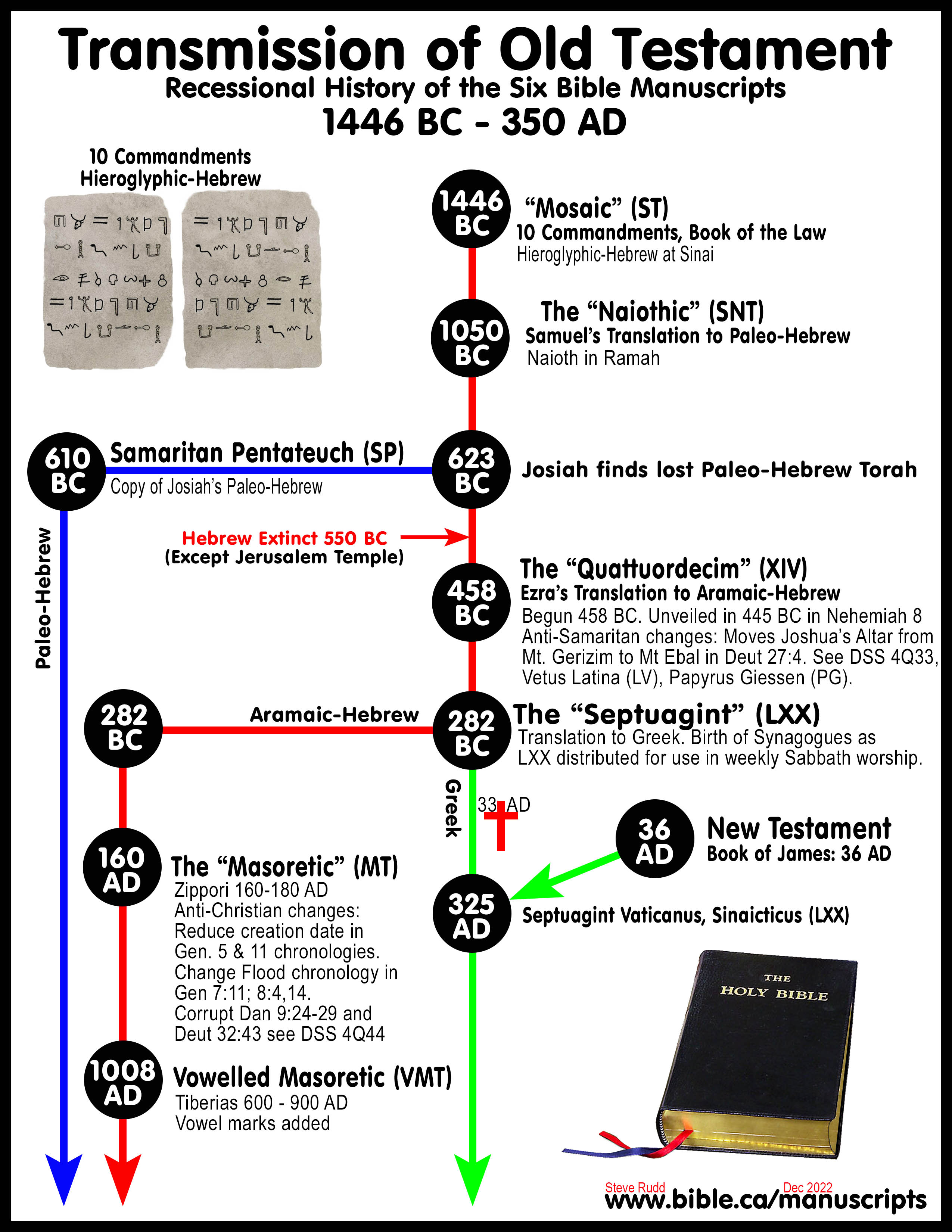

Manuscript Transmission of the Old Testament

Recensional history of the Six Bible Manuscripts of the Old Testament

Mosaic | Naiothic | Samaritan Pentateuch | Quattuordecim | Septuagint | Masoretic

"Scripture cannot be broken" (Jesus, John 10:35)

Steve Rudd 1017

|

Six Manuscripts of the Old Testament |

|||||

|

Name |

Date |

Authors |

Place |

Content |

Language |

|

Mosaic (ST) |

1446 BC |

Moses |

Sinai |

Book of the Law, Torah |

Hieroglyphic Hebrew |

|

Naiothic (SNT) |

1050 BC |

Samuel |

Naioth, Ramah |

Torah, Joshua |

Paleo-Hebrew |

|

Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) |

623/610 BC |

Samuel |

Naioth, Ramah |

Torah (copy from Josiah) |

Paleo-Hebrew |

|

Quattuordecim (XIV) |

458-445 BC |

Ezra “the 14” |

Jerusalem |

Tanakh, (Except Neh., Mal.) |

Aramaic-Hebrew |

|

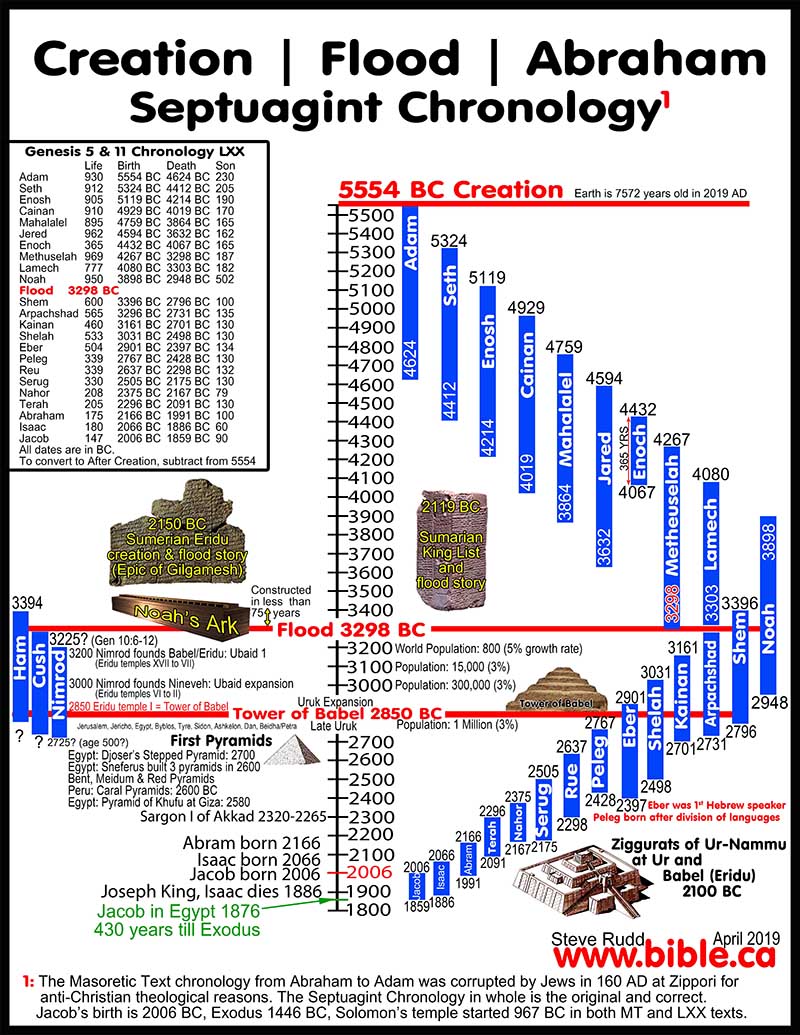

Septuagint (LXX) |

282 BC |

“the 70” |

Alexandria |

Tanakh |

Greek |

|

Masoretic (MT) |

160 AD |

Rabbi Yose ben Halafta |

Zippori |

Tanakh |

Aramaic-Hebrew |

Introduction:

1. There have been six different Manuscripts of the Old Testament:

|

Six Manuscripts of the Old Testament |

|||||

|

Name |

Date |

Authors |

Place |

Content |

Language |

|

Mosaic (ST) |

1446 BC |

Moses |

Sinai |

Book of the Law, Torah |

Hieroglyphic Hebrew |

|

Naiothic (SN) |

1050 BC |

Samuel |

Naioth, Ramah |

Torah, Joshua |

Paleo-Hebrew |

|

Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) |

623/610 BC |

Samuel |

Naioth, Ramah |

Torah (copy from Josiah) |

Paleo-Hebrew |

|

Quattuordecim (XIV) |

458-445 BC |

Ezra “the 14” |

Jerusalem |

Tanakh, (Except Neh., Mal.) |

Aramaic-Hebrew |

|

Septuagint (LXX) |

282 BC |

“the 70” |

Alexandria |

Tanakh |

Greek |

|

Masoretic (MT) |

160 AD |

Rabbi Yose ben Halafta |

Zippori |

Tanakh |

Aramaic-Hebrew |

I. Recensional history of the Septuagint:

- Transmission-history of the Septuagint:

- Translation begins in Egypt around 280 BC (Old Greek)

- Proto-Lucian recension of the "Old Greek" in the second or first century b.c. to conform to a Palestinian Hebrew text. (this Hebrew text is not the Masoretic Text of the 10th century AD, but may be an ancient parent copy like the "Proto-Masoretic" text.)

- Proto-Theodotionic/KR (of the Old Greek or proto-Lucian?) at the beginning of the Christian era to conform to the proto-Masoretic text.

- Recensions by Aquila, Theodotion, and probably Symmachus of the KR in the second century a.d. to conform to the Masoretic text.

- Christian recensions by Origen, Lucian, and Hesychius in the third century a.d.

- Above points from: (The Transmission-History of the Septuagint. W. W. Combs, Bibliotheca Sacra, 146, p268, 1989 AD)

- "RECENSIONAL ACTIVITY BEFORE THE CHRISTIAN ERA: To understand the development of the Septuagint during this period it is necessary first to discuss the evolution of the Hebrew text. Building on the foundation of Albright and from his own studies of the Qumran materials, Cross has developed a theory of local texts with regard to the Hebrew Old Testament. In the period between the fifth and first centuries b.c., three distinct text-types developed in Palestine, Egypt, and Babylon. The Palestinian was the text-type current in Palestine at the end of the fifth century. Most of the Hebrew witnesses from Qumran as well as the Samaritan Pentateuch belong to this textual family. The Egyptian text is a branch of the Palestinian which was taken to Egypt in the fifth to fourth centuries b.c. and became the basis for the Septuagint. The Babylonian text developed in the Jewish community that remained in Babylon after the return of Ezra. This form of text was probably introduced into Palestine in the second century b.c. and became the basis for the Masoretic text. All three text-types are present at Qumran. When users of the Septuagint found that it did not always agree with the form of Hebrew text they were using, it is understandable that they would seek to bring it into line with the Hebrew text. In fact most known recensions of the Septuagint were for the purpose of harmonizing it with the then-current form of Hebrew text. The first known recensional activity of this kind is commonly called proto-Lucian. It was a recension of the Old Greek in the second or first century b.c. to conform to the Palestinian Hebrew text-type. The evidence for this recension was first presented by Cross: "In studying that text of 4QSama, I have been forced to note a series of readings in which the Hebrew of 4QSama reflects the so-called Lucianic recension preserved in the Greek minuscules boc2e2, and the Itala. In other words, 4QSama stands with LXXL against MT and LXXB. These are proper proto-Lucianic readings in a Hebrew text of the first century b.c., four centuries before the Syrian Father to whom the recension is attributed." (The Transmission-History of the Septuagint. W. W. Combs, Bibliotheca Sacra, 146, p263, 1989 AD)

- RECENSIONAL ACTIVITY IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. The next known recensions of the Septuagint were those by Aquila [Aquila of Sinope ~130 AD], Theodotion, and Symmachus. Scholars once thought these were independent translations, but it is now thought that Aquila and Theodotion and probably Symmachus were recensions of the KR. Each of these sought to bring the KR into agreement with the current form of the Hebrew text, which by the second century was almost identical with the later Masoretic text. According to tradition, Aquila, a relative of the Emperor Hadrian, was converted to Christianity when he came to Jerusalem. Because he refused to give up some of his pagan practices, he was excommunicated and then became a proselyte to Judaism. Having studied with Rabbi Aqiba, Aquila produced his revision of the Septuagint about 130 a.d., using the exegetical principles of his famous teacher. Aquila’s version is known for its “extreme literalness and for its translation of Hebrew verbal roots in all their nominal and verbal derivatives by a single Greek stem.” The most well-known characteristic of Aquila is the rendering of אֶת, the sign of the definite accusative in Hebrew (usually untranslated), by the preposition σύν. This practice has been ridiculed by scholars from Jerome onward. The rules governing Aquila’s translation of אֶת have now been worked out by Barthélemy, who shows that the use of σύν as an adverb, primarily in Homer, is at the base of Aquila’s translation technique. Interestingly Aquila’s version of Ecclesiastes has replaced the original Septuagint in extant manuscripts of the Septuagint. Since it has been previously shown that the recensional material associated with the name Theodotion is to be considered part of the proto-Theodotion/KR, one wonders if there is anything left for the traditional second-century translator. He is usually identified as a Jew of the Dispersion or a Jewish proselyte who came from Ephesus. Most scholars feel that he cannot be dismissed entirely, since his existence as a reviser of the Septuagint is historically well established. Therefore it is probable that his work involved only a slight reworking of the proto-Theodotion/KR. Shenkel suggests that Theodotion’s recension can be distinguished from proto-Theodotion by the former’s greater fidelity to the Masoretic text. Modern scholarship has been able to add little to the knowledge of the recension of Symmachus. He is generally thought to have been a Jewish convert to Ebionite teaching. Wevers says that his work can “easily be recognized by its elegant and bombastic style.” His recension, which is to be dated at the end of the second century, has survived only in remains of the Hexapla. Barthélemy believes that the KR was the basis for Symmachus’ recension. (The Transmission-History of the Septuagint. W. W. Combs, Bibliotheca Sacra, 146, p265, 1989 AD)

- RECENSIONAL ACTIVITY IN THE THIRD CENTURY A.D. Up until the third century a.d. all known recensional activity with regard to the Septuagint was done by Jews or Jewish proselytes. But in the third century three Christian recensions were produced by Origen, Lucian, and Hesychius. Origen’s recension was part of his monumental work, the Hexapla. "Origen arranged the Hebrew and Greek texts at his disposal into a six-column Bible (230–245). In the first column, he recorded the Hebrew text of his day; in the second, the Hebrew in Greek transliteration; in the third, Aquila; in the fourth, Symmachus; in the fifth, the LXX; and in the sixth, Theodotion. Whenever the LXX contained an expression that was not in the Hebrew Bible of his day, Origen marked that Greek reading with an obelus (÷) at the beginning and a metobelus (:) at the end. Whenever the LXX lacked an equivalent for a reading in the Hebrew Bible, he added such a Greek equivalent to his fifth column (usually … from Theodotion) and marked it with an asterisk at the beginning and a metobelus at the end. Thus one could read the fifth column with its notations and figure out how it compared with the Hebrew." (Klein, Textual Criticism of the Old Testament: The Septuagint after Qumran, p. 7.) For some Old Testament books Origen had access to three other Greek versions called Quinta, Sexta, and Septima. Little is known about them except that recently Barthélemy has identified the Quinta in Psalms with the KR. Most scholars have concluded that the primary purpose of the Hexapla was to establish the correct text of the Septuagint, which Origen incorrectly assumed was what most closely agreed with the Hebrew text current in his day. Thus the fifth column of the Hexapla, called the “Hexaplaric” or “Palestinian” recension, was a Greek text consistently corrected to the Masoretic text. Brock, however, has argued that Origen was not trying to reconstruct the original text of the Septuagint, but that the Hexapla was a tool for the Christian controversialist in debates with the Jews. Whatever his purpose, the result of Origen’s labors has been to bring confusion to the textual history of the Septuagint. The Hexapla was too large (about 6,500 pages) to be copied, so most of the time only Origen’s reconstructed fifth column was copied, but usually without the asterisks and obeli. Thus a very corrupt form of text began to circulate. Many extant manuscripts display this so-called “hexaplaric” text. Another factor that adds to the confusion is that Origen did not always know the identity of the sources which he used. It is now known that the books of Samuel-Kings and the Minor Prophets in the sixth column are not the work of Theodotion. Also it has been suggested that Origen himself may have been responsible for replacing the original Septuagint in Daniel with Theodotion’s version. The entire Hexapla is not extant; it presumably was destroyed when the Saracens invaded Caesarea in 638. Fortunately a few years earlier the fifth column had been translated into Syriac by Paul of Tella. This so-called “Syro-Hexaplar” carefully reproduces Origen’s critical signs. Other fragments of the Hexapla have survived, and a collection of them was made by Frederick Field at the turn of the 20th century. In his preface to Chronicles in the Vulgate (a.d. 400), Jerome mentioned that the Hesychian recension was used in Egypt and the Lucian was used from Constantinople to Antioch. Little is known about the Hesychian recension except that it is thought to have been the work of a little-known Bishop Hesychius at the end of the third century. The question of which extant manuscripts, if any, contain this recension is sharply debated. The recension usually identified with Lucian, the third-century presbyter of Antioch, has been shown to contain an earlier stratum called “proto-Lucian.” Apparently the traditional Lucian began with the work of proto-Lucian and added material from the Hexapla. Thus his work is usually characterized by comprehensiveness: “Lucian filled in various kinds of omissions, preserved both readings (conflation) in cases where manuscripts had variants, replaced pronouns with proper names, and made various grammatical changes, including replacement of Hellenistic with Attic forms.” (The Transmission-History of the Septuagint. W. W. Combs, Bibliotheca Sacra, 146, p265, 1989 AD)

|

The Septuagint LXX “Scripture Cannot Be Broken” |

|||||

|

Start Here: Master Introduction and Index |

|||||

|

Six Bible Manuscripts |

|||||

|

1446 BC Sinai Text (ST) |

1050 BC Samuel’s Text (SNT) |

623 BC Samaritan (SP) |

458 BC Ezra’s Text (XIV) |

282 BC Septuagint (LXX) |

160 AD Masoretic (MT) |

|

Research Tools |

|||||

|

Steve Rudd, November 2017 AD: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections |

|||||

By Steve Rudd: November 2017: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Go to: Main Bible Manuscripts Page

Go to: Main Ancient Synagogue Start Page