|

Standardized Architectural Synagogue Signature Typology Architectural Similarities between Ancient Synagogues and the Church Christians borrowed from Jewish synagogues, not the other way around. |

Standardized Architectural Synagogue Signature Typology

Synagogue Architecture adopted by the Christian Church

Floorplans and Furnishings of Pre-70 AD Second Temple Period synagogues

|

Synagogue Architectural Typology incorporated into the Christian Church |

|||

|

Architecture |

Probable Mosaic origin |

Synagogue Typology |

Church Typology |

|

Mikveh (baptistry) |

Tabernacle and Temple Brass was basin for cleansing |

Every synagogue had a nearby Mikveh for full immersion for ritual purity. Many Jews became Christians in their synagogue Mikvehs. |

Mark 16:16; Acts 2:38; 22:16; 1 Pe 3:21 Ritual purity by washing away sins through the blood of Christ in obedience to the great commission: Mt 28:18-19. |

|

Freestanding columns |

Solomon’s temple freestanding pillars: Jachin and Boaz |

Freestanding columns at Herodium and Magdala |

Antitype of Individual Christians and the Church as a Pillar of Truth |

|

Bema (raised area) |

Ezra’s platform on top of which he read the Law (Torah) Nehemiah 8:4 |

Raised are in center where the reader or speaker would stand |

Prototype of the Pulpit: Raised area at front where preacher stands |

|

Synagogue perimeter bench seating |

None |

Center focused benches lining the perimeter of the assembly room. |

Metaphor for our equality in Christ. |

|

Moses Seat (government) |

Moses authority |

Privilege, preference, being first, special recognition. |

Metaphor for pride. Replaced by Christ: Deut 18:18 |

|

Niches and Ark of the Scroll (storage) |

“Ark of Covenant” inside was the ten commandments on the side was the Torah |

“Ark of the Scrolls” wooden cart, cabinet sometimes placed in a niche in a outside wall. |

Architectural Prototype of the Church Apse |

|

Table of the Scrolls |

Table of shewbread |

Stone or wooden table scroll were placed upon during worship services. |

Prototype of the Lord’s supper table |

A. Defining standardized pattern of architectural “synagogue signature typology”

1. The architectural layout/floorplan of early synagogues shows a high degree of similarity, though not identical.

2. “Origin of the Second Temple Synagogues Architectural Plan: Furthermore, based on architectural evidence, Strange (2003:53-57) holds that the seven Temple period synagogues in Israel (Capernaum, Gamla, Herodium, Jericho, Qiryat Sefer, Masada and Modiin) followed a kind of cultural template, consisting of a distinctively Jewish type of basilica inspired by the Second Temple courts. The architectural plan contained columns arranged between the center of the hall and the benches, and might also have contained an ark (though no proof exists). He argues for clerestory roofing above the central hall, which provided light for the hall and benches. He concludes that these structures' "were appropriate for hearing declamation of Torah rather than watching a spectacle." ” (Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research, Rachel Hachlili, p45, 2013 AD)

3. “As the early Christian movement developed a distinctive identity with features that differentiated itself clearly, sometimes aggressively, from its Jewish sibling, it is striking that its architectural practices were at first barely indistinguishable from Judaism's. The use of house-churches and house-synagogues was nearly identical. The gradual alterations were almost identical as a patron's house was adapted to meet the new needs and developing liturgy within the two communities. Whereas Christianity's rhetoric increasingly distinguished between itself and neighboring Jews, Christianity seems to have been strongly tied to the model of the synagogue for indications of how it should develop artistically and functionally. The impact of synagogues on early Christian church buildings has been obscured by the lack of extensive evidence in the crucial period of the late first through late third centuries. In addition to Jews and Christians using similar strategies in the early stages of the development of communal structures—especially the strategy of using houses as the basis for their meetings—it is apparent that both developed in somewhat similar ways in their use of the basilica model as their most common long-term solution. This makes it likely that both followed similar patterns in the processes by which they moved from one to the other. But if this scenario is correct, there is little doubt in my mind that such similarities as there were derived from Christian borrowing from Jewish synagogues, not the other way around.” (Building Jewish in the Roman East, Peter Richardson, p343, 2004 AD)

4. “Almost all buildings identified as synagogues in Israel exhibit a kind of standard plan. This plan is so regular that it virtually amounts to a signature for its function. The regular plan also reveals intentionality on the part of the builders. In this template, derived from examination of the putative synagogue buildings listed above, the builders marked interior floor space by walkways on three or all four walls with benches between the walls and the columniation. The result of such a design is that participants had to look between the columns to see what was going on. Although this feature is known from Nabatean mortuary temples, it is otherwise virtually unknown in the Roman world.” (The Ancient Synagogue from its origins to 200 CE, Birger Olsson, Archeology and ancient synagogues, James F. Strange, p39, 2003 AD)

5. Pre- 70 AD synagogue typology is like “modern house typology”: Synagogue signature typology is about function on blueprints:

a. There are thousands of different looking house blueprints, but they all have a kitchen, bedroom, bathroom, living room and storage area.

b. In the same way pre-70 AD synagogue typology is not the pattern of how the columns are placed, but simply that each synagogue had columns.

c. When you walk into a house, you are less concerned with where the walls are as long as it has a Bedroom, bathroom and kitchen etc.

6. In the same way the earliest synagogue top plans (construction blue prints) have variation but they all have benches, columns and a bema.

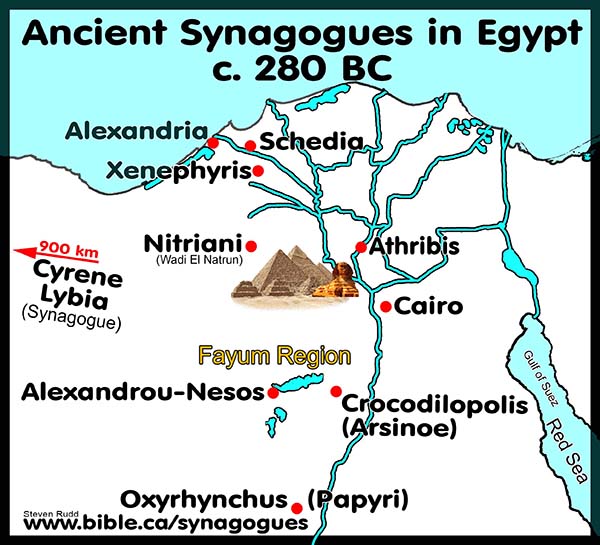

a. Variations in size and shape of meeting hall. From almost square (Magdala) to rectangular (Capernaum). From small (Migdal and Magdala) to large (Sardi, Alexandria, Capernaum). The Great second temple period basilica synagogue at Alexandria was so large that it was reported to be able to contain TWICE the exodus route population: 3.5 million x 2 = 7 million. This was a common rabbinic figure of speech so the statement is of no help in determining the exodus route population.

b. Variations in number and location of entrances: 1-3 different entrances located randomly on any of the four walls. At Delos there were three entrances from the south and one from the east (this refers to the second stage of the building; in the first stage there were three entrances from the east). At Herodium there were three entrances from the east. However, at Masada there was only one entrance to the east, and at Gamla there was a main entrance from the southwest and a side entrance from the east.

7. Synagogue floorplans were following a template that archeologists today can easily recognize if enough of the elements are present.

a. “Synagogue buildings were generally erected on a high place in a city or village, in the centre of the town, or near a water source. ” (Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research, Rachel Hachlili, p5, 2013 AD)

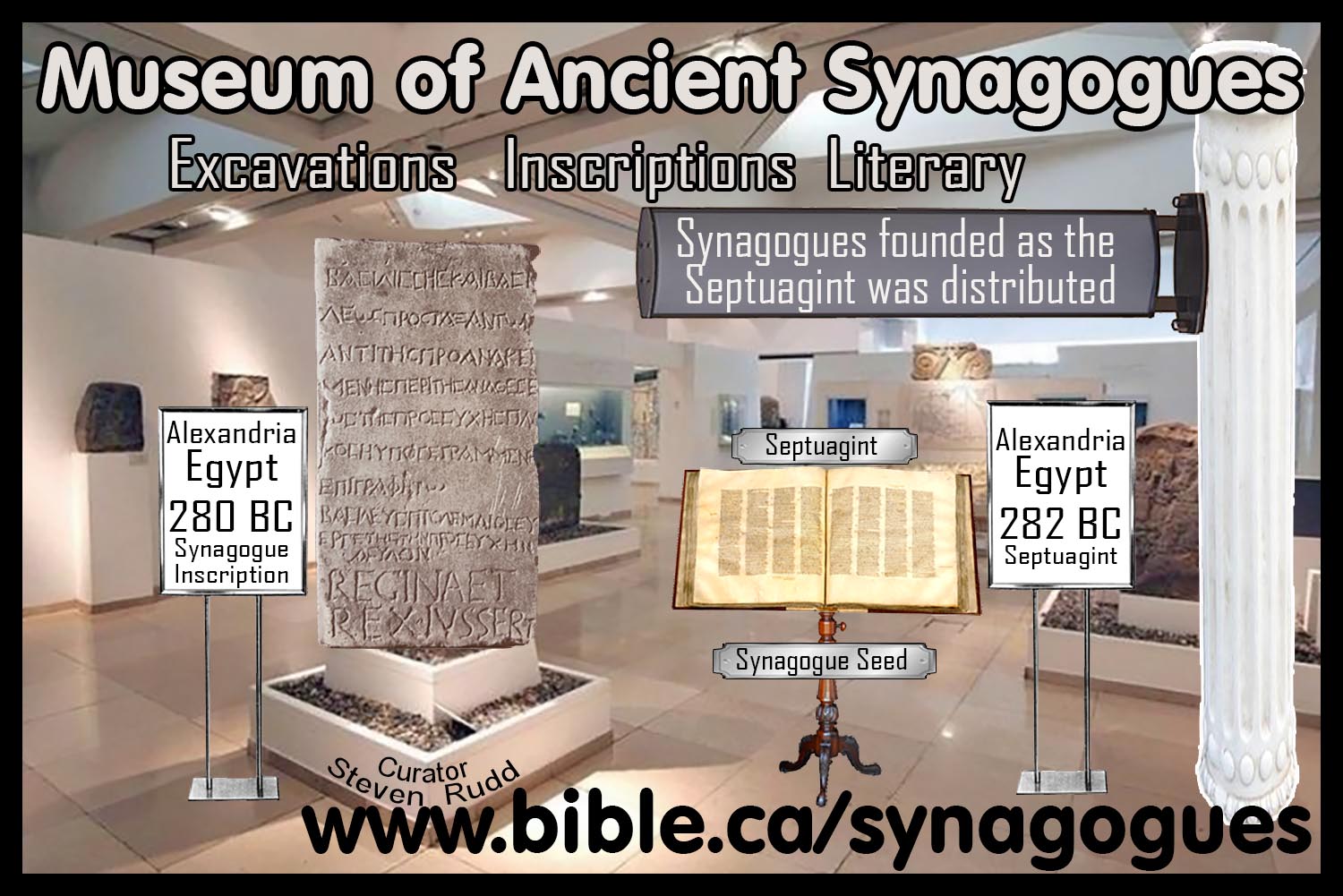

B. The standardized pattern of architectural “synagogue signature typology”: 280 BC - 70 AD:

1. A room

2. Columns

a. Four or more living the perimeter close to the benches

b. sometimes freestanding: Freestanding columns probably echoed the symbolism of the two freestanding columns in Solomon’s temple.

c. The great basilica synagogue at Alexandria had two rose of columns, one within the other.

3. Perimeter benches lining two to four walls each with one to six rows.

4. A bema (raised area) for the officiate who read the Bible, taught the lesson or addressed the crowd. (The synagogue bema probably echoes Ezra’s wooden platform.) Nehemiah 8:4

5. Moses Seat for the synagogue official

6. Mikveh (baptistry)

7. A scroll storage area: architectural niche in which a wooden cabinet, sometimes with doors and sometimes without doors often with curtains.

8. A scroll table: Wooden or stone (Magdala)

9. NOT pointing to Jerusalem:

a. If an archeologist excavates a synagogue the first thing he can do to determine if it is pre-70 or not is to take a compass bearing in relationship with Jerusalem: If it is oriented towards Jerusalem, it is not a second temple synagogue but likely dates to 200 AD or later.

b. Early synagogue seating was non-directional because the emphasis was on each participant sharing equally with each other.

c. Second generation synagogues (post 70 AD) generally pointed towards Jerusalem.

C. Orientation, Location, size and entrances into ancient synagogues:

1. Not a single pre-70 AD synagogue was facing east or oriented towards Jerusalem.

a. Only after about 100-200 AD did synagogues begin to take special care to be facing Jerusalem.

b. See detailed section below.

2. Variations in physical location and setting:

a. Each of synagogues was built in a different setting.

b. The Delos synagogue had formerly been a private home near the sea, and at Gamla the synagogue was located in the one large public building of the city (at least of those heretofore excavated) near the city wall.

c. A synagogues was built into a Herodian complex where a the dining area (triclinium) of the king's palace atop the mountain was modified by the first Jewish war Zealot rebels into a synagogue complete with freestanding columns, just to make it “feel right”.

d. At Masada an ancient synagogue that was founded by the Maccabees had been converted into a reception hall of king Herod, only to be renovated back into a synagogue by the rebel Jews in 66 AD.

3. Variations in size and shape of synagogue meeting hall:

a. From almost square (Magdala) to rectangular (Capernaum).

b. From small (Migdal and Magdala) to large (Sardi, Alexandria, Capernaum)

c. The Great second temple period basilica synagogue at Alexandria was so large that it was reported to be able to contain TWICE the exodus route population: 3.5 million x 2 = 7 million. This was a common rabbinic figure of speech so the statement is of no help in determining the exodus route population.

d. At Masada an additional storeroom protruded into the sanctuary area.

4. Variations in number and location of entrances:

a. 1-3 different entrances located randomly on any of the four walls.

b. At Delos there were three entrances from the south and one from the east (this refers to the second stage of the building; in the first stage there were three entrances from the east).

c. At Herodium there were three entrances from the east.

d. At Masada there was only one entrance to the east

e. At Gamla there was a main entrance from the southwest and a side entrance from the east.

D. Various other theories of the origin of synagogue typology:

1. The origin of many architectural details of synagogue design is a mystery, but it is most likely that each were drawn on some principle of the Old Testament:

a. Many of the specific design elements of the synagogue can be traced back to the Old Testament.

b. The Mikveh for full immersion is not found anywhere in Moasic Judaism but a unique innovation. However, it likely traces back to the Tabernacle and Temple brass wash laver.

c. The benches lining outside walls with columns obscuring the view is also a puzzle. While the columns may be connected with the two freestanding pillars of Solomon’s temple, exactly whey the Jews adopted the synagogue design remains unknown.

d. Churches on the other hand, borrowed synagogue typology wholesale with a few adaptations.

2. REJECTED THEORY: Synagogues architecturally borrowed from Pagan temples: Jews simply would not adopt a floor plan of a pagan temple so this must be rejected outright.

3. REJECTED THEORY: Synagogues architecturally borrowed from Roman basilicas: None of the pre-70 AD synagogues were basilicas so this must be rejected.

a. Roman basilicas were simple public buildings of any shape and size, but in time they became standardized into the current pattern we are familiar with.

b. The synagogue at Sardis, though it was founded no later than 49 BC, does have a basilica design, but this is likely a 4th century renovation to the original design.

c. The exceptional case of the great Basilica synagogue of Alexandria was in existence in 41 AD (Philo) This structure may have predated the Roman Empire which only perpetuates the puzzle. However, the basilica design may be a first century AD update or rebuilding of a the ancient synagogue that dates back to the very beginning of synagogues in 280 BC in Alexandria.

4. REJECTED THEORY: Synagogues architecturally borrowed from the Jerusalem temple of Herod:

a. Comment: James Strange correctly notes that early synagogues are unlike anything else in the ancient architectural world. The problem with Strange’s theory that synagogue typology has its origin in the Herodian temple which was built in 18 BC, is that many synagogues predate 18 BC, like Madgala. We may never know what the architectural inspiration was of the ancient synagogue but it is not that important. We do know and recognize the blueprint template when we see it.

b. “Although parts of these buildings resemble structures in the Roman Empire, their total organization is novel. For example, one might consider a Council Chamber (bouleuterion) as a progenitor of this synagogue space." This is because bouleuteria were built with concentric, square ranges of benches for seating and a central, rectangular space, presumably for the leader or speaker. One may also think of a basilica as the natural parent of the synagogue, and many scholars do. The parade example of a basilica as synagogue is found at Sardis, though the synagogue at Meiron is also a fine example." As a matter of fact we cannot help but notice and it occurs many times in the literature that Late Roman and Byzantine synagogues are most commonly identified as basilicas. Late Roman and Byzantine basilica synagogues organize inner space by dividing it into a nave and three aisles by columns (one aisle on either side of the nave and one across the back)." Often the builders placed the principal entrances at the narrow end of the building. Yet neither in a Council Chamber nor in a Roman basilica is one required to stand or sit in the aisles and look between the columns to watch business, a ritual, or a spectacle carried on centrally. Rather, one stands in the nave within the space of the ritual or spectacle in either of these two types of buildings.” (The Ancient Synagogue from its origins to 200 CE, Birger Olsson, Archeology and ancient synagogues, James F. Strange, p42, 2003 AD)

c. “The resemblance of these seven [synagogue] buildings to one another extends to structures in the Diaspora, notably at Sardis, Ostia, and Priene. The commonality between them also suggests strongly that their builders shared a mental template for this space. Another way to put this is that these seven buildings and their successors refer to or stand for something else. The builders knew some structure that was of such enormous social and religious moment that it impressed them with the extraordinary idea of arranging seating between the columns and the walls. The most obvious source of this idea is the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, but specifically, those areas where one expects to hear reading of Torah. This narrows our view to one of the perimeter porticos of mount or one of the interior courts. (The Ancient Synagogue from its origins to 200 CE, Birger Olsson, Archeology and ancient synagogues, James F. Strange, p45, 2003 AD)

d. “Although we know little of benches for seating inside the colonnades on the temple mount, the architectural similarities of the buildings of Capernaum, Masada, Herodium, Jericho, Qiryat Sefer, and Modiin to porches on the Temple Mount strongly suggest that the late Hellenistic to Early Roman synagogue in Israel was a Jewish invention based upon the porches or colonnaded spaces of the Temple. This hypothesis still applies whether these halls were sometimes used for ritual purposes and sometimes for non-ritual purposes, such as community meetings.” (The Ancient Synagogue from its origins to 200 CE, Birger Olsson, Archeology and ancient synagogues, James F. Strange, p46, 2003 AD)

e. “In order to strengthen our case that the synagogues of Judea and Galilee represent a type, we need a contrasting type. Since Judaism and Samaritanism seem to have developed separate paths by the first century, it seems appropriate to examine the case of Samaritan synagogues. We hypothesize that, since Samaritanism is self-consciously separate from the Judaism of the period, their synagogues should follow a different template in all periods.” (The Ancient Synagogue from its origins to 200 CE, Birger Olsson, Archeology and ancient synagogues, James F. Strange, p46, 2003 AD)

By Steve Rudd 2017: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections

|

Jesus your messiah is waiting for you to come home! |

|

|

Why not worship with a first century New Testament church near you, that has the same look and feel as the Jewish Synagogue in your own home town. As a Jew, you will find the transition as easy today as it was for the tens of thousands of your forefathers living in Jerusalem 2000 years ago when they believed in Jesus the Nazarene (the branch) as their messiah. It’s time to come home! |

|

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Go to: Main Ancient Synagogue Start Page