Standardized Architectural Synagogue Signature Typology

Synagogue Architecture adopted by the Christian Church

Floorplans and Furnishings of Pre-70 AD Second Temple Period synagogues

"I write so that you will know how one ought to conduct himself in the

household of God,

which is the church of the living God, the pillar and support of the truth." (1 Timothy 3:15)

"‘He who overcomes, I will make him a pillar in the temple of My God." (Revelation 3:12)

|

B. FREESTANDING COLUMNS: ANTITYPE OF CHRISTIANS: 1 Tim 3:15; Rev 3:12 |

Introduction:

1. “Four Freestanding decorative/symbolic columns”:

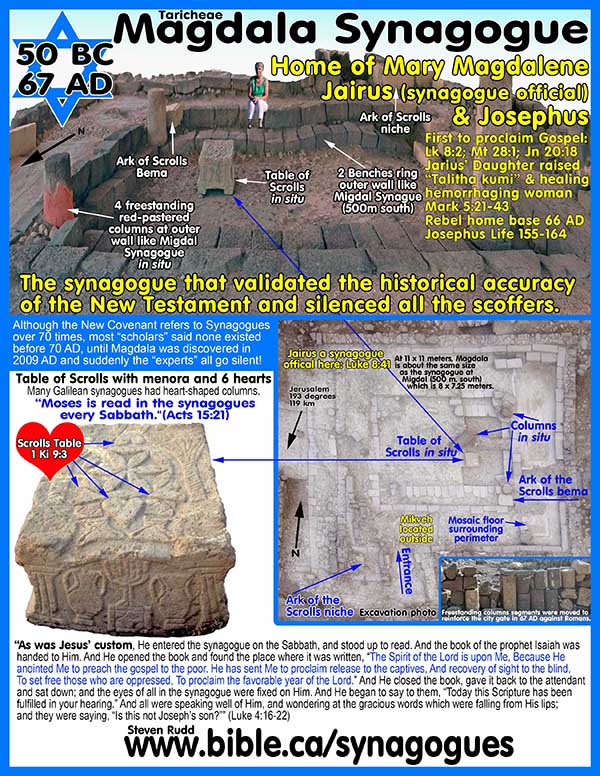

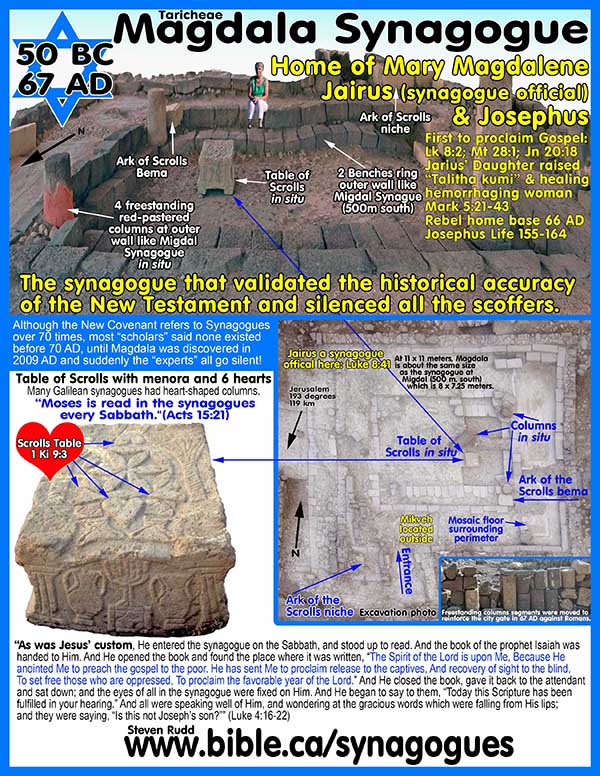

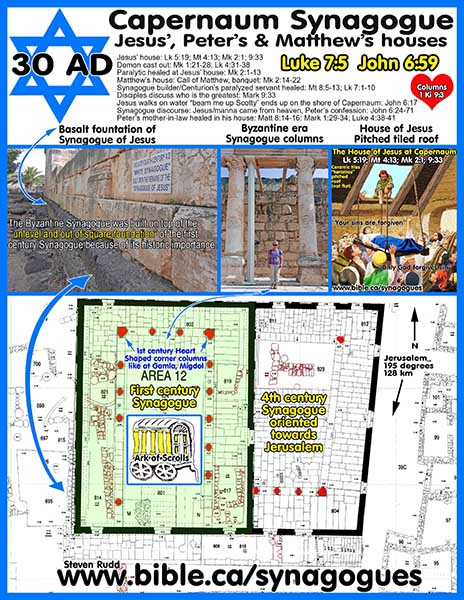

a. Three open air, roofless synagogues utilized four freestanding columns. Magdala 50 BC, Herodium 66 AD, Ostia 50 AD.

b. While the assembly hall at Ostia had a roof, the four freestanding columns were located in an open roofless atrium area: “Besides their essentially functional role, some synagogue columns might have had a purely ornamental purpose. The four monumental columns in the entranceway to the Ostia sanctuary were clearly intended as a kind of propylaeum [entrance of architectural importance to the Synagogue].” (The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, Lee Levine, p340, 1987 AD)

c. There are two roofed synagogues (Magdala 50 BC and Herodium 66 AD) that features four HEART-SHAPED columns in each of the four corners. While the total number of columns was more than four, the special heart shape for the pillars in the corners had symbolic value and were required to conform with “what a synagogue was supposed to look like architecturally.”

2. There are three first temple period synagogues that had “Four Freestanding decorative/symbolic columns”: Magdala, Herodium and Ostia.

a. See top plan for: Magdala 50 BC

b. See top plan for: Herodium 66 AD

c. See top plan for: Ostia 50 AD

3.

Both Magdala

50 BC and Herodium

66 AD have four freestanding columns at the corners of the assembly hall

whereas Ostia

50 BC had four symbolic freestanding columns in the foyer of the synagogue:

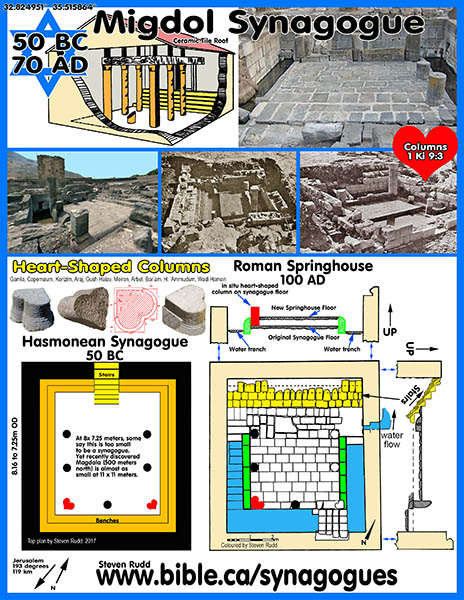

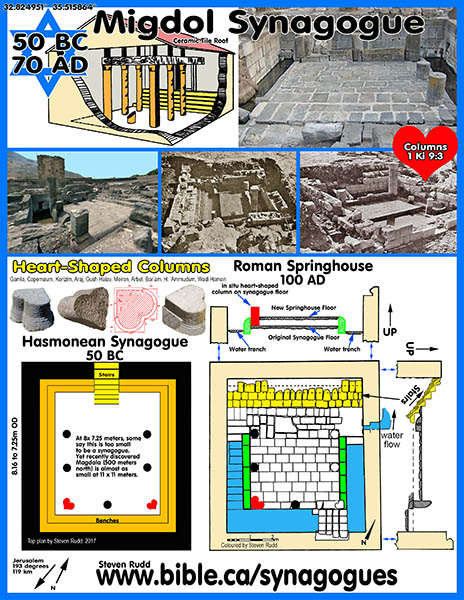

4. The use of heart-shaped symbolic columns in the corners of the synagogues at Gamla 76 BC and Migdol 50 BC further proves this four freestanding columns synagogue typology:

a. See top plan for: Migdol 50 BC

b.

See top plan for: Gamla

76 BC

5. This proves there was a known “synagogue signature typology” that included four freestanding columns.

Discussion:

1. One of the most obvious shared architectural features between synagogues and churches is the presence of two rows of Pillars.

a. In the earliest churches followed the basic synagogue pattern of two rows of columns.

b. While there are many variations on a basic theme, pillars were always used.

c. In ancient Synagogues, pillars were used to execute justice when criminals were tied to pillars and beaten according to Mosaic law.

2. Columns were inscribed and very important architectural features for ancient synagogues:

a. “Columns in synagogues are often noted in literary sources as a place for quiet meditation or for support when feeling ill. In describing someone at the time of prayer, the Yerushalmi states: "Although He far transcends His world, [yet when] someone enters a synagogue and stands behind a column and prays in silence, the Holy One, Blessed be He, hears his prayer." When R. Judah b. Pazi felt weak in the synagogue, he held his head and stood behind a column, whereas in similar circumstances, R. El'azar is reported to have simply left the premises."' In another instance, R. Shmuel bar R. Yitzhaq noticed that the meturgeman leaned against a column and did not stand next to the Torah reader, which he regarded as mandatory."' (The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, Lee Levine, p340, 1987 AD)

b. “Columns to support the roof are an essential element in most public buildings and were found in almost all excavations of ancient synagogues. Donors to the synagogue often inscribed their names and the names of others on these columns as dedicatory inscriptions, as they were readily visible to all, thus affording maximum exposure and recognition. Such columns were found, inter alia, at Dabbura in the Golan and at Gush Halav, Capernaum, and Khirbet Yitztiaqia (south of Bet Shearim). One “Shim'ai, son of Ocsantis”, from Bet Guvrin purchased a column "in honor of the congregation”” (The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, Lee Levine, p340, 1987 AD)

c. “When arriving in Ptolemais [Egypt], named “Rose-bearing” on account of the particular character of the place, in which the fleet waited for them for seven days in accordance with their communal decision, 18 there they celebrated the deliverance with drinking, for the king supplied to them magnanimously all things for their departure to each person till the time when they should arrive at their own homes. 19 And when they had landed in peace, in like manner with appropriate thanksgivings, and there they also established these days to celebrate in good cheer for the time of their sojourning, 20 which events having also devoted to writing on a pillar and dedicating a place of prayer at the site of the banquet, they departed unharmed, free, and overjoyed, having been rescued by both land and sea and river by the command of the king [Ptolemy IV 222-204 BC], each to their 21 previous place. Possessing authority among their enemies, with honor and respect, they were extorted of their possessions by no one at all. 22 And they received back all their things in accordance with the registration, so that those possessing anything of theirs restored it to them with great tribute. The great God perfectly performed magnificent things for their deliverance.” (victory over Ptolemy IV Philopater 222-204 BC persecution; 3 Maccabees 7:17–22, 75 BC)

3. Synagogues were Law courts where the convicted would be tied to a synagogue column and scourged:

a. Mosaic authority for public beatings: “If there is a dispute between men and they go to court, and the judges decide their case, and they justify the righteous and condemn the wicked, then it shall be if the wicked man deserves to be beaten, the judge shall then make him lie down and be beaten in his presence with the number of stripes according to his guilt. “He may beat him forty times but no more, so that he does not beat him with many more stripes than these and your brother is not degraded in your eyes." (Deuteronomy 25:1–3)

b. “A How do they flog him? B One ties his two hands on either side of a pillar [ie synagogue pillars], C and the minister of the community grabs his clothing— D if it is torn, it is torn, and if it is ripped to pieces, it is ripped to pieces— E until he bares his chest. F A stone is set down behind him, on which the minister of the community stands. G And a strap of cowhide is in his hand, doubled and redoubled, with two straps that rise and fall [fastened] to it. 3:13 A Its handle is a handbreadth long and a handbreadth wide, B and its end must reach to his belly button. C And he hits him with a third of the stripes in front and two-thirds behind. D And he does not hit [the victim] while he is either standing or sitting, but bending low, E as it is said, And the judge will cause him to lie down (Dt. 25:2). F And he who hits him hits with one hand, with all his might.” (Mishnah Makot 3:12–13)

c. “Three judges of civil law were in Jerusalem, Admon, Hanan, and Nahum. Said R. Pappa, “Who is the Tannaite authority who repeats, ‘Nahum’? It is R. Nathan, in accord with that which has been taught on Tannaite authority: R. Nathan says, ‘Also Nahum the Mede was among those who make decrees in Jerusalem,’ but sages did not concur with him.” And were there no others? Didn’t R. Phineas say R. Oshayya said, “There were three hundred ninety-four courts in Jerusalem, corresponding to the number of synagogues and the number of schoolhouses and the number of schools for scribes”? There were many more, to be sure, but we make reference in particular to judges of civil law. Said R. Judah said R. Assi, “The civil judges who were in Jerusalem would collect their salary of ninety-nine maneh from Temple funds. If they didn’t find that suitable, they would add to the salary.” “If they didn’t find that suitable”? So are we dealing with money grubbers? Rather: “If they didn’t find that sufficient,” they would give them more, even though they didn’t want it.” (Babylonian Talmud, b. Ketub. 13:1, I.2.A–3.C)

d. “Therefore, behold, I am sending you prophets and wise men and scribes; some of them you will kill and crucify, and some of them you will scourge in your synagogues, and persecute from city to city," (Matthew 23:34)

e. “And I said, ‘Lord, they themselves understand that in one synagogue after another I used to imprison and beat those who believed in You." (Acts 22:19)

4. The only freestanding pillars in the Old Testament are “Jachin and Boaz” in the Solomonic temple.

a. "Thus he set up the pillars at the porch of the nave; and he set up the right pillar and named it Jachin, and he set up the left pillar and named it Boaz." (1 Kings 7:21)

b. "He also made two pillars for the front of the house, thirty-five cubits high, and the capital on the top of each was five cubits. He made chains in the inner sanctuary and placed them on the tops of the pillars; and he made one hundred pomegranates and placed them on the chains. He erected the pillars in front of the temple, one on the right and the other on the left, and named the one on the right Jachin and the one on the left Boaz." (2 Chronicles 3:15–17)

c.

Note: Solomon’s temple as depicted below used ramps, since stairs were

forbidden. The drawing is wrong.

5. KEY POINT that proves synagogue columns were associated with the Temple of Solomon:

a. The Delos Samaritan Synagogue had no columns because they hated the Jerusalem Temple and loved the Mt. Gerizim temple to which they sent annual freewill offerings to support it!

b.

The two inscriptions, the absence of a mikveh and a lack of columns are

evidence this is a Samaritan not Judean Synagogue.

Delos Synagogue top plan WITH NO COLUMNS:

6. Freestanding Synagogue Columns: Exactly what the purpose of these pillars serve or why they exist at all is a mystery.

a. “The Gallery: The existence of upper-story galleries is indicated by columns along the length of the hall, which could have supported such galleries. The U-shaped form of the upper story was dictated by the rows of columns, found on all sides of the hall except for the wall containing the entrances; the galley was constructed as an open gallery above the nave, and would have left the center of the main hall unobstructed. Finds of architectural fragments, as well as smaller columns and capitals which probably formed the colonnade of such a gallery, further corroborate this assumption (Hachlili 1988:194-196). … Further evidence of the existence of galleries is the remains of smaller columns and capitals, which probably formed colonnades; such artifacts have been found at most Galilee and Golan synagogues: Arbel, Beam, Capernaum, H. Shem`a, Nabratein, Korazim, and Golan: Assalieh ed-Dikke, 'En Neshut, Qasrin and at Umm el-Qanatir. Interesting evidence is found in an Aramaic inscription on an architrave fragment from Dabura (Golan), which reads: "Elazar the son of (Ra)bbah made the columns above the arches and beams" (Urman 1972:17, 19; Naveh 1978:no. 7). The inscription apparently refers either to columns of an upper story or to a gallery. The arrangement of columns on three sides of the hall occurs in the Galilean synagogues of Arbel, Bar`am, H. Ammudim, Capernaum, Meiron, Meroth, and at Umm el-Qanatir in the Golan. Some of these galleries were constructed with freestanding columns. In the synagogues of Gush Halav, H. Shern`a, H. Sumaqa, Korazim, and Qasrin, the second story appears to have been structured as a clerestory. ” (Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research, Rachel Hachlili, p151, 2013 AD)

b. “Besides their essentially functional role, some synagogue columns might have had a purely ornamental purpose. The four monumental columns in the entranceway to the Ostia sanctuary were clearly intended as a kind of propylaeum.” (The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, Lee Levine, p340, 1987 AD)

c. While some argue the design is borrowed from Greek or Roman architecture, it is more likely the pillars were somehow symbolic of Solomon’s temple with its two large freestanding pillars out front of the temple.

d. Some believe the Jerusalem Temple of Herod was the inspiration for synagogue columns. But this is unlikely because Herod’s temple was built in 18 BC and Magdala was build no later than 50 BC. Josephus mentions that the court of the women near the Jerusalem temple had pillars and it is likely that this is also true for the Court of Israel and the Court of the Priests even though Josephus is silent about them: “This place was allotted to the women of our own country, and of other countries, provided they were of the same nation, and that equally; the western part of this court had no gate at all, but the wall was built entire on that side; but then the cloisters which were betwixt the gates, extended from the wall inward, before the chambers; for they were supported by very fine and large pillars. These cloisters were single, and, excepting their magnitude, were no way inferior to those of the lower court.” (Josephus, Wars 5.199-200)

e. The only freestanding columns in the bible are the brass columns named Boaz and Jachin.

f. If Boaz and Jachin were not the architype in the back of the mind of the Jews in Egypt when they designed the first synagogues in 280 BC, it is likely the answer will forever elude us.

g. We will proceed under the assumption that Boaz and Jachin were the inspiration of the freestanding columns in synagogues.

7. The synagogues at Magdala and Herodium and Ostia had freestanding “decorative” columns that were added according to known “synagogue typology”.

a.

Both Magdala and Herodium have only four columns at the corners of the

assembly hall.

b. In 66 AD, the Zealots converted an existing OPEN AIR triclinium at Herodium into a synagogue by adding four freestanding columns.

c. Herodium: “When the rebels revolted in the year 66 AD, they were able to capture the Herodium. What did they do? Well, in the place that had been a grand banquet hall in the Herodium, they converted it into a synagogue. Here’s what they did. They of course, fashioned bench seating along the wall, along the walls in a rectangular pattern, and they placed interior pillars—pillars that weren’t necessary, pillars that didn’t hold anything up. Why did they do that? It’s back to what I said in an earlier lecture—this sense of synagogue architectural typology. This is the way a synagogue is supposed to look. If there was this well-known typology, this sense of how a synagogue ought to look—just as many Christians no doubt today would say “This is what a church is supposed to look like”—this argues that the synagogue buildings that we have found (this one admittedly made no earlier than 66 or 67), there was a sense of how they should look. Therefore, the synagogue as a recognizable building has a prehistory, would reach back I would contend not just to the beginning of the first century AD but probably all the way back well into the first century BC. The Herodium is very important evidence, even though the synagogue as such wasn’t very old. After all, the Romans did recapture the Herodium within just a few years. But the way the synagogue was hastily constructed by the rebels, converting a dining hall into a synagogue and following this set pattern would suggest that this pattern or typology was well entrenched in the thinking of the Jewish people in the first century.” (Archeology and the NT, Craig Evans, NT307, Herodium, 2014 AD)

d. I was able to determine that the synagogues at Madgala and Herodium could not structurally support a roof, by simply taking note of the spacing between the four columns was too wide to support anything other than a light canopy covering, if any at all. At Herodium, I noted that the physical distance between the two columns is 8.54 meters (28 Feet) which is too wide for existing building materials to support a proper roof.

e.

In 67 Ad, the Rebels at Magdala, took most of the sections (each column

was composited from several barrel shaped section) of the four synagogue

columns and used them unsuccessfully as a physical reinforcement of the city

gate against the attacking Romans . These synagogue column sections date back

to 50 BC and can be seen today when you visit the site.

8. Archeologists have recognized the structural deficiencies of a roof at Herodium

a. Some solve the structural problem at Herodium by theorizing (without any archeological evidence) that there were 6 columns as Herodium instead of the four they DID find.: Herodium: “The edifice was originally constructed as a triclinium (dining hall) in Herod's fortress palace. Although Corbo has suggested a date during the Bar Kochbah revolt in the second century for the transformation of the edifice, it is more likely that the building was converted for synagogue use around the First Jewish Revolt (so Foerster, Chiat, Binder, Levine, Runesson). Benches line the four walls, and four, possibly six (Corbo; Binder) columns supported the roof and were located between the benches and the open space of the centre of the hall. The rectangular building measures 15.15 x 10.6 m, and a miqweh (2 x 1.5 m) is located just outside the entrance by the northern part of the wall. Identification of this building as a synagogue is based on architectural similarities to other public structures identified as synagogues, e.g., Gamla and Masada (Nos. 10, 28), as well as by the presence of a nearby miqweh.” (The Ancient Synagogue from its Origins to 200 AD, Anders Runesson, 35, 2008 AD)

b. “Herodium: A triclinium at Herodium was converted by the zealots into a hall (15 x 10.5 m) divided by four columns, with benches lined along three walls (Foerster 1981:24; Netzer 2004:14-15). Three entrances were found on the east leading into a large courtyard (Figs. II-lc, 11-4). The hall was covered either by a ceiling, mainly above the benches, or by a light screen cover. The walls were plastered with stucco; a stepped miqveh was found close to the hall. ” (Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research, Rachel Hachlili, p28, 2013 AD)

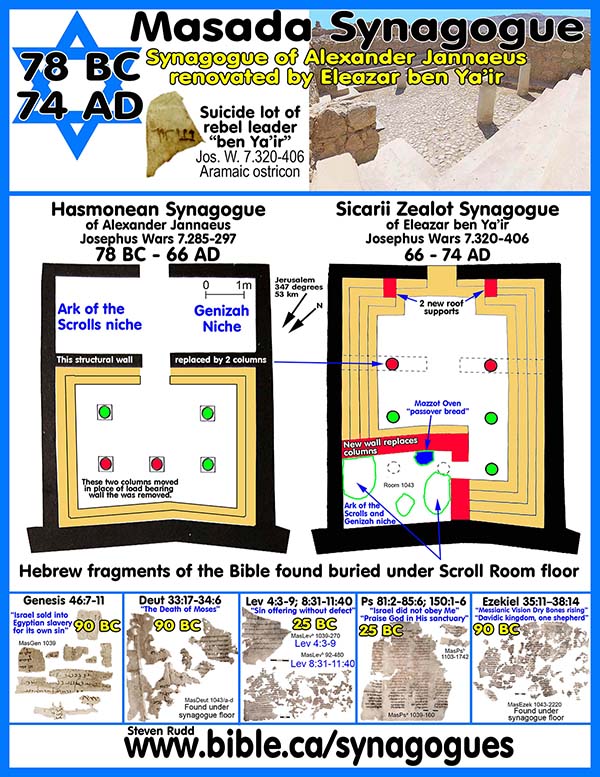

9. The synagogue at Masada did not have freestanding columns because the renovations made by the rebels in 66 AD

a. The architectural graphic overlays the original structure in black and the final structure in red.

b. At Masada, the rebels left three columns in place and moved two others to take up the load form the wall they

c. removed. These were structural and not freestanding. Both Herodium and Magdala synagogues had freestanding

10. Columns in synagogues obscured the view of all the benches:

a. The benches that lined the outside synagogue walls had columns a few feet way from the edge of the bench.

b. As a person walked in the centre or walked on the bema, there would always be someone sitting somewhere, whose view was obstructed by the synagogue pillars.

c. The unique Hebrew design was very different from contemporary Roman Amphitheatres and our modern churches and entertainment theatres where the view of the audience is always clear from each seat… with the exception of Massey Hall in Toronto where you get a discount if you choose as seat behind a support column at the Gordon Lightfoot concert.

d.

The message is more important than the

messenger: The pillars would obscure the view of those seated as they

focus on the central court which indicates the design of the synagogue valued

listening to the reader or speaker, as opposed to seeing him.

JEWISH ART: HEART-SHAPED GALILEAN COLUMNS, HEART SHAPES ON

MOSAIC FLOOR AND TABLES

11.

Heart-shaped “double-columns” columns are found in many of the Galilean synagogues

at Capernaum, Korazim, Gamla, Gush Halav, Migdal, El-Araj, Arbel, Beam, H.

Arnmudim, Meiron and Wadi Hamam.

a. Gush Halav: “The interior was divided into a nave and two aisles by two rows of four columns each. The columns stood on stylobates of dressed ashlars which are parallel to the two north-south walls. Though the pedestals for the columns are virtually identical in form, their dimensions vary. Similarly, the column fragments recovered in the excavations vary in dimension, and the seven capitals recovered differ in style. There are also fragments of two heart-shaped columns with two matching capitals, whose placement within and association with the synagogue is uncertain.” (The question of the synagogue: the problem of typology" in Judaism in Late Antiquity III, Where we Stand: issues and debates in Ancient Judaism, Jodi Magness, Vol 4, Neusner, p1-48, 2001 AD)

b.

Heart-shaped columns are common in ancient synagogues:

Here are five heart column sections from Herod’s palace at Alexandrium. Photo

by Melody Bogle

c.

12 Ancient Synagogue Heart-shaped Column sectionals in secondary use as

patio stones can be seen today on the north shore of the Sea of Galilee on the

beech at the Church of the Primacy of St. Peter: “Below the

steps, sometimes under water if the lake level is high, are six heart-shaped

stones. They are double-column blocks designed for the angle of a colonnade,

and never served any practical purpose in their present position. Known as the

Twelve Thrones and first mentioned in a text of AD 808, they were probably

taken from disused buildings [Synagogues] and placed there to commemorate the

Twelve Apostles. It takes little insight to appreciate the mental jump from

John 21:9 … to ‘You will eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and you will

sit on thrones to judge the twelve tribes of Israel’ (Luke 22:30).” (Holy Land, Murphy O’Connor, p. 319)

d.

Heart-shapes are found on the stone Table of the Scrolls at Magdala and

on the mosaic floor at Jericho which features the Wooden Ark of the Scrolls

cabinet.

e. “Excavations at Magdala [Migdal, not the newly discovered site on the sea of Gailiee] were conducted from 1971 through 1973. These excavations revealed a small building that is surely a small, undecorated synagogue, about 26.8 by 23.8 feet. It was provided with interior columnation around three sides and a set of five benches against the N wall. “Heart-shaped” or double columns stood at the corners of the lines of columnation.” (ABD, Magdala, 1992 AD)

f. Scholars still debate the meaning of several objects on the top of the Magdala Stone (see image below). For example, opinions differ about the interpretation of two clusters of three hearts—six hearts in total. Are they pretty space fillers? Are they ivy leaves? Are they bread loaves? Motti Aviam, Professor of Archaeology at Kinneret College on the Sea of Galilee, interprets these as bread loaves that were offered on the shewbread table. Splitting each heart in half conjures up an image paralleling the way bread was offered on the shewbread table: two sets of six bread loaves. The symbols representing the shewbread tables look like upside-down cups. Finding this symbol on ancient coins gives credence to this interpretation. BAR

g. “Double (Heart-Shaped) Corner Column: The double (heart-shaped) corner column (Fig. IV-21) is another exceptional feature of synagogue architecture, found at the rear corner of the row of columnation and the transverse row. These columns are found in many of the Galilean synagogues: Arbel, Beam, H. Arnmudim, Capernaum, Meiron and Wadi Hamam. At Gush Halav the use and location of the double columns are not clear; three suggestions for their location are presented in Period II—IV: either as the terminal columns on the floor or gallery level or as having been brought to the site in the early Arab period and not having been a part of the original building. A third possibility is suggested by Kohl and Watzinger, who placed them in the corner columns of the back (horizontal) row, which would have created a mezzanine level, and this is the preferred interpretation (Belkin 1990:104-112, Figs. 37-42). The use of the double columns appears to be a continuation of similar corner columns in buildings of the Second Temple period (Gamla synagogue, Migdal I, Fig. II-le). At Korazim, parts of a capital and drum of a double column, belonging to the upper series columns, were found (Yeivin 2000:*20, Fig. 49, 52, Pl. 19:2, 20:1). Another feature peculiar to synagogue architecture is the unusual colonettes flanking the windows, found in Galilean and Golan synagogues. These colonettes, fluted and surmounted by small Corinthian capitals, are found at Arbel, Capernaum, and ed-Dikke (Kohl and Watzinger 1916:Figs. 8, 133, 232, 262). Remains of capitals found in synagogues prove that though the Jews used Roman, and later Byzantine, decorated capitals, local artists were also working in an original style, as witnessed by the added motifs and the special decoration of some of the Ionic and Corinthian capitals. This is evident in all aspects of synagogue architectural decoration. ” (Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research, Rachel Hachlili, p149, 2013 AD)

12. Decoding the ancient Jewish symbolic meaning behind the graphical Heart shaped symbol:

a. Granted the earliest documentation for our modern heart symbol is 11th century AD, it is possible it was also used by the early Jews.

b. If this is true, then the symbolism for the heart in synagogues (House of PRAYER) would be this: "The Lord said to him, “I have heard your prayer and your supplication, which you have made before Me; I have consecrated this house which you have built by putting My name there forever, and My eyes and My heart will be there perpetually." (1 Kings 9:3)

a. a. c. “So now we must answer how all of this is related to the heart. Here is where our lameds are once again defined. At this point it is important to think again about the symbol of the heart and to question its origin. And so it should come as no surprise that the meaning of this symbol will once again be found in the word for “heart” itself. In Hebrew, the word for heart is lev, which is spelled lamed-beit. Rabbi Abraham Abulafia, in the year 1291, wrote a manuscript by the name of Imrei Shefer, in which he defines the meaning of the heart. Rabbi Abulafia teaches that the word lev, lamed–beit, needs to be understood as two lameds. This is because the letter beit is the second letter in the alphabet, and is numerically equivalent to two. So he explains that the word needs to be read and understood as “two lameds.” But it is not enough to have two lameds. As Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh explains, in order for their to be a relationship, the two lameds need to be connected. They need to be face to face. When we turn around the second lamed to face the first, we form the image of the Jewish Heart (as seen in the picture at the beginning of this article). While the heart, as we are used to seeing it, is quite clear in this form, an entirely new part of the heart is also revealed. The heart and the love it represents can thrive, can flourish, only when there is a totality in connection.This is because the letter lamed is the tallest of all the letters in the Hebrew alphabet. The reason is because the lamed represents the concept of breaking out of boundaries, of going beyond your potential, of entering the superconscious from the conscious. The lamed also means two things simultaneously. It means both “to learn” and “to teach,” which shows us that the two are intertwined and both are essential. In a relationship, I must be willing to learn from the other, thereby making myself a receiver. Yet the other person also must be able to learn from me, which then makes me the teacher, the giver. Furthermore, the image of the lamed can be broken down into three other letters. The top part of the letter is that of a yud, the smallest of the Hebrew letters, and the letter that represents the head. The head contains the mind, the intellect, and also the face. The next letter in “Elul” is a vav. In Hebrew, the vav serves as a conjuctive “and.” As a word, vav means “hook,” and in its form it looks like a hook. So in this case the vav is the hook which is connecting the yud, the mind, with the bottom letter, the chaf, which represents the body. Physically speaking, it symbolizes the neck, which transports the flow of blood from the brain to the heart. This teaches us that the heart, that the love that it represents, can thrive, can flourish, only when there is a totality in connection. The Jewish heart, true love, represents a mind-to-mind, face-to-face, eye-to-eye, body-to-body, soul-to-soul connection. The vav, the connection between the head and the heart, must always stay healthy, with a clear flow. If anything cuts it off, the relationship cannot continue. As we all know, one of the quickest ways to kill a person is a slit right across the neck. The neck is our lifeline. It ensures that our head, our intellect, rules above our emotions, and that there is a healthy interchange between the mind and the heart. The heart that we are all familiar with, the symbol that represents love throughout the world, lacks the yud and the vav; it is missing the mind and the neck. The popular symbol represents only the physical connection between bodies. So this is why and how Elul is the month that begins back to back and ends face to face. At the beginning of the month we are unaware of the reality that “I am to my beloved and my beloved is to me.” However, by working on ourselves during this month, by being willing to turn around and make changes, we come to realize that our Creator has never had His back turned. He has always been facing us, and just waiting for us to turn around. And once we do, we are then like two lameds that are face to face, which form the Jewish heart and which are the essence of the month of Elul. Elul then must be understood as an aleph, representing G‑d, followed by a lamed, vav, lamed—a lamed that is connected (vav) to the other lamed. And the Jewish heart, this idea of love as a totality of connection, is not merely the work for the month of Elul, but is the entire purpose of our creation. This Jewish heart is a symbol for why we were created and what we are meant to accomplish. For the Torah is the blueprint of creation, and the guidebook of how we connect to the divine. And it is not a book that has a beginning, middle and end, but rather a scroll, since we are taught that the “end is wedged in the beginning, and the beginning in the end.” So what do we find when the Torah scroll’s end rolls into the beginning? How does the Torah end and begin? The last word of the Torah is Yisrael, Israel, which ends with the letter lamed; and the first word is bereishit, meaning “in the beginning,” which begins with a beit. When we join the first and last letters of the Torah, we have lev, the Hebrew word for heart.” (The Jewish Heart, The Secret of Elul, Sara Esther Crispe)

13. Solomon’s temple had two brass freestanding columns:

a. “Jachin [and] Boaz The names of the two monumental pillars, set up to the right and left of the portico. Their exact nature is uncertain, due to uncertainties about the meaning of the terms and the various formulations found in the Bible and ancient translations. Nevertheless, it is certain that freestanding columns were part of ancient Temple architecture.” (Jewish Publication Society commentary, 1 Kings 7:21, 2002 AD)

b. “The most reasonable suggestion is to take these names as the catchwords of sentences that had been inscribed on the columns, one on each; the first: ykyn (= Jachin) ksʾ dwd wmmlktw lzrʿw ʿd ʿwlm, “He will establish the throne of David and his kingdom for his offspring forever”; and the second: bʿz (Boaz) yhwh yśmḥ mlk, “In the strength of YHWH shall the king rejoice” (originally proposed by Scott 1939).” (AYBC, 1 Ki 7:21)

c. “His first project was to build two huge free-standing pillars topped with intricately decorated, blossom-shaped capitals. The open capitals on top of the thirty-foot-high columns may have been filled with oil and then ignited to serve as huge lampstands in the courtyard in front of the temple proper. The one on the right was given the name “Jachin,” meaning “He shall establish,” and the one on the left the name “Boaz,” meaning “in strength. Why the columns were named is not revealed, but some interesting guesses have been proposed. … The simplest explanation is that the columns were named to symbolize the presence of the strong name of Yahweh in the temple, and the permanence of His covenant with Israel. Whatever the meaning of the names, the columns must have been an awesome sight to those who approached the vestibule of the temple.” (The Preacher’s Commentary Series, Volume 9: 1, 2 Kings, 1987 AD)

d. “2 Chron. 3:15 לִפְנֵי הַבַּיִת, and in v. 17 עַל־פְּנֵי הַהֵיכָל, “before the house,” “before the Holy Place.” This unquestionably implies that the two brazen pillars stood unconnected in front of the hall, on the right and left sides of it, and not within the hall as supporters of the roof.” (K&D, Commentary on the Old Testament, 1 Kings 7:21)

e. “It is not entirely clear what these pillars represent. Keil believes they symbolize the strength and stability of the kingdom of God in Israel. Gray suggests they “may symbolize the presence and permanence of Yahweh and the king.” Jones combines these two ideas, for he argues that the pillars “symbolized the covenant between God and his people, and especially between him and the Davidic dynasty.” Certainly worshipers would see the impressive monuments and reflect on all these ideas. God’s strength and Israel’s stability are both highlighted in the Davidic Covenant.” (New American Commentary, 1 Kings 7:15-22, 1995 AD)

f. “Much detail is given in 1 Kings 7:17–20, 22 to demonstrate the beauty and intricacy of these free-standing monuments. The pillars were erected on either side of the temple portico (the roofless front porch). Jakin, the name of the south pillar, means “He [Yahweh] establishes,” and Boaz, the name of the north pillar, means “In Him [Yahweh] is strength.” These stood as a testimony to God’s security and strength available to the nation as she obeyed Him.” (The Bible Knowledge Commentary, 1 Kings 7:17-20, 1985 AD)

g. “Jachin [and] Boaz The names of the two monumental pillars, set up to the right and left of the portico. Their exact nature is uncertain, due to uncertainties about the meaning of the terms and the various formulations found in the Bible and ancient translations. Nevertheless, it is certain that freestanding columns were part of ancient Temple architecture.” (Jewish Publication Society Bible commentary, 1 Kings 7:21, 2002 AD)

h. "He also made two pillars for the front of the house, thirty-five cubits high, and the capital on the top of each was five cubits. He made chains in the inner sanctuary and placed them on the tops of the pillars; and he made one hundred pomegranates and placed them on the chains. He erected the pillars in front of the temple, one on the right and the other on the left, and named the one on the right Jachin and the one on the left Boaz." (2 Chronicles 3:15–17)

i. “The pillars were brazen [made of brass], and begin the list of all the metal articles, which were first finished by the peculiarly skillful artisan Hiram, after the building of the temple was completed (chap. 6:14, 37, 38). If they had been designed to bear up the roof of the porch or the projection of its entrance, they could not have been vessels, but necessary integral parts of the building; but as this was “finished” without them, and as supporting pillars of brass are never found in stone and wooden buildings; these pillars, which were works of art, could not have had an architectural but only a monumental character, and this is shown by the names attached to them. Stieglitz truly says: “It was their separate position alone which gave these pillars the impressive aspect they were designed to wear, and the significant dignity with which they increased the grandeur of the whole, while they shed light upon its purpose.”” (A Commentary on the Holy Scriptures, J.P. Lange, 1 Kings 7:21, 2008 AD)

j. “The two pillars Jachin and Boaz were no more an innovation than the erection of a house instead of a tent; they owed their existence to the conditions that distinguished a new period of the theocracy. This we learn from their suggestive names. Jachin refers to the fact that Jehovah’s dwelling-place, hitherto movable and moving, was now firmly fixed in the midst of His people; Boaz tells of the power, strength, and durability of the house. Both were monuments of Jehovah’s covenant with His people, monuments of the saving might, grace, and faithfulness of the God of Israel, who at last crowned the deliverance from Egypt, by dwelling and reigning ever in a sure house in the midst of His people. It stands to reason that such pillars could not have been placed before the tent; they could only stand before the house, where they belonged to the porch, for it was the latter that gave to the dwelling-place the appearance of a house and a palace, in distinction from that of a tent. They were formed in accordance with their signification, being not of wood, not slender and slight, but of brass, thick and strong, which gave the impression of firmness and durability. The crown (capital), which is the principal characteristic of every pillar, consisted mainly, as did the brazen sea, of an open lily-cup. The Hebrew named the lily simply “the white,” (שׁוּשַׁן from שׁוּשׁ, to be white;) it is, therefore, a natural symbol of purity and of holiness to him.” (A Commentary on the Holy Scriptures, J.P. Lange, 1 Kings 7:21, p89, 2008 AD)

k. “The purpose of the two huge pillars (about 27 ft/8 m high) is not clear. They did not support anything but were freestanding, located in front of the temple portico. They were topped with elaborately decorated, lily-shaped capitals. Their names, Jakin and Boaz, are something of a puzzle, but the most likely theory is that these were the opening words of two inscriptions. On the basis of the various expressions found in the Psalms it has been suggested that the inscriptions may have read roughly as follows: ‘Yahweh will establish [jakin] thy throne for ever’, and ‘In the strength [boaz] of Yahweh shall the king rejoice.’ If this is correct, the pillars may have commemorated God’s promises concerning the Davidic dynasty. There are hints later in Kings that on taking the throne a king stood by one of these pillars to pledge himself to keep God’s covenant laws (2 Ki. 11:14; 23:3).” (The New Bible Commentary, D. A. Carson, 1 Kings 7:13-47, 1994 AD)

14. Physical History of Solomon’s Two freestanding brass columns:

a. 966 BC: Solomon puts the two freestanding brass columns out front of the Temple.

b. 587 BC: Nebuchadnezzar destroys: "Now the bronze pillars which belonged to the house of the Lord and the stands and the bronze sea, which were in the house of the Lord, the Chaldeans broke in pieces and carried all their bronze to Babylon." (Jeremiah 52:17)

c. 835 BC: Young king Joash was anointed king beside one of these pillars: "Then he brought the king’s son out and put the crown on him and gave him the testimony; and they made him king and anointed him, and they clapped their hands and said, “Long live the king!” When Athaliah heard the noise of the guard and of the people, she came to the people in the house of the Lord. She looked and behold, the king was standing by the pillar, according to the custom, with the captains and the trumpeters beside the king; and all the people of the land rejoiced and blew trumpets. Then Athaliah tore her clothes and cried, “Treason! Treason!”" (2 Kings 11:12–14)

d. 623 BC: Josiah re-established the covenant of Moses beside the pillar: "The king (Josiah) stood by the pillar and made a covenant before the Lord, to walk after the Lord, and to keep His commandments and His testimonies and His statutes with all his heart and all his soul, to carry out the words of this covenant that were written in this book. And all the people entered into the covenant." (2 Kings 23:3)

e. 515 BC: Ezra’s temple completed without any record of pillars or columns.

15. CHURCH ANTITYPE: Discussion and analysis of meaning and symbolism behind Solomon’s temple freestanding columns:

a. King David designed them with the help of Hiram king of Tyre.

b. They were freestanding and therefore symbolic of something important. They were not needed for any structural reasons and were purely “decorative”.

c. The columns are the only architectural element of the Temple that received names.

d. The names Boaz and Jachin were engraved into the columns: Although scripture is silent on the matter, the two names were obviously carved in the columns as an engraving.

e. The two names Jachin and Boaz. The names literally translate to: North pillar “Jachin = establishes”; South pillar “Boaz = strength”. The idea is thought to mean either YHWH is the one who establishes and strengths: His covenant and/or the David kingdom.

f. The columns were brass: Twice in Revelation, Jesus’ feet are equated with polished bronze. Feet are the foundation and stability and support of the entire body: "His feet were like burnished bronze, when it has been made to glow in a furnace, and His voice was like the sound of many waters." (Revelation 1:15) "“And to the angel of the church in Thyatira write: The Son of God, who has eyes like a flame of fire, and His feet are like burnished bronze, says this:" (Revelation 2:18)

g. In ancient Synagogues, pillars were used to execute justice when criminals were tied to pillars and beaten according to Mosaic law: There is a sense in which Christians will judge the world: "Does any one of you, when he has a case against his neighbor, dare to go to law before the unrighteous and not before the saints? Or do you not know that the saints will judge the world? If the world is judged by you, are you not competent to constitute the smallest law courts? Do you not know that we will judge angels? How much more matters of this life? So if you have law courts dealing with matters of this life, do you appoint them as judges who are of no account in the church?" (1 Corinthians 6:1–4)

16. The symbolism of pillars is used in the New Testament as an antitype for the church and the individual Christian:

a. Solomon’s two columns had names inscribed on them.

b. “Columns to support the roof are an essential element in most public buildings and were found in almost all excavations of ancient synagogues. Donors to the synagogue often inscribed their names and the names of others on these columns as dedicatory inscriptions, as they were readily visible to all, thus affording maximum exposure and recognition. Such columns were found, inter alia, at Dabbura in the Golan and at Gush Halav, Capernaum, and Khirbet Yitztiaqia (south of Bet Shearim). One “Shim'ai, son of Ocsantis”, from Bet Guvrin purchased a column "in honor of the congregation”” (The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, Lee Levine, p340, 1987 AD)

c. The church is composed of individual “freestanding column Christians” who uphold the truth to death: "household of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and support of the truth." (1 Timothy 3:15)

d. Just as Solomon’s two brass columns were ENGRAVED with special names, so too God will ENGRAVE three things on us: God’s Name, the name of the New Heavenly Jerusalem and the New name of Jesus: "‘He who overcomes, I will make him a pillar in the temple of My God, and he will not go out from it anymore; and I will write on him the name of My God, and the name of the city of My God, the new Jerusalem, which comes down out of heaven from My God, and My new name." (Revelation 3:12)

By Steve Rudd 2017: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections

|

Jesus your messiah is waiting for you to come home! |

|

|

Why not worship with a first century New Testament church near you, that has the same look and feel as the Jewish Synagogue in your own home town. As a Jew, you will find the transition as easy today as it was for the tens of thousands of your forefathers living in Jerusalem 2000 years ago when they believed in Jesus the Nazarene (the branch) as their messiah. It’s time to come home! |

|

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Go to: Main Ancient Synagogue Start Page