, often called the “Morning-Star of the Reformation,” sought to change this situation beginning in the 1380s. He opposed various Catholic teachings, and his remedy was to translate the Latin Vulgate into English. He taught, and gathered disciples around the idea that the Word was authoritative, not Roman Catholic bishops. This became a foundational principle of the Reformation, but also became the basis for nearly all of the English translations. If the Word was authoritative then the people needed to be able to read it, rather than to simply rely upon the instructions of bishops and priests.

An interesting side note to Wycliffe’s translation was made by George Marsh:

“One of the most important effects produced by the Wycliffite versions on the English language is, as I have intimated, the establishment of what is called the sacred or religious dialect, which was first fixed in those versions, and has, with little variation, continued to be the language of devotion and of scriptural translation to the present day.” (George Marsh, The Origin and History of the English Language: and of the Early Literature it Embodies (New York: Charles Scribner, 1862):p. 365)

After Wycliffe’s execution, John Hus continued his work under the principle of the necessity of the people to read the Word for themselves. He too was burned at the stake, with Wycliffe’s Bibles as the kindling fuel. His last words were “In 100 years, God will raise up a man whose calls for reform cannot be suppressed.”

Another early translator, Thomas Linacre, compared the Vulgate to the Greek and said “[e]ither this (the original Greek) is not the Gospel… or we are not Christians.” Erasmus was also moved to correct the corrupted Vulgate, and used his collection of Greek manuscripts to publish a Parallel New Testament in 1516. It was the first New Testament to be printed on a printing press. His work on the Greek manuscripts later became known as the Textus Receptus. (Bruce M.Metzger, Bert D. Ehrman; The Text Of The New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 152).

William Tyndale used the Erasmus text to translate and publish the first edition of the Scriptures in English in 1525-26. Lightfoot called Tyndale “the true father of the English Bible.” (How We Got The Bible, Neil R. Lightfoot, p. 65; Sweet Publishing, Austin TX. 1962). Tyndale’s determination to bring the Scriptures to English-speaking peoples cost him his life in 1536, but the tide had turned against the suppression of translation. Soon, in 1536, Miles Coverdale published the first complete Bible in English, and soon after that John Rogers (Thomas Matthew) published the Tyndale-Matthew Bible, the first Bible in English that was translated from the original languages.

The Great Bible, or Cranmer’s Bible, followed in 1539, and was the first English Bible authorized and printed for public reading in churches. in 1560, the Geneva Bible was published in English by Coverdale and Foxe with the assistance of John Calvin. It was noted for four things: the “Breeches” that Adam and Eve wore, the first use of numbered verses which made notation and study easier, the strongly anti-Catholic Church marginal notes, and it was the first Bible taken to America.

The marginal notes of the Geneva Bible were also perceived as a threat by the Church Of England, so the Bishop’s Bible, a revision of the Great Bible was commissioned. It was never as popular as hoped, but became known as the “rough draft of the King James Version.” (How Did We Get the Bible?, Tracy M. Sumner, 2009, Barbour Publishing).

In 1582, the Catholic Church abandoned its stance that the Scripture should be in Latin only, and published their official version of the New Testament based on the Vulgate. Together with its Old Testament companion in 1609, it is known as the Douay-Rheims version.

The English Protestant clergy in 1604 made a push for a new translation to replace the Bishop’s Bible, and to supplant the Geneva Bible in the hearts of the people. They disliked it because of the marginal notes, and wanted notes only for clarification and cross-references. The King James Version was released in 1611 and became the most printed book in the history of the world. All King James Versions printed today are of the 1769 Baskerville revision.

The English Revised Version (1881), was the first “replacement” for the King James, and the first English Bible not to contain the Apocrypha. The American Committee agreed not to publish their revisions for twenty years, and so the American Standard Version was released in 1901. It contains in an appendix the notes from the English Committee, and is considered a very literal translation, as is its more modern revision, the New American Standard Bible (1971).

The literal nature of the American Standard and New American Standard were viewed as literary faults by some, and so a “dynamic equivalent” in modern English was published as the New International Version in 1972. It uses “phrase-for-phrase equivalency rather than word-for-word, and was designed to be easier to read.

The New King James Version (1982) is not significantly different than the King James Version, except that it modernizes archaic words and pronouns (“wist,” “Thee,” “Thou,” etc.). It follows the Textus Receptus, but does note major variants, such as the end of Mark, as being absent in the older texts.

In 2002, the English Standard Version was published. It is a literal translation that was designed to be simple and readable.

(http://www.greatsite.com/timeline-english-bible-history/; John L. Jeffcoat III)

A Definition of Translation

Of course, “translation” is simply the process of expressing the sense of words or text in another language than the original. But translation is not altogether simple. Most languages are full of idioms and colloquialisms that may not exist in exact form in the second language. And with the Bible, the factor of age and ancient, unknown cultures compound the problem. It appears that we have in some of our English translations we have not only facets of Biblical cultures reflected in the text, but also relics of 16th Century English culture (“Bishops, “Easter,” etc.). Are these insurmountable problems, or merely matters of teaching and seeking? Some will be satisfied with a cursory paraphrase, much like the majority would if they were curious about what Homer wrote. For the serious seeker of God, however, this is not adequate.

Francis Steele gives this definition of the word translate/translation, “A translation should convey as much of the original text in as few words as possible, yet preserve the original atmosphere and emphasis. The translator should strive for the nearest approximation in words, concepts, and cadence. He should scrupulously avoid adding words or ideas not demanded by the text. His job is not to expand or to explain, but to translate and preserve the spirit and force of the original... Not just ideas, but words are important; so also is the emphasis indicated by word order in the sentence.” (Francis R. Steele, Translation or Paraphrase, (St. Louis, MO: Bible Memory Association International, 1960), pp. 1-4).

“No translator can transcend his own time; he can only work in light of the knowledge of his day, with materials available to him, and put his translation in words spoken by his generation.” (Lightfoot, p. 72).

Types of translation

There are four basic theories or methods of translation which have been used in translating the Bible from the original languages.

1. Literal or Highly Literal. This is where the exact words, word order and syntax are as literally followed and translated into English as possible. Many of the interlinears, such as Berry's Interlinear are examples of this method of translation. Young's Literal Translation is another example of this method of translation.

Even though these are highly accurate to the Greek, they are difficult to read in English. For instance YLT reads in John 3:16, "for God did so love the world, that His Son - the only begotten - He gave, that every one who is believing in him may not perish, but may have life age-during." Berry's Interlinear reads, "For so loved God the world that his Son the only begotten he gave, that everyone who believes on him may not perish but have life eternal."

Although these are accurate translations, due to word order and syntax they are difficult to read in English. They are best used as tools for those who wish to study the literal English translation alongside the original language. And for those who are more concerned with the structure of the original than the structure of English. They would be difficult to use in public readings or even daily Bible reading. (Ted J. Thrasher, http://www.kc-cofc.org/Articles/Translations.htm).

2. Formal Equivalence, Form-Oriented or Modified Literal. This is where the actual words are translated and then adjusted slightly in order and syntax to conform to the target language. This method respects the verbal inspiration of the Scriptures. It focuses on the form or the very words of the text and translates them. It is based upon the philosophy that each and every word of the text is important and carries a meaning of its own which is possible to express in another language.

This method involves a single process whereby the words are directly translated from the original to the target language. The emphasis is given to translating the words and the various parts of speech as closely as is possible without distorting the meaning. This means that nouns are translated as nouns, verbs as verbs, articles as articles, adverbs as adverbs and adjectives as adjectives. Close attention is given to grammar so that tenses, moods, numbers and persons are translated as closely as possible. The KJV is especially accurate in translating the second person plural as "ye" (a distinction which is lost in many versions by translating both singular and plural numbers as "you").

This method is sometimes recognized (and criticized) as the word-for-word method of translation. It is the most accurate of all methods of translation in versions which are readily available. It is the method which was employed by the KJV, ASV and NKJV translators. Because of these translator's respect for each word, when they added English words which did not correspond to a Greek word, they italicized these words, so that the reader could know that these words were supplied by the translators. This type of honesty and ethical responsibility cannot be found in the modern-speech versions today.

There are three translations which generally assigned to the category of word-for-word translations which are currently available today. They are the KJV, the ASV and the NKJV.

The KJV translators, for example, were guided by 15 rules, among them were these:

“1. The ordinary Bible read in church, commonly called the Bishop's Bible, to be followed and as little altered as the truth of the original will permit.

4. When a word hath divers significations, that to be kept which hath been most commonly used by most of the ancient fathers.

6. No marginal notes at all to be affixed, but only for the explanation of the Hebrew or Greek words, which cannot without some circumlocution be so briefly and fitly expressed in the text.” (Gustavus S. Paine -- "The Men Behind the KJV" Baker Book House/1979).

The Preface to the New King James Version states: “Where new translation has been necessary in the New King James Version, the most complete representation of the original has been rendered by considering the history of usage and etymology of words in their contexts. This principle of complete equivalence seeks to preserve all of the information in the text, while presenting it in good literary form. Dynamic equivalence, a recent procedure in Bible translation, commonly results in paraphrasing where a more literal rendering is needed to reflect a specific and vital sense.” (Preface iii).

3. Functional Equivalence, Context-Oriented, Idiomatic or Dynamic Equivalence. This method of translation departs from the formal equivalence method in two areas: 1) It is concerned with the thought of the writer, and (2) The reaction of the translated message by the person reading it. It is based on the underlying theory that communication takes place, not in word form, but in sentence form or that the sentence is the smallest unit of communication.

The Dynamic Equivalence method of translation is defended by Eugene A. Nida and Charles R. Taber in The Theory and Practice of Translation. They write: “The new focus (Dynamic Equivalence)…has shifted from the form of the message to the response of the receptor. Therefore, what one must determine is the response of the receptor to the translated message. The response must then be compared with the way in which the original receptors presumably reacted to the message when it was given in its original setting.” (Nida, Eugene A., and Charles Russell Taber. The Theory and Practice of Translation: Fourth Impression. Vol. 8. Brill Academic Pub, 2003., p 1).

The obvious limitations of this are that we may be inaccurate in discerning the intent of the author or the reception by the reader.

One of the problems of translating any language is that idioms in one language do not always transfer over into another. For example, the Greek expression that a woman is pregnant is literally, “she is having it in the belly.” When the OT speaks of God’s anger, it says, “God’s nostrils are enlarged.”

Further, a major problem with formal equivalence, or literal translation, is that although it may work on a cognitive level, it often fails on an emotional level. The goal of a translator is not only to reproduce the message of the original, but also to reproduce the impact of that original message. This requires another approach.

Dynamic equivalence is more phrase-for-phrase translation, and It is more interpretive. (Wallace, ibid). Ironically, the desire for evangelism prompted translators in the 20th century to seek a method beyond the literal. They argued, (many out of their experience), that the non-Christian masses cannot understand the literally translated Word. The believed that more idiomatic translation would solve the problem, both for native English speakers, and especially those in South America or Africa whose languages are very unstructured. This is why the dynamic equivalence method was developed.

Eugene Nida asserted that “the real test of the translation is its intelligibility to the non-Christian.” (Eugene Nida, Bible Translating: An Analysis of Principles and Procedures, with Special Reference to Aboriginal Languages, New York: American Bible Society, 1947, p. 21). See also, Donald A. Carson, “New Bible Translations: An Assessment and Prospect,” in The Bible in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Howard Clark Kee (New York: American Bible Society, 1993), pp. 57-59.

Wallace provides another example of this from the New English Bible (1970).

1.1—Virtually all translations follow the KJV, which follows Tyndale: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

The NEB is very bold to depart from that tradition rendering here: “In the beginning the Word already was. The Word was in God’s presence, and what God was, the Word was.” Although this is not as literal as the traditional rendering, it is actually more faithful to the meaning of the original. John is not saying that the Word is the same person as God; he’s saying that he shares the same essence that God has. In the original Greek, this statement is the most concise way that John could both affirm that Christ is equal to the Father and distinct from the Father. The NEB captures that truth better than any other translation.”

The New International Version is an example of this method. The Preface notes that the translators, “have striven for more than a word-for-word translation. Because thought patterns and syntax differ from language to language, faithful communication of the meaning of the writers of the Bible demands frequents modifications in sentence structure and constant regard for contextual meaning of words.” Notice the emphasis is not upon the words of the writers of the Bible, but the thoughts or contextual meaning.

Today's English Version: TEV (Good News For Modern Man ) is sometimes placed in this category, even though is often considered a paraphrase. In the Preface it says, “As a distinctly new translation, it does not conform to traditional vocabulary or style, but seeks to express the meaning of the Greek text in words and forms accepted as standard by people everywhere who employ English as a means of communication. .[T]here has been no attempt to reproduce in English the parts of speech, sentence structure, word order and grammatical devices of the original language" (Preface of GNMM p iv).

An interesting defense of gender-inclusive translation is based on Dynamic Equivalence:

“Such translations (“dynamic equivalence” or “functional equivalence”) try to do something on the order of common sense: When arriving at a word or phrase that literally says one thing but functionally means another, they choose the functional meaning. In biblical times, speakers would address a mixed group of believers with the greeting "brothers." Such was the practice even in English a generation ago. If a speaker were to do that today, many people in the room would assume the speaker was addressing his remarks only to the men present. If we translate the Greek word adelphoi as "brothers" in many biblical passages, it would lead the modern reader to the same conclusion. In short, it would mislead the reader. Hence, the need for functional translations.” (Christianity Today, “Battle For Bible Translation, September 2011, http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2011/september/bible-translation-battles.html).

4) Paraphrase Method. No serious attempt is made to follow the form or grammar of the original. The focus is on simply conveying the general thought. While there is certainly a place for commentary and paraphrase, it should not be called “translation” in the context of the Word Of God. Examples of this method include The Living Bible, The Message, Today’s English Version (Good News Bible), Goodspeed, Philips. While the paraphrase Bible has a place in some situations, especially versions like Goodspeed or Philips, they should not be confused with an actual translation.

Most popular Bible translations fall somewhere along the spectrum of formal equivalency and dynamic equivalency. No translation is an exact word-for-word, literal translation. Towards the formal-equivalency end are the American Standard, the New American Standard Bible (generally considered the most literal English translation), the King James and New King James Versions. From the dynamic-equivalency method we get the New International Version and the New Living Translation.

Both forms of translations have their strengths and their weaknesses. And many people will utilize one form for a certain type of use (e.g., the dynamic equivalency format for general reading) and the other for a different purpose (e.g., a formal equivalency for word studies). (The Blue Letter Bible And Translation, http://www.blueletterbible.org/help/why_kjv.cfm).

For an interesting chart that classifies many translations by the predominant method used in translating, please refer to the Wikipedia entry for “Dynamic And Formal Equivalence.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_and_formal_equivalence).

In the next section, consider some specific goals of translation for the major English translations available to us today.

Translation goals of King James Version

The goal of the King James translators “was not to make a new translation but to revise the 1602 edition of the Bishop’s Bible.” (Lightfoot, p. 68) As much as 80% of the work is re-used from Tyndale’s translation. The did compare that translation to the original languages, and revise it as necessary. The fact this work was done by a large committee (48-54) seems to have given it an impartiality that served to give it longevity. They said in the Preface, "Truly, we never thought, from the beginning... that we should need to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one; but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one." (“The Genesis of the King James Bible”, http://www.kingjamesbibletrust.org/the-king-james-bible/kjv-timeline/genesis).

“These tongues therefore, the Scriptures we say in those tongues, we set before us to translate, being the tongues wherein God was pleased to speak to his Church by his Prophets and Apostles.”

“Another thing we think good to admonish thee of (gentle Reader) that we have not tied ourselves to an uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe, that some learned men somewhere, have been as exact as they could that way. Truly, that we might not vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere) we were especially careful, and made a conscience, according to our duty. But, that we should express the same notion in the same particular word; as for example, if we translate the Hebrew or Greek word once by Purpose, never to call it Intent; if one where Journeying, never Traveling; if one where Think, never Suppose; if one where Pain, never Ache; if one where Joy, never Gladness, etc.”

“Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old Ecclesiastical words, and betake them to other, as when they put Washing for Baptism, and Congregation instead of Church: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their Azimes, Tunike, Rational, Holocausts, Praepuce, Pasche, and a number of such like, whereof their late Translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof, it may be kept from being understood. But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.” (Preface To The King James Version, http://www.bible-researcher.com/kjvpref.html).

Michael D. Marlowe noted this about form and translation goals of the the King James Version in general: “It was generally superior to the Geneva Bible in literal exactness. Verses were numbered, each one being made a separate paragraph now for ease of reference. A different type was used for supplied words, as in the Geneva Bible.” King James himself seems to have laid down the guideline that there should be no notes of any kind except what was necessary to translating the text. (Lightfoot, p. 68). This proved to be very wise, and paved the way for the eventual overwhelming popularity of the new translation.

Three weaknesses of the King James Bible led to the desire for newer versions. (Lightfoot, p. 72-73). First, the KJV rests upon an inadequate textual base, according to most scholars. This is especially try of the New Testament. The KJV translators simply did not have at their disposal many manuscripts which are now known – the Vatican, the Sinaitic, the Alexandrian, and the Ephraem manuscripts. Secondly, the King James, after 400 years, contains many archaic words whose meanings obscure or mislead- such as “allege” for “prove,” “communicate” for “share,” “suffer” for “allow,” “allow” for “approve,” let” for “hinder,” “prevent” for “precede,” “conversation” for “conduct” etc. These usages can be misleading, not just cumbersome. Third, The KJV contains several errors in translation, reflection the state of knowledge of Hebrew and Greek of that era.

Translation goals of Revised Version/American Standard Version

in 1870 two committees of about 27 scholars each were formed to begin the Revised Standard Version. They included such men as B.F. Wescott, F.J. A. Hort, J. B. Lightfoot, R.C. Trench, A. B. Davidson, Philip Schaff, J. H. Thayer and William Henry Green. Their work was released in 1881 (NT), and 1885 (OT). (Lightfoot, p. 73)

From the title page: “The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments, Translated out of the Original Tongues, Being the Version Set Forth A.D. 1611, Compared with the Most Ancient Authorities and Revised A.D. 1881-1885, Newly Edited by the American Revision Committee A.D. 1901, Standard Edition. New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1901.”

"English Versions" by Sir Frederic G. Kenyon in the Dictionary of the Bible edited by James Hastings, and published by Charles Scribner's Sons of New York in 1909 (http://www.bible-researcher.com/erv1.html)

“The article TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT describes the process of accumulation of materials which began with the coming of the Codex Alexandrinus to London in 1625, and continues to the present day, and the critical use made of these materials in the 19th century; and the story need not be repeated here. It was not until the progress of criticism had revealed the defective state of the received Greek text of the New Testament that any movement arose for the revision of the Authorized Version. About the year 1855 the question began to be mooted in magazine articles and motions in Convocation, and by way of bringing it to a head a small group of scholars.”

“Meanwhile a great stimulus to the interest in textual criticism had been given by the discovery of the Codex Sinaiticus, and by the work of Tischendorf and Tregelles. In February 1870 a motion for a committee to consider the desirableness of a revision was adopted by both houses of the Convocation of Canterbury; and definite motions in favor of such a revision were passed in the following May. The Convocation of York did not concur, and thenceforth the Southern Houses proceeded alone. A committee of both houses drew up the lists of revisers, and framed the rules for their guidance. The Old Testament company consisted of 25 (afterwards 27) members, the New Testament of 26. The rules prescribed the introduction of as few alterations in the Authorized Version as possible consistently with faithfulness; the text to be adopted for which the evidence is decidedly preponderating, and when it differs from that from which the Authorized Version was made, the alteration to be indicated in the margin (this rule was found impracticable); alterations to be made on the first revision by simple majorities, but to be retained only if passed by a two-thirds majority on the second revision.”

The Revision Committees relied heavily upon the Masoretic text for their Old Testament translation. The changes here generally slight, most noticeable in the prophetical and poetic books, according to Kenyon.

But, “The New Testament revisers had, in effect, to form a new Greek text before they could proceed to translate it. In this part of their work they were largely influenced by the presence of Drs. Westcott and Hort, who, as will be shown elsewhere [TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT], were keen and convinced champions of the class of text of which the best representative is the Codex Vaticanus.”

“To Westcott and Hort may be assigned a large part of the credit for leading the Revisers definitely along the path of critical science; but the Revisers did not follow their leaders the whole way, and their text (edited by Archdeacon Palmer for the Oxford Press in 1881) represents a more conservative attitude than that of the two Cambridge scholars.”

“Nevertheless the amount of textual change was considerable, and to this was added a very large amount of verbal change, sometimes (especially in the Epistles) to secure greater intelligibility, but oftener (and this is more noticeable in the Gospels) to secure uniformity in the translation of Greek words which the Authorized Version deliberately rendered differently in different places (even in parallel narratives of the same event), and precision in the representation of moods and tenses. It was to the great number of changes of this kind, which by themselves appeared needless and pedantic, that most of the criticism bestowed upon the Revised Version was due; but it must be remembered that where the words and phrases of a book are often strained to the uttermost in popular application, it is of great importance that those words and phrases should be as accurately rendered as possible. On the whole, it is certain that the Revised Version marks a great advance on the Authorized Version in respect of accuracy, and the main criticisms to which it is justly open are that the principles of classical Greek were applied too rigidly to Greek which is not classical, and that the Revisers, in their careful attention to the Greek, were less happily inspired than their predecessors with the genius of the English language.”

The American Committee also made a noticeable change from previous English versions by substituting “Jehovah” for Lord” and “God” whenever the word YHWH appeared in the text. (see their Preface). They also more uniformly translated the word “Sheol” in the text, finding no reason for its inconsistent use in the older versions.

The ASV translators closed their Preface with this statement: “The present volume, it is believed, will on the one hand bring a plain reader more closely into contact with the exact thought of the sacred writers than any version now current in Christendom, and on the other hand prove itself especially serviceable to students of the Word.” They sought to be simple enough to be understood by all, and yet literal enough to be useful to scholars.

Lightfoot gives this evaluation of the American Standard Version of 1901: 1) It is based on a Greek text which is far superior to that used by the King James translators; 2) the revisers rendered the text more accurately; and 3) the revisers cleared up misleading archaisms of the King James. Yet, what it gained in accuracy and consistency, many think that it lost in naturalness and beauty. Charles Spurgeon expressed what many think – “strong in Greek, weak in English.”

The Translation goals of the Revised Standard Version

“Nearly fifty years passed before the next major translation was done. The impoverished style of the ASV prompted the International Council of Religious Education to recommend a revision. The work began in 1937 and the committee of 32 scholars consciously tried to make the RSV preserve the qualities of the KJV that had made it so great.” (Daniel Wallace, The History Of The English Bible Part IV: Why So Many Versions?, https://bible.org/seriespage/part-iv-why-so-many-versions).

Although it sold well at first, and received praise from scholars such as F.F. Bruce, not everyone took a liking to the RSV. It is in fact the most hated English translation of all time. (Wallace, ibid). In fact Wallace says that the explosion of new translations in English in the last half of the 20th Century was a section, a negative reaction, to the RSV. It was perceived as a biased translation by conservatives because it had been sponsored by the National Council Of Churches, and they had to look no farther than Isaiah 7:14, and the translation of “alma” as “young woman” instead of “virgin” to find a popular rallying point.

Translation goals of New American Standard Bible

From the Preface of the New American Standard Bible (1971): “The editorial Board had a two-fold purpose in making this translation to adhere as closely as possible to the original language of the Holy Scriptures. To make the translation in a fluent and readable style according to current English usage. (This translation follows the principles used in the American Standard Version 1901 known as the Rock of Biblical Honesty.)” The translators expressed a “four-fold aim: 1) These publications shall be true to the original Hebrew and Greek. 2) They shall be grammatically correct. 3) They shall be understandable to the masses. 4) They shall give the Lord Jesus Christ his proper place, the place which the Word gives Him; no work shall ever be personalized.”

Among the Principles of Revision which they followed are the use of the latest Greek manuscripts. The 23rd edition of the Nestle text was followed in most cases. They attempted to render any outdated grammar and terminology of the ASV into more modern usage. When they chose to modify the literalness of the ASV for the sake of readability, they noted the literal reading in the margin. In the Old Testament, Rudolph Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica was used.

Translation goals of New International Version

The New International Version stands as a counterpoint to the literalness of the ASV/NASB. It is a dynamic equivalent “phrase-for-phrase translation, not formal equivalent “word-for-word.” It was meant to be readable at a Junior High School level and appeal to a broader, less-educated audience. Critics have for this reason jokingly referred to it as the “Nearly Inspired Version.”

It was not based on any previous version but was an entirely new translation in idiomatic 20th Century English. The New Testament translators, all subscribers to Evangelical statements of faith, took as their starting point the first and second editions of the Greek New Testament published by the United Bible Societies (see Aland Black Metzger Wikren 1966), but did not follow the UBS text in all places. Recently a Greek text which purports to give the readings adopted by the NIV committee has been published under the title A Reader’s Greek New Testament (Zondervan, 2004). See also: http://biblica.com/niv/.

One principle that guided the NIV translators was their objection to the way that the RSV had translated the Old Testament without regard for the New Testament usages of these passages. They stated that “the translation shall reflect clearly the unity and harmony of the Spirit-inspired writings.” (Stephen W. Paine, “Twentieth Century Evangelicals Look At Bible Translation,” Wesleyan Theological Journal 4/1 (Spring, 1969), p. 86.) This is shown in the past verb used in Genesis 2:19 to harmonize with Genesis 1, and the translation of “alma” in Isaiah 7:14 as “virgin,” and not “young woman” as in the RSV.

The NIV the Committee adopted the following nine guidelines:

(1) At every point the translation shall be faithful to the Word of God as represented by the most accurate text of the original languages of Scripture.

(2) The work shall not be a revision of another version but a fresh translation from the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

(3) The translation shall reflect clearly the unity and harmony of the Spirit-inspired writings.

(4) The aim shall be to make the translation represent as clearly as possible only what the original says, and not to inject additional elements by unwarranted paraphrasing.

(5) The translation shall be designed to communicate the truth of God’s revelation as effectively as possible to English readers in the language of the people. In this respect, the Committee’s goal is that of doing for our own time that which the King James Version did for its day.

(6) Every effort shall be made to achieve good English style.

(7) The finished product shall be suitable for use in public worship, in the study of the Word, and in devotional reading.

(8) The project shall be a representative cooperative endeavor so that the finest scholarship may be applied, so that the version may be as free as possible from the individual theological biases of the translators, so that constructive criticism from many and varied quarters may be brought to bear on the work in its formative stages, and so that the churches may be prepared adequately to receive and use the new translation when it becomes available.

Those engaged in the work of translation shall not only possess the necessary requirements of scholarship, but they shall also look upon their labor as a sacred trust, honoring the Bible as the inspired Word of God. (Stephen W. Paine, “Twentieth Century Evangelicals Look At Bible Translation,” Wesleyan Theological Journal 4/1 (Spring, 1969), p. 86).

(9)

The New International Version has been criticized for poor translations that show a Protestant bias, (by N.T. Wright, no less), as well as by Roman Catholics. It has been criticized by conservatives for many poor readings, and especially for its phrase-for-phrase translation method. Daniel Wallace of Dallas Theological Seminary observed, “Readability seems to have been a higher priority than anything else” in the making of the NIV. (Daniel Wallace, The History Of The English Bible Part IV: Why So Many Versions?, https://bible.org/seriespage/part-iv-why-so-many-versions).

.

Related to this is the problem of the NIV not “sounding sacred.” “The idiomatic style seemed to make the sacred text less impressive and less memorable than most conservatives would prefer. As Professor Wallace said, “It is so readable that it has no memorable expressions, nothing that lingers in the mind. This is a serious problem for the NIV that is not always acknowledged.” (Daniel Wallace, The History Of The English Bible Part IV: Why So Many Versions?, https://bible.org/seriespage/part-iv-why-so-many-versions).

Translation Goals Of The New King James Version

The New King James Version is a conservative revision of the King James version that does not make any alterations on the basis of a revised Greek or Hebrew text, but adheres to the readings presumed to underlie the King James version. In the New Testament, this means that the Greek text followed is the Textus Receptus of the early printed editions of the sixteenth century. The ancient manuscripts, upon which critical editions of the Greek text have been based for nearly two centuries now, are ignored (except in the marginal notes).

The NKJV revisers followed the essentially literal method of translation used in the original King James Version, which the NKJV Preface calls “complete equivalence,” in contrast to the “dynamic equivalence” of less literal versions.

This statement from the Preface is worth noting:

“In faithfulness to God and to our readers, it was deemed appropriate that all participating scholars sign a statement affirming their belief in the verbal and plenary inspiration of Scripture, and in the inerrancy of the original autographs.” (Preface to the New King James Version, http://www.bible-researcher.com/nkjv.html#preface).

Newer Translations

New Revised Standard (NRSV) was one of the first “gender-inclusive” translations, exchanging “man” in many places with “anyone,” for example. In 1 Timothy 3:2, instead of saying that elders should be “the husband of one wife,” the NRSV says that the elder should be “married only once.”

The translators of the NRSV defend their gender-inclusive policy in this way: ”Its groundbreaking use of nonsexist language for generic pronouns—for example, “brothers and sisters” instead of “brothers”—corrects a long-standing problem with English translations of the Bible. Because of a lack of a generic third person singular pronoun, previous translations used “he” or “him” when both men and women were indicated, often obscuring the original meaning.” (http://www.nrsv.net/about/about-nrsv/) So, in their view, it is truer to the original meaning.

Gender-inclusive translations are objectionable to those who believe in the verbal inspiration of true original texts.

The English Standard Version (ESV) was published in 2002, and was an attempt to bridge the gap between the readability of the NIV and the literal accuracy of the NASB. It is a revision of the 1971 edition of the Revised Standard Version. The translators' stated purpose was to follow an "essentially literal" translation philosophy while taking into account differences of grammar, syntax and idiom between current literary English and the original languages. (Decker, Rodney (2004), “The English Standard Version: A Review Article”, The Journal of Ministry & Theology 8 (2): 5–31).

Some have objected to the ESV because it does not translate “anthropos” as “man/men.” (Some of these changes are explained in the marginal notes, as for “adelphoi” in Romans 1:13.) But generally it is viewed as very accurate and literal. Some have praised it for its “corrections” of the RSV translations involving several Old Testament prophecies, such as Genesis 22:15-18, Psalm 2:11-12, Psalm 16:10, and Isaiah 7:14. (Marlowe, http://www.bible-researcher.com/esv.html).

English translation will continue to be published. Modern mans restlessness may be the driving force behind the proliferation of versions in the last 100 years, but much of this can simply be attributed to the deficiencies of existing translations. When reverent care is exercised perhaps good can be done. All should consider, though, the problem that George Marsh addresses:

“A new translation of the Bible, therefore, or an essential modification of the existing version, is substantially a new book, a new Bible, another revelation; and the authors of such an enterprise are assuming no less a responsibility than that of disturbing, not the formulas only, but the faith of centuries. Nothing but a solemn conviction of the absolute necessity of such a measure can justify a step involving consequences so serious, and there are but two grounds on which the attempt to change what millions regard as the very Words of Life, can be defended These grounds, of course, are, first, the incorrectness of the received version, and secondly, such a change in the language of ordinary life, as removes it so far from the dialect of that version, that it is no longer intelligible without an amount of special philological [p. 639] study out of the reach of the masses who participate in the universal instruction of the age.” (George P. Marsh, Lectures On The English Language, Lecture XXVIII, “The English Bible,” 4th ed., New York: Charles Scribner, 1861, pp. 617-43.)

It is very problematic for true conservatives to recommend some “translations” for any purpose – such as The Message, and other paraphrases. Those who care what God says will really want to read what God says, not an unserious or even irreverent paraphrase.

And yet, there is no perfect translation. Many have gives the advice as expressed by Daniel Wallace:

“And this is why there is no simple answer to the question, ‘What’s the best translation available today?’ No translation can capture the full force of the original. The best we can do is to own several different kinds of translations. You may need one for serious study, another for casual reading, and another for memorizing. But don’t shortchange yourself by thinking that one Bible is all you need. The only Bible that can make that claim is the Greek and Hebrew Bible.” (Daniel Wallace, The History Of The English Bible, Part IV: Why So Many Versions?, https://bible.org/seriespage/part-iv-why-so-many-versions).

Conclusion

Modern speakers of English are deeply indebted to the English translators of the Bible. Many paid with their own blood for this work. They did so because of a commitment that the Word was authoritative, life-giving, and that every man had the right to read it for himself. As decades and centuries go by, and the language changes, may God raise up men who will have this same dedication to faithfully render the inspired Word for men to read, that the seed may be planted in new hearts.

The average person in Jesus’ day knew how to “put new wine into fresh wineskins, and both are preserved" (Mat 9:17). To preserve most things is relatively easy, even for man. I have often thought about the fact that the books of the NT were written on perishable papyri. Papyrus is basically a tall grass. Even though, “the grass withers, the flower fades”, yet, “the word of our God stands forever” (Isa 40:8). How ironic that God’s word was placed upon grass (papyri) and the grass withered, but the words written on it did not. Why not? Because each generation that followed, put new ink into fresh writing material and much was preserved, actually too much material for the common man. Today there are over 5800 Greek manuscripts or fragments of manuscripts to read, to date, to categorize, and finally to put in some sort of family tree. There are about twice as many Latin manuscripts as there are Greek.

It would take about 150 animal hides and seven miles of text put end to end to produce one Latin Bible. Goderannus, a scribe, did this for the second time in his life in 1097AD. He put in a note in this manuscript that it took himself and a colleague four years to make this one manuscript (De Hammel, 2001). These Bibles were almost exclusively used in monasteries and church buildings. It is about 1140AD when the Bible could be commonly purchased (ibid. p.87). Men from the first century have dedicated themselves in preserving the great treasure of the scriptures in their own language. I thank God for these men, and those who followed.

Which manuscripts should be used and compared on which to base a printed Greek text? With so many manuscripts, it is no wonder conscientious and truth seeking scholars do not always agree on which set manuscripts should take priority. Limited in scope, I will briefly deal below with the printed editions of Erasmus, the Textus Receptus, Westcott and Hort, the Majority text, and the Nestle Aland - United Bible Society editions. My main objective will be to let the general reader, who is not an expert in textual matters, get a sense on how to view these editions.

Prior to the invention of the printing press which took place in about 1450 AD, there were no editions of the Greek New Testament. If you happened to live in Western Europe and were fortunate enough to have access to a hand written Greek NT manuscript, it probably would be no more than a curious glance because, “the Bible” was the Latin Vulgate. It is worth pausing to consider that the language of the first printed Bible was in Latin, not Greek or English. The printed Vulgate Bible was being “... sold at the 1455 Frankfurt Book Fair, and cost the equivalent of three years' pay for the average clerk” (Kreis, 2012). Then, after sixty years of the Vulgate being produced in several different printings by different scholars, in 1516 AD Erasmus’ Latin text was also printed, and alongside of it, his Greek text of the NT.

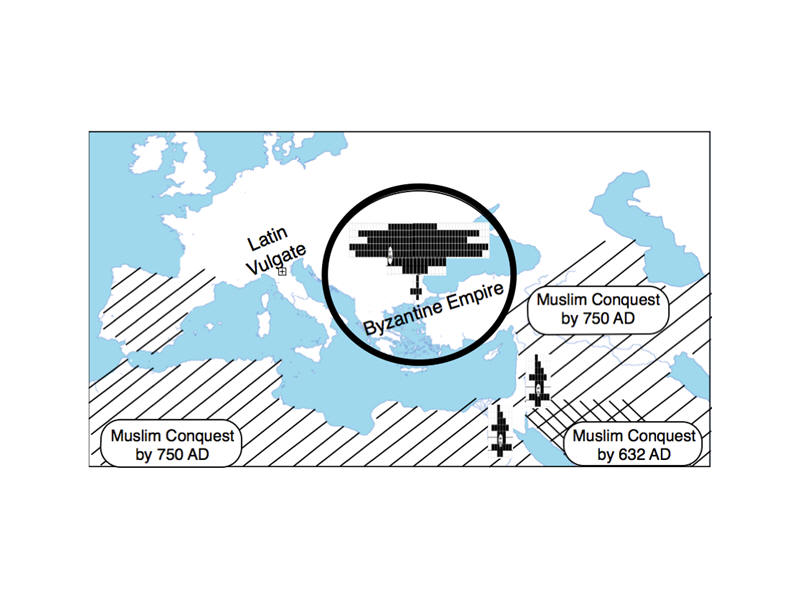

What eventually brought about a need to have a printed edition of the Greek New Testament? There are at least three factors that come into play. First of all, Greek scholars and Greek manuscripts had been fleeing from the Muslim conquest of Byzantium. “Constantinople fell to the Muslims in 1453... Greek-speaking refugees escaped some bringing books. For the first time, early Greek manuscripts became in quantity in the West” (De Hamel, 2001). Secondly there was an academic need that was growing stronger in Western Europe, i.e. the renaissance (1300 - 1700 AD). This need was not purely academic, but if one were to correct some of the erroneous readings imbedded in the Latin Vulgate, it would have to have a justifiable basis, so Erasmus turned to the underlying Greek text for his justification. Thirdly, the printers or those who sponsored a book had to see a market for their book before they would risk the high price of publication. The Greek New Testament fell short in this regard, for it was simply added on the opposing column, to “accompany and support” Erasmus’ own revision of the Latin Vulgate. Nevertheless, the Greek text finally came off the press, and to the public. The public forgot about his revision of the Vulgate and held onto his Greek printed text. We will pick up with Erasmus after we overview the Greek manuscript text types.

The chart below is a limited summary of the Greek manuscript tradition at a glance. I will be referring back to chart 1 in the paragraphs below so it is worth taking a moment to familiarize yourself with it. There are about 1000 manuscripts placed in this chart, most of them in the M group. For more information about the basis of this chart see the end note “chart 1”.

Based upon similar readings we have three groups or families of manuscripts. On the left we have the centuries listed, from the 1st century to the 15th. The A group of manuscripts is seen from the 2nd century to the 13th; the W group is from the 3rd to the 6th; and the M group is from the 5th to the 15th as charted.

A W M

Which group is more accurate?

Now

beginning with this next step scholars disagree, and a few of them very sharply.

Which manuscripts should be considered in comparing or collating for printing a

Greek text? “A” group goes back to the 2nd century, “W” group to the 3rd, and

“M” group to the 5th century. So as you look at the chart, what group of

manuscripts would you choose that most accurately reflects the original

writings? Would you choose group A, W, M, or a subset of A, the WH; or a

subset of M, the TR? Your answer? ___ Would you like more information before

choosing? Of course. Yet, in fact you have most likely already chosen without

realizing it. Our English versions are based upon different manuscripts and

different Greek Texts generally. If you are reading the King James Version or

the NKJV, you are reading a NT translation based on the TR, the Textus Receptus,

which was formed by comparing a handful of manuscripts in group M, see the much

smaller subset, “TR” located in chart 1. If you are reading the 1901 American

Standard Bible, you are reading a translation based upon a merger of at least

two previous Greek Texts, one of Westcott and Hort and secondly of Tregelles

(Comfort, 2008). This text would be located in group A. The Westcott and Hort

text is based predominately upon two fourth century manuscripts of high standing

of group A, along with other early manuscripts. If you are reading the New

Testament in NASB, NIV, or the ESV you are reading a translation based upon

manuscripts that are found in group “A” for the most part. Now let me assume

that you have spent time in a Bible class where these different translations

have been used. If so, you realize already the general differences that are

displayed in these two groups of manuscripts (group A & the smaller subset TR)

are not so different that you cannot follow along while another is reading from

a different version, though sometimes there are differences. The differences you

are reading in English are most often the difference in the English vocabulary

rather than the difference between Greek words. The third and smallest group of

manuscripts is known as the Western text, “W” in chart 1. There is no commonly

used English version based upon this free and paraphrastic text. The Greek

manuscript tradition of the Western text died out when the Vulgate became

popular which replaced it in the West as it retained some of its readings.

Why did the M group begin to have so many copies beginning with the ninth century? Why did group A begin to dwindle out in the ninth century?

By 632AD the Muslims had conquered much of the Arabian Peninsula. By 750AD they expanded greatly as the map shows. It is not hard to understand what transpired when the Muslims invaded Palestine and Egypt; those churches became much smaller and under duress. Therefore the Alexandrian type of text dwindled along with the churches in those regions. Also notice that the Byzantine Empire withstood the Muslim invasion, from 750AD to 1453AD. It is no wonder we have an abundance of manuscripts from Byzantium in this later period. The Byzantium text type is also known as the Majority text; in chart 1 is labeled the M text.

Having overviewed the textual tradition, we return once more to Erasmus. What manuscripts were available to Erasmus back in 1516AD to base his Greek Text upon? Erasmus had a half a dozen manuscripts to compare in producing his printed Greek Text which became the standard Greek Text. “Erasmus had 3 manuscripts of the Gospels and Acts; 4 manuscripts of the Pauline Epistles; and only 1 manuscript of Revelation.”(Combs, 1996) These manuscripts date back to the 12-15th century generally. The King James translators relied heavily upon the Greek text of Erasmus but not solely on Erasmus. They also had another printed Greek Text to rely upon, that of Theodore Beza, his 1598AD edition. So all together they translated from a Greek text based upon about 25 Greek manuscripts (Lewis, 1982). These 25 Greek manuscripts are not old, but generally go back to the 12th-15th centuries. Yet these were the manuscripts available and accessible to the translators of the KJV. After the KJV was completed in 1611AD the Textus Receptus was printed, twenty some years later, in 1633AD. The two Elzevir brothers, who were printers, published a convenient edition of the Greek NT with a “blurb” that read, “the text now received by all, in which we give nothing changed or corrupted” (Metzger & Ehrman, 2005). From this point on it was the text received by all, the “Textus Receptus”. This same text was reprinted by many thereafter with each scholar’s personal notes. “As it happened, Stephanus’ third edition became for many persons, especially in England, the received or standard text of the Greek Testament” (Metzger & Ehrman, 2005).

More Ancient Manuscripts, after the King James Version:

After the completion of the KJV there were many manuscripts being found and compared to this standard text, the Textus Receptus. Some of these manuscripts were almost 1000 years earlier. Scholars continued to print the Textus Receptus, but adding more and more of their notes that referred to older readings of earlier manuscripts. As time and manuscripts began to accumulate more editions came out, but no one was willing to print a different Greek Text than the Textus Receptus. John Mill produced a Textus Receptus that had 30,000 variant readings from 100 manuscripts; the text was printed around 1707AD. But it was Karl Lachmann in 1831 who finally took courage to dethrone the Textus Receptus and print a different Greek Text from the wording found in the manuscripts of the 4th century. By the mid-1800’s we have arrived at a critical period where scholars, almost universally, were willing to abandoned the late manuscripts of the Textus Receptus and begin to invest in the early manuscripts of group “A”, the Alexandrian type of text. Men such as Griesbach (1745-1812), Tregelles (1813-1875), and Tishendorf (1815-74), were convinced that the older manuscripts contained the readings that were closer to the originals. This took time, investigation, and affirmation to the next generation who were reluctant to leave their KJV and its underlying Textus Receptus.

Westcott and Hort:

“The year 1881 was the marked by the publication of the most noteworthy critical edition of the Greek Testament ever produced by British scholarship. After working about 28 years on this edition (from about 1853 to 1881), Brooke Foss Westcott (1825-1901)... and Fenton John Anthony Hort (1828-92)... issued two volumes entitled The New Testament in the Original Greek”(Metzger & Ehrman, 2005). Professor Hort wrote the introduction by which he laid down the principles and method they used in producing their Greek Text. These same methods are being used today. They realized that ten manuscripts could simply be copied from one manuscript. Therefore the ten copies should be treated as one witness, not ten. They also put manuscripts into large groups like chart 1 above, although they used different names for these groups, as well as one additional grouping. Also it was understood that when later scribes who had two exemplar manuscripts before them, they often did not like choosing between two different readings. So, instead of choosing, they often put them together into a longer reading. Then that longer reading was copied for the next generation. There were many other observations that Hort made in his introduction that greatly aided the next generation of scholars.

In the end, Westcott and Hort took two highly valued manuscripts, the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, both located in the “A” group above, and where these two manuscripts agree was the basis of their Greek text, for the most part. Philip Comfort writes, “In my opinion, the text produced by Westcott and Hort (The New Testament in the Original Greek) is still to this day, even with so many more manuscript discoveries, a very close reproduction of the primitive text of the New Testament. Of course, I think that they gave too much weight to Codex Vaticanus alone, and this needs to be tempered. This criticism aside, the Westcott and Hort text is extremely reliable. I came to this conclusion after doing my own textual studies. In many instances where I would disagree with the wording of the Nestle/USB text in favor of a particular variant reading, I would later check with Westcott and Hort text and realize that they had often come to the same decision. This revealed to me that I was working on the same methodological basis as they. Of course, the manuscript discoveries of the past one hundred years have changed things, but it is remarkable how often they have affirmed the decisions of Westcott and Hort” (Comfort, 2005). One of the manuscripts found since Westcott and Hort is P75, that is papyri 75, dated about 175-200AD which reads extremely close to Vaticanus, pushing the text of Westcott and Hort into the 2nd century AD and in many ways affirming that Westcott and Hort were correct in their underlying assumptions. Westcott and Hort do not mention the papyri manuscripts, which today number up to 127. They used about 45 Uncial/Majuscule manuscripts (which are written in all uppercase letters written upon parchment or velum), whereas today there are over 290 (Clarke, 1997). Also, early manuscripts written in other languages, as well as more accurate Patristic quotations have been supplemented since Westcott and Hort.

The Majority Text:

There have been a few scholars who disapprove of going to the early manuscripts, those dated from the second century to the middle fourth century, to find the basis for a printed Greek Text, the “A” group. They would rather pick the manuscripts from the M group in chart 1. These scholars realize that this M group or Byzantine type of manuscript is found only in the beginning in the 5th century, prior to that there is no Byzantine type of manuscript which has survived. So the name “Majority Text” is a misnomer in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries. The “A” type of text in chart 1, the Alexandrian type, is in fact the majority text early on, but today no one calls the Alexandrian text the majority text. So what is called today as the Majority Text is the minority text until about the 9th century, please see chart 1. Daniel Wallace further states, “So far as I am aware, in the last eighty years every critical study on patristic usage has concluded that the Majority text was never the text used by the Church Fathers in the first three centuries. (2) Though some of the Fathers from the first three centuries had isolated Byzantine readings, the earliest Church Father to use the Byzantine text was Asterius, a fourth-century writer from Antioch” (Wallace, 1995).

There are two Greek Majority texts that have been printed, one done by Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad, The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text, 1982 and one done by William G. Pierpont and Maurice A. Robinson, The New Testament in the Original Greek According to the Byzantine/Majority Textform, 1991, updated 2005. Many of these scholars who endorse the Byzantine text do so on the basis of a theological argument, that God providentially had this type of manuscript available to more people throughout history. But in making such an argument they gloss over the period from the 2nd century to 8th century where this text was not providentially the majority.

The NA26/27 and UBS3/4 editions of the Greek Text:

Most college students for the past couple of decades have been using the United Bible Society text (UBS), of the 3rd (corrected) -1983, or 4th edition -1993, or the Nestle-Aland text of the 26th -1979, or 27th edition -1993. These four editions have exactly the same Greek wording, the same Greek text. The punctuation is different between these two editions, the textual notes are very different, but the Greek words are exactly the same. The Nestle-Aland27, abbreviated NA27, cites about 15,000 variants in the text and is a more scholarly edition in the apparatus, that is in its footnote-like section on the bottom of each page. That may seem like a lot of variants, but I will put this into perspective later on. The apparatus cites key manuscripts that support the text or supports a variant that didn’t make it into the printed text. In contrast the UBS Greek text has only about 1400 variants in its apparatus, and although this apparatus cites far fewer variants, each variant is given more manuscript information.

This Greek text, NA26/27 and UBS3/4, is based upon manuscripts found in Group A for the most part, the Alexandrian text-type. This text has been the starting point for many modern versions (ESV, NASB, NET, NRSV, etc.), though each version does not follow this Greek Text completely.

It also should be noted that there are a few sections in this Greek text that have been enclosed with double brackets [[ ... ]]. These sections indicate, “that the enclosed words, generally of some length are known not to be a part of the original text...” (UBS, intro. p.2). Some of these include the account of the adulteress (John 7:53-8:11), the ending of (Mark 16:9-20), the angel and sweat like blood in (Luke 22:43-44) and the confession of the Ethiopian (Acts 8:37). Different English versions treat the above passages differently, some simply place a marginal note showing the text has weak or only late manuscript support, others put some of these texts in the side margin, others put [ ] brackets around the text identifying to the careful reader that this portion of the text does not have early manuscript support.

The goal of the UBS Greek Text has been towards translators “throughout the world”. In this regard, it notes the variants that would possibly make a difference in translation. Most variants do not affect translation at all as you will see shortly. The UBS3 edition cites 1444 variants, the USB4 cites 1438 variants. The USB4 has removed 273 variants and added 284 new variants. The UBS apparatus gives each variant reading a rating of either, A, B, C, or D as a guide for the certainty of the text. Where “A” indicates that the text is certain, “B” indicates that the text is almost certain, “C” indicates that the committee had difficulty in deciding which variant to place in the text, and “D” indicates that the committee had great difficulty arriving at a decision (UBS, intro. p.3).

It is rather interesting that there has been a “textual optimism” growing from the UBS third corrected edition in 1983, to the UBS fourth edition in 1993, for the graded text. This means that there are far more “A” ratings in the 4th edition than in the 3rd edition, showing more certainty by its editors. Kent Clarke explores the reasons for this dramatic upgrade in the certainty of the text as he looks for the manuscript evidence cited in both editions. Note the dramatic increase of A’s and the dramatic decrease of “C”s and “D”s from the third edition to the fourth edition.

UBS3 has 126 “A” ratings, the USB4 has 514.

UBS3 has 475 “B” ratings, the USB4 has 541.

UBS3 has 669 “C” ratings, the USB4 has 367.

UBS3 has 144 “D” ratings, the USB4 has 9. (Clarke, 1997)

It is obvious that from 1983 to 1993 the members of this committee, which has seen some change in membership, have become more confident in this printed Greek text. This is encouraging to observe the growing confidence of these textual scholars. The explanations for this growing optimism between the 3rd corrected and 4th editions have not been explained very adequately according to Kent Clarke.

Getting a Perspective

Now that we have briefly highlighted the history of Textus Receptus, Westcott and Hort, Majority Text, and the NA26/27 and UBS3/4 editions of the Greek Text, let us get a perspective on the differences. My BibleWorks computer software will in just over a second compare all the differences between these four different Greek Texts. Let us take brief look to see how similar these four Greek Texts are. In the chart below I will look at all the differences between these four texts in Matthew chapter one only. Mathew chapter two has fewer variants than chapter one.

In the chart below the TR = Textus Receptus, M = Majority Text of Robinson-Pierpont (1995), WH= Westcott and Hort, NU= NA26/27 and UBS3/4 editions of the Greek Text. Matthew chapter one has 25 verses. In the first chart below all the verses that have the same exact wording for all the words in each verse, and the number of Greek words in that verse. I will not include the moveable “nu” that looks like a “v”, as a difference, for this is a common difference in spelling only. This is not to say that there are not variants in these verses below because there are some, but rather these five committees using different sets of manuscripts have concluded that this represents what the initial text according to the set of manuscripts they used. NU represents two committees, that of the Nestle-Aland text (N) and that of the United Bible Society (U).

Mat. 1:2 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 18 words

Mat. 1:3 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 21 words

Mat. 1:4 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 15 words

Mat. 1:12 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 14 words

Mat. 1:16 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 15 words

Mat. 1:21 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 19 words

Mat. 1:23 TR, M, WH, NU; Exactly the same 22 words

Remember the manuscripts for the TR come from about 25 manuscripts from the 12-15th century generally. The Majority text comes from the manuscripts beginning from the 5th century to the 15th century. The WH text comes from a few manuscripts from the 4th century and a few additional manuscripts located mainly in the Alexandrian family. The NU text is also from the Alexandrian family now supported and supplemented with the additional papyri. This shows that the Greek Text is far more consistent through the centuries than some might think. Secondly, this shows that the Greek Text in these five editions in these verses above is the same, but our English translations use different English vocabulary in these verses. The variety in English translations in the above verses is the English, not the Greek.

Now we will look at the differences of these five Greek texts from Matthew chapter one. You may want to just skim over these, but it does give you an idea of how close these Greek texts read even when they are different.

1:1 TR (Δαβίδ) , M (Δαυίδ), WH (Δαυεὶδ), NU (Δαυὶδ)

So the name “David” is spelled three different ways, the 7 other words in this verse are exactly the same in all 5 Greek Texts.

1:5 TR (Βοὸζ), M (Βοὸζ), WH (Βοὲς), NU (Βοὲς)

So the name “Boaz” is spelled 2 different ways (2 times per verse 5).

1:5 TR (Ὠβὴ), M (Ὠβὴ), WH (Ἰωβὴδ), NU (Ἰωβὴδ)

So the name Obed is spelled two different ways (2 times per verse 5). The17 remaining words are exactly the same.

1:6 TR (Δαβὶδ), M (Δαυὶδ), WH (Δαυεὶδ), NU (Δαυὶδ)

So the name David is spelled three different ways (2 times per verse 6).

1:6 TR (Σολομῶντα), M (Σολομῶνα), WH (Σολομῶνα), NU (Σολομῶνα)

So the name Solomon is spelled two different ways.

1:6 TR (ὁ βασιλεὺς), M (ὁ βασιλεὺς), WH (omit), NU (omit)

So here is the first real difference of chapter 1, “the king” is contained in the TR, M Texts but the WH and NU do not contain these two words. The earliest manuscripts do not contain these words. The remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:7 TR (Ἀσά), M (Ἀσά), WH (Ἀσάφ), NU (Ἀσάφ)

So the name “Asa” is spelled two different ways. The 14 remaining words are exactly the same.

Now I will overview:

1:8 Asa & Uzziah are spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:9 Uzziah and Ahaz are spelled differently; remaining 12 words are exactly the same.

1:10 Amos and Josiah are spelled differently; remaining 12 words are exactly the same.

1:11 Josiah are spelled differently, remaining 12 words are exactly the same.

1:13 Eliakim is spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:14 Achim is spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1:15 Mathan is spelled differently; remaining 13 words are exactly the same.

1: 17 David is spelled differently, remaining 27 words are exactly the same.

1:18 TR (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ), M (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ), WH ([Ἰησοῦ] Χριστοῦ), NU (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ)

So the WH text reads “[Jesus] Christ” like the other three texts do, but brackets the name [Jesus]. There is a 7th century manuscript that does not contain the name Jesus in this verse.

1:18 TR (γέννησις), M (γέννησις), WH (γένησις), NU (γένησις)

So there is one letter difference here between these two words. The TR & M read “birth” and the WH & NU read “birth, origin”. So these words are often translated the same.

1:18 TR (γὰρ), M (γὰρ), WH (omit), NU (omit)

So the TR & M text reads “for”, yet this is almost not translatable in this passage. The first manuscript that contains “for” is a sixth century manuscript. The remaining 25 words are exactly the same in all four Greek Texts.

1:19 TR (παραδειγματίσαι), M (παραδειγματίσαι) , WH (δειγματίσαι), NU (δειγματίσαι)

So these two words are very similar, but with the preposition (παρα) added to the front of the word in the TR & M texts. These two different Greek words are closely related, and are most often translated the same. The remaining 15 words are exactly the same.

1:20 David and Mary are spelled differently; the remaining 29 words are exactly the same.

1:22 TR (τοῦ Κυρίου), M (τοῦ Κυρίου), WH (Κυρίου), NU (Κυρίου)

So the TR & M text has the definite article “the” before the word “Lord”, and reads “the Lord”. The WH and NU does not have the definite article “the” before the word “Lord”, yet because it is still definite, it is still translated “the Lord”. The remaining 14 words are exactly the same.

1:24 TR (διεγερθεὶ), M (διεγερθεὶ), WH (ἐγερθεὶς), NU (ἐγερθεὶς)

So the two different Greek words are almost the same, the preposition (δια) is added to (ἐγερθεὶς) in the TR & M texts, but both words are most often translated the same. The remaining 18 words are exactly the same.

1:25 TR (τὸν υἱὸν αὐτῆς τὸν πρωτότοκον), M (τὸν υἱὸν αὐτῆς τὸν πρωτότοκον) , WH (υἱὸν), NU (υἱὸν); Here the TR & M text reads, “her firstborn son” where WH & NU simply reads “a son”. The earliest manuscripts read “a son”. The remaining 14 words are exactly the same.