593 BC Nubian Expedition of Psammetichus II

Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library: 414 BC

Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1

|

Digging up Bible stories! Edom was founded by Esau, twin brother of Jacob (born 2006 BC) in 1926 BC (Age 30), when Esau moves to Seir and conquers the Horites (Deut 2:12,22). Esau goes extinct in 500 BC. Detailed outline on Edom.

|

Introduction:

- Pharaoh Psammetichus II (Psamtik II) 595-589BC has five important events:

a. 593 BC: Psammetichus II's successful campaign in Nubia (victory inscription)

b. ???595 BC: Founding of Jewish colony at Elephantine

c. 592 BC: Psammetichus II's visit to (Khor) Judea and Philistia (Demotic Papyri)

d. 592 BC: Psammetichus II as one of the two eagles of Ezekiel 17

e. 589 BC: Psammetichus II's support of Zedekiah's rebellion to Nebuchadnezzar

2. "Khor" includes Judah, Phoenicia, Syria

a. "At the time of the New Kingdom Khor was the name of south-western Palestine" (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

- "The land of Khor, or Hor/Hurru, refers in Egyptian texts to Syro-Palestine [Judah]." (The Murder of Sennacherib and Related Issues. W. H. Shea, The Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin, 46, p 37, 2001 AD)

- Catalogue of the Demotic Papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD

- See Zedekiah, King of Judah: Detailed outline.

The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD

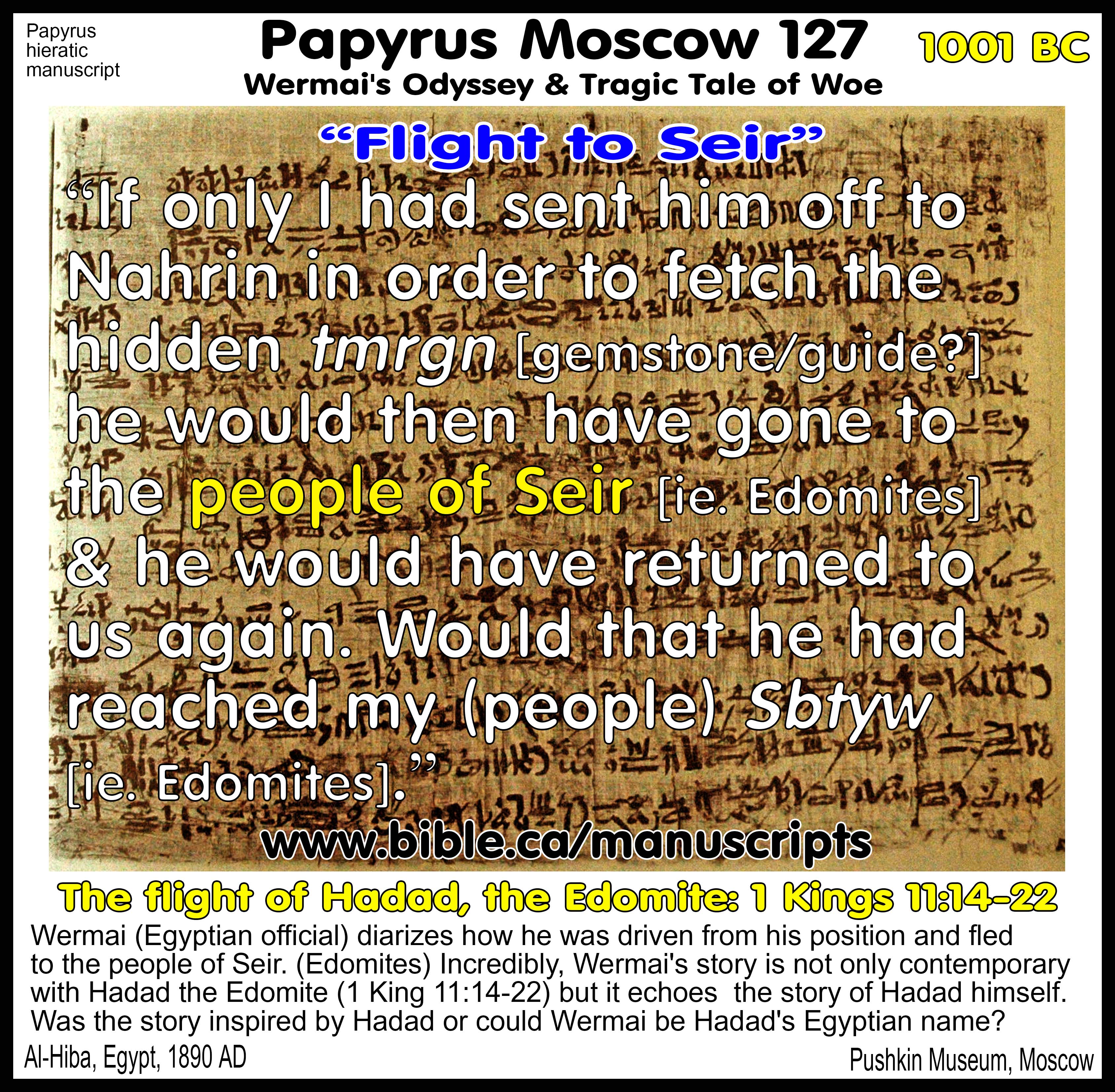

I. Translation of Papyrus Moscow 127:

|

"If (I) o |

1. (Column 14, line 16) And in the 4th year of (line 17) Per'o [Per'o = Pharaoh hereafter] Psammetk Nefrebre messages were sent to the great temples of Upper and Lower Egypt, saying, Pharaoh goeth to the land of Khor [Judea, Philistia, Syria]: let (line 18) the priests come with the bouquets (?) of the gods of Kemi to take them to the land of Khor with Pharaoh.' And a message was sent to Teuzoi, (line 19) saying, ' Let a priest come with the bouquet of Amon to go to the land of Khor with Pharaoh.' And the priests assembled and agreed in (line 20) saying to Peteesi son of Essemteu, Thou art he that art meet [capable] to go to the land of Khor with Pharaoh there is no man [here] in this city who (line 21) can go to the land of Khor except thee. Behold, thou art a scribe of the House of Life there is not a thing that they shall ask thee to which there is not a suitable answer (?). (line 22) For thou art the prophet of Amin, and the prophets of the great gods of Kemi are they who are going to the land of Khor with Pharaoh.' They (Column 15, line 1) persuaded Peteesi to go to the land of Khor with Pharaoh, and he equipped (?) himself (for the journey). Peteesi son of Essemteu went to the land of Khor, no man (line 2) accompanying him except his servant and one guard (?) named Usirmose. And when the priests knew that Peteesi had gone to the land of Khor with Pharaoh (line 3) they went to Haruoz son of Harkhebi, a priest of Sobk, who was ruler of Hnest, and said to him, Doth his Honour know the fact that the share of the prophet of Amtin of Teuzoi is Pereo's share, and it belongeth to (line 4) his Honour ? Now, Peteesi son of Ieturoii, a priest of Amun, took it when he was Ruler in Hnes, and behold it is held by his son's soli until now.' And Hamuoz son of Harkhebi said unto them, ' Where is he, his son ? ' (line 5) and the priests said to him, We have caused him to go to the land of Khor with Pharaoh. Let Ptahnufi son of Haruoz come to Teuzoi, that we may write him a title to the share of the prophet of Amun.' And Haruoz made (line 6) Ptahnufi son of Haruoz, his son, come to Teuzoi, and they wrote him a title to the share of the prophet of Amun of Teuzoi. They divided the other sixteen shares unto the four orders, four shares to each order. And they went to fetch (line 7) Ptahnufi son of Haruoz, and brought him and caused him to anoint the hands' and to perform service to Amun. Peteesi son of Essemteu came down from the land of Khor (line 8) and reached Teuzoi, and everything that the priests had done was told to him. Peteesi hastened northward to the gate of the House of Pharaoh, but he was treated contemptuously (?), and they said unto him, 'Destruction ! Pharaoh is (line 9) sick, Pharaoh cometh not out.' And Peteesi made plea unto (?) the judges (?). They brought Ptahnufi son of Haruoz, and their declarations were written in the House of Judgement, (line 10) saying, This share which Ptahnufi hath taken, his father being Master in Hnes, is Pharaoh's share.' Peteesi son of Essemteu spent many days (?) in the House of Judgement (line 11) (striving) with Ptahnufi son of Haruoz. And Peteesi was worsted in the House of Judgement, and came south ; and he went away to Ne, saying, I go to let my brethren (line 12) who are in Ne know it,' and found the sons of Peteesi son of Ieturoti who were priests of Amin in Ne ; and he told them every event that happened to him with the priests of Arnim of (line 13) Teuzoi. And they took Peteesi and made him stand before the priests of Arnim, and the priests of Arnim said unto him, ' What is it of which thou sayest " Do it" ? It hath befallen that report hath been sent (line 14) to the priests of Amin, saying, " Pharaoh Psammetk Nefrebre hath deceased (?)." Behold, when they said "Pharaoh hath deceased (?)" we were about to send to the House of Pharaoh concerning everything (line 15) that these priests of a man have done unto thee : thou shouldest (?)1 make plea (?) unto these (judges ?) who have given their declarations in writing in the House of Judgement against this priest of Sobk who taketh of (?) thy share, (line 16) for they will not be able to have leisure to finish an affair of thine in this length of time (?).' The priests caused 5 pieces of silver to be given to Peteesi, and his brethren gave him five more, in all to pieces of silver, and they said to him, ' Go to the House (line 17) of Judgement against this man who taketh of (?) thy share ; when thou spendest this silver, come that we may give thee other silver.' Peteesi son of Essemteu came north (line 18) and reached Teuzoi, and the men with whom he stood said unto him, ' There is no profit in going to the House of Judgement ; thy adversary in speech is richer than thou. If (line 19) there be a hundred pieces of silver in thy hand he will defeat thee.' And they persuaded Peteesi not to go to the House of Judgement. The priests did not give stipend (line 20) for the sixteen shares which the priests had divided to the orders, but the priests who happened to enter did service in their name, and stipend of four was given to Ptahnafi (Column 16, line 1) in the name of the share of the prophet of Amon, from the first year of Pharaoh Uehabre [throne name of Psammetichus II unto the fifteenth year [555 BC] of Pharaoh Ahmosi [Amasis 570-526 BC]. [" (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

The Expedition of Psammetichus II

1. "The following section gives us the information that Psammetichus II visited ' the land of Khor ' in his 4th year, accompanied by a number of priests, and that soon after his return he was sick and died. We already knew that he died after 5 1/2 years of reign, but an inscription found in 1904 by M. LEGRAIN shows that the date of his death was the 23rd Thoth of his 7th year. Herodotus, who calls the king Psammis, tells us that his death occurred almost immediately after a military expedition to Ethiopia [Nubia]." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

2. "Although there is nothing in the papyrus to prove that the expedition to the land of Khor was military, it seems most probable that it was so, and it is tempting to suppose that both statements refer to the same expedition. But if so one or other of the authorities must be in error, for the 'land of Khor' cannot be Ethiopia, but must either be Phoenicia or, in a more general sense, the coast regions of Palestine and Syria." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

3. "At the same time it is possible that both authorities are correct, and that the two expeditions really took place as they are represented ; there is just room to place the Ethiopian expedition between the king's return from Syria and his death, and Peteesi does not mention matters that do not concern the subject of his petition. Herodotus also, who is surprisingly accurate as to the succession of the kings and length of the reigns of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, may be given some credence in regard to what he records of their acts, although it can hardly be taken as evidence against the probability of an expedition to Syria that he has not noticed it. For instance, he records Needs' success in Syria, but makes no mention of any subsequent loss of territory, although there is fairly good evidence elsewhere to indicate that it was brought about by a disaster in which Neco's himself with his army was involved." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

4. "Unfortunately so little is known of the history of the time that there is seldom any possibility of checking the statements by incontrovertible evidence. In his account of events under Psammetichus I Peteesi has shown himself a most untrustworthy guide, his statements being at variance with facts, and sometimes scarcely to be reconciled with the copies of documents which he appends to his narrative. - But his accuracy ought to increase as he approaches nearer to his own day. The narrative has leaped forward to about 590 B.C., and the petitioner is now dealing with matters little removed from the reach of his own recollection, as will appear from the following considerations: "Shortly after the 15th year of Amasis Peteesi was a scribe and priest of Ammon, and treated at least as grown up '. He must therefore have been born not later than the first year of Amasis, B.C. 570, only 20 years after the expedition to Khor. Again, Peteesi is represented as 'old' in the 9th year (512 B.c.) of Darius'. According to the last calculation he would then be at least 57 years old, agreeing sufficiently with this datum. But further, the Peteesi who made the contract No. VIII, ill the 8th year of Amasis, c. 562 B.C., is in all probability identical with Peteesi (III), the petitioner. This would necessitate an earlier date for his birth than that just suggested." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

5. "The papyrus was probably written not long after the 9th year of Darius II [414 BC], say, 8o years after the date of the expedition, when the event would be still within the recollection of the oldest contemporaries of Peteesi. For the petitioner himself, the injury inflicted on his grandfather while absent on the expedition was a turning-point in the family fortunes, and it must have been constantly kept in his memory by his father, and had been brought up by himself and his patron in the courts of law." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

6. "The monuments afford some evidence which favours the Ethiopian expedition. The cartouche of Psammetichus II is engraved in large characters and conspicuously on several rocks in the region of the First Cataract. His short reign is very notable for the abundance of fine work in hard stone. He may then have visited the granite quarries of Syene merely as a patron of the arts. But there is also the famous series of inscriptions in Phoenician, Carian, and Greek upon the leg of one of the colossi at Abusimbel, 170 miles south of the First Cataract, the most important of which states, ' When king Psamatikhos had come to Elephantine this was written by those who sailed with Psammatikhos (sic) the son of Theokles. They went above Kerkis as far as the river permitted. Potasimto was leader of the foreigners and Amasis of the Egyptians. Arkhon son of Amoibikhos and Pelekos son of Eudamos wrote me.' Another graffito states, `[I came here] with Psameitikhos when the king made his first expedition Evidently this was an armed force sent by the Pharaoh : but it is still an open question to which of the kings named Psammetichus it is to be referred. The name Psammetichus may have been adopted by an adult, more especially if he was a foreigner, in honour of the king whom he served, and in the long reign of Psammetichus I there was time for new generations to grow up bearing his name ; but the words `the first expedition' are in favour of an early date in the reign. The only other significant name is Amasis [570–526 BC] (Ahmosi), which was very common in and after the reign of Amasis II at the end of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. It is common also in the Eighteenth Dynasty, but rare in the interval. So far this name, therefore, would point to the reign of Psammetichus III, who may have had occasion to visit the Nubian frontier in his reign of six months before meeting the invading host of Cambyses. Psammetichus I also appears to have sent an expedition into Nubia (see above, p. 73). But altogether the balance of evidence seems to be in favour of the expedition having taken place under Psammetichus II 2 palaeographical considerations alone being almost conclusive against an attribution to Psammetichus III in 525 B.C." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

7. "With regard to Phoenicia, &c., there seems no reason why Psammetichus II should not have made an expedition in that direction to renew the contest for it with the prevailing power in Mesopotamia. Assurbanipal, after his triumph over the Ethiopian Tandamane in Egypt (661 B. c. or earlier), besieged Tyre, and, without capturing it, compelled it to pay tribute. Thenceforward he seems to have paid little attention to the west, though Syria and Egypt were long considered officially as provinces of the Assyrian empire. For many years Assurbanipal was engaged eastward in wars and in crushing revolts in Elam, Babylonia, and Arabia, with unvarying success. From the Assyrian records we learn that certain correspondence of Pisamilki or Tusamilki (Psammetichus I) with Gugu (Gyges) the king of Lydia was regarded as treasonable ; but probably no trace of real suzerainty over Egypt then remained. The drain of constant war had told fearfully . on the fighting population of Assyria, and in the later years of Assurbanipal hordes of Scythians overran his empire. Herodotus tells us that Psammetichus I turned back the Scythians from the frontier of Egypt by gifts and entreaties3, and that he took Azotus after a siege of twenty-nine years 4. Of Neco's bold bid for Syria we have more certain evidence. In or about 6o8 B. c. Pharaoh-Necoh slew Josiah king of Jerusalem at Megiddo, and penetrated to Carchemish on the Euphrates 1, driving any remnants of Assyrian domination before him : returning thence he deposed Jehoahaz, who had succeeded his father Josiah at Jerusalem, after three months' reign, placed his brother Eliakim (Jehoiakim) on the throne, and put the land of Judah under tribute 2. Herodotus, too, says that Neco's defeated the (As)Syrians at Magdola, by which he means Megiddo, and took Cadytes, which may be Gaza or some city in northern Syria. For a few years Neco's power must have been supreme in Syria, but meanwhile the Babylonian kingdom had become firmly established in the hands of Nabopalassar, whose son Nebuchadrezzar was ever pushing towards the Euphrates to win from the Scythians and the Egyptians the empire that the Assyrians had lost ; and soon after we are told that ' the king of Egypt came not into the land any more, for the king of Babylon had taken, from the brook of Egypt unto the river Euphrates, all that pertained to the king of Egypt The book of Jeremiah 4 and Josephus 5 place the decisive battle at Carchemish, and represent the Egyptian forces as led by Neco's himself. Berosus represents the cause of Nebuchadrezzar's expedition as the rebellion of the `satrap' in charge of Egypt, Syria, and Phoenicia : if this is not a sheer mistake it shows that the old view of the Egyptian Pharaoh as a tributary prince had been perpetuated from the time of the Assyrian domination, The date of the Babylonian expedition is about 605 or 604 B. C. It is by no means certain that Nebuchadrezzar obtained a hold on Phoenicia at this time. Josephus preserves a fragment of annals, according to which the almost impregnable fortress of Tyre, under its king Ithobal, was besieged by Nebuchadrezzar for thirteen years ; but this was probably about 585-57o, in the reign of Apries of Egypt. In the meanwhile, for all we know, Phoenicia may have been under Egyptian suzerainty7. At any rate, the Pharaohs could intrigue and send expeditions, as Apries (Hophra) undoubtedly did ; there is, therefore, nothing inherently improbable in the idea of an expedition to Phoenicia or Syria under Psammetichus II. The conquest of Jerusalem took place in the 1.9th year of Nebuchadrezzar's, i. e. in 586 B. C. : the year to which this would correspond in Egyptian annals could scarcely be earlier than the first or second of Hophra (Apries). The siege began a year and a half before this ', and was interrupted at one time by the approach of Pharaoh's army in. This event would hardly fall in the 4th year of Psammetichus II, but rather belongs to the reign of Apries. Herodotus " tells us that Apries marched by land to attack Sidon, and fought the king of Tyre by sea. It would now seem that each Pharaoh, from Psammetichus I to Apries, warred in Syria. The capture of Gaza by Pharaoh, referred to in a heading to one of Jeremiah's prophecies 12, cannot be identified with certainty, and the authenticity of the heading is thought to be very doubtful." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

8. "Psammetichus II reigned 5 1/2 years, ascending the throne between the 7th of Paophi and the 9th of Epiphi (WIEDEMANN, Geschichte Aeg. v. Psamm. I, p. 119). He died on the 23rd of Thoth of his 7th year (Ann. du Service, v. p. 86), so that more than two full years elapsed between the announcement of the expedition into Syria in his 4th year and his death. That his death took place now is shown by the statement (16/1) that Ptahatfi received the stipend from the first year of his successor Apries, and the same statement makes it probable that the appointment of Ptahatfi by the priests (and consequently the expedition to the land of Khor to which Peteesi was attached) befell at the end of the reign. The announcement of the intended expedition may have been towards the end of the 4th year, the expedition itself may have lasted into the 6th year. In any case the death of the king seems to have taken place soon after Peteesi returned, probably still accompanying the expedition." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

9. "At the time of the New Kingdom Khor was the name of south-western Palestine, but it obtained a more extended meaning: see W. MAX 'MULLER, Asien und Europa nach altagyptischen Denkmalern, pp. 148-56. In the decree of Canopus of the reign of Ptolemy Euergetes, when the Egyptian Empire extended far into Western Asia, [x] is rendered in demotic the province of the Amor,' (ibid., p. 2 1 9), and [x] `the province of the Khor (or Khors ?)' (see also additional notes). If the plural is correct in the latter case it may refer to the different cities or portions constituting Phoenicia. Hence the land of Khor' probably means the trading coastland of Phoenicia, though it may also include other and less wealthy and important parts of Syria which are distinguished as the province of (the) Amor in the decree of Canopus. In the Demotic Prophecies' the land of Khor' is mentioned as the rival of Egypt, which might refer to any event from the time of Esarhaddon to Antigonus, and in the third century A. D. (Pap. Mag. L. L., xxi. 34) apparently as a source of wine symbolized by the blood of wild a wild boar; cf. Hdt. iii. 6.." (The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD)

III. Authorities on Papyrus xxx:

- "In 591 Psammetichus II (594–588) made a trip through Ḫurru (Phoenicia), which may have had as its purpose the inciting of further rebellion in Palestine." (ABC, Volume 4, Page 1043)

- "There is evidence for military cooperation between Egypt and Judah in 593, and the following year Psammetichus II organized a triumphal visit to Palestine (Greenberg Ezekiel 1–20 AB, 13)." (ABD, Zedekiah)

- “It is significant of the political basis of Zedekiah’s initiative that just at this time evidence exists for military cooperation between Judah and Egypt. Psammetichus II won a victory in Nubia in 593 with the help of Judean troops (Letter of Aristeas, 3; Freedy-Redford, p. 476). Following up this victory, Psammetichus organized a triumphal visit to Phoenicia-Palestine in 592, which cannot but have strengthened the hands of the anti-Babylonian forces in that region (W. Helck, Geschichte des alten Ägypten, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968, p. 254; Freedy-Redford, p. 471). Whether Zedekiah’s revolt is to be connected with that visit (Freedy-Redford, p. 480, fn. 100), or only with the accession of Pharaoh Hophra in early 589 (A. Malamat, The World History of the Jewish People, The Age of the Monarchies, IV/1 [Jerusalem: Massada, 1981], p. 215), preparations for the revolt, especially the acquisition of chariotry and auxiliaries from Egypt (cf. Ezek 17:15) must have antedated it considerably." (Ezekiel 1-20, Moshe Greenburg, p 13, 2008 AD)

Nubian/Ethiopian military campaign of Psammetichus II in 593 BC

"Thinking that the time had come to press the demand, which I had often laid before Sosibius of Tarentum and Andreas, the chief of the bodyguard, for the emancipation of the Jews who had been transported from Judea by the king’s father—for when by a combination of good fortune and courage he had brought his attack on the whole district of Coele-Syria and Phoenicia to a successful issue, in the process of terrorising the country into subjection, he transported some of his foes and others he reduced to captivity. The number of those whom he transported from the country of the Jews to Egypt amounted to no less than a hundred thousand. 13 Of these he armed thirty thousand picked men and settled them in garrisons in the country districts. (And even before this time large numbers of Jews had come into Egypt with the Persian, and in an earlier period still others had been sent to Egypt to help Psammetichus II in his campaign against the king of the Ethiopians. But these were nothing like so numerous as the captives whom Ptolemy the son of Lagus transported.)" (Letter of Aristeas 12-13, Pseudepigrapha of Greek Court-official 278-270 BC. Actual: Written by Jew in 150 BC)

"It was from this time that mercenaries began to play a significant role in the country, later forming a separate division in the Egyptian army, a fact known from texts dealing with Psammetichus II’s campaign into Nubia (see below). Garrisons were established at the south in Elephantine, and to the northeast at Daphnae. A local war with the Libyans ended successfully for Psammetichus, and he erected a series of stelae commemorating his army’s victory over these perennial foes in regnal years 10–11 (Goedicke 1962; Basta 1968; Kitchen 1973: 405). In this case, it is clear that the Libyans actually represented Egypt’s western neighbors, rather than the former kinglets of the Delta. It is possible that a third garrison was founded on the west soon after this victory. All three were built to control the entrances into the land, since Egypt had to fear invasion from Kush (south of Elephantine), Assyria (northeast at Daphnae), and Libya (northwest at Marea). In addition, the Nile itself was supplied with an independent fleet, a forerunner of the navy developed in the East Mediterranean by later Saite monarchs. Finally, Psammetichus allied himself to the Lydians who, under King Gyges, began to expand and form a kingdom hostile to the Assyrians (Spalinger 1978c; Millard 1979). Internally, Egypt lost much of the character of the preceding age. The ubiquitous donation stelae were still erected but now under only one king. Local independence in the north had ended by year 8 of the pharaoh and even though Libyan families still held power in some cities, their might was now subservient to the monarch. Initially, Psammetichus stressed the importance of the powerful families in Egypt, such as the Masters of Shipping at Heracleopolis and the Theban dignitaries (Kitchen 1973: 402–3). Later, he placed his adherents, most of whom came from the north, in key positions in the land (Kees 1935). However no real administrative reform took place. The local administrative units, the nomes, became tax collectors’ districts, and outmoded titles dating back to the Old and Middle Kingdoms were employed, but no major reorganization of the finances or bureaucracy was apparently needed. By simply sending his new officials to the south, Psammetichus ran the land effectively." (ABD, Egypt, Volume 2, p 360)

"The Jewish community at Elephantine was probably founded as a military installation in about 650 B.C.E. during Manasseh’s reign. A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus I (664–610 B.C.E.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt. Herodotus reports that in the reign of Psammetichus I, garrisons were posted at Elephantine, Daphnae and Marea. Perhaps as an accommodation to the Jews in Egypt who served as a buffer to renewed Assyrian control of Syro-Palestine (and also to consolidate their loyalty), Psammetichus permitted the Jews to build their temple. The Jews were not the only ones to benefit. The Aramean soldiers on the mainland at Aswan were also allowed to erect temples to their gods—Banit, Bethel, Nabu and the Queen of Heaven. According to the above-cited letter of Jedaniah, the Elephantine temple was constructed sometime before the Persian conquest of Egypt in 525 B.C.E.: “During the days of the kings of Egypt [i.e., when Egypt was independent] our forefathers built that temple in the Elephantine fortress and when Cambyses [the Persian ruler who conquered Egypt in 525 B.C.E.] entered Egypt, he found that temple built.” But the Jews needed more than permission from the Egyptian ruler to build a temple. According to Israelite tradition, foreign soil was impure soil. From Joshua to the prophets to the Babylonian exiles, it was understood that cultic activities should not be performed outside the land of Israel. When the cured Aramean leper Naaman wanted to worship YHWH in his homeland, he took with him two mule-loads of Israelite earth (2 Kings 5:15ff)." (Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?, Bezalel Porten, BAR, BAR 21:03, May/June, 1995 AD)

"From this city you make a journey by water equal in distance to that by which you came from Elephantine to the capital city of Ethiopia, and you come to the land of the Deserters. These Deserters are called Asmakh, which translates, in Greek, as “those who stand on the left hand of the king”. [2] These once revolted and joined themselves to the Ethiopians, two hundred and forty thousand Egyptians of fighting age. The reason was as follows. In the reign of Psammetichus I, there were watchposts at Elephantine facing Ethiopia, at Daphnae of Pelusium facing Arabia and Assyria, and at Marea facing Libya. [3] And still in my time the Persians hold these posts as they were held in the days of Psammetichus; there are Persian guards at Elephantine and at Daphnae. Now the Egyptians had been on guard for three years, and no one came to relieve them; so, organizing and making common cause, they revolted from Psammetichus and went to Ethiopia. [4] Psammetichus heard of it and pursued them; and when he overtook them, he asked them in a long speech not to desert their children and wives and the gods of their fathers." (Herodotus, Histories 2.30.1–4)

"Under Psammetichus II (595–589) no change occurred in Egypt’s Asiatic policy. Possibly in order to prevent continued restiveness, Nebuchadnezzar appeared in Hatti both in January and in December of 594, first in order to collect tribute, then with his army (Wiseman, Chronicles, pp. 72–74). Was it during that time, and to show submission, that Zedekiah went to Babylon in his fourth regnal year? (See note 5 to Table of Dates.) But restiveness continued, and in that year Zedekiah called a conclave of west-Asiatic states in Jerusalem with a view to throwing off the Babylonian yoke—to judge from Jeremiah’s symbolic behavior (Jer 27). It is significant of the political basis of Zedekiah’s initiative that just at this time evidence exists for military cooperation between Judah and Egypt. Psammetichus II won a victory in Nubia in 593 with the help of Judean troops (Letter of Aristeas, 3; Freedy-Redford, p. 476). Following up this victory, Psammetichus organized a triumphal visit to Phoenicia-Palestine in 592, which cannot but have strengthened the hands of the anti-Babylonian forces in that region (W. Helck, Geschichte des alten Ägypten, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968, p. 254; Freedy-Redford, p. 471). Whether Zedekiah’s revolt is to be connected with that visit (Freedy-Redford, p. 480, fn. 100), or only with the accession of Pharaoh Hophra in early 589 (A. Malamat, The World History of the Jewish People, The Age of the Monarchies, IV/1 [Jerusalem: Massada, 1981], p. 215), preparations for the revolt, especially the acquisition of chariotry and auxiliaries from Egypt (cf. Ezek 17:15) must have antedated it considerably." (AYBC, Ezekiel 1–20, p 12)

The Expedition of Psammetichus II, Catalogue of the Demotic Papyri in the John Rylands library, F. Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, Papyrus IX, Column 14, line 16 - Column 16, line 1, 1909 AD

"The historical framework of the book [Nehemiah] is confirmed by papyri which were discovered between 1898 and 1908 in Elephantine, the name of an island in the upper Nile. Here Psammetichus II (593–588 b.c.) established a Jewish colony. The Elephantine papyri are well preserved, written in Aramaic, and are the 5th-century b.c. literary remains of this Jewish colony of the Persian period." (Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, p 1537, 1988 AD)

"Most scholars who have analyzed the letter have concluded that the author cannot have been the man he represented himself to be but was a Jew who wrote a fictitious account in order to enhance the importance of the Hebrew Scriptures by suggesting that a pagan king had recognized their significance and therefore arranged for their translation into Greek." (The Bible in Translation, Bruce Metzger, p 15, 2001 AD)

"Aristeas wrote the Let. Aris. to his brother Philocrates. He was one of the envoys but no further details are given about him. We can conjecture that he was a Jew living in Alexandria (Pelletier 1962: 56). His familiarity with Jewish worship and way of life is apparent, but his interests were not limited within that area. In one passage (v 16) he seems to associate himself with those who also call God the Creator “Zeus,” i.e., Greeks or Hellenists, but this somewhat inconclusive statement is outweighed by his special knowledge of Jerusalem and the temple worship (vv 83–118). This would indicate that Aristeas was probably a Jew. It is tempting to conclude from the setting of Let. Aris. that its author likewise came from Alexandria, but this is conjectural. The reference to the Egyptian King Ptolemy Philadelphus (285–247 b.c.) and the use by Josephus (a.d. 37–?110) of Let. Aris. as a source (Jewish Antiquities 12.2.118) provide broad indications of the date. Within these limits the suggested dates, as summarized by Jellicoe (1968: 48–50) fall into three groups: early, ca. 150–100 b.c., and 1st century b.c. It is less probably a contemporary document—and therefore early—because the Pentateuch seems to be assumed by the author to be a well-established version, the origin of which he describes." (ABD, Letter of Aristeas)

Herodotus: "Psammis [Psammetichus II] reigned over Egypt for only six years; he invaded Ethiopia, and immediately thereafter died, and Apries the son of Psammis reigned in his place." (Herodotus, Hist. 2.160.1)

in an earlier period still [593 BC] Jews had been sent [by Zedekiah] to Egypt to help Psammetichus II in his campaign against the king of the Ethiopians [Nubia]

Timeline:

1. 664 BC : Psammetichus I (Psamtik I) becomes Pharaoh (664-610 BC)

a. "A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus I (664–610 B.C.E.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt. Herodotus reports that in the reign of Psammetichus I, garrisons were posted at Elephantine, Daphnae and Marea. Perhaps as an accommodation to the Jews in Egypt who served as a buffer to renewed Assyrian control of Syro-Palestine (and also to consolidate their loyalty), Psammetichus permitted the Jews to build their temple." (Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?, Bezalel Porten, BAR, BAR 21:03, May/June, 1995 AD)

2. 610 BC : Nico II becomes Pharaoh after Psammetichus I dies (610-605 BC)

3. 595 BC : Pharaoh Nico II dies and Psammetichus II (Psamtik II) becomes Pharaoh (595-589 BC)

4. 593 BC: Psammetichus II defeats Nubia with help of Zedekiah.

a. "The number of those whom he transported from the country of the Jews to Egypt amounted to no less than a hundred thousand. Of these he armed thirty thousand picked men and settled them in garrisons in the country districts. (And even before this time large numbers of Jews had come into Egypt with the Persian, and in an earlier period still [593 BC] others had been sent to Egypt to help Psammetichus II in his campaign against the king of the Ethiopians. But these were nothing like so numerous as the captives whom Ptolemy the son of Lagus transported.)" (Letter of Aristeas 12-13, Pseudepigrapha of Greek Court-official 278-270 BC. Actual: Written by Jew in 150 BC)

b. "It is significant of the political basis of Zedekiah’s initiative that just at this time evidence exists for military cooperation between Judah and Egypt. Psammetichus II won a victory in Nubia in 593 with the help of Judean troops (Letter of Aristeas, 3; Freedy-Redford, p. 476). Following up this victory, Psammetichus organized a triumphal visit to Phoenicia-Palestine in 592, which cannot but have strengthened the hands of the anti-Babylonian forces in that region (W. Helck, Geschichte des alten Ägypten, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968, p. 254; Freedy-Redford, p. 471). Whether Zedekiah’s revolt is to be connected with that visit (Freedy-Redford, p. 480, fn. 100), or only with the accession of Pharaoh Hophra in early 589 (A. Malamat, The World History of the Jewish People, The Age of the Monarchies, IV/1 [Jerusalem: Massada, 1981], p. 215), preparations for the revolt, especially the acquisition of chariotry and auxiliaries from Egypt (cf. Ezek 17:15) must have antedated it considerably." (Ezekiel 1-20, Moshe Greenburg, p 13, 2008 AD)

c. "There is evidence for military cooperation between Egypt and Judah in 593, and the following year Psammetichus II organized a triumphal visit to Palestine (Greenberg Ezekiel 1–20 AB, 13)." (ABD, Zedekiah)

5. 592 BC: Psammetichus II triumphal visit to Zedekiah [Phoenicia-Judea] after defeating Nubia in 593 BC.

a. "In 591 [Actually 592 BC] Psammetichus II (595-589) made a trip through Ḫurru (Phoenicia), which may have had as its purpose the inciting of further rebellion in Palestine [against Nebuchadnezzar]." (ABC, Volume 4, Page 1043)

b. "Following up this victory [Nubia 593 BC], Psammetichus organized a triumphal visit to Phoenicia-Palestine in 592, which cannot but have strengthened the hands of the anti-Babylonian forces in that region (W. Helck, Geschichte des alten Ägypten, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968, p. 254; Freedy-Redford, p. 471). Whether Zedekiah’s revolt is to be connected with that visit (Freedy-Redford, p. 480, fn. 100), or only with the accession of Pharaoh Hophra in early 589 (A. Malamat, The World History of the Jewish People, The Age of the Monarchies, IV/1 [Jerusalem: Massada, 1981], p. 215), preparations for the revolt, especially the acquisition of chariotry and auxiliaries from Egypt (cf. Ezek 17:15) must have antedated it considerably." (Ezekiel 1-20, Moshe Greenburg, p 13, 2008 AD) xxx

6. 592 BC: Pharaoh Psammetichus II one of two eagles of Ezekiel 17:15

a. "But he [Zedekiah] rebelled against him [Nebuchadnezzar/God] by sending his envoys to Egypt [Psammetichus II] that they might give him horses and many troops. Will he succeed? Will he who does such things escape? Can he indeed break the covenant and escape?" (Ezekiel 17:15)

b. On 17 Sept 592, Ezek 8-19: Ezekiel is translated to Jerusalem for the first temple vision. Zedekiah rebels against Babylon: Ezek 17:15; 2 Kgs 24:20 Edom condemned: Ezekiel 16:55-59

c. Pharaoh Psammetichus II (Psamtik II) was the second of two eagles in Ezekiel 17: "But he rebelled against him by sending his envoys to Egypt that they might give him horses and many troops. Will he succeed? Will he who does such things escape? Can he indeed break the covenant and escape?" (Ezekiel 17:15) " (Ezekiel 17:15, 592 BC)

d. "Significantly, the change in Zedekiah’s disposition toward Nebuchadrezzar appears to have coincided with the accession of Psammetichus II 595–589) to the throne of Egypt. A papyrus from El Hibeh refers to a visit by the pharaoh to Syria-Palestine in his fourth year, ostensibly as a religious pilgrimage to Byblos. But such royal visits usually also have political undertones, especially since these states had revolted against Babylon as recently as three years previously. In an early second-century B.C. letter to Philocrates, Aristeas recalls that under Psammetichus, Jews had assisted the Egyptians in their conflicts with the Ethiopians (Ep. Aristeas 13). It is not clear whether Psammetichus II encouraged Zedekiah to revolt again in 588. During the ensuing siege of Jerusalem, the Judeans looked to Psammetichus II’s successor, Apries/Hophra 589–570), for aid (cf. Jer. 37:5–7), but in vain. Egypt stood by and watched the razing of its former ally’s capital without taking up arms in its defense. This brief survey of events leading up to the siege of Jerusalem demonstrates that Zedekiah’s pro-Egyptian policy was not a last-minute strategy of desperation. He had been casting his eyes southward for several years." (NICOT, Ezekiel 17:14–15)

e. "The eagle is a popular figure in the prophets as well as in the apocalyptic writings. In Ezekiel’s allegory of the eagles (Ezek. 17:1–21) a great eagle represents the Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar, and another eagle stands for the Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichus II." (Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, Eagle, 1975 AD)

f. "The allegory in vv 1–10* presupposes the conspiracy of Judah with Egypt and Zedekiah’s defection from Babylonian overlordship implicit in it. Greenberg has put together the accounts which appear to support an intervention of Psammetichus II (594–588) in Palestine. The Babylonian reaction, according to Ezek 17:1–9*, has still not taken place. So we are led to the time before the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem (cf. 24:1f*)." (Hermeneia, Ezekiel 17:1–24, 1979 AD)

g. "Although Ezekiel’s original audience would have immediately understood the allegory, God nevertheless provides an oracular interpretation of it. The first eagle is Nebuchadnezzar, who deported the Israelite king Jehoiachin and Ezekiel’s fellow exiles to Babylon in 597 b.c. Nebuchadnezzar then placed the Davidide Zedekiah on the throne in Jerusalem and made a treaty with him, thus providing all the conditions necessary for political stability in the land. However, Zedekiah rebelled and sought military support for his revolt against the Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichus II, the second eagle of the allegory. Ezekiel, like Jeremiah (Jer. 27:4-15), considered this move not only a political blunder but also a violation of God’s will. Therefore the judgment will take place on two levels. On the human level, Nebuchadnezzar will besiege Jerusalem and deport Zedekiah to Babylon, where he will die. On the divine level, God will trap Zedekiah and judge him by taking him to Babylon, destroying his army in the process (Ezek. 11:11-21). The interpretation of the allegory is straightforward and, for the most part, does not appear to have been crafted after the fall of Jerusalem. In fact Nebuchadnezzar was not able to capture Jerusalem easily (cf. v. 9)." (Harper’s Bible Commentary, Ezekiel 17:11, 1988 AD)

h. "The historical situation outlined in these verses is illuminated by the narrative in Jeremiah 37, which shows that an Egyptian force was apparently sent in the direction of Jerusalem, probably in the summer of 588 bc, in response to Zedekiah’s overtures and that the approach of this army caused a temporary lifting of the siege of Jerusalem which a Babylonian punitive force had already begun in January of the same year (2 Kgs 25:1; Jer. 52:4). We know nothing of the fate of the Egyptians but we can presume that their efforts were unsuccessful, and possibly only half-hearted as well, because the siege was soon renewed for a further year until Jerusalem finally fell in July 587 bc. An interesting cross-reference is to be found in the Lachish letters, a collection of twenty-one ostraca found in the excavated ruins of Lachish (modern Tell ed-Duweir) and including reports sent in to the military governor there from one of his outlying commanders about the progress of the campaign against the Babylonian armies. One of these, datable about 590 bc, supplies the information that ‘Coniah, the son of Elnathan, commander of the army, has gone down on his way to Egypt.’ We are left to surmise the object of his departure, but it may well have been to obtain assistance from Pharaoh Psammetichus II (593–588)." (TOTC, Ezekiel 17:11-21, 1969 AD)

i. "Ezekiel depicts the same event with the eagle to be understood allegorically. The eagle’s carrying off the top shoot of a tree (17:3–4a) represents King Nebuchadrezzar, who removes the Davidic house and King Jehoiachin and exiles the ruling elite to Babylon. In 17:7, Ezekiel uses the image of the eagle for another king, “another great eagle with great wings and much plumage.” This eagle is the Egyptian king, Psammetichus II, who tries to extend his power by inciting Zedekiah to rebel against Babylon. But both eagles, Nebuchadrezzar and Psammetichus, come to nought in God’s purposes (17:22–24). Working in a similar paradigm of imperial powers as agents of God’s judgment who will in turn be judged by God, various prophets also use the image of the eagle to depict aspects of these empires: their power, leaders,31 and impact. In these ten passages, the eagle either depicts an imperial power (Assyria, Babylon, Egypt), or represents an aspect of imperial power. Further, God emerges in Ezek 17:22–24 (cf. 17:3–4) as a supereagle who, after using an imperial power to inflict punishment, now punishes the imperial power and saves the people from Babylon. Six passages explicitly use the eagle to depict God’s salvation from imperial tyrants. God saves from Egypt: “You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself” (Exod 19:4; cf. Deut 32:10–11). God also saves from Babylon (Isa 40:31) and from Moab, which exploits Babylon’s presence to threaten Judah (Jer 30:10, 16 LXX = 49:16, 22). In “out-eagling” these imperial powers, God soars even “among the stars” to destroy Edom (Obad 1:4)." (Journal of Biblical Literature, Volume 122, p 473, 2003 AD)

7. 589 BC : Pharaoh Hophra (Apries) becomes king (589-570 BC) when Psammetichus II dies.

8. 589 BC: Pharaoh Psammetichus II (Psamtik II) II dies shortly after he sends his army to defend Jerusalem (Jeremiah 37:5-7). Hophra may have been the crown prince like Nebuchadnezzar in 605 BC when he was recalled back to Babylon to claim the throne and becomes Pharaoh (589-570 BC) The Babylonians stop the siege of Jerusalem they redirect their attack on Pharaoh's approaching army. (Ezek 29:1-16; 30:20-26; 31:1-18) Hophra either returned to claim the throne after the death of his father or wisely calls the attack off. Zedekiah is now defenseless and vulnerable but still doesn't surrender to Nebuchadnezzar. Nebuchadnezzar's withdrawal of sieging Jerusalem then returning to destroy the city is an anti-typical echo of Titus's withdrawal in 70 AD. The former provided Nebuchadnezzar the opportunity to surrender, sparing the city and the later provided an opportunity for the Christians to escape the city (Lk 21:20) But Nebuchadnezzar will withdraw a second time as we will see, in the Sabbatical year of 588.

9. 588 BC: "Ezekiel never identifies the pharaoh by name, but from Jer. 44:30 we learn that Hophra is in view. At the turn of the century the restrained policy of his predecessor, Psammetichus II, had enabled Nebuchadrezzar to capture Jerusalem unmolested. But Hophra’s foreign policy was opportunistic and ambitious. Responding to Zedekiah’s call for aid, he challenged the Babylonians by sending troops into Palestine, which forced Nebuchadrezzar to lift briefly the siege of Jerusalem. But the efforts proved futile for Zedekiah, as the Egyptians were quickly driven from Judean soil. According to v. 2b the scope of this oracle extends beyond the Egyptian royal house to all Egypt. On the principle of corporate solidarity, v. 2b indicates that the fate of nation is inextricably bound to the fate of the king, though the first phase of the oracle will focus on the pharaoh himself." (NICOT, Ezekiel 29:1-2, 1998 AD, 588 BC)

Conclusion:

- What we read in the book, we find in the ground, or in this case in the Papyrus Pushkin 127 manuscript that dates to 1001 BC.

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.