10 Archeological proofs the Septuagint Tanakh was translated by Jews before 150 BC

150 BC: Completion of Greek Tanakh (Gen – Malachi)

The entire Hebrew Old Testament (Tanakh) was fully translated by Jews into Greek by 150 BC

The Greek Septuagint LXX

"Scripture cannot be broken" (Jesus, John 10:35)

Steve Rudd 2017

Modern Jewish “anti-Christian” Rabbis, like Tovia Singer attack Christianity with the historical lie and falsehood that the Septuagint did not exist at the time of Christ but was a product of the Byzantine church designed to convert Jews. Indeed! Singer knows that if the Septuagint Tanakh were a Jewish translation in every synagogue in the world at 150 BC, he would have no choice but to convert to Christianity! The Septuagint was the most powerful evangelizing tool of the earliest Christians precisely because the first Christians were Jews who knew the Septuagint was universally considered equal to the Hebrew original by all Jews including the High priest in Jerusalem! Archeology has confirmed that while the 5 books of Moses (Torah) were the first to be translated in 282 BC into Greek as the Septuagint, the entire Old Testament (Tanakh) had been translated and was is full circulation by 150 BC. This is the view of one of the top Septuagint scholars in the world is Emanuel Tov, a Jewish emeritus professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. We have highlighted 10 archeological proofs that the Greek Tanakh was 100% complete and that the Septuagint was the standard “pulpit bible” in every Synagogue: footnote to the Greek Esther dates the book to 176 BC, Eupolemos quotes Greek/LXX Chronicles in 150 BC, Aristeas The Exegete quotes Greek/LXX Job in 150 BC, Prologue from the Wisdom of Sirach/Sira/Ecclesiasticus flatly states the entire Old Testament had been translated into Greek in 132 BC, Letter of Aristeas 155 quotes Greek/LXX Job 42:3 in 130 BC, The 32 foot long Greek/LXX scroll of the 12 minor prophets (8HevXIIgr) dates to 50 BC. Of special importance is the Greek Minor prophets scroll found at Nahal Hever (8HevXIIgr) because here, the Jews inserted Paleo-Hebrew into the Greek text out of respect for the name of God: YHWH. Christians simply would never do this, proving the Greek minor prophets scroll was a Jewish Greek translation long before Christ was born. A large number of Jewish apocalyptic documents translated into Greek around 50 BC, Greek fragment of “Epistle of Jeremiah” (not the book of Jeremiah) discovered at Qumran dating to 50 BC, Hebrew manuscript of the shorter LXX version of Jeremiah the prophet found at Qumran, Philo quotes extensively from most books of the Greek Tanakh in 30 BC including Isaiah 5 times. Philo also uses the longer Chronological numbers of the LXX in Gen 5&11 and copies the LXX in saying 75 entered Egypt with Jacob, whereas the Hebrew Masoretic text says 70. Josephus 70 AD, mentions Jesus and also copies the longer chronological numbers of Gen 5&11 from the Septuagint!

Introduction:

1. After Ptolemy II commissioned the translation of the Hebrew Torah (Gen-Deut) into Greek for the Library of Alexandria in 282 BC all the remaining books (Joshua – Malachi) were fully translated into Greek as early as 250 BC but not any later than 150 BC.

2. We know from archeology, that all rest of the Old Testament post-Pentateuchal books (ie. Joshua to Malachi) were fully translated into Greek by 150 BC:

a. The eminent Jewish Septuagint scholar Emanuel Tov dates the pre-Christian era manuscript of the Greek translation of Isaiah (LXX) to 170 BC because it contains allusions to historical situations and events that point to the years 170-150 BCE.

b. This is important because it proves the Greek copies of Isaiah we have today, really were translated by Jews not Christians, centuries before the birth of Christ.

3. Jewish Rabbi apologists fabricate a false Jewish history that first century Jewish synagogues DID NOT use the Septuagint (Greek Tanakh) as their standard biblical text. They also teach the lie that Jews never translated the entire Old Testament into Greek long before Jesus was born.

a. “Rabid Rabbis” like Tovia Singer, know that if the Septuagint Tanakh was a Jewish translation before Christ, then they might as well convert to Christianity because the word “Virgin” in LXX Isa 7:14 was chosen by Jews in 200 BC not Christians in 400 AD.

b. There is not a Septuagint Scholar alive who agrees with Tovia Singer’s revisionist Jewish history.

I. Archeological evidence the Tanakh was fully translated into Greek before 150 BC:

1. 176 BC: “The footnote to the Greek Esther, which states that that book was brought to Egypt in the 4th year of “Ptolemy and Cleopatra” (probably i.e. of Ptolemy Philometor: 176 BC), may have been written with the purpose of giving Palestinian sanction to the Greek version of that book; but it vouches for the fact that the version was in circulation before the end of the second century b.c. (An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, H. B. Swete, p24, 1914 AD)

2. In 150 BC: Eupolemos of 1 Macc. 8:17 quotes Chronicles from the LXX.

3. In 150 BC: Aristeas The Exegete quotes extensively from the Greek book of Job:

a. "Aristeas (not the pseudonymous author of the letter, but the writer of a treatise περὶ Ἰουδαίων) quotes the book of Job according to the lxx., and has been suspected of being the author of the remarkable codicil attached to it: Job 42:17 b–e.” (An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, H. B. Swete, p24, 1914 AD)

b. “A Jewish author who flourished prior to the mid-1st century b.c.e. whose work On the Jews treated, at the very least, the biblical figure Job. To what extent he treated other matters is not known. He is generally designated “exegete” or “historian” because of his interest in the biblical text, especially its historical and genealogical features. This designation also serves to distinguish him from the author of the Letter of Aristeas to Philocrates, which relates the story of the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek” (ABD, Aristeas The Exegete)

4. 132 BC: The apocryphal book "Wisdom of Sirach/Sira, Ecclesiasticus [Latin]" was written by Jesus Ben Sirach in Jerusalem c. 200-175 BC in Hebrew then translated into Greek by his grandson c. 132-100 BC.

a. ORIGINAL PROLOGUE: "You are invited therefore to read it [Greek translation of Ecclesiasticus] with goodwill and attention, and to be indulgent in cases where, despite our diligent labor in translating, we may seem to have rendered some phrases imperfectly. For what was originally expressed in Hebrew does not have exactly the same sense when translated into another language. Not only this book, but even the Law itself, the Prophecies, and the rest of the books differ not a little when read in the original. (Wisdom of Sirach/Sira, Ecclesiasticus [Latin], prologue of translator)

b. “The books in the Prophets and Writings were translated later, probably all of them by about 130 b.c. as suggested by the Greek Prologue to Ben Sira." (The Septuagint and the Text of the Old Testament, P. J. Gentry, Bulletin for Biblical Research, Vol. 16, p 193, 2006 AD)

c. "Old Greek and later Greek versions. Old Greek or Septuagint refers to a translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. The Pentateuch was translated early in the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-240 BC) in Alexandria, Egypt. The evidence of the Prologue to Ben Sira suggests that almost all the remaining books were translated by 130 BC. The name septuaginta, or "the Seventy," is adapted from propaganda that the Torah was translated by seventy-two scholars from Palestine (Aristeas)." (The Text of the Old Testament, Peter J. Gentry, Journal Of The Evangelical Theological Society, 52/1, p24, March 2009)

d. "The knowledge that we have from other sources of the reign of Ptolemy II make this hypothesis likely, and in 132 bce the translator of the book of Sira already alludes in the prologue to the Torah, the Prophecies and other writings as integral parts of the Alexandrian Bible." (The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, Marcos, N. Fernández, p40, 2000 AD)

e. The translator of Ecclesiasticus in his prologue clearly states that the entire tripartite division of the Hebrew canon (Law, Prophets, Writings) had been translated into Greek by 132 BC.

f. Jesus also referred to the Old Testament with the same tripartite formula in Luke 24:44. (Law, Prophets, Psalms).

g. This unique three divisions formula is the one that was transmitted by the Masoretes which produced the oldest Hebrew manuscript on earth that dates to 1008 AD underlying most modern Bibles.

h. "The Canon in the Jewish Diaspora: THE PROLOGUE OF JESUS BEN SIRACH [132 BC]: In connection with the question of the development of the Jewish canon, reference is repeatedly made to the Prologue by the author’s grandson, who was also the translator of Sirach. The author speaks three times of a threefold division of the Jewish Scriptures. The very first sentence reads: "Whereas many great teachings have been given to us through the law, the prophets, and the other [writings] that followed them … (διὰ τοῦ νόμου καὶ τῶν προφητῶν καὶ τῶν ἄλλων τῶν κατʼ αὐτοὺς ἠκολουθηκότων)." The next references occur in the description of the activity of his grandfather, who "devote[d] himself especially to the reading of the law and the prophets and the other books of our fathers (ἐπὶ πλεῖον ἑαυτὸν δοὺς εὶς τε τὴν τοῦ νόμου καὶ τῶν προφητῶν καὶ τῶν ἄλλων πατρίων βιβλίων ἀνάγνωσιν)." The final reference occurs after he has mentioned the difference between the Hebrew original and the imperfect translation: "Not only this [work], but even the law itself, the prophecies and the rest of the books differ not a little if read in the original (ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτὸς ὁ νόμος καὶ οἱ προφῆται καὶ τὰ λοιπὰ τῶν βιβλίων)." Clearly, the grandson, who himself emigrated from Palestine to Egypt in the year 132, reproduces here the Hebrew concept of canon, although we do not know exactly which books he placed among ‘the other books’. His threefold repetition and the concluding statement that he had published his book for those ‘abroad who are eager to learn’, who ‘desire to lead a life according to the law’, suggest that he regarded his grandfather’s work no more as ‘canonical’ but as a type of hortatory introduction to a life according to the ‘law, the prophets, and the other books’. He also emphasizes the difference between the original Hebrew and the Greek text and the difficulty of the translation. In his opinion, the pious Jewish lifestyle was apparently no longer to be taken for granted in Jewish Alexandria; therefore he feels the effort of translating the work is necessary. A review of the work, and especially of the writings employed in the Praise of the Fathers in Sirach 44:1–50:24, demonstrates that the grandfather knew or cited all the books of the Hebrew canon except Ruth, Canticles, Esther and Daniel. He could not have known Daniel, because it came into existence only later. Sirach 38:34c–39:1, the self-portrait of the scholar Ben Sirach, already essentially anticipates the division in the prologue: … he who devotes himself to the study of the law of the Most High will seek out the wisdom of all the ancients, and will be concerned with prophecies; he will preserve the discourse of notable men and penetrate the subtleties of parables; he will seek out the hidden meanings of proverbs … [This is followed in 39:6 by mention of] ‘words of wisdom’ and ‘thanksgiving to the Lord in prayer’. This statement distinguishes between law, prophets, historical narrative, wisdom books and hymnic poetry. Thus grandfather and grandson already tell us relatively much about the formation of the ‘Holy Scriptures’ in the motherland during the second century, but nothing about what was recognized as ‘canonical’ in Alexandria. Instead, the Jews in the Diaspora required special instruction on this point. The ‘prophets’ in the prologue may—as occurred later in the Hebrew canon—encompass both historical and prophetic books in the sense of the נביאים הראשונים or האחרונים, respectively. References to the ‘others that followed’—’other fathers’ or ‘other books’ respectively—betray an uncertainty that makes it clear that this collection of documents was by no means definitely delimited even in the grandson’s time." (The Septuagint as Christian scripture: its prehistory and the problem of its canon, M. Hengel, R. Deines, M. E Biddle, p96, 2002 AD)

5. 130 BC: Letter of Aristeas 155 quotes Job 42:3 from the LXX.

a. "For who is the one hiding his counsel from you, and, holding back, also thinks to hide his words from you, and who shall declare to me what I did not know, great and wondrous things, to which I did not pay attention?" (Job 42:3, LXX)

b. "‘Who is this that hides counsel without knowledge?’ “Therefore I have declared that which I did not understand, Things too wonderful for me, which I did not know.”" (Job 42:3, NASB)

c. “Thou shalt surely remember the Lord that wrought in thee those great and wonderful things”. For when they are properly conceived, they are manifestly great and glorious” (Letter of Aristeas 155, 130 BC)

d. “Vatic̣an Library, Gk. 1238. This is a vellum MS. in three volumes of the LXX belonging to the thirteenth century. On the close of the LXX follows the Testament of Job, folios 340a–349b, and on 350–380 of our present text [of Pseudo-Aristeas]. There are from 33–39 lines in each page. Strangely enough, above the general title of the Testaments, Διαθῆκαι τῶν ιβ πατριαρχῶν υἱῶν Ἰακώβ, appear the words Λεπτῆς Γενέσεως, which is one of the titles of the Book of Jubilees. That there was a close relation between these books we know independently.” (Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, R. H. Charles, Letter of Aristeas, Vol2, p284, 1913 AD)

e. “He said that he had heard from Theopompus that he had been driven out of his mind for more than thirty days because he intended to insert in his history some of the incidents from the earlier and somewhat unreliable translations of the law. When he had recovered a little, he besought God to make it clear to him why the misfortune had befallen him.” (Pseudo-Aristeas 314)

f. “Great and awe-inspiring are your works, Lord God Almighty. “Great” and “awe-inspiring” traditionally described God and his acts of creation and deliverance (Jdt 16:13; Dan 9:4; Job 42:3 LXX; Ep. Arist. 155; Tob 12:22; Sir 43:29; Pss 111:2–4; 139:14).” (AYBC, C. R. Koester, Revelation 15:3, 2014 AD)

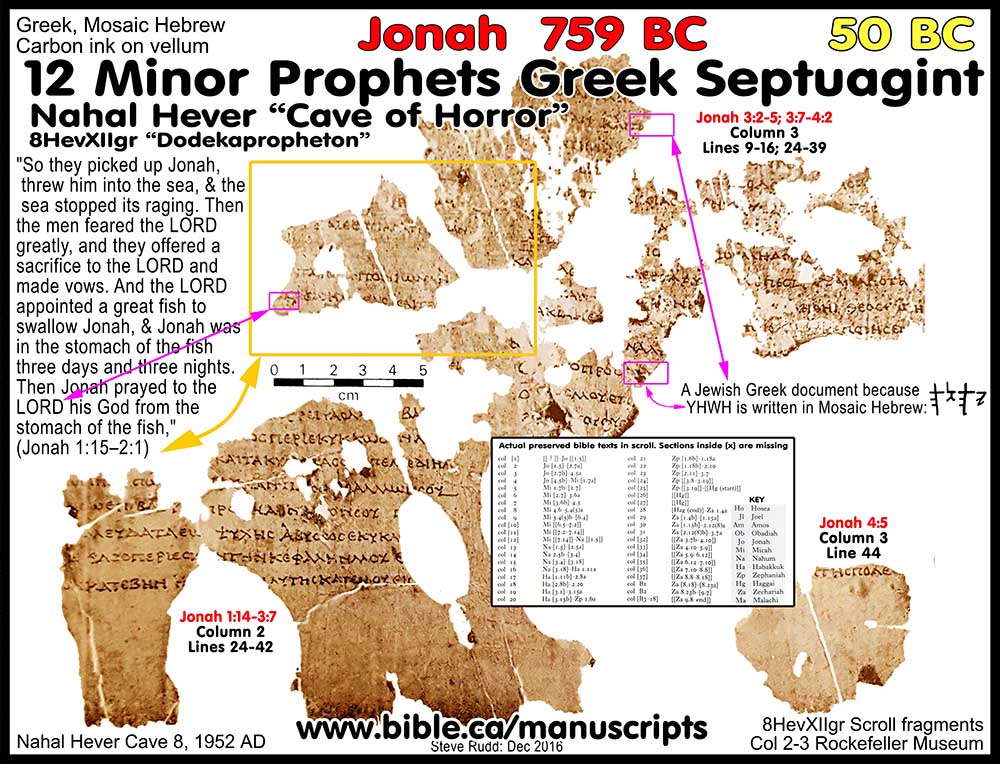

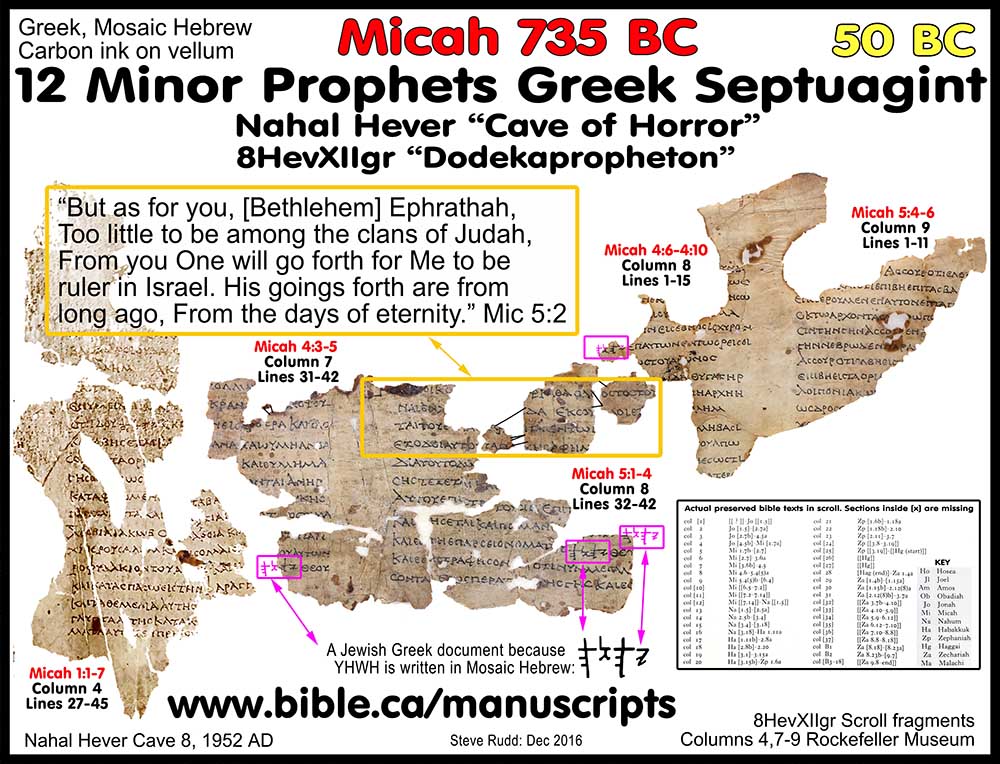

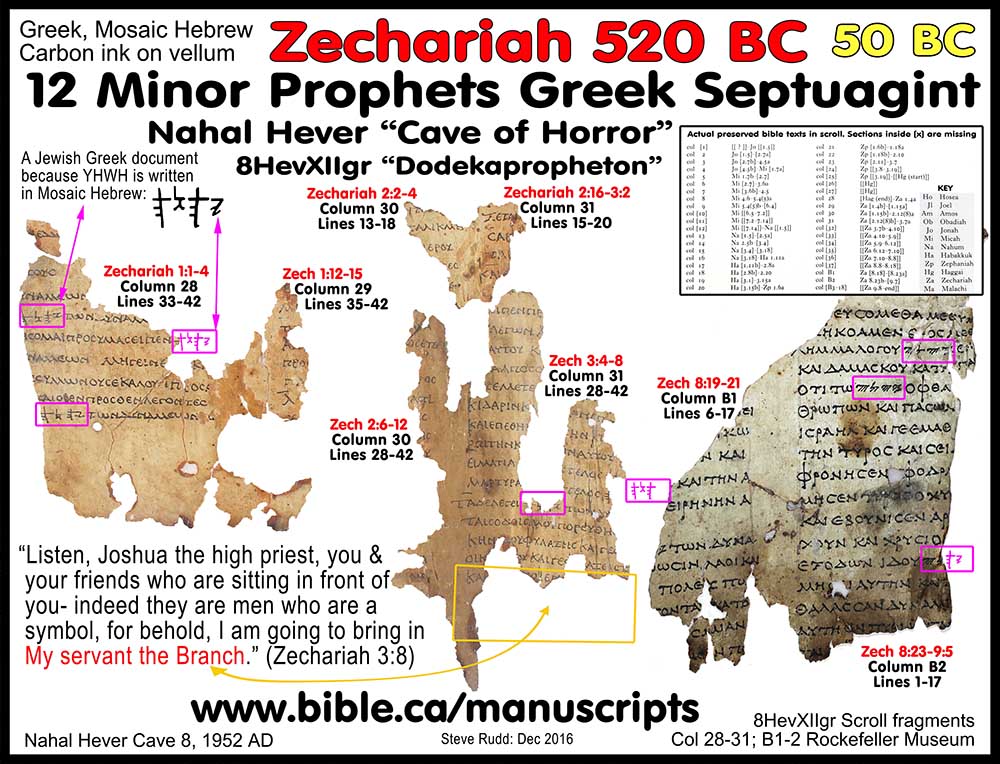

6. 50 BC: The Nahal Hever Greek scroll of the 12 minor prophets is a Jewish translation in 50 BC:

a. Greek Manuscript 8HevXIIgr (ie. Dodekapropheton) dates to 50 BC and cannot be a Christian manuscript.

b. The Greek scripture scroll (cave 8) is the longest scroll ever found in Israel at 32 feet long and are currently housed in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem.

c. The name of the God (YHWH) is written in paleo-Hebrew letters. Of special importance is the Greek Minor prophets scroll found at Nahal Hever (8HevXIIgr) because here, the Jews inserted Paleo-Hebrew into the Greek text out of respect for the name of God: YHWH. Christians simply would never do this, proving the Greek minor prophets scroll was a Jewish Greek translation long before Christ was born.

d. This scroll was corrected by Jewish scribes to make it agree with the Hebrew manuscript of the day. The book order and text closely follows the Masoretic. If this was a Christian production in 300 AD, a different book order would have been used.

e. It was among the possessions of the forty Bar Kokhba refugees who died in in 135 AD inside the Nahal Hever “Cave of Horror” near En Gedi. The fact the scroll was found among rebel Bar Kochba Jews as late as 135 AD proves it was a trusted text among the most pious Jews of the first century.

f. See full outline on the Jewish translated Greek Septuagint scroll of the 12 minor prophets.

|

“Jesus born in Bethlehem” |

“Jesus the Branch” |

7. 50 BC: Jewish apocalyptic documents translated into Greek:

a. “At the same time, we should not overlook the fact that an entire series of apocalyptic documents (not to mention the Qumran documents) originated in precisely the period that interests us, from the third century bce to the second century ce. A significant portion of them were translated into Greek: besides the five-part Enoch collection, the Assumption of Moses, the Apocalypse of Abraham, the Paralipomena Jeremiae, the Testament of Levi, the Syriac Baruch Apocalypse and 4 Ezra, to mention only a selection. Additional texts such as the Testament of Abraham, the Greek Baruch Apocalypse and the Coptic Zephaniah Apocalypse, the Slavonic Enoch, and the Jewish Sibyllines were probably written in the Diaspora. I limit myself here to the best-known titles." (The Septuagint as Christian scripture : its prehistory and the problem of its canon, M. Hengel, R. Deines, M. E Biddle, p95, 2002 AD)

8. 50 BC: Greek fragment of “Epistle of Jeremiah” discovered at Qumran (Dead Sea Scrolls): 7Q2-Greek LXX

a. The Epistle of Jeremiah is NOT the same as the book of Jeremiah the prophet.

b. “JEREMIAH, LETTER OF. This diatribe against idolatry originated during the Hellenistic era (332–63 bce). The apparent reference to the letter by the author of 2 Maccabees suggests a date prior to 150 bce (2 Macc 2:1–3). A very fragmentary copy of vv. 43–44, dating to about 100 bce, was discovered in Cave 7 at Qumran (7Q2). ( The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Volume 3, Page 235)

c. “7Q2 has been identified as Epistle of Jeremiah 43–44.” (Dictionary of New Testament Background, Cave 7 Fragments, Qumran, p196, 2000 AD)

d. “Some of the manuscripts written during the early Hasmonean period (130-ca. 63 B.C.E.), consisting at least in part of pre-Qumranic components: 7Q2 (Epistle of Jer.)” (The Encyclopaedia of Judaism, Qumran, vol 1, p 168, 2000 AD)

e. "However, Qumran has come to increase this stock with new [Greek] fragments from the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy and the Letter of Jeremiah [Greek-LXX], from Caves 4 and 7." (The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, Marcos, N. Fernández, p71, 2000 AD)

f. Outside the Pentateuch, two other manuscripts of the LXX were found, i.e. fragments of the Letter of Jeremiah 43–44 in 7Q2 (= Rahlfs 804), both dated around 50 bce, and the scroll of the Twelve Minor Prophets (8ḤevXIIgr = Rahlfs 943), which D. Barthélemy identified and studied, and which was recently edited by E. Tov in the series Discoveries in the Judaean Desert. According to experts in papyrology, it is to be dated between 50 bce and 50 ce, more probably towards the end of the 1st century bce." (The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, Marcos, N. Fernández, p191, 2000 AD)

9. 50 BC: Hebrew manuscript of the shorter version of Jeremiah the prophet found at Qumran:

a. In Cave 4 at Qumran 4QJera and 4QJerb are two Dead Sea manuscripts both written in Hebrew

b. The Hebrew fragment 4QJera follows the Hebrew Masoretic text.

c. The Hebrew fragment 4QJerb follows the shorter version of Jeremiah found in the Greek LXX.

d. This proves that the shorter Septuagint version of Jeremiah was indeed translated from a Jewish Hebrew text in 50 BC.

10. 30 AD: Philo of Alexandria quotes extensively from almost every book of the Septuagint including Isaiah!

a. The fact that Philo never mentions Jesus actually strengthens the text is Jewish and that Christians never tampered with or corrupted it centuries later!

b. Philo quotes from the Greek Isaiah!

i. Philo QG II 43 quotes Isa 1:9 LXX

ii. Philo On Dreams 2.172 quotes Isa 5:7 LXX

iii. Philo QG I 100 quotes Isa 8 LXX

iv. Philo Names 169 quotes Isa 48:22 LXX

v. Philo Rewards 158 quotes Isa 54:1 LXX

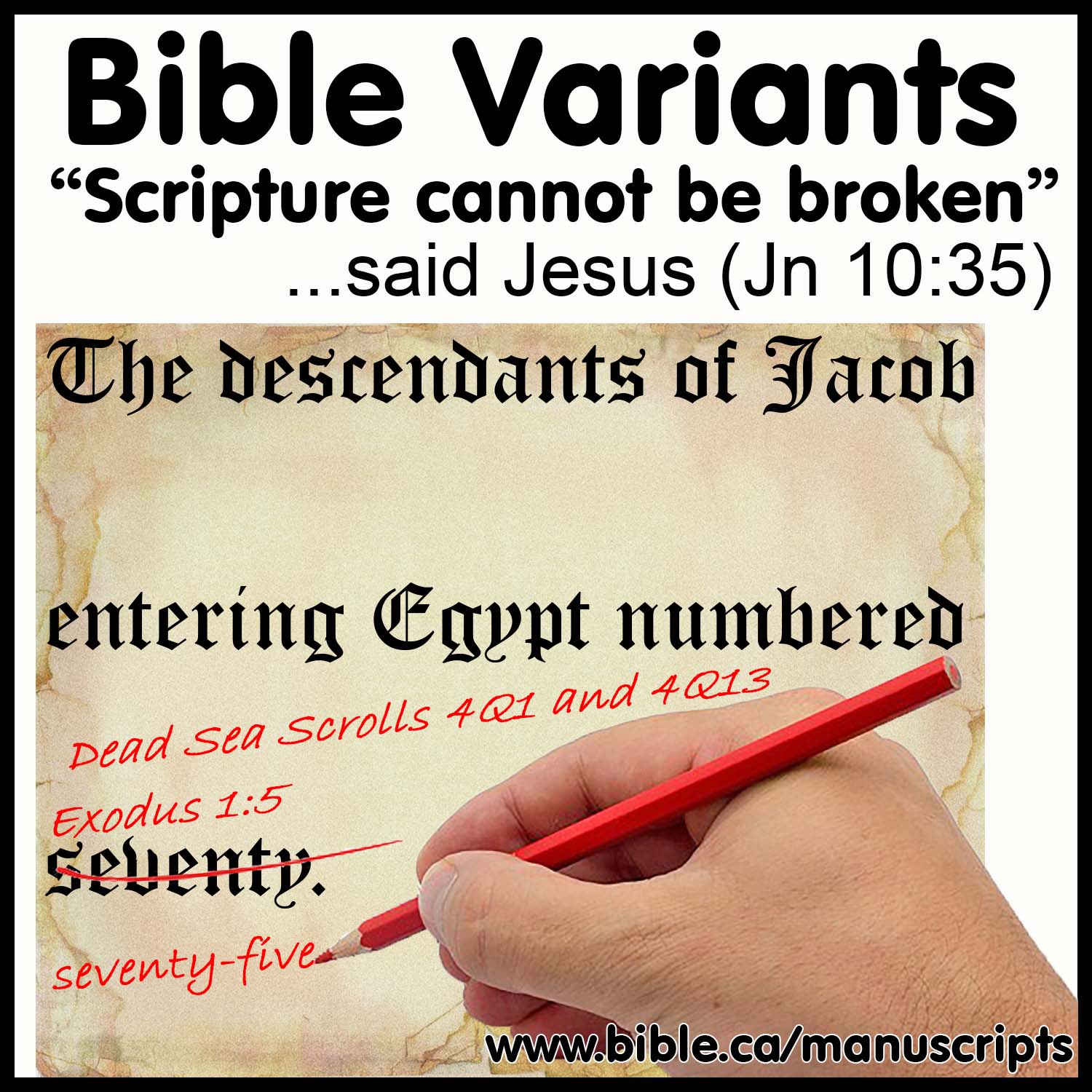

c. Philo copies the Septuagint’s number of 75 for the number who entered Egypt in contradiction to the Masoretic Hebrew text that says 70: “all the souls which came out of Jacob were seventy and five” (Philo, On the Migration of Abraham 199, 30 AD)

d. Philo copies the longer Septuagint chronological numbers in Genesis: Philo QG I 82-83; QG II 17

i. He also mentions Enoch’s numbers 165, 200, 365 in Philo QG I 82-83 and Noah’s age of 600 at the Flood in Philo QG II 17.

ii. Philo Philo’s numbers for Enoch are the LXX’s. (The MT’s are 65, 300, 365).

e. “For the first century a.d. we have the very important evidence of Philo, who uses the lxx. and quotes largely from many of the books. There are indeed some books of the Hebrew canon to which he does not seem to refer, i.e. Ruth, Ecclesiastes, Canticles, Esther, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel. But, as Professor Ryle points out, “it may be safely assumed that Ruth and Lamentations were, in Philo’s time, already united to Judges and Jeremiah in the Greek Scriptures”; and Ezekiel, as one of the greater Prophets, had assuredly found its way to Alexandria before a.d. 1." (An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, H. B. Swete, p24, 1914 AD)

f. Here are the books Philo May Not have quoted the Septuagint on: Ruth, Ecclesiastes, Canticles, Esther, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel. All the rest he did!!!

g. Finally, it is important to note that Philo lived in the epicenter of Greek culture at Alexandria. Obviously the Septuagint Tanakh was his default Bible.

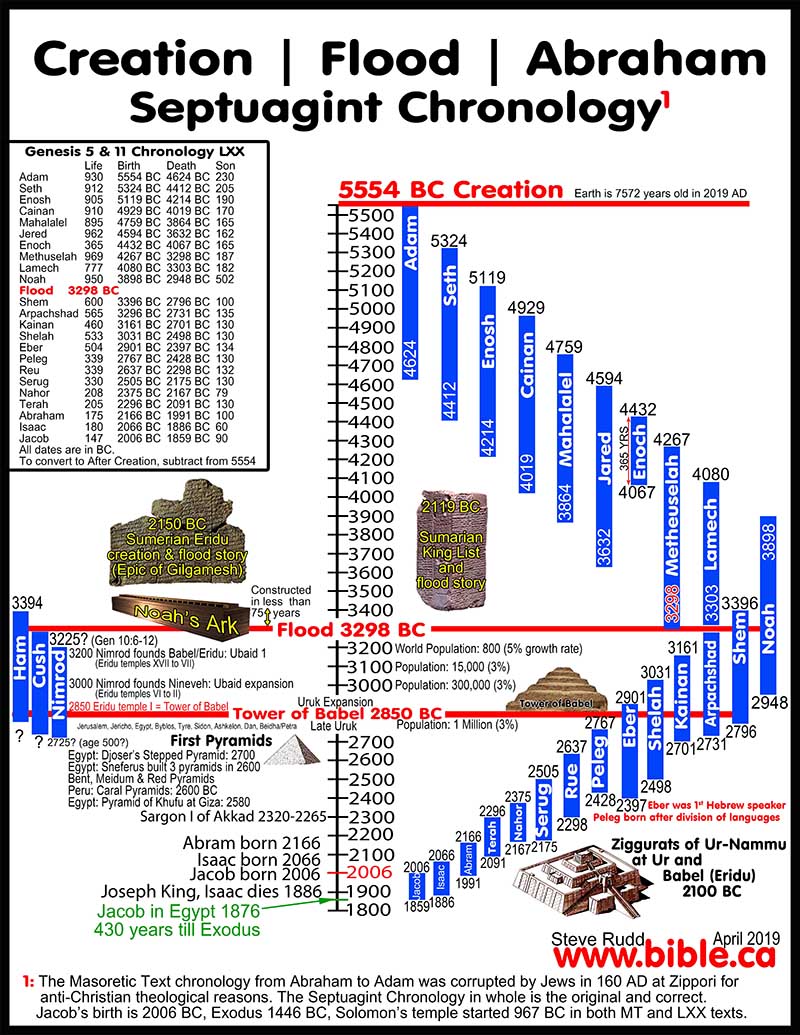

11. Josephus (like Philo) copied the longer chronological numbers of Gen 5&11 from the Septuagint.

a. Josephus mentions Jesus and his brother James: “Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the Sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others, [or, some of his companions]; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned.” (Josephus, Antiquities 20.200, 70 AD)

b. The longer Genesis Chronology found in Josephus Antiquities 1.83–87, 149–50

c. Josephus Against Apion 1.1 says Bible history spans 5000 years: “Those antiquities contain the history of 5,000 years; and are taken out of our sacred books, but translated by me into the Greek tongue”. This again validates the longer chronology found in Septuagint in opposition to the Hebrew Masoretic text.

II. Witness of world’s leading Septuagint scholars:

1. “The LXX translation of the Prophets was done sometime between 250 and 150 b.c.” (ABD, Jeremiah)

2. “The most important reason for studying the LXX then is to read and understand the thought of Jews in the pre-Christian centuries.” (ABD, Septuagtint)

3. "It is generally agreed that the Pentateuch or Torah was translated from its Hebrew original into Greek during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 b.c.), possibly around 280, according to reliable patristic testimony. The books in the Prophets and Writings were translated later, probably all of them by about 130 b.c. as suggested by the Greek Prologue to Ben Sira." (The Septuagint and the Text of the Old Testament, P. J. Gentry, Bulletin for Biblical Research, Vol. 16, p 193, 2006 AD)

4. "The most securely dated portion of the LXX is the Pentateuch or Torah (including Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), which was translated into Greek during the early to mid third century b.c. This dating is well attested by the mid to late-second century b.c. Letter of Aristeas, which describes how the translation was undertaken in Alexandria (Egypt) during the reign of King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 b.c.) and also by several other second- and third-century b.c. texts that reference the Greek Pentateuch. The dating of the other books is less certain but the scholarly consensus is that the LXX was completed by the end of the first century b.c., although it has been argued that Baruch and 3–4 Maccabees were written in the first century a.d. and incorporated into the LXX shortly thereafter.17 The prologue to the book of Sirach (or Ecclesiasticus), which was written in the late second century b.c. by the grandson of Jesus Ben Sirach, implies that in his time there were already Greek translations for “the law itself, and the prophets, and the rest of the books,” and so it seems that the LXX was largely completed by this early date. The LXX is, thus, very much a product of the Hellenistic age. It is possible, of course, that the codices of the fourth and fifth centuries a.d. incorporate some post-Hellenistic modifications affecting the gemstones named, but at present there is no reason to think this happened." (Old Testament Gemstones: A Philological, Geological, and Archaeological Assessment of the Septuagint, J. A. Harrell, Bulletin for Biblical Research, 21:1–4, p145, 2011 AD)

5. "Apparently, even Paul utilized a revised text for Isaiah, Job and 1 and 2 Kings, i.e. for relatively freely translated Old Testament texts. I have already said that it is entirely possible that Paul himself took up recensional alterations in the text since, as a Pharisee and scholar who had studied in Jerusalem, he knew the original. After the building of the Herodian temple, Jerusalem became even more than previously the religious centre of world Judaism. The Pharisees, the most influential religious party in Palestine, must have had a particular interest that the form of the text they had established should also gain entry into the Diaspora synagogues and that its gradually forming canon should prevail there too. An example of this influence is the first reference to this very ‘canon’ of twenty-two writings in Josephus (Ap 1:37–42). (The Septuagint as Christian scripture : its prehistory and the problem of its canon, M. Hengel, R. Deines, M. E Biddle, p88, 2002 AD)

6. "Date: According to the generally accepted explanation of the testimony of the Epistle of Aristeas, the Torah translation was carried out in Egypt in the beginning of the third century BCE. This assumption is compatible with the early date of several Greek papyrus and leather fragments of the Torah from Qumran and Egypt, some of which date from the middle of the 3rd century until the 1st century BCE. The remaining Scripture books were translated at different times. Some evidence for their dates is external, e.g. quotations from Ǿ in ancient sources, and some internal, e.g. reflections of historical situations or events found in the translation. The post-Pentateuchal books were translated after the translation of the Torah, for most of these translations use its vocabulary, and several translations also quote from the Greek Torah. Since the Prophets and several of the Hagiographa were known in their Greek version to the grandson of Ben Sira at the end of the 2nd century BCE, we may infer that most of them were translated in the beginning of that century or somewhat earlier. There is only limited explicit evidence concerning the dates of individual books: Chronicles is quoted by Eupolemos in the middle of the 2nd century BCE, and Job by Pseudo-Aristeas in the beginning of the 1st century BCE. Swete*, 25-6. The translation of Isaiah contains allusions to historical situations and events that point to the years 170-150 BCE" (Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, Emanuel Tov, p131, 2012 AD)

7. "Until the second century AD, the Jews universally regarded the Greek translation of the OT as a faithful interpretation of the original Hebrew. Philo and Josephus lauded the Greek version, the Sanhedrin authorized it to be read in the Greek-speaking synagogues, and the apostles quoted from it freely. Russell notes that "before the second century of the Christian religion, no traces can be found of any controversy as to the differences supposed to exist in the Greek and Hebrew texts of the sacred books" (216, n. 129). The unanimous Jewish approval of the LXX during the first four centuries of its existence can only be explained if it was a generally accurate translation of the Hebrew text in circulation during that time. What happened in the second century? The Palestinian Jews suddenly began repudiating the original translation of the Greek OT and replacing it with new translations (by Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion). We shall explore the reasons for this presently." (Primeval Chronology Restored: Revisiting the Genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11, Jeremy Sexton, Henry B. Smith Jr. Bible and Spade, 29, no. 2, p 45, 2016 AD)

8. "With regard to the Hagiographa [The books of the Hagiographa are: Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations, Daniel, Esther, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles], in some cases we have data which lead to a more definite conclusion. Eupolemus, who, if identical with the person of that name mentioned in 1 Macc. 8:17, wrote about the middle of the second century, makes use of the Greek Chronicles, as Freudenthal has clearly shewn. Ezra-Nehemiah, originally continuous with Chronicles, was probably translated at the same time as that book. Aristeas (not the pseudonymous author of the letter, but the writer of a treatise περὶ Ἰουδαίων) quotes the book of Job according to the lxx., and has been suspected of being the author of the remarkable codicil attached to it (Job 42:17 b–e). The footnote to the Greek Esther, which states that that book was brought to Egypt in the 4th year of “Ptolemy and Cleopatra” (probably i.e. of Ptolemy Philometor), may have been written with the purpose of giving Palestinian sanction to the Greek version of that book; but it vouches for the fact that the version was in circulation before the end of the second century b.c. The Psalter of the lxx. appears to be quoted in 1 Macc. 7:17 (Ps. 78 = 79:2), and the Greek version of 1 Maccabees probably belongs to the first century b.c. … For the first century a.d. we have the very important evidence of Philo, who uses the lxx. and quotes largely from many of the books. There are indeed some books of the Hebrew canon to which he does not seem to refer, i.e. Ruth, Ecclesiastes, Canticles, Esther, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel. But, as Professor Ryle points out, “it may be safely assumed that Ruth and Lamentations were, in Philo’s time, already united to Judges and Jeremiah in the Greek Scriptures”; and Ezekiel, as one of the greater Prophets, had assuredly found its way to Alexandria before a.d. 1." (An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, H. B. Swete, p24, 1914 AD)

9. "Most scholars, while rejecting many of the details in the Letter of Aristeas as legendary, would agree that the Pentateuch was translated in Egypt around 250 b.c. Manuscripts that date to within one hundred years of the original translation are now extant. It is generally conceded that the rest of the Old Testament was translated into Greek by 100 b.c. at the latest. However, there is some debate as to whether these books were also translated in Egypt. Because of the work of scholars such as Albright who have shown strong Egyptian influences in the Hebrew underlying the Septuagint of the Pentateuch, it has sometimes been assumed that all the Old Testament was translated in Egypt. Bickerman has pointed to the fact that most manuscripts of the Book of Esther contain a colophon which states that the book was translated in Jerusalem. Both Tov and Barthélemy have argued for the Palestinian translation of some other books. At this time, however, not enough data is available to draw any definite conclusions about this matter. (The Transmission-History of the Septuagint. W. W. Combs, Bibliotheca Sacra, 146, p262, 1989 AD)

10. "We can see that Hellenistic Judaism had a relatively well defined canon of ‘Holy Scripture’ already in the second century bc, which thus preceded the witnesses of the New Testament writings; in the definition of what was to be regarded as ‘canonical’ the foundation is being laid for the later differentiation between ‘canonical’ and ‘apocryphal’. I see evidence for this position in the prologue of Jesus ben Sirach from the second half of the second pre-Christian century: he assumes as canonical Scripture not only the three divisions transmitted by the Masoretes comprising the νόμος (the תורה), the προφῆται (the נביאים) and the ἄλλα πάτρια βιβλία (10; cf. 1) or the λοιπά τῶν βιβλίων (25; the כתובים), which, including the already composed Dodekapropheton [ie. the 12 prophets] (49:10), were available to the grandson and translator in the Praise of the Fathers in his grandfather’s book of proverbs (Chap. 44–50). He also distinguishes this literature from the one based on it as commentary, beginning with the work of his grandfather, because of the ἀναγνωσις and the resulting ἱκανὴ ἕξις (10–12). He repeats the same distinction in reference to the problem of translation by basing his excuse for the obscurity of his own translation (οὐ γὰρ ἰσοδυναμεῖ αὐτὰ ἐν ἑαυτοῖς Ἑβραϊστὶ λεγόμενα καὶ ὅταν μεταχθῇ εἰς ἑτέραν γλῶσσαν, 22) on the fact that ‘even the law, the prophets, and the other books read in the original (ἐν ἑαυτοῖς λεγόμενα) manifest a significant difference (οὐ μικρὰν ἔχει τὴν διαφοράν, 26)’ when compared with the translation. It seems to me justifiable to conclude that the distinction—in relation both to their character and the quality of their translation—between Law, Prophets and the other Writings, on the one hand, and the literature first exemplified in the work of his grandfather, on the other, was grounded first and foremost in the distinction between ‘canonical’ and ‘apocryphal’ already current at the time. It can therefore be assumed that a differentiation within, ‘Holy Scripture’ as a whole was already existing in Judaism. I believe that the primitive Christian witnesses attest this differentiation as a ‘given’: the Palestinian canon in the form preserved in the Masoretic tradition was seen as authentic canon, the other writings transmitted in the Alexandrian canon—both those translated from Hebrew or Aramaic and those originally written in Greek—as ‘apocryphal’. It may seem like an over-statement to use this terminology in relation to this period, although sufficient examples illustrate that external categories may be more appropriate for characterizing a period than those already known. But this distinction brings one close—as early as the pre-Christian era of Judaism—to the solution of a problem that will be significant for the problem of the Christian canon. The content of the Alexandrian LXX canon, which does not meet the canonical standard transmitted in Josephus (c. Ap I 36–42) according to which the succession of the prophets, determinative of canonicity, ended in the time of Artaxerxes I or Ezra and Nehemiah—the description of the Seleucid religious persecution in 1 and 2 Maccabees, Jesus ben Sirach’s mention of the high priest Simon—would have been, from the outset, not only appended to, but considered inferior in terms of authority to the Scriptures of the Palestinian canon. The only question that remains open is whether this distinction was a phenomenon common to Palestinian and Hellenistic Judaism or a point of contention between the two communities: to my knowledge, there are no pre-Christian sources useful in answering that question." (The Septuagint as Christian scripture : its prehistory and the problem of its canon, M. Hengel, R. Deines, M. E Biddle, p2, 2002 AD)

11. "the translation of Isaiah is more context-related. It is to be dated—with Seeligmann—to the early Maccabean period, i.e. in the middle of the second century, after the Jewish high priest Onias IV founded the temple at Leontopolis (c. 160) and also strengthened the political self-consciousness of Jews in Egypt; at a few points the Ptolemaic-Egyptian milieu and the historical situation of its origin becomes evident (cf. Isa. 19:18–21). According to more recent studies, allusions are made even to the Roman conquest of Carthage and the Parthian conquest of Babylon (146 and 141 bce; respectively) It already presumes the translation of the Psalms, the Minor Prophets and Ezekiel.28 A little later, the Judaeo-Palestinian historian Eupolemos seems to have utilized Chronicles in Greek translation for his work. The possibility cannot he excluded that the Isaiah-LXX involves an updating revision of an older translation. I consider it unlikely that the most important prophetic book would be translated so late. The prologue of Sirach, 2 Maccabees 2:13 and the colophon of Esther demonstrate that the very period, during and after the Maccabean revolt, that led indirectly to a strengthening of Jewry in Egypt, was an epoch of intensive translation activity into Greek, not only in Egypt, but also in the motherland. One can well understand the complaint of the grandson and translator of Ben Sirach in his prologue about the difficulty of such translation from Hebrew into Greek. But apparently in this period many Jews did not flinch from this labour. This series of new translations, which created an entirely new literary corpus, was an intellectual accomplishment of the first order. As indicated by the fragments preserved in Alexander Polyhistor, this translation process was paralleled by a vital literary productivity dependent on the LXX, in original Greek and in Greek literary forms. (The Septuagint as Christian scripture : its prehistory and the problem of its canon, M. Hengel, R. Deines, M. E Biddle, p85, 2002 AD)

12. "From among the most significant exceptions must be noted Pap. Gr. 458 of the John Rylands Library (= Rahlfs 957), from the 2nd century bce, the oldest known fragment of the LXX: it contains fragments of Dt. 23–28. Papyrus Fouad Inv Nr 266 (= Rahlfs 848), dated around 50 bce and with the Tetragrammaton written in square Hebrew letters: it contains fragments from Deuteronomy 17–33. The Septuagintal manuscripts of the Pentateuch identified in Caves 4 and 7 in Qumran are pap7QLXXEx (= Rahlfs 805); 4QLXXLeva (= Rahlfs 801); pap4QLXXLevb (= Rahlfs 802); 4QLXXNum (= Rahlfs 803) and 4QLXXDeut (= Rahlfs 819). The fragments of Leviticus 2–5 found in 4QLXXLevb, from the 1st century bce are written in a script related to the script of papyrus Fouad 266, with the Tetragrammaton written in Greek (ἰάω) instead of a simple transcription or the translation κύριος. Outside the Pentateuch, two other manuscripts of the LXX were found, i.e. fragments of the Letter of Jeremiah 43–44 in 7Q2 (= Rahlfs 804), both dated around 50 bce, and the scroll of the Twelve Minor Prophets (8ḤevXIIgr = Rahlfs 943), which D. Barthélemy identified and studied, and which was recently edited by E. Tov in the series Discoveries in the Judaean Desert. According to experts in papyrology, it is to be dated between 50 bce and 50 ce, more probably towards the end of the 1st century bce." (The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, Marcos, N. Fernández, p191, 2000 AD)

III. The Divine name YHWH in ancient Greek and Hebrew manuscripts:

2. One of the ways you can prove the Greek Tanakh (Septuagint) was a product of Jews, is the high respect they places upon the name of God: YHWH.

a. We know that when Jew calls upon the name of YHWH alone, he will be cast into hell for unbelief in Jesus Christ their risen messiah: "And there is salvation in no one else; for there is no other name under heaven that has been given among men by which we must be saved.” (Acts 4:12)

b. Christians recognized the name Jesus replaced YHWH as the name of God because Jesus, being creator, is both YHWH and Jesus the Nazarene (ie branch of David)

c. The Holy Spirit chose in the New Testament to universally translate the Hebrew YHWH as Greek “KURIOS” (Lord)

3. Nomina sacra: “Sacred Names”

a. Jews around 100 BC began to practice “Nomina sacra” where they would use substitutions for the name of God YHWH.

b. Christians also practiced this in a wide range of words in the Byzantine era including: God, Lord, Jesus, Christ/Messiah, Son, Spirit/Ghost, David, Cross/Stake, Mother, God Bearer/Mother of God, Father, Israel, Savior, Human being/Man, Jerusalem, Heaven/Heavens

c. Of special importance is the Greek Minor prophets scroll found at Nahal Hever (8HevXIIgr) because here, the Jews inserted Paleo-Hebrew into the Greek text out of respect for the name of God: YHWH. Christians simply would never do this, proving the Greek minor prophets scroll was a Jewish Greek translation long before Christ was born.

4. YHWH in ancient Greek manuscripts: Qum’ran, Masada, Nahal Hever

a. YHWH written in Aramaic Hebrew in Papyrus Fouad 266

b. YHWH written in Paleo-Hebrew in Greek Minor prophets scroll: 8HevXIIgr (Nahal Hever)

c. YHWH transliterated as ΙΑΩ (4QLXXLevb, Qumran)

d. YHWH represented as ΠΙΠΙ

e. YHWH translated or written as κύριος ie. Kurios = Lord (Pap. Oxyr. 656)

5. YHWH in ancient Hebrew manuscripts from Qum’ran, Masada and Nahal Hever:

a. YHWH written in Aramaic Hebrew

b. YHWH written in Mosaic Hebrew

c. YHWH represented by four dots

d. YHWH in Aramaic script glossed by “adonay” [Greek: Lord]

IV. Rabbi Tovia Singer bears false witness to his own Jewish history regarding the Septuagint:

- Jewish Fiction writer Rabbi Tovia Singer says that none of the Old Testament books, except the five books of Moses, were translated into Greek until after 200-400 AD. His point that only the Torah was initially translated in 282 BC in Alexandria is accepted by everyone and therefore irrelevant to the real discussion that the rest of the books of the Old Testament (Joshua – Malachi) were translated into Greek and in full circulation long before the birth of Christ:

- "The original Septuagint was a Greek translation of only the Torah (the five books of Moses) nothing else. Therefore the book of Isaiah was not even part of the Septuagint translated by learned Jews thousands of years ago, as [Christian] missionaries routinely claim. Rather the book of the Tanach is a part of the Prophets, the second section of Jewish scriptures, and was forged by the church many centuries later. … The first century Roman historian Josephus Flavius, similarly states that under Ptolemy Philadephius, only the Law was translated" (Let's Get Biblical, Tovia Singer, Missionaries Defends Matthew by citing the Septuagint., vol 1, p49, 2014 AD)

- "The Septuagint in our hands is not a Jewish document, but rather a Christian recension. The original Septuagint, translated some 2,200 years ago by 72 Jewish scholars, was a Greek translation of the Five Books of Moses alone, and is no longer in our hands. It therefore did not contain the Books of the Prophets or Writings of the Hebrew Bible such as Isaiah, from which you asserted Matthew quoted. The Septuagint as we have it today, which includes the Prophets and Writings as well, is a product of the Church, not the Jewish people. … Christians such as Origin and Lucian (third and fourth century C.E.) edited and shaped the Septuagint that missionaries use to advance their untenable arguments against Judaism. In essence, the present Septuagint is largely a post-second century Christian translation of the Bible, used zealously by the Church throughout its history as an indispensable apologetic instrument to defend and sustain Christological alterations of the Jewish Scriptures… Accordingly, the Jewish people never use the Septuagint in their worship or religious studies because it is recognized as a corrupt text." (Let's Get Biblical, Tovia Singer, The Virgin Birth: A Christian Defends Matthew by Insisting That the Author of the First Gospel Relied on the Septuagint When He Quoted Isaiah to Support the Virgin Birth, vol 2, p52, 2014 AD)

- Summary of Rabbi Tovia Singer historical lies:

- Tovia Singer Historical lie #1: Rabbi Tovia Singer teaches that none of the Old Testament books (except for Gen-Deut) were translated into Greek during the ministry of Jesus the Nazarene (lit: Jesus the branch) or the church.

- Tovia Singer Historical lie #2: Rabbi Tovia Singer teaches that the first Greek translations of Tanakh (except the Torah) were made by Christians after 200 AD, not by Jews in 150 BC.

- Tovia Singer Historical lie #3: Rabbi Tovia Singer teaches that Christians corrupted the Septuagint in order to convert Jews. For example the word “virgin” did not exist in Isa 7:14 during the first century AD, but was invented after 100 AD to convince Jews that Jesus was born of a Virgin and correct the blunder of Matthew who mistakenly recorded the word as “virgin”.

- Tovia Singer Historical lie #4: Rabbi Tovia Singer teaches that Jews NEVER translated the entire Tanakh from Joshua to Malachi into Greek.

- Tovia Singer Historical lie #5: Rabbi Tovia Singer teaches that the 39 books of the Tanakh Septuagint is a product of the Byzantine church, not Jews.

- REFUTATION OF the historical lies of Rabbi Tovia Singer about the Septuagint:

- There is not a recognized Septuagint scholar (including Jewish Scholars) who agrees with Tobia Singer’s fictions about the LXX. The leading Septuagint scholar in the world IS JEWISH Emanuel Tov and he plainly states the LXX is a Jewish document from the Hellenistic era long before Christ was born.

- "Until the second century AD, the Jews universally regarded the Greek translation of the OT as a faithful interpretation of the original Hebrew. Philo and Josephus lauded the Greek version, the Sanhedrin authorized it to be read in the Greek-speaking synagogues, and the apostles quoted from it freely. Russell notes that "before the second century of the Christian religion, no traces can be found of any controversy as to the differences supposed to exist in the Greek and Hebrew texts of the sacred books" (216, n. 129). The unanimous Jewish approval of the LXX during the first four centuries of its existence can only be explained if it was a generally accurate translation of the Hebrew text in circulation during that time. What happened in the second century? The Palestinian Jews suddenly began repudiating the original translation of the Greek OT and replacing it with new translations (by Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion). We shall explore the reasons for this presently." (Primeval Chronology Restored: Revisiting the Genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11, Jeremy Sexton, Henry B. Smith Jr. Bible and Spade, 29, no. 2, p 45, 2016 AD)

- We supply a single irrefutable archeological proof which exposes Jewish Anti-Christian Rabbi Tovia Singer for the “academic hack” he really is: See full outline on the Jewish translated Greek Septuagint scroll of the 12 minor prophets that dates to 50 BC.

- Jewish Rabbi Tovia Singer is an "anti-Christian missionary" who devotes much energy to trashing Christianity to an uninformed audience who mistake him for a credible and truthful historical scholar. In fact, almost everything he teaches about the history Christianity is just a continuation of the first Jewish lie, namely, that Jesus did not rise from the dead, but the disciples stole the body. Messianic prophecy found in the book of Isaiah is a huge problem for Singer, especially Isa 7:14 where the Septuagint uses the word "virgin". This is devastating to Tovia Singer, so he fabricated an historic lie that Isaiah did not exist until after “Christians translated it” after 300 AD and INSERTED the word virgin to support the narrative of Matthew. Tovia Singer, being a Jew, would be well advised that his fiction that a Greek Isaiah did not exist before the birth of Christ makes him as bad as "Madman Ahmadinejad" who "denies the holocaust, while preparing for the next", as Netanyahu said in his UN speech. The archeological and textual evidence that the entire old testament was translated into Greek long before Christ was born is as irrefutable and factual as the Holocaust of 135 AD under Hadrian and 1945 AD under Hitler.

- Jews attempted to alter the word Virgin in Isa 7:14, not Christians!

- “But here, too, you dare to distort the translation of this passage made by your elders at the court of Ptolemy, the Egyptian king, asserting that the real meaning of the Scriptures is not as they translated it, but should read, “Behold a young woman shall conceive,” as though something of extraordinary importance was signified by a woman conceiving after sexual intercourse, as all young women, except the barren, can do. And even the barren can become fertile by the power of God. Samuel’s mother, who had been sterile, gave birth to her child by the will of God. The same thing can be said of the wife of the holy Patriarch Abraham, and of Elizabeth, who bore John the Baptist, and of many other women You must realize, therefore, that nothing is impossible for God to do, if He wills it. And, especially when it was prophesied that this would happen, you should not venture to mutilate or misinterpret the prophecies, for in doing so you do no harm to God, but only to yourselves.’" (Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 84, 125 AD)

- In the end, Jewish Rabbi Tovia Singer knows it is game over for his ministry if, for example, “Virgin” was the translation by Jews in the Septuagint in 150 BC. This is why he has no choice but to fabricate and lie about the history of the Septuagint.

- Maybe Christians should start up a "Septuagint Memorial Museum" in Jerusalem to counter such Tovia Singer's lies so that "those who corrupt history will not be allowed to repeat it".

Conclusion:

1. There are at least 10 archeological proofs that all 39 books of the Old Testament were translated into Greek (Septuagint) before 150 BC as early as 250 BC.

a. While the word Septuagint was coined first by Augustine in 400 AD, the Septuagint was a Jewish translation in full circulation and in use in every synagogue in the world.

b. This explains why the rise of Christianity brought about massive conversions among the first century Jews.

2. When Jesus was born of a virgin, Matthew, for example, simply quoted one of the hundreds of Greek Isaiah scrolls laying on the Table of the Scrolls or laying in storage in the Ark of the Scrolls, in each of the hundreds of synagogues in Jerusalem.

a. See outline on Ark of Scrolls

b. See outline on Table

of Scrolls

3. God’s providence equipped early Christians with the three most important tools to convert Jews:

a. The Septuagint: A Jerusalem certified Hebrew Bible translated by Jews and in full circulation in thousands of synagogues hundreds of years before Jesus rose from the dead.

b. Synagogues (Proto-churches): Synagogues were “Proto-churches” in the waiting for Christians to arrive.

c. Weekly attendance: Neither Synagogues or weekly attendance are found in the Old Testament Tanakh but developed providentially and naturally as a result of the Greek Septuagint. While Mosaic Judaism only requires Jews to assemble 3 times a year, God foresaw weekly attendance would be mandatory in the church, and when Christianity arrived it was a “turn key” arrangement for conversion to Christianity.

d. The “Jewish

Christian Maker”: Jews called them Mikveh. Christians called them full

immersion water baptistries. Every synagogue had a “Jewish baptistry”. On the

day of Pentecost, the 3000 were baptized in the name of Jesus for the remission

of their sins IN SYNAGOGUE MIKVAOT.

|

The Septuagint LXX “Scripture Cannot Be Broken” |

|||||

|

Start Here: Master Introduction and Index |

|||||

|

Six Bible Manuscripts |

|||||

|

1446 BC Sinai Text (ST) |

1050 BC Samuel’s Text (SNT) |

623 BC Samaritan (SP) |

458 BC Ezra’s Text (XIV) |

282 BC Septuagint (LXX) |

160 AD Masoretic (MT) |

|

Research Tools |

|||||

|

Steve Rudd, November 2017 AD: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections |

|||||

By Steve Rudd: November 2017: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Go to: Main Bible Manuscripts Page