35 Jewish Elephantine Papyri Egypt, Jewish colony: 495 - 399 BC

The Jedaniah Archive

Quick links to three featured papyri:

General introduction (Founding of Elephantine, discovery of papyrus collection)

1. Four Papyrus: Temple of YHWH burned (Sanballat, Bagohi Governor of Judea)

a. #1: Temple destruction

b. #2: Water well stopped temple destroyed

c. #3: Bribe to rebuild temple

d. #4: Jerusalem allows temple rebuild

2. Document of wifehood (bride price, dowry, divorce causes and penalties)

3. Passover regulations (unleavened wine and bread)

Conclusion (Importance of Elephantine papyrus to the Bible)

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Archaeologists are digging up bible stories!!! |

||||

|

Archaeology is an important science that confirms the historical accuracy of the Bible. Since the Bible refers to hundreds of cities, kings, and places, we would expect to find evidence from on-site excavations. And this is exactly what we have found. The Bible is the most historically accurate book of history on earth. Read the Bible daily! |

|

|||

|

|

||||

1. See also:

a. General introduction (Founding of Elephantine, discovery of papyrus collection)

b. Temple of YHWH burned (Sanballat, Bagohi Governor of Judea)

c. Document of wifehood (bride price, dowry, divorce causes and penalties)

d. Passover regulations (unleavened wine and bread)

e. Conclusion (Importance of Elephantine papyrus to the Bible)

2. The

island of Elephantine may have got its name from the presence of large rocks

that have the appearance of elephants and/or because the border town was the

gateway to the ivory and elephant hide trade with Ethiopia.

a. "The island was named Elephantine in Greek, either because it was the center of the ivory trade between Egypt and Nubia or because it is surrounded by black rocks shaped like elephants." (Lexham Bible Dictionary, Elephantine, 2015 AD

b. "The Bible probably includes the twin cities of Elephantine and Syene in two occurrences of the phrase “from Migdol to Syene” (Ez 29:10; 30:6), that is, from Egypt’s northern border to its southern border. The city’s name was an Aramaic version of an Egyptian name meaning “city of ivories” and was translated into Greek as Elephantine. Because of its strategic importance on Egypt’s southern boundary with Nubia, it was probably fortified as early as the third dynasty (27th century bc) and figured repeatedly in Egypt’s military history. Elephantine was also a major commercial center. Since the first cataract was just upstream from Elephantine/ Syene, the twin towns were the terminal ports for deep water navigation. Both towns had wharves and were fortified with garrisons to protect the trade in ivory, animal skins, spices, minerals, slaves, and food. Also a religious center, Elephantine was the temple city of Khnum, the Egyptian god of the cataract region, who presided over the flood cycles of the Nile." (Tyndale Bible Dictionary, Elephantine Papyri, 2001 AD)

3. The island of Elephantine, beside the twin city of Aswan/Syene that is mentioned twice as the southern border of Egypt directly above the first cataract (rapids requiring portage):

a. "The southernmost city of Egypt, situated on an island in the River Nile. Recorded for the first time in the 3rd Dynasty, it was a military stronghold and trade center, the seat of the royal officials responsible for the trade with Nubia (Ethiopia), whose most important export was ivory. The name of the city probably reflects this trade." (The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, Elephantine, 1990 AD)

b. "therefore, behold, I am against you and against your rivers, and I will make the land of Egypt an utter waste and desolation, from Migdol to Syene and even to the border of Ethiopia." (Ezekiel 29:10)

c. "‘Thus says the Lord, “Indeed, those who support Egypt will fall And the pride of her power will come down; From Migdol to Syene They will fall within her by the sword,” Declares the Lord God." (Ezekiel 30:6)

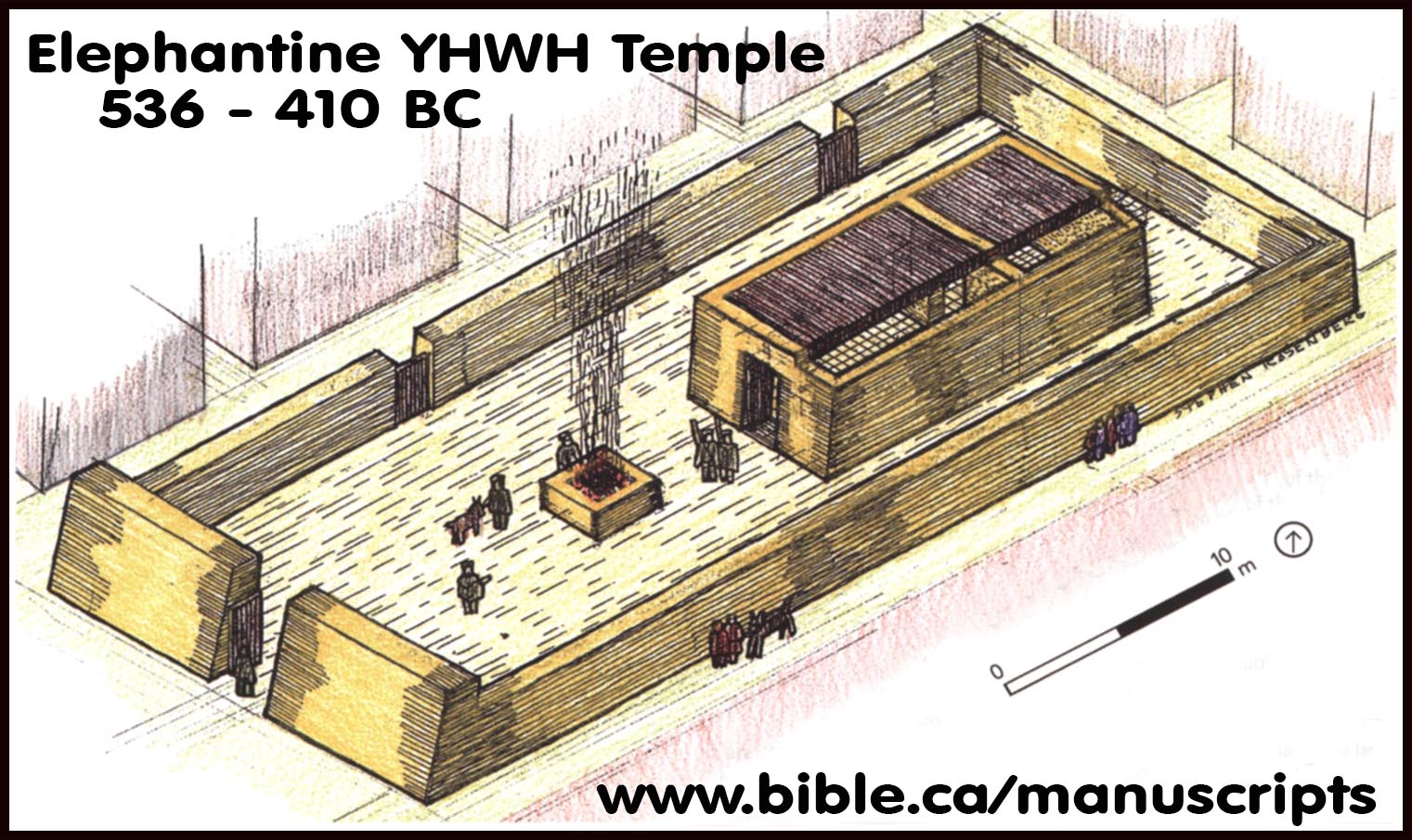

4. What we

know about the Elephantine fortress and Jewish Temple:

a. The Jewish fortress of Elephantine likely dates back to Manasseh and later fortified by Zedekiah in 593 BC and the based upon all the evidence, the YHWH temple was constructed within 10 years after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC. We know from the Elephantine Temple papyri that the temple stood at Elephantine at the time of the Persian ruler Cambyses conquered Egypt in 525 BC. With the universal decree of the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC to allow freedom of all religions, it is possible the YHWH temple at Elephantine was started after 536 BC. The Jerusalem temple was not completed until 515 BC but here construction began on the walls first and proceeded to the temple itself. They also had hindrances and delays. At elephantine they had no security issues and could immediately commence building the temple. The Jewish Elephantine temple was a simple "tabernacle of Moses" architectural design that would require a perimeter wall and a few interior walls. Such a simple structure could be built quickly. Exactly which Jews would build a temple at Elephantine?

b. The Jews living in Babylon who returned from captivity would not build a temple in both Jerusalem AND the a outpost of Elephantine. Rather they would concentrate their efforts on the Jerusalem temple. It is most likely that the resident colony of Jews at Elephantine took it upon themselves to build a replacement temple for themselves after the decree of Cyrus.

c. "According to the above-cited [Elephantine papyri] letter of Jedaniah, the Elephantine temple was constructed sometime before the Persian conquest of Egypt in 525 B.C.E.: “During the days of the kings of Egypt [i.e., when Egypt was independent] our forefathers built that temple in the Elephantine fortress and when Cambyses [the Persian ruler who conquered Egypt in 525 B.C.E.] entered Egypt, he found that temple built.” But the Jews needed more than permission from the Egyptian ruler to build a temple. According to Israelite tradition, foreign soil was impure soil. From Joshua to the prophets to the Babylonian exiles, it was understood that cultic activities should not be performed outside the land of Israel. When the cured Aramean leper Naaman wanted to worship YHWH in his homeland, he took with him two mule-loads of Israelite earth (2 Kings 5:15ff)." (Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?, Bezalel Porten, BAR, BAR 21:03, May/June, 1995 AD)

5. We have chosen to feature three spectacular historically important papyrus documents from the time of Nehemiah and Malachi during the reign of Darius II.

a. Temple of YHWH burned (Sanballat, Bagohi Governor of Judea)

b. Document of wifehood (bride price, dowry, divorce causes and penalties)

c. Passover regulations (unleavened wine and bread)

I. Authorities about the Elephantine Papyrus Letters: 495 - 399 BC

1. "Aramaic letters on papyrus number 35, not all fully intact, and many fragments. Twenty-eight belong to Elephantine (TAD A3.1–10; 4.1–10; 5.2, 5; 6.1, 2) or Syene (TAD A2.1–4) and seven elsewhere (el-Hibeh [TAD A3.11], Luxor [TAD A2.5–7], Saqqarah [TAD A5.1], unknown [TAD A5.3, 4]). Almost all were written by persons resident at Elephantine-Syene who were away from home. Four are drafts of letters sent from outside of Elephantine (TAD A4.5, 7, 8, 10) and one is strictly speaking a memorandum, probably written in Judah or Samaria (TAD A4.9). Like the contracts, the letters span the 5th century, perhaps extending back to the late 6th (TAD A2.1–4) and down into the early 4th (TAD A3.10, 11). Unlike contracts, they were usually written on both sides of the papyrus (except TAD A3.4, 9; 4.4; 5.2), the scribe writing first on the side perpendicular to the fibers, turning the piece bottoms-up and concluding on the side parallel to the fibers. Occasionally, the piece was turned sideways (TAD A3.9). One unique piece, unfortunately fragmentary, contains a letter written on the side parallel to the fibers and to the join, with the reply begun on the other side, parallel to the fibers and perpendicular to the join, and concluding in the right and left margins of the first letter (TAD A3.1). Unlike contracts which were rolled up and folded in thirds, letters were rolled up and folded in half, addressed on one of the exposed bands with the name of the sender and the recipient (and sometimes the destination [TAD A2.1–7]), and then tied and sealed just like the contracts." (ABD, Elephantine Papyri)

2. "A good deal of information concerning life in the Jewish settlement at the border station of Syene/Yeb during the fifth century B.C.E. comes from the Elephantine papyri. The papyri—Aramaic archival documents, including copies of correspondence, memoranda, contracts and other legal materials—first came to light at the end of the 19th century and were published by numerous scholars over a 60-year period (1906–1966). They have recently been the subject of intensive investigation (with corrections of some mistakes made by earlier scholars) by Bezalel Porten of Hebrew University. The documents date from 495 to 399 B.C.E. and are thus roughly contemporaneous with the reconstruction of the Jewish state under Ezra and Nehemiah; but the Jewish community at Elephantine had existed for at least a century before the earliest Elephantine documents. The most intriguing aspect of Jewish communal life at Elephantine was a temple dedicated to the Hebrew God Yahu (YHW, a variant form of YHWH). According to the papyri, the temple had been destroyed by the Egyptians at the instigation of the priests of the local cult of Kimura in the 14th year of Darius II (410 B.C.E.). Exactly when the Temple was built is unknown, but it was sometime prior to the Persian conquest of Egypt in 525 B.C.E. Jedaniah, the Jewish communal leader at Elephantine, wrote to Bagohi, the Persian governor of Judah, requesting assistance in rebuilding the Elephantine temple. Jedaniah also wrote to Delaiah and Shelemiah, the sons and successors of Sanballat, governor of Samaria, with the same request. Other correspondence with Jerusalem included requests for information on the correct procedure for observing the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Passover) and on matters of cultic purity. Although Jedaniah represented his Elephantine temple as a regular Jewish sanctuary, just like the Jerusalem Temple, scholars have tended to regard the cult of Yahu at Elephantine as a syncretistic mixture of Yahwism and Canaanite (especially northern Canaanite) cults of Bethel, Anat-Bethel, Eshem, Eshem-Bethel, Herem-Bethel and Anath-YHW. This is because the names of these deities are referred to in judicial oaths and salutations used by Jews in the Elephantine documents. Accordingly, a northern, Israelite origin of these colonists has been suggested. Porten, on the other hand, contends that “the evidence for a syncretistic communal cult of the Jewish deity dissipates upon close inspection” (although “individual Jewish contact with paganism remains”). According to Porten, the temple was established by priests from Jerusalem who had gone into self-imposed exile in Egypt during the reign of King Manasseh (c. 650 B.C.E.) to establish a purer Yahwistic temple there. Whether or not the cult of Yahu at Elephantine was syncretistic [a blend of Bible and paganism], or the Jews of Elephantine were themselves syncretistic, one thing remains clear: Pagan religion was more influential in the life of the Jews of Upper Egypt than it was in the life of Jews in Babylonia. The tradition preserved in Jeremiah 44:15-30 [in 587 BC] records the worship of a goddess called “the Queen of Heaven” (compare Jeremiah 7:18) by the Jews of Johanan ben Kareah’s community in the Pathros-Migdol area of Egypt. Similar tendencies probably prevailed among the Jews in Upper Egypt. This may explain why Jeremiah judges the Jews of Egypt so harshly. This may also be why we read nothing of the Jews of Egypt playing any sort of role in the reconstruction of the Jewish nation during the Persian period. (Ancient Israel, Exile and Return: From the Babylonian Destruction to the Reconstruction of the Jewish State, James D. Purvis, Eric M. Meyers, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2004 AD)

3. "13.6.2. The Elephantine Jewish Community: The Elephantine papyri allow us to get much closer to the daily lives of the community than is the case for most Jewish communities in the Second Temple period, sometimes even closer than in Yehud. Only a brief sketch can be given here, to supplement the history of Yehud. As it happens, the years of most knowledge about the Elephantine community come toward the end of the fifth century bce, which is why this precís is included in this chapter. A number of the documents fall into the category of ‘archive’ of a particular family or individual: Jedaniah, Mibtahiah, Anani. Especially important is the ‘communal archive’ of Jedaniah who was an important figure in the community. This archive contains a number of documents important for the temple of Yhw, including letters about Passover observance, the destruction of the temple and requests for rebuilding. Indeed, much of what we know about the community as a whole relates to the temple of Yhw. Quite a few documents mention it in passing, including those which happen to touch on property boundaries. We are fortunate in having several writings that discuss ownership of real estate property (e.g. TAD B2.1–4, B2.7, B2.10; B3.4–5, B3.7, B3.10–12=AP 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, 25; BM 3, 4, 6, 9, 10, 12), from which the actual location of different domiciles in Elephantine can be reconstructed, even if with some uncertainty (see the maps in TAD, II: 175–82; Ayad 1997). We can only guess at the origins of the colony. It may have been founded there as early as the pre-exilic period. According to one letter, the colony was flourishing with its own temple when Cambyses conquered Egypt about 525 bce (TAD A4.7.13–14//A4.8.12–13=AP 30.13–14//31.12–13). The most exciting—and distressing—event came about 410 bce when the temple was apparently destroyed by the priests carrying out the cult of the ram goat Khnum who had a temple nearby (TAD A4.7.4–13//A4.8.3–12=AP 30.4–13//31.3–12). Over a period of several years (410 until after 407 bce) requests were made to have it rebuilt. At first it was asked to restore it to its previous situation with the cult fully functioning (TAD A4.7.25–26//A4.8.24–25=AP 30.25–26//31.24–25); however, eventually the request was scaled down from offering blood sacrifices as before to the offering of only cereal and incense offerings (TAD A10=AP 33), and this was approved (TAD A9=AP 32). One cannot help wondering whether the cause—or one of the causes—of the destruction was an objection by the Khnum priests to the sacrifice of lambs at the Yhw temple. The Passover Papyrus may have been the response to a request from the Elephantine Jewish community for permission to carry on the traditional celebrations in the face of opposition, though we cannot be certain because of a missing part of the papyrus (§10.1.1). We do not know for certain whether the temple was rebuilt. A sale of property dated to 402 bce (TAD B3.12.18–19=BM 12.18–19) mentions the temple of Yhw as forming part of the boundary. There is also a list of payments or gifts of money on behalf of the Jewish garrison to ‘Yhw the god’ (though some other divine names are mentioned [§11.3.1]), dated to 400 bce (TAD C3.15=AP 22). These data could certainly be interpreted as indicating that the temple was rebuilt and back in operation, but this is not the only possibility (e.g. the lot where the temple had once stood—even if still vacant—could be written into property deeds, and silver could be given to Yhw in anticipation of reviving the cult). The documentation ceases in 399 bce, and the ultimate fate of the community is unknown.(A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Yehud: A History of the Persian Province of Judah, L. L.Grabbe, Volume 1, Pages 318–319, 2004 AD)

4. "Elephantine Papyri. A collection of Aramaic documents from the reigns of Xerxes, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II (485–404 bc), found in 1904–8 on the site of an ancient Jewish military colony which had settled at Elephantine in the far south of Upper Egypt some time before the conquest of Egypt by the Persians." (The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Elephantine Papyri, 2005 AD)

5. "The first group of papyri was purchased from dealers in 1893, but was not published until 1953. A larger collection was purchased after 1900, in stages, and published by A. H. Sayce and A. E. Cowley (1906) and E. Sachau (1911)." (Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, Elephantine Papyri, 1987 AD)

II. How papyrus legal documents were secured:

1. "Unlike contracts, they [the Elephantine Papyri] were usually written on both sides of the papyrus (except TAD A3.4, 9; 4.4; 5.2), the scribe writing first on the side perpendicular to the fibers, turning the piece bottoms-up and concluding on the side parallel to the fibers. Occasionally, the piece was turned sideways (TAD A3.9). One unique piece, unfortunately fragmentary, contains a letter written on the side parallel to the fibers and to the join, with the reply begun on the other side, parallel to the fibers and perpendicular to the join, and concluding in the right and left margins of the first letter (TAD A3.1). Unlike contracts which were rolled up and folded in thirds, letters were rolled up and folded in half, addressed on one of the exposed bands with the name of the sender and the recipient (and sometimes the destination [TAD A2.1–7]), and then tied and sealed just like the contracts." (ABD, Elephantine Papyri)

2. Papyrus legal scrolls are rolled, flattened, folded in thirds the bound with a knotted string then sealed with two pieces of clay.

a. A first piece of clay was pressed onto the knot next to the papyri.

b. The string is then bound around the first piece of clay and a second knot is tied on top of it.

c. A second piece of clay is pressed onto the first piece of clay, sandwiching the second knot between them.

d. A seal stone, often embedded in a ring worn on the finger, it pressed into the two pieces of clay to create a bulla.

3. The document is now 100% tamper

proof.

III. Jeremiah's message of doom to Judean's living in Egypt: 587 BC

1. In 587 BC, we know from Jeremiah 44:1 that Jewish settlements were established in Egypt at Pathros, Migdol, Tahpanhes, Memphis, but strangely no specific mention of Elephantine.

a. However, "Pathros derives from the Egyptian t3-p3-rsy, “the land of the south.”" which would include Cyene, Aswan and Elephantine on the border with "Cush" (ie Nubia/Ethiopia).

2. These Jews were those who had disobeyed God's command to surrender to Nebuchadnezzar but chose instead to flee to Egypt.

a. Some fled to foreign countries of Moab, Ammon and Edom: "Likewise, also all the Jews who were in Moab and among the sons of Ammon and in Edom and who were in all the other countries, heard that the king of Babylon had left a remnant for Judah, and that he had appointed over them Gedaliah the son of Ahikam, the son of Shaphan. Then all the Jews returned from all the places to which they had been driven away and came to the land of Judah, to Gedaliah at Mizpah, and gathered in wine and summer fruit in great abundance." (Jeremiah 40:11–12)

b. The army simply hid in the Judean hills until Nebuchadnezzar appointed Gedaliah and went home to Babylon: "Now all the commanders of the forces that were in the field, they and their men, heard that the king of Babylon had appointed Gedaliah the son of Ahikam over the land and that he had put him in charge of the men, women and children, those of the poorest of the land who had not been exiled to Babylon. So they came to Gedaliah at Mizpah." (Jeremiah 40:7–8)

c. Some had fled to Egypt as well.

3. After the assassination of Gedaliah in 587 BC, all the Jews who had repatriated when Nebuchadnezzar went home to Babylon migrated as a group to Egypt in direct disobedience to God:

a. Shortly after Gedaliah was killed in 587 BC: "The Lord has spoken to you, O remnant of Judah, “Do not go into Egypt!” You should clearly understand that today I have testified against you." (Jeremiah 42:19)

4. Jeremiah then visits the Jews who left after the destruction of Solomon's temple the following year.

a. "‘And I will punish those who live in the land of Egypt, as I have punished Jerusalem, with the sword, with famine and with pestilence. ‘So there will be no refugees or survivors for the remnant of Judah who have entered the land of Egypt to reside there and then to return to the land of Judah, to which they are longing to return and live; for none will return except a few refugees.’ ” Then all the men who were aware that their wives were burning sacrifices to other gods, along with all the women who were standing by, as a large assembly, including all the people who were living in Pathros in the land of Egypt, responded to Jeremiah, saying, “As for the message that you have spoken to us in the name of the Lord, we are not going to listen to you! “But rather we will certainly carry out every word that has proceeded from our mouths, by burning sacrifices to the queen of heaven and pouring out drink offerings to her, just as we ourselves, our forefathers, our kings and our princes did in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem; for then we had plenty of food and were well off and saw no misfortune. “But since we stopped burning sacrifices to the queen of heaven and pouring out drink offerings to her, we have lacked everything and have met our end by the sword and by famine.” “And,” said the women, “when we were burning sacrifices to the queen of heaven and were pouring out drink offerings to her, was it without our husbands that we made for her sacrificial cakes in her image and poured out drink offerings to her?”" (Jeremiah 44:13–19)

b. "“Nevertheless hear the word of the Lord, all Judah who are living in the land of Egypt, ‘Behold, I have sworn by My great name,’ says the Lord, ‘never shall My name be invoked again by the mouth of any man of Judah in all the land of Egypt, saying, “As the Lord God lives.” ‘Behold, I am watching over them for harm and not for good, and all the men of Judah who are in the land of Egypt will meet their end by the sword and by famine until they are completely gone. ‘Those who escape the sword will return out of the land of Egypt to the land of Judah few in number. Then all the remnant of Judah who have gone to the land of Egypt to reside there will know whose word will stand, Mine or theirs." (Jeremiah 44:26–28)

5. In 582 BC Nebuchadnezzar attacked Egypt as God had promised to kill the Jews and destroy the pagan temples in Egypt.

a. “He will also come and strike the land of Egypt; those who are meant for death will be given over to death, and those for captivity to captivity, and those for the sword to the sword. “And I shall set fire to the temples of the gods of Egypt, and he will burn them and take them captive. So he will wrap himself with the land of Egypt as a shepherd wraps himself with his garment, and he will depart from there safely. “He will also shatter the obelisks of Heliopolis, which is in the land of Egypt; and the temples of the gods of Egypt he will burn with fire." (Jeremiah 43:11–13)

b. Given how the Jews living in Egypt were so prone to paganism the temple at Elephantine, if it existed at this time, would not likely be pagan-free monument to pure Mosaic Judaism pleasing to God.

c. It seems unlikely that the Hebrew Temple at Elephantine would survive such an attack.

6. If the Elephantine YHWH temple was built before 587 it would surely be pagan because it would not be better than the paganized temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. If it was built by the Jews who left Judea 605-587 BC, it would be pagan as seen clearly in Jer 43. If it had been build by faithful Jews before 610 BC, it would have been corrupted by the new arriving Jews. Any pagan Jewish temple at Elephantine would have been destroyed in 582 BC by Nebuchadnezzar to fulfill Jeremiah 43:11–13. Nebuchadnezzar came a second time to Egypt and killed Pharaoh Hophra in 571 BC according to prophecy (Jer 44:30). So the only option left is that the Elephantine temple was built sometime after 571 BC but before 525 BC when Persian ruler Cambyses conquered Egypt in 525 BC and found the Hebrew temple standing. So the only time the Elephantine temple would have been built is at the same time as the decree of Cyrus by resident Jews stationed at the Elephantine fortress in 536 BC. This scenario gives plenty of time (11 years) to construct the simple "tabernacle of Moses-like" temple that had four walls, two interior walls and a high quality stone floor as seen in the archeological excavation plan. The Hebrew temple in Elephantine stood until it was destroyed in 410 BC by local Egyptians as seen in the Elephantine Papyri. The temple must have been in harmony with the practices at Jerusalem in the years before 410 BC with a good reputation, because they petitioned the leaders in Jerusalem to rebuild the temple as seen in the Elephantine Temple Papyri. Permission was granted (Elephantine Temple Papyri) but the temple never got built. A second modification to this scenario is that a paganized Jewish temple had existed possibly as far back as the time of Manasseh which was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar in 582 BC according to prophecy (Jeremiah 43:11–13) but rebuilt by the local resident Jews after the decree of Cyrus then destroyed forever in 410 BC.

IV. When was the Jewish Colony and temple on the island of Elephantine founded:

The Elephantine Temple papyri say that the Persian ruler Cambyses conquered Egypt in 525 BC, that he saw the temple standing. It may never know for certain but there are five theories. The most likely scenario based upon the Bible, history, the archeological dig reports and the papyrus, Elephantine was founded as a Jewish colony by Manasseh either in 667 or 650 BC and that the YHWH temple was built with ten years of the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC.

1. Founded by Manasseh in 667 BC: In 667 BC Manasseh sent troops with 21 other kings under the command of Ashurbanipal's (king of Assyria) campaign against Egypt and Nubia (Ethiopians). It may be at this time Ashurbanipal allowed Manasseh to set up the Jewish fortress on Elephantine Island on the southern border of Egypt at Nubia.

a. In 667 BC Manasseh sent troops to help Ashurbanipal fight Egypt:

b. "In my first campaign [667 BC] I [Ashurbanipal] marched against Egypt (Magan) and Ethiopia (Meluhha). Taharqa (or Tirhakah, Tarqû), king of Egypt (Muṣur) and Nubia (Kûsu), whom Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, my own father, had defeated and in whose country he (Esarhaddon) had ruled, this (same) Tirhakah forgot the might of Ashur, Ishtar and the (other) great gods, my lords, and put his trust upon his own power. He turned against the kings (and) regents whom my own father had appointed in Egypt.3 He entered and took residence in Memphis (Me-im-pi), the city which my own father had conquered and incorporated into Assyrian territory. An express messenger came to Nineveh to report to me. I became very angry on account of these happenings, my soul was aflame. I lifted my hands, prayed to Ashur and to the Assyrian Ishtar. (Then) I called up my mighty armed forces which Ashur and Ishtar have entrusted to me and took the shortest (lit.: straight) road to Egypt (Muṣur) and Nubia. During my march (to Egypt) 22 kings from the seashore, the islands and the mainland, … Ba’al, king of Tyre, Manasseh (Mi-in-si-e), king of Judah (Ia-ú-di), Qaushgabri, king of Edom, Musuri, king of Moab, Sil-Bel, king of Gaza, Mitinti, king of Ashkelon, Ikausu, king of Ekron, Milkiashapa, king of Byblos, Iakinlu, king of Arvad, AbiBa’al, king of Samsimuruna, Amminadbi, king of Beth-Ammon, Ahumilki, king of Ashdod, Ekishtura, king of Edi’li, Pilagura, king of Pitrusi, Kisu, king of Silua, Ituandar, king of Pappa, Erisu, king of Sillu, Damasu, king of Kuri, Admesu, king of Tamesu, Damusu, king of Qarti-hadasti, Unasagusu, king of Lidir, Pususu, king of Nure, together 12 kings from the seashore, the islands and the mainland … servants who belong to me, brought heavy gifts (tâmartu) to me and kissed my feet. I made these kings accompany my army over the land—as well as (over) the sea-route with their armed forces and their ships (respectively). Quickly I advanced as far as Kar-Baniti to bring speedy relief to the kings and regents in Egypt, servants who belong to me. Tirhakah, king of Egypt (Muṣur) and Nubia, heard in Memphis of the coming of my expedition and he called up his warriors for a decisive battle against me. Upon a trust (-inspiring) oracle (given) by Ashur, Bel, Nebo, the great gods, my lords, who (always) march at my side, I defeated the battle(-experienced) soldiers of his army in a great open battle. Tirhakah heard in Memphis of the defeat of his army (and) the (terror-inspiring) splendor of Ashur and Ishtar blinded (lit.: overwhelmed) him (thus) that he became like a madman. The glamor of my kingship with which the gods of heaven and nether world have endowed me, dazzled him and he left Memphis and fled, to save his life, into the town Ni’ (Thebes). This town (too) I seized and led my army into it to repose (there)." (Ashurbanipal’s Stele first campaign in 667 BC, ANET 294)

2. Founded by Manasseh in 650 BC: After being conquered by Ashurbanipal (king of Assyria) in 667 BC, Psammetichus I declares independence from Assyria in 655 BC. Elephantine may have been founded by Manasseh in 650 BC when he sent troops to help pharaoh Psammetichus I defeat Nubia (Ethiopians). However, the Jewish colony may have been set up 17 years earlier when Manasseh accompanied Ashurbanipal in his 667 BC campaign against Egypt and Nubia.

a. "A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus I (664–610 B.C.E.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt. Herodotus reports that in the reign of Psammetichus I, garrisons were posted at Elephantine, Daphnae and Marea. Perhaps as an accommodation to the Jews in Egypt who served as a buffer to renewed Assyrian control of Syro-Palestine (and also to consolidate their loyalty), Psammetichus permitted the Jews to build their temple." (Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?, Bezalel Porten, BAR, BAR 21:03, May/June, 1995 AD)

b. "From this city you make a journey by water equal in distance to that by which you came from Elephantine to the capital city of Ethiopia, and you come to the land of the Deserters. These Deserters are called Asmakh, which translates, in Greek, as “those who stand on the left hand of the king”. [2] These once revolted and joined themselves to the Ethiopians, two hundred and forty thousand Egyptians of fighting age. The reason was as follows. In the reign of Psammetichus I, there were watchposts at Elephantine facing Ethiopia, at Daphnae of Pelusium facing Arabia and Assyria, and at Marea facing Libya. [3] And still in my time the Persians hold these posts as they were held in the days of Psammetichus; there are Persian guards at Elephantine and at Daphnae. Now the Egyptians had been on guard for three years, and no one came to relieve them; so, organizing and making common cause, they revolted from Psammetichus and went to Ethiopia. [4] Psammetichus heard of it and pursued them; and when he overtook them, he asked them in a long speech not to desert their children and wives and the gods of their fathers." (Herodotus, Histories 2.30.1–4)

c. "The Jewish community at Elephantine was probably founded as a military installation in about 650 B.C.E. during Manasseh’s reign. A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus I (664–610 B.C.E.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt. Herodotus reports that in the reign of Psammetichus I, garrisons were posted at Elephantine, Daphnae and Marea. Perhaps as an accommodation to the Jews in Egypt who served as a buffer to renewed Assyrian control of Syro-Palestine (and also to consolidate their loyalty), Psammetichus permitted the Jews to build their temple. The Jews were not the only ones to benefit. The Aramean soldiers on the mainland at Aswan were also allowed to erect temples to their gods—Banit, Bethel, Nabu and the Queen of Heaven. (Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?, Bezalel Porten, BAR, BAR 21:03, May/June, 1995 AD)

d. "Psammetichus I (664–610), with the help of Gyges, king of Lydia, rebelled against Assyria in 655 b.c.e. The constant threat from Assyria might have led the pharaoh to authorize Manasseh to improve his fortifications and redeploy his troops (2 Chr 33:11–14) so that Judah could serve as a buffer state between Egypt and Assyria." (Hermeneia, 2 Chronicles 33:21-25, 2012 AD)

3. Founded by the Samaritans in 623 BC: Elephantine may have been founded as a pagan temple in rebellion to the reforms of Josiah that started in 623 BC by the Samaritans of the ten northern tribes.

a. If this is true, the Elephantine would be syncretistic [a blend of Bible and paganism], since it was what Josiah fought against.

b. They would not start a true temple in Elephantine if the Jerusalem temple was purified from paganism.

c. "If, as Cross has suggested, the memory of the Mishkan remained with the people of Israel (the northern kingdom) then their setting up of a shrine in its form would be much more likely than building one on the lines of the Solomonic Temple. It might also suit them to build a shrine in Egypt in defiance of the centralizing reforms of 622 bce by Josiah, which obviously caused much dismay among the remaining peoples of the northern kingdom." (Near Eastern Archaeology, Volume 67, Nos. 1–4, p 12, 2004 AD)

d. The condemnation of Jeremiah 44 against the Egyptian Jews for their rampant idolatry would support this proposal.

e. This is unlikely because idol worshippers in a syncretistic would not seek the approval of the Jerusalem leaders in 410 BC to rebuild such an apostate temple.

4. Founded by Zedekiah in 593 BC: Elephantine may have been founded by Zedekiah in 593 BC when he sends troops to help pharaoh Psamtik II (Psammetichus II) defeat Nubia.

a. "The historical framework of the book [Nehemiah] is confirmed by papyri which were discovered between 1898 and 1908 in Elephantine, the name of an island in the upper Nile. Here Psammetichus II (593–588 b.c.) established a Jewish colony. The Elephantine papyri are well preserved, written in Aramaic, and are the 5th-century b.c. literary remains of this Jewish colony of the Persian period." (Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, p 1537, 1988 AD)

b. "It was from this time that mercenaries began to play a significant role in the country, later forming a separate division in the Egyptian army, a fact known from texts dealing with Psammetichus II’s campaign into Nubia (see below). Garrisons were established at the south in Elephantine, and to the northeast at Daphnae. A local war with the Libyans ended successfully for Psammetichus II, and he erected a series of stelae commemorating his army’s victory over these perennial foes in regnal years 10–11 (Goedicke 1962; Basta 1968; Kitchen 1973: 405). In this case, it is clear that the Libyans actually represented Egypt’s western neighbors, rather than the former kinglets of the Delta. It is possible that a third garrison was founded on the west soon after this victory. All three were built to control the entrances into the land, since Egypt had to fear invasion from Kush (south of Elephantine), Assyria (northeast at Daphnae), and Libya (northwest at Marea). In addition, the Nile itself was supplied with an independent fleet, a forerunner of the navy developed in the East Mediterranean by later Saite monarchs. Finally, Psammetichus II allied himself to the Lydians who, under King Gyges, began to expand and form a kingdom hostile to the Assyrians (Spalinger 1978c; Millard 1979). Internally, Egypt lost much of the character of the preceding age. The ubiquitous donation stelae were still erected but now under only one king. Local independence in the north had ended by year 8 of the pharaoh and even though Libyan families still held power in some cities, their might was now subservient to the monarch. Initially, Psammetichus stressed the importance of the powerful families in Egypt, such as the Masters of Shipping at Heracleopolis and the Theban dignitaries (Kitchen 1973: 402–3). Later, he placed his adherents, most of whom came from the north, in key positions in the land (Kees 1935). However no real administrative reform took place. The local administrative units, the nomes, became tax collectors’ districts, and outmoded titles dating back to the Old and Middle Kingdoms were employed, but no major reorganization of the finances or bureaucracy was apparently needed. By simply sending his new officials to the south, Psammetichus ran the land effectively." (ABD, Egypt, Volume 2, p 360)

c. The witness of Herodotus in 484 BC says the colony was established much earlier: "In the reign of Psammetichus I, there were watchposts at Elephantine facing Ethiopia, at Daphnae of Pelusium facing Arabia and Assyria, and at Marea facing Libya. And still in my time the Persians hold these posts as they were held in the days of Psammetichus; there are Persian guards at Elephantine and at Daphnae." (Herodotus, Histories 2.30.1–4)

5. Founded by the Jews after the 587 BC destruction of the temple of the Edomites and Nebuchadnezzar.

a. The Elephantine Temple papyri says that the Persian ruler Cambyses conquered Egypt in 525 BC, that he saw the temple standing. This is the earliest extant reference to the temple.

b. About the only period the temple would be built was after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC.

c. While rebuilding Jerusalem was started at the same time, word began with the walls and the temple was not completed until 515 BC.

d. Without any of the hindrances or delays experienced by Nehemiah, it is quite reasonable for the Jewish residents at Elephantine to build their architecturally simple temple within 10 years. Work began in 535 BC and the temple was finished ten years later in 525 BC when Cambyses arrived and reported its existence.

V. Why was the Jewish Colony and temple on the island of Elephantine founded:

It may never know for certain but there are five theories. The most likely reason based upon the Bible, history, the archeological dig reports and the papyrus, is that Elephantine was always a Jewish military fortress and the YHWH temple was built because the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC allowed anyone of any religion to build a temple to any god. Being in the wilderness at the far southern border of Egypt it was like the tabernacle in the wilderness never intended to complete with or replace the Jerusalem temple.

1. A permanent Jewish military fortress at the southern border of Egypt to protect against Nubian invasions.

|

A military was certainly a fortress: Herodotus 484 BC The Elephantine Papyrus repeatedly refer to the Jewish Island colony as a "fortress. Two kings of Judah sent troops to help Egypt defeat Nubia: Manasseh and Zedekiah. The Jewish controlled fortress so far from Judah, was a kind of pledge of cooperation between the King of Judah and Pharaoh. When and why the Hebrew YHWH temple was built is uncertain. |

a. Under Manasseh, there were two times he battled Nubia. First under the command of Ashurbanipal's (king of Assyria) in 667 BC as recorded in his Nubian Victory Stele. Second in cooperation with Pharaoh Psammetichus I Nubian campaign of

b. In 484 BC Greek historian Herodotus said: "In the reign of Psammetichus I, there were watchposts at Elephantine facing Ethiopia, at Daphnae of Pelusium facing Arabia and Assyria, and at Marea facing Libya. [3] And still in my time the Persians hold these posts as they were held in the days of Psammetichus; there are Persian guards at Elephantine and at Daphnae." (Herodotus, Histories 2.30.1–4)

c. "Porten suggested that the Jews may have come to Elephantine as a military garrison in about the middle of the seventh century bce, during the reign of Manasseh in Judah, to aid Psammetichus I in his campaigns against Nubia (cf. Lewy and Lewy 1968: 135) and in an attempt to dislodge the overarching power of Assyria (Porten 1968: 119)." (Near Eastern Archaeology, Volume 67, Nos. 1–4, p 6, 2004 AD)

d. Elephantine was in fact, a foreign embassy with soldiers.

e. Archeologically, the temple at Elephantine is simplistic like the tabernacle tent set up in Samaria at Shiloh for 305 years.

f. The building of a "temple in the wilderness" after the simple pattern of the tabernacle seems to have been built.

g. The fortress came first and the temple naturally followed.

2. Restoration of temple worship to purity: A pure "pagan free" YHWH temple was built in 650 BC because of the corruption and idolatry of the Jerusalem temple.

a. "According to Porten, the temple was established by priests from Jerusalem who had gone into self-imposed exile in Egypt during the reign of King Manasseh (c. 650 B.C.E.) to establish a purer Yahwistic temple there." (Ancient Israel, Exile and Return: From the Babylonian Destruction to the Reconstruction of the Jewish State, James D. Purvis, Eric M. Meyers, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2004 AD)

3. Pagan temple in competition to Jerusalem: Elephantine was founded by the Samaritans as a pagan temple in rebellion to the reforms of Josiah that started in 623 BC.

a. Archeologically, the temple at Elephantine is simplistic like the tabernacle tent set up in Samaria at Shiloh for 305 years. The Samaritan theory suggests a simpler "tabernacle-like" worship design echoes the Shiloh years before the more complex temple of Solomon came in to being.

b. This theory is unlikely because the Samaritans indeed created a temple in competition to Jerusalem ON MOUNT GERIZIM which endured down to the first century in John 4 and the woman at the well. Also, the Elephantine papyrus notes that the Jews living in Elephantine sought permission to rebuild from Jerusalem. A rival temple would not respect or seek such advice.

c. The Samaritans formally began in 723 -538 BC: The first phase of Samaritan history is from the time of the divided kingdom to the time of Judah returned from Babylonian captivity in 538 BC. The second phase was after Judah returned from Babylonian captivity. Shalmaneser moved non-Gentile natives of Assyria (Modern Iraq, Babylon) and other places into Samaria to occupy the land to retain control. When God killed these non-Jews with lions the people requested one of the "priests" of Jeroboam's religion, to return and teach them about the "God of the land". Shalmaneser chose one of the priests who was from Bethel to move back into Canaan and educate the gentiles about this God who was killing them. Bethel was one of the two pagan altars that Jeroboam had set up. (2 Kings 17:24-41)

d. If this is true, the Elephantine would be syncretistic [a blend of Bible and paganism], since it was what Josiah fought against. They would not start a true temple in Elephantine if the Jerusalem temple was purified from paganism.

e. "If, as Cross has suggested, the memory of the Mishkan remained with the people of Israel (the northern kingdom) then their setting up of a shrine in its form would be much more likely than building one on the lines of the Solomonic Temple. It might also suit them to build a shrine in Egypt in defiance of the centralizing reforms of 622 bce by Josiah, which obviously caused much dismay among the remaining peoples of the northern kingdom." (Near Eastern Archaeology, Volume 67, Nos. 1–4, p 12, 2004 AD)

4. Replacement temple after Solomon's temple was burned in 587 BC

a. We know the fortress at Elephantine dates back to 650 BC, but we are uncertain when the temple was built.

b. Zedekiah in 593 BC supplied troops to pharaoh Psamtik II (Psammetichus II) to help him successfully defeat Nubia If permission was granted to build a Jewish temple on the Island of Elephantine at the time of Zedekiah, it was not likely completed until after the destruction of Solomon's temple in 587 BC. To suggest Zedekiah directly authorized the building of the temple is uncertain and perhaps unlikely given the Judean Negev was under attack by the Edomites starting in 605 BC until they burned Solomon's temple with the Babylonians in 587 BC.

c. While it is possible that the temple was built after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC there are some problems with this idea. The Elephantine Temple papyri says that the Persian ruler Cambyses conquered Egypt in 525 BC, that he saw the temple standing.

d. It is possible the YHWH temple at Elephantine was started after 536 BC and completed within a few years AND before the arrival of Cambyses in 525 BC. The Jerusalem temple was not completed until 515 BC but here construction began first on the walls and proceeded to the temple itself. They also had hindrances and delays which would not likely happen at Elephantine.

e. The Jewish Elephantine temple was a simple "tabernacle of Moses" architectural design that would require a perimeter wall and a few interior walls. Such a simple structure could be built quickly.

f. Exactly which Jews would build a temple at Elephantine? The Jews living in Babylon would not build a temple in both Jerusalem AND the a outpost of Elephantine. Rather they would concentrate their efforts on the Jerusalem temple.

g. It is very possible that the resident colony of Jews at Elephantine took it upon themselves to build a replacement temple for themselves when they saw the temple in Jerusalem was destroyed.

5. Parallel "temple in the wilderness" after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC

a. The most likely reason based upon the Bible, history, the archeological dig reports and the papyrus, is that Elephantine was always a Jewish military fortress and the YHWH temple was built because the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC allowed anyone of any religion to build a temple to any god.

b. Being in the wilderness at the far southern border of Egypt it was like the tabernacle in the wilderness never intended to complete with or replace the Jerusalem temple.

|

VI. Hebrew Temple of YHWH at Elephantine is burned in 410 BC |

|

|

Jewish YHWH Temple at Elephantine. While the military fortress was founded in 650 BC, the temple was built within ten years after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC and was destroyed in 410 BC. Four Temple Papyrus: |

|

A. Introduction to Elephantine Temple Papyri:

1. Four Temple Papyrus:

a. #1: Temple destruction

b. #2: Water well stopped temple destroyed

c. #3: Bribe to rebuild temple

a. #4: Jerusalem allows temple rebuild

2. See also:

a. General introduction (Founding of Elephantine, discovery of papyrus collection)

b. Document of wifehood (bride price, dowry, divorce causes and penalties)

c. Passover regulations (unleavened wine and bread)

d. Conclusion (Importance of Elephantine papyrus to the Bible)

3. The temple was burned in 410 BC and the petition to rebuild the temple sent to Jerusalem was in 406 BC:

a. "Moreover, from the month of Tammuz, year 14 of King Darius (410 BC) and until this day we are wearing sackcloth and fasting; our wives are made as widow(s); (we) do not anoint (ourselves) with oil and do not drink wine. Moreover, from that (time) and until (this) day, year 17 of King Darius (407 BC)"

4. The Elephantine Temple was built after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC before the temple in Jerusalem was finished and functioned as a parallel temple "temple in the wilderness" once the temple in Jerusalem was completed in 515 BC.

a. The Elephantine temple was up and running BEFORE the temple in Jerusalem was finished.

b. The most likely reason based upon the Bible, history, the archeological dig reports and the papyrus, is that Elephantine was always a Jewish military fortress and the YHWH temple was built because the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC allowed anyone of any religion to build a temple to any god.

c. Being in the wilderness at the far southern border of Egypt it was like the tabernacle in the wilderness never intended to complete with or replace the Jerusalem temple.

d. From the archeological and excavation reports the design was very simple and duplicated the plan of the Tabernacle of Moses from Mt. Sinai.

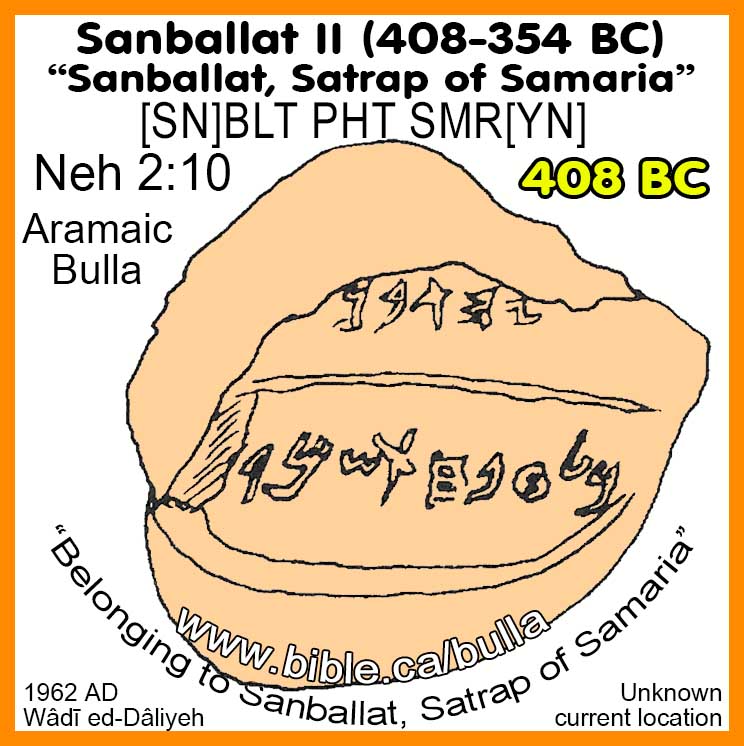

5. Important names found in the Temple Papyri:

a. Bagohi, governor of Judah (410 BC) is found in this Elephantine Temple papyri. He would have been appointed by Darius II and was a successor to Nehemiah and Ezra. More about Persian governors

b. Sanballat,

governor of Samaria (Nehemiah's enemy). Below is his clay bulla

c. Delaiah and Shelemiah are sons of Sanballat in the Elephantine letter and there is no direct connection with them in the book of Nehamiah. However both names are very common: Delaiah occurs 2x in Nehemiah. Shelemiah occurs 10x in Nehemiah. In Nehemiah 6:10 both are used. This further evidences that the letter confirms the historicity of Nehemiah. In fact Scholars believe that Nehemiah is correct and Josephus got it wrong in some basic details.

d. Jehohanan the High Priest

e. Arsames former governor of Egypt who went to visit Darius.

f. Vidranga Governor of Egypt in the absence of Arsames

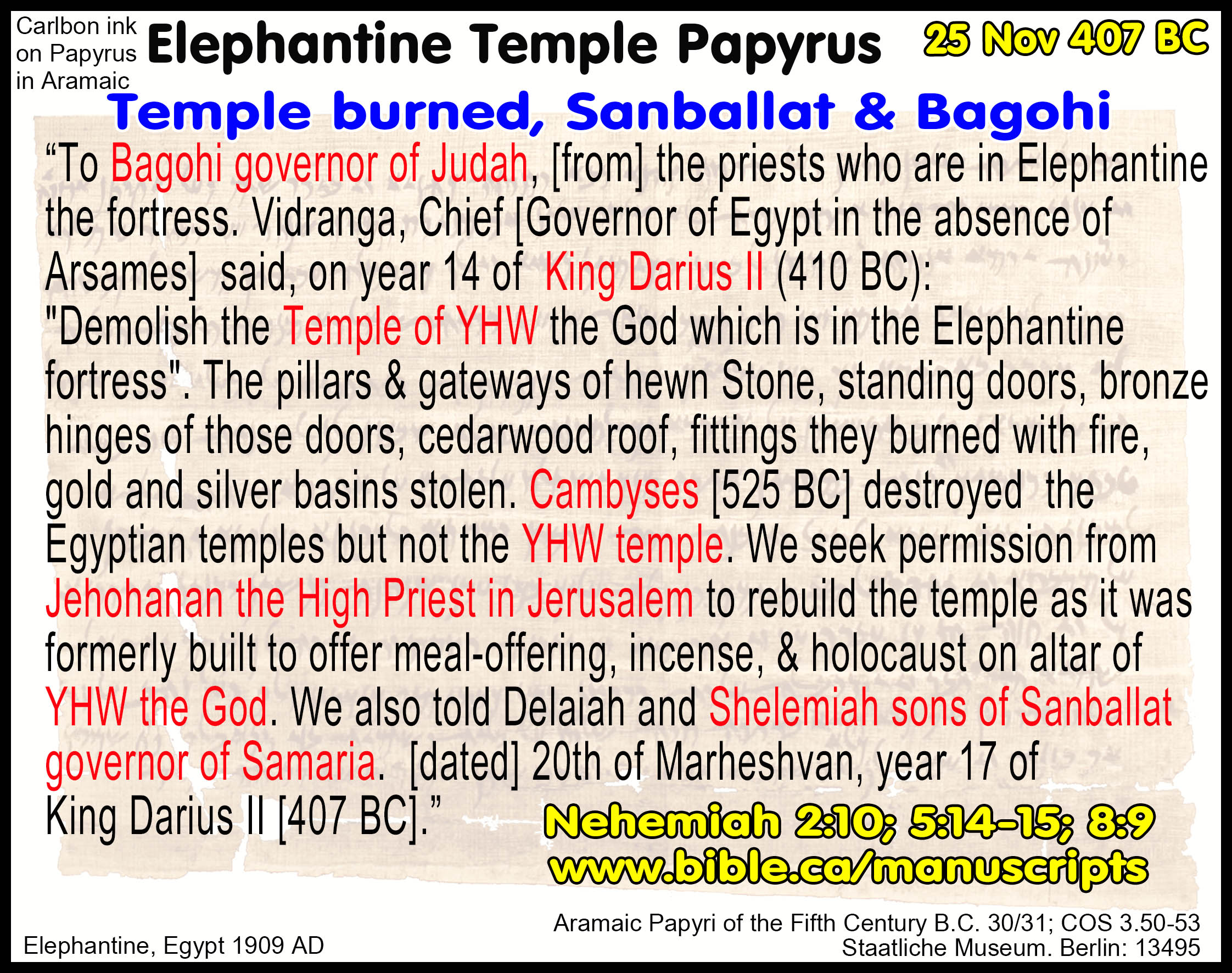

B. Elephantine Temple Papyri #1: Temple Destruction and request Bagohi to rebuilt

- Bagohi was the succeeding governor of Judea after Nehemiah. Both Bagohi and Sanballat the Horonite are named in this Elephantine Temple Papyri:

- "When Sanballat the Horonite and Tobiah the Ammonite official heard about it, it was very displeasing to them that someone had come to seek the welfare of the sons of Israel." (Nehemiah 2:10)

- "Moreover, from the day that I was appointed to be their governor in the land of Judah, from the twentieth year to the thirty-second year of King Artaxerxes, for twelve years, neither I nor my kinsmen have eaten the governor’s food allowance. But the former governors who were before me laid burdens on the people and took from them bread and wine besides forty shekels of silver; even their servants domineered the people. But I did not do so because of the fear of God." (Nehemiah 5:14–15)

- "Then Nehemiah, who was the governor, and Ezra the priest and scribe, and the Levites who taught the people said to all the people, “This day is holy to the Lord your God; do not mourn or weep.” For all the people were weeping when they heard the words of the law." (Nehemiah 8:9)

2. Discussion on Elephantine Temple Papyri #1: Temple Destruction and request Bagohi to rebuilt

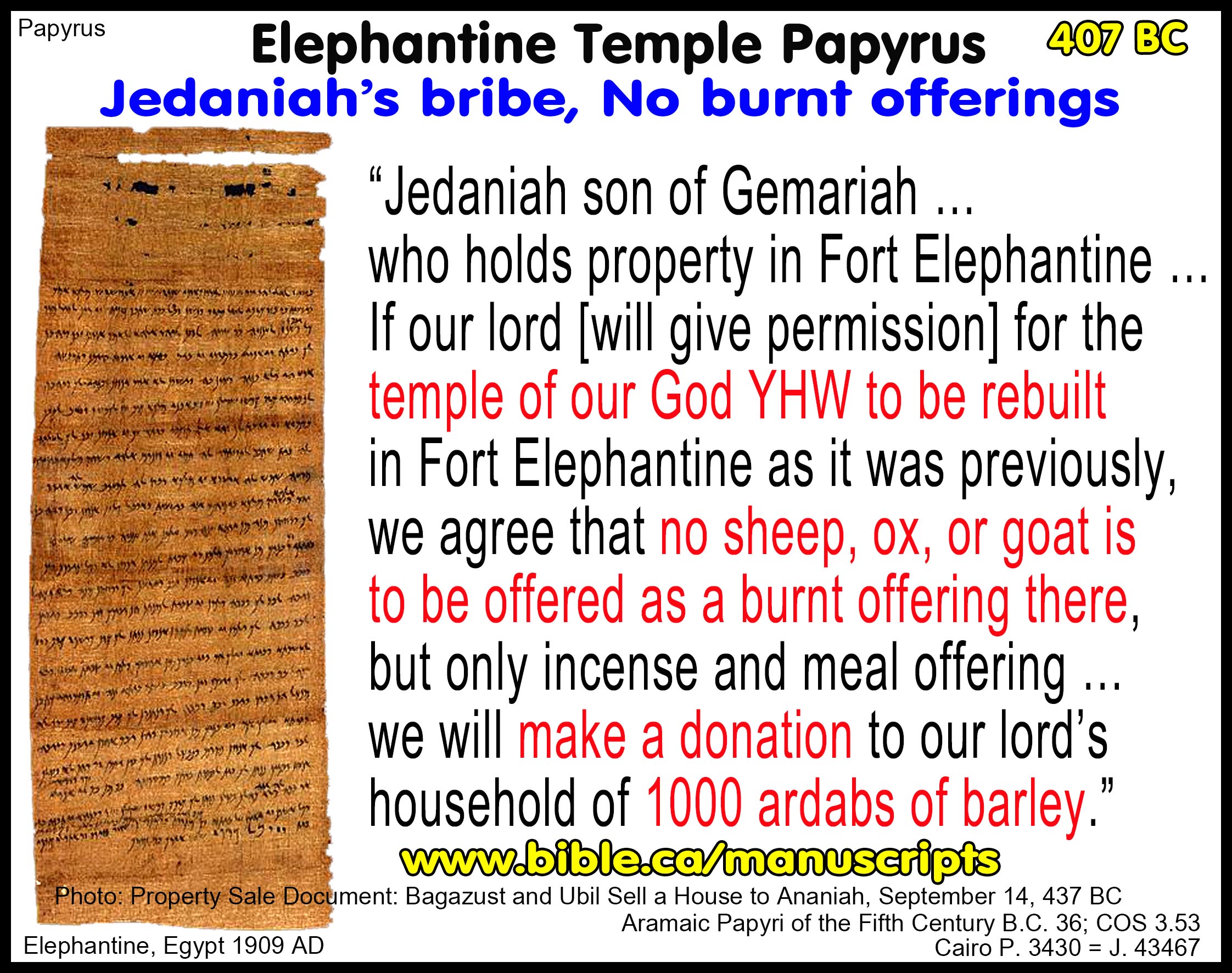

a. "One of the most interesting of the letters is that addressed by the colonists of Yeb to Bagoas, the Persian governor of Judea. It seems to have been the successor to an earlier complaint sent to a Persian official in Egypt about the wanton destruction of the temple by rebellious Egyptians in 410 b.c. That letter had apparently gone unanswered, hence the petition in 407 b.c. to Bagoas, a copy of which was kept at Yeb. The document was sent by “your servants Yedoniah and his colleagues,” and reports the shameless pillaging of the shrine. A concluding section requests official approval for the reconstruction of the building, and also states that the sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria in the time of Nehemiah, have been requested to help. If an official reply was received by the priests of Yeb, it has not survived. A memorandum has been recovered, however, which indicates that a verbal response sent to Arsames, the Persian governor in Egypt, supported the request for permission to rebuild. This is evidence that the Persian rulers took a genuine interest in the lives of their subjects, taking care to accommodate religious traditions. Meal offerings and incense are specified as the only ritual procedures to be followed, “as was done formerly.” Another smaller Aramaic text dealing with the proposed reconstruction of the temple states specifically that sheep, oxen, and goats were not offered there. Thus it is far from certain that the Passover was ever observed at Yeb, at least in its traditional form." (ISBE, Elephantine Papyri, 1988 AD)

b. "In Elephantine, the temple to the Jewish deity Yahu (a variant form of the biblical names for the God of Israel, Yah and Yahweh) was destroyed in the fifth century bc. According to correspondence with the priests in Jerusalem, the destruction was caused by priests of the Egyptian ram god Khnum—to whom a temple was built on Elephantine during the 18th–19th centuries bc (or the 16th–13th centuries bc). The Jewish community responded by praying, fasting, and putting on sackcloth, which were common biblical responses to disaster. The leaders petitioned Jerusalem to permit the rebuilding of the temple, pointing out that they had made no oil, incense, or burnt offerings in the temple since it had been destroyed—indicating both an awareness of the authority of the Jerusalem priesthood and a shared practice of presenting offerings at an authorized temple. The temple was apparently never rebuilt." (Lexham Bible Dictionary, Elephantine, 2015 AD)

c. "Historically, this is the most significant of all the Elephantine Aramaic texts (P. Berlin 13495 [TAD A4.7]). It is a well-balanced, carefully constructed bipartite petition (Report and Petition) addressed by Jedaniah, the priests, and all the Jews of Elephantine to Bagavahya, governor of Judah. It opens with a Fourfold Salutation (welfare, favor, longevity, happiness and strength) and concludes with a Threefold Blessing (sacrifice, prayer, merit). The Report has three parts: Demolition (lines 4–13), Precedents (lines 13–14), Aftermath (lines 15–22). The Demolition delineates the plot hatched between the Egyptian Khnum priests and the local Persian authorities, the Chief Vidranga and his son the Troop Commander Nafaina. The Precedents were twofold: Egyptian Pharaohs authorized the Temple’s construction and the Persian conqueror approved of its existence. The Aftermath relates the situation following the destruction: punishment of the perpetrators in response to prayer and fasting; silence of all Jerusalem authorities in the face of earlier petition; continued communal mourning; cessation of cult. The Petition sets forth the Threefold Request (take thought, regard, write) which, if successful, would lead, as indicated, to a Threefold Blessing. The letter concludes with a twofold Addendum and Date. The scribe was well-skilled in Aram. rhetorical style and cognizant of all the appropriate rhetorical formulae. His single-line message is that the perpetrator was “wicked” while the Jews were “men of goodness.” Curiously, the first eleven lines were written by one scribe (Scribe A) while a second scribe (Scribe B) began writing in line 12 in the middle of a sentence and continued until the end of the letter. He also wrote the second draft (TAD A4.8), which was a distinct effort to polish the style and perfect the orthography. The two versions were stored together and only the third dispatched to Jerusalem. A semiological analysis seeks to trace the “script” back to Neo-Assyrian complaints and petitions.3 Linguistically, the document displays features typical of Akkadian, such as subject-object-verb word order (lines 6–7, 14, 15) and its language has been designated “Official Aramaic of the Eastern type.” Bare traces of the Temple itself may have been uncovered in recent excavations." (Context of Scripture, Bezalel Porten, COS 3.51, 2003 AD)

d. "A written reply to Jedaniah’s letter has not been discovered; probably an oral response was brought back by the messenger who delivered the letter to Bagohi. This memorandum (opposite, bottom), written in the first person on a torn piece of papyrus and corrected by erasures and marginal additions, suggests that the Elephantine community did receive a response allowing them to rebuild the temple where meal- and incense-offerings could be offered: Memorandum. What Bagohi and Delaiah said to me. Memorandum. Saying, “You may say in Egypt before Arsames about the Altar-House of the God of Heaven which in Elephantine the fortress built was formerly before Cambyses (and) which Vidranga, that wicked (man) demolished in year 14 of King Darius: to (re)build it on its site as it was formerly and the meal-offering and the incense they shall offer upon that altar just as formerly was done.” In a draft letter to a high Persian official, Jedaniah and his colleagues clearly state that they will not make burnt-offerings at the temple if they are allowed to rebuild it: Your servants—Jedaniah son of Gema[riah] by name, 1 Mauzi son of Nathan by name, [1] Shemaiah son of Haggai by name, 1, Hosea son of Jathom by name, 1 Hosea son of Nattun by name, 1: all (told) 5 persons, Syenians who are herdi[tary property-hold]ers in Elephantine the fortress—thus say: If our lord [ … ] and our Temple of YHW the God be (re)built in Elephantine the fortress as it former[ly] was [bu]ilt—and sheep, ox, and goat as burnt-offering are [n]ot made there but (only) incense (and) meal-offering [they offer there]—and should our lord mak[e] a statement [about this, then] we shall give to the house of our lord si[lver … and] a thousa[nd] ardabs of barley. (Translations by Bezalel Porten.)" (Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?, Bezalel Porten, BAR, BAR 21:03, May/June, 1995 AD)

e. "The four remaining letters concern the most traumatic incident in the history of the Jews of Elephantine: the razing of their temple in 410 B.C.E. Number 33 sets the stage. Written to a Persian official whose name is lost, it accuses the Egyptian priests of bribing Vidranga, the corrupt district governor, and then running riot in the Jewish quarter of the island, stopping up a well and building a wall in the middle of the fortress. The writers demand a hearing before the regional judiciary, so that blame can be apportioned. The fragmentary conclusion alludes to vandalism in the temple and requests an injunction to prevent any such incidents in the future. Number 34 describes the actual destruction of the temple, which took place shortly afterwards. This letter is extant in two copies, with slight textual differences. “Text A,” evidently a preliminary draft, is complete and has been taken as the primary basis for the translation, although the more fragmentary “Text B” is probably closer to the version actually sent. Addressed to the governor of Judah from Yedanyah on behalf of the entire community, no. 34 is a formal petition for permission to rebuild the temple and reinstitute sacrifice. Written three years after the events, it narrates in vivid detail what happened in 410. With the collusion of the local Persian authorities, Egyptian soldiers from Syene forced their way into the temple, plundered it, and burned it. Full of indignation and bitterness, the Jewish writers observe that their temple had stood for over a century, since before the time of Cambyses (529–522 B.C.E.). They go on to describe the community’s liturgical response: wearing of sackcloth, fasting, abstention from sexual relations, and a vindictive curse against the hated Persian governor, Vidranga, reminiscent in tone of the conclusion to Psalm 137. The writers allude to complaints, never answered, which they sent to religious officials in Jerusalem immediately after the event. They also state that reports were sent to Samaria, to the administrative authorities Delayah and Shelemyah, sons of Nehemiah’s old nemesis, Sanballat (Sin-uballit). The administrative relationship between Judah and Samaria at this time remains one of the many historical unknowns of the period. Yedanyah and his associates take care to exonerate the satrap Arshama from any complicity in the outrage. Number 35 is the reply—or rather a succinct memorandum giving the gist of the reply—perhaps taken down orally from a courier. The Judean governor Bagavahya and Delayah of Samaria grant permission for the temple to be reconstructed and its meal and incense offerings restored. Notably absent is any permission to reinstitute animal sacrifice, as the petitioners had requested. Whether this is an accommodation to Egyptian sensitivities or a desire on the part of Persian and Jewish authorities in Palestine to downgrade the importance of the Elephantine shrine is unknown. Letter no. 36 belongs to the same sequence of events, although its relationship to no. 35 is unclear. Like no. 35, it is a rough draft or an abbreviated file copy. The unnamed addressee was probably Arshama, the satrap (see the introduction to ch. 5), for his permission to rebuild would surely have been required. Conceding the restriction against animal sacrifice, the community leaders ask for permission to rebuild, offering a “donation” (evidently a euphemism for a bribe) to encourage the recipient to decide in their favor. Whether the temple was actually rebuilt is impossible to say. Legal documents dated after 407 describe nearby property lines with reference to the temple precincts. But the site could have been used as a reference point even if it remained in ruins. If the sanctuary was restored, it was not used for long. The last datable document from the Jewish colonists is a fragmentary letter (not included here) from 399 B.C.E. alluding to the accession of the Egyptian king Nepherites, founder of the Twenty-Ninth Dynasty (Kraeling 1953: no. 13). With the end of Persian hegemony in Egypt, the colony vanished without a trace." (Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters, J. M. Lindenberger, p 63, 2003 AD)

3. Translations of the Elephantine Temple Papyri #1: Temple Destruction and request Bagohi to rebuilt

|

“To Bagohi governor of Judah, [from] the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress. Vidranga, Chief [Governor of Egypt in the absence of Arsames] said, on year 14 of King Darius II (410 BC): "Demolish the Temple of YHW the God which is in Elephantine fortress". The pillars and gateways of hewn Stone, standing doors, bronze hinges of those doors, cedarwood roof, fittings they burned with fire, gold and silver basins stolen. Cambyses [525 BC] destroyed the Egyptian temples but not the YHW temple. We seek permission from Jehohanan the High Priest in Jerusalem to rebuild the temple as it was formerly built to offer meal-offering, incense, & holocaust on altar of YHW the God. We also told Delaiah and Shelemiah sons of Sanballat governor of Samaria. [dated] 20th of Marheshvan, year 17 of King Darius II [407 BC].” (Steve Rudd translation adapted from COS) |

a. "To our lord Bagohi [or Bigvai or Bagavahya depending on translator] governor of Judah, your servants Jedaniah and his colleagues the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress. May the God of Heaven seek after the welfare of our lord abundantly at all times, and grant You favor before King Darius and the princes a thousand times more than now, and give you long life, and may you be happy and strong at all times. Now, your servant Jedaniah and his colleagues say thus: In the month of Tammuz year 14 of King Darius, when Arsames [former governor of Egypt] had departed and gone to the king, the priests of Khnub who are in Elephantine the fortress, in agreement with Vidranga [or Waidrang depending on translator] who was Chief [Governor of Egypt in the absence of Arsames] here, (said), saying, "Let them remove from there the Temple of YHW the God which is in Elephantine the fortress". Then, that Vidranga, the wicked, sent a letter to Naphaina his son, who was garrison commander in Syene the fortress, saying, "Let them demolish the Temple which is in Elephantine the fortress". Then, Naphaina led the Egyptians with the other troops. They came to the fortress of Elephantine with their weapons, broke into that Temple, demolished it to the ground, and the stone pillars which were there — they smashed them. Moreover, it happened (that) they demolished stone gateways, built of hewn stone, which were in that Temple. And their standing doors, and the bronze hinges of those doors, and the cedarwood roof — all of (these) which, with the rest of the FITTINGS and other (things), which were there — all (of these) they burned with fire. But the gold and silver basins and (other) things which were in that Temple — all (of these) took and made their own. And during the days of the king(s) of Egypt our fathers had build that Temple in Elephantine the fortress and when Cambyses entered Egypt he found that Temple built. And they overthrew the temples of the gods of Egypt, all (of them), but one did not damage anything in that Temple. And when this had been done (to us), we with our wives and our children were wearing sackcloth and fasting and praying to YHW the Lord of Heaven who let us gloat over that Vidranga. The DOGS removed the fetter from his feet and all goods which he had acquired were lost. And all persons who sought evil for that Temple, all (of them), were killed and we gazed upon them. Moreover, before this — at the time that this evil was done to us — we sent a letter (to) our lord, and to Jehohanan the High Priest and his colleagues the priests who are in Jerusalem, and to Ostanes brother of Anani and the nobles of the Jews. They did not send us a single letter. Moreover, from the month of Tammuz, year 14 of King Darius and until this day we are wearing sackcloth and fasting; our wives are made as widow(s); (we) do not anoint (ourselves) with oil and do not drink wine. Moreover, from that (time) and until (this) day, year 17 of King Darius they did not make meal-offering and ince[n]se and holocaust in that Temple. Now, your servants Jedaniah and his colleagues and the Jews, all (of them) citizens of Elephantine, say thus: If it please our lord, take thought of that Temple to (re)build (it) since they do not let us (re)build it. Regard your obligees and your friends who are here in Egypt. Let a letter be sent from you to them about the Temple of YHW the God to (re)build it in Elephantine the fortress just as it was formerly built. And they will offer the meal-offering and the incense, and the holocaust on the altar of YHW the God in your name and we shall pray for you at all times — we and our wives and our children and the Jews, all (of them) who are here. If they do thus until that Temple be (re)built, you will have a merit before YHW the God of Heaven more than a person who offers him holocaust and sacrifices (whose) worth is as the worth of silver, 1 thousand talents and [about] gold. Because of this we have sent (and) informed (you). Moreover, we sent all the(se) words [in our name] in one letter to Delaiah and Shelemiah sons of Sanballat governor of Samaria. Moreover, Arsames [former governor of Egypt who had left to visit Darius] did not know about this which was done to us [at all] On the 20th of Marheshvan, year 17 of King Darius." (Textbook of Aramaic documents from ancient Egypt vol. 1 - Letters, Ada Yardeni, Bezalel Porten, p71, 1986 AD)

b. [Internal Address] (Recto) To our lord Bagavahya governor of Judah, your servants Jedaniah and his colleagues the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress. [Fourfold Salutation] The welfare of our lord may the God of Heaven seek after abundantly at all times, and favor may He grant you before Darius the king and the princes more than now a thousand times, and long life may He give you, and happy and strong may you be at all times. [Report] Now, your servant Jedaniah and his colleagues thus say: Plot In the month of Tammuz, year 14 of Darius the king, when Arsames left and went to the king, the priests of Khnub the god who (are) in Elephantine the fortress, in agreement with Vidranga who was Chief here, (said), saying: “The Temple of YHW the God which is in Elephantine the fortress let them remove from there.” Order Afterwards, that Vidranga, the wicked, a letter sent to Nafaina his son, who was Troop Commander in Syene the fortress, saying: “The Temple which is in Elephantine the fortress let them demolish.” [Demolition of temple] Afterwards, Nafaina led the Egyptians with the other troops. They came to the fortress of Elephantine with their implements, broke into that Temple, demolished it to the ground, and the pillars of stone which were there — they smashed them. Moreover, it happened (that the) five gateways of stone, built of hewn stone, which were in that Temple, they demolished. And their standing doors, and the pivots of those doors, (of) bronze, and the roof of wood of cedar — all (of these) which, with the rest of the fittings and other (things), which were there — all (of these) with fire they burned. But the basins of gold and silver and the (other) things which were in that Temple — all (of these) they took and made their own. [Precedents] And from the days of the king(s) of Egypt our fathers had built that Temple in Elephantine the fortress and when Cambyses entered Egypt — that Temple, built he found it. And the temples of the gods of Egypt, all (of them), they overthrew, but anything in that Temple one did not damage. [Aftermath] [Mourning I] And when (the) like (s of) this had been done (to us), we, with our wives and our children, were wearing sackcloth and fasting and praying to YHW, the Lord of Heaven, who let us gloat over that Vidranga, the cur. They removed the fetter from his feet and all goods which he had acquired were lost. [Punishment] And all persons who sought evil for that Temple, all (of them), were killed and we gazed upon them? [Appeal] Moreover, before this, at the time that this evil (Verso) was done to us, a letter we sent (to) our lord, and to Jehohanan the High Priest and his colleagues the priests who are in Jerusalem, and to Avastana the brother of Anani and the nobles of the Jews. A letter they did not send us. [Mourning II] Moreover, from the month of Tammuz, year 14 of Darius the king and until this day, we have been wearing sackcloth and have been fasting; the wives of ours like a widow have been made; (with) oil (we) have not anointed (ourselves), and wine have not drunk. [Cessation of Cult. i.e. temple worship] Moreover, from that (time) and until (this) day, year 17 of Darius the king, meal-offering and ince[n]se and burnt-offering they did not make in that Temple. [Petition] Now, your servants Jedaniah and his colleagues and the Jews, all (of them) citizens of Elephantine, thus say: [Threefold Request] If to our lord it is good, take thought of that Temple to (re)build (it) since they do not let us (re)build it. Regard your ob/ligees and your friends who are here in Egypt. May a letter from you be sent to them about the Temple of YHW the God to (re)build it in Elephantine the fortress just as it had been built formerly. [Threefold Blessing] And the meal-offering and the incense and the burnt-offering they will offer on the altar of YHW the God in your name and we shall pray for you at all times — we and our wives and our children and the Jews, all (of them) who are here. If thus they did until that Temple be (re)built, a merit it will be for you before YHW the God of Heaven (more) than a person who will offer him burnt-offering and sacrifices (whose) worth is as the worth of silver, 1 thousand talents, and about gold. About this we have sent (and) informed (you). [Addendum I] Moreover, all the (se) things in a letter we sent in our name to Delaiah and Shelemiah sons of Sanballat governor of Samaria. [Addendum II] Moreover, about this which was done to us, all of it, Arsames did not know. [Date] On the 20th of Marcheshvan, year 17 of Darius the king." (Context of Scripture, Bezalel Porten, COS 3.51, 2003 AD)

c. "1To our lord Bagavahya, governor of Judah, from your servants Yedanyah and his colleagues the priests at Fort Elephantine. 2May the God of heaven richly bless our lord always, and may he put you in the good graces of King Darius 3and his household a thousand times more than now. May he grant you long life, and may you always be happy and strong! 4Your servant Yedanyah and his colleagues report to you as follows: In the month of Tammuz in the fourteenth year of King Darius, when Arshama 5left and returned to visit the court, the priests of the god Khnum in Fort Elephantine, in collusion with Vidranga, the military governor here, 6said, “Let us get rid of the temple of the God YHW in Fort Elephantine!” Then that criminal Vidranga 7wrote a letter to his son Nafaina, commandant at Fort Syene, as follows, “Let the temple in Fort Elephantine 8be destroyed!” So Nafaina came at the head of some Egyptian and other troops to Fort Elephantine with their pickaxes. 9They forced their way into the temple and razed it to the ground, smashing the stone pillars there. The temple had 10–12five gateways built of hewn stone, which they wrecked. They set everything else on fire: the standing doors and their bronze pivots, the cedar roof—everything, even the rest of the fittings and other things. The gold and silver basins and anything else they could find in the temple, 13they appropriated for themselves! Our ancestors built that temple in Fort Elephantine back during the time of the kings of Egypt, and when Cambyses came into Egypt, 14he found it already built. They pulled down the temples of the Egyptian gods, but no one damaged anything in that temple. 15After this had been done to us, we with our wives and our children put on sackcloth and fasted and prayed to YHW the lord of heaven: 16“Show us our revenge on that Vidranga: May the dogs tear his guts out from between his legs! May all the property he got perish! May all the men 17who plotted evil against that temple—all of them—be killed! And may we watch them!” Some time ago, when this evil 18was done to us, we sent letters to our lord, to Yehohanan the high priest and his colleagues the priests in Jerusalem, to Avastana, brother 19of Anani, and to the Judean nobles. None of them ever replied to us. From the month of Tammuz in the fourteenth year of King Darius 20until this very day, we have continued wearing sackcloth and fasting. Our wives are made like widows. We do not anoint ourselves with oil, 21nor do we drink wine. And from that time until this, the seventeenth year of King Darius, no meal offering, incense, or burnt offering 22has been offered in the temple. Now your servants Yedanyah, his colleagues, and all the Jews, citizens of Elephantine, petition you as follows: 23If it please our lord, let consideration be given to the rebuilding of this temple, for they are not allowing us to rebuild it. Take care of your loyal 24clients and friends here in Egypt. Let a letter be sent to them from you concerning the temple of the God YHW, 25allowing it to be rebuilt in Fort Elephantine just as it was formerly. If you do so, meal offerings, incense, and burnt offerings will be offered 26in your name on the altar of the God YHW. We will pray for you constantly—we, our wives, our children, the Jews—27everyone here. If this is done, so that the temple is rebuilt, it will be a righteous deed on your part before YHW the God of 28heaven, more so than if one were to offer him burnt offerings and sacrifices worth a thousand silver talents, and gold. Thus 29we have written to inform you. We also reported the entire matter in a letter in our name to Delayah and Shelemyah, sons of Sin-uballit (Sanballat), governor of Samaria. 30Also, Arshama did not know anything about all these things that were done to us. Date: The twentieth of Marheshwan, seventeenth year of King Darius." (Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters, J. M. Lindenberger, Razing of Temple and Petition for Aid, 410 BC, 34, p 72, 2003 AD)

D. Elephantine Temple Papyri #2: "Water well stopped up and Temple Destruction" (no photo)

1. Discussion about the Elephantine Temple Papyri #2: "Water wells stopped up and Temple Destruction"

a. Water wells stopped up and Temple Destruction: "This letter (Strasbourg Aram. 2 [TAD A4.5]) was written not in a single vertical column, like the other letters, but in two parallel horizontal columns on the recto and a single vertical column on the verso. An estimated three lines are missing at the top and bottom of each column. Writing to an unknown official, the Jews protested their loyalty at the time of the (recent or earlier?) Egyptian rebellion (lines 2–4). In the summer of 410 bce, when Arsames left to visit the king, the Khnum priests bribed Vidranga to allow partial destruction of a royal storehouse to make way for a wall (lines 4–5), apparently the ceremonial way leading to the shrine of the god, as reported in the contracts of Anani (3.78:8–9; 3.79:4). Furthermore, the priests stopped up a well that served the forces during mobilization (lines 6–8). Inquiry undertaken by the judges, police, and intelligence officials would confirm the facts as herein reported (lines 8–10). The very fragmentary column on the verso referred to Temple sacrifices and included a threefold petition, apparently for protection and the Temple’s reconstruction (lines 11–24). The subject-object-verb word order (lines 1, 8), a pattern typical of Akkadian, was standard in the official petitions (see 3.51:6–7, 15; 3.53:12) and in the Arsames correspondence." (COS, Bezalel Porten, Petition for Reconstruction of Temple, draft, 3.50, 2003 AD)

2. Translations of the Elephantine Temple Papyri #2: "Water wells stopped up and Temple Destruction"