Beidha, Jordan (Biblical Kadesh Barnea, Sela, Joktheel, En-mishpat)

Location: 30.370780°N 35.447756°E

Preamble:

We know from scripture and ancient literary sources that Kadesh Barnea was located in the Petra area. While Late bronze pottery has been found at Petra, other sites like Beidha and Basta have attracted the attention of Steven Rudd. The Hebrew Exodus population of 3.5 million would clearly take up a space up to 15 km long. Beidha is 5 km north of Petra and Basta is 12 km SE of Petrra. The problem of course, is that both Beidha and Basta are both PPN (pre-pottery Neolithic) sites, meaning there is no pottery found at either site. PPN sites sites are dated to 6500 BC strictly because of the lack of pottery, yet this is clearly mistaken because PPN is contemporaneous all the way down to the Iron age. There have always been isolated sites that never used pottery and it is a mistake to automatically date them thousands of years before the Early Bronze Age for that reason alone. While it is clear that evolutionary dating of the PPN sites of Beidha and Basta at 6500 BC is absurd given the creation of the world was at 5554 BC, the lack of Late Bronze Age pottery at Beidha and Basta poses a problem because it was during the Late Bronze Age that the Hebrews spent 38 years in the Petra area. Solutions to this problem might be found in the fact that Israel drank miraculously supplied water and manna all the time they were at Kadesh and God miraculously kept their clothing and shoes from wearing out. Could this miracle have extended to their pottery as well. Perhaps God miraculously preserved their pottery from breaking while at Kadesh, or perhaps, maybe they did use ceramic pottery to cook/boil the manna. A problem is that if the early round-roomed city from the time of Abraham predated the Hebrews rectangular-roomed city, we would expect to find pottery in the round-roomed city, but do not. Both round and rectangular cities had no pottery. In other words, all the miraculous reasons why we might not find pottery at the site during the time of Moses would not be expected to exist in the earlier round-roomed city that dates back to the time of Abraham in the Early Bronze Age.

1. "The sons of Israel ate the manna forty years, until they came to an inhabited land; they ate the manna until they came to the border of the land of Canaan." (Exodus 16:35)

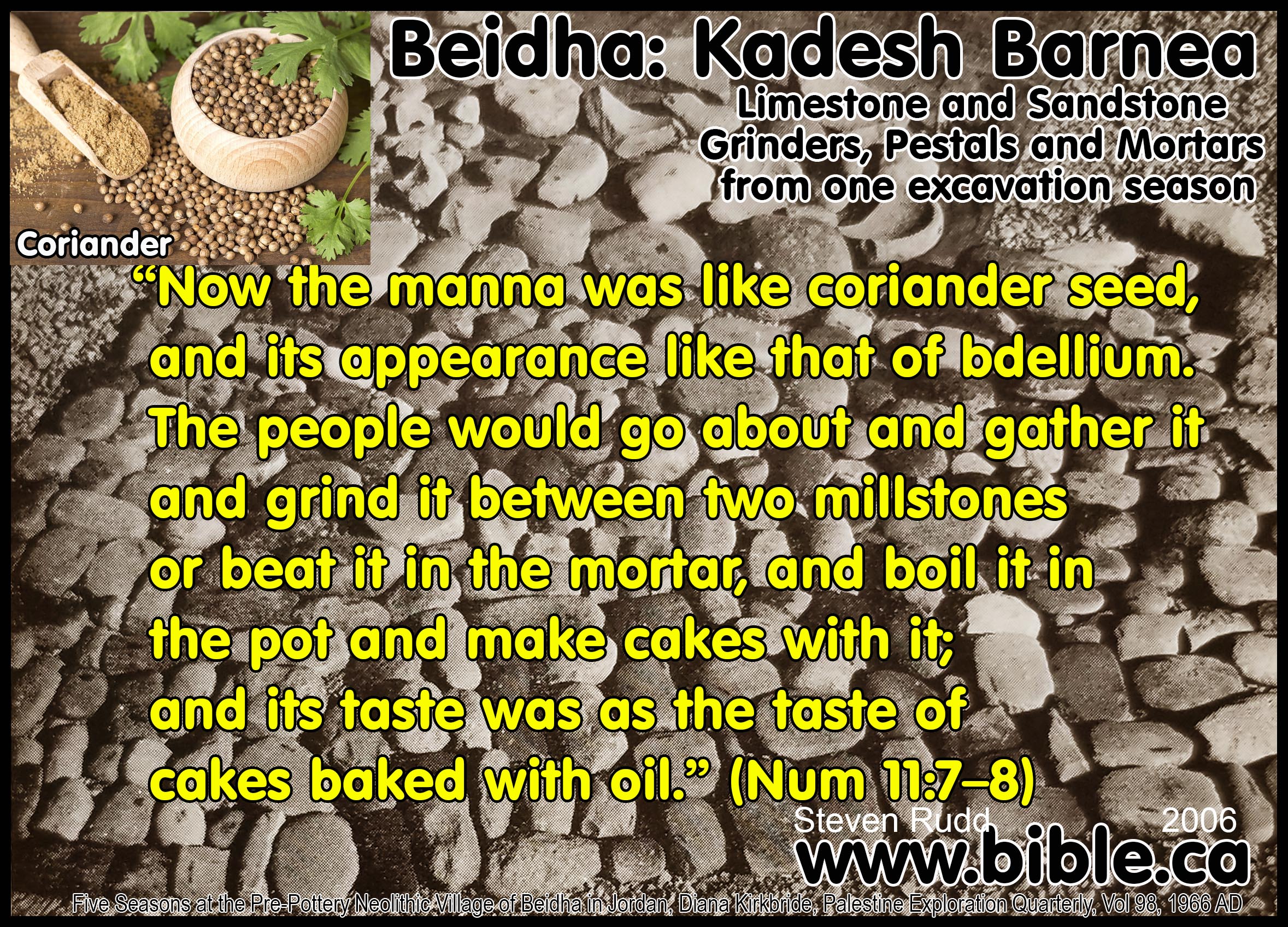

2. "Now the manna was like coriander seed, and its appearance like that of bdellium. The people would go about and gather it and grind it between two millstones or beat it in the mortar, and boil it in the pot and make cakes with it; and its taste was as the taste of cakes baked with oil." (Numbers 11:7–8)

3. "Your clothing did not wear out on you, nor did your foot swell these forty years. " Deuteronomy 8:4

4. "I have led you forty years in the wilderness; your clothes have not worn out on you, and your sandal has not worn out on your foot. " Deuteronomy 29:5

5. "Indeed, forty years You provided for them in the wilderness and they were not in want; Their clothes did not wear out, nor did their feet swell. " Nehemiah 9:21

Introduction:

See also Kadesh Barnea.

See also Petra.

See also Basta: Massive dump of 100,000 bones, possibly from the 38 years at Kadesh Barnea.

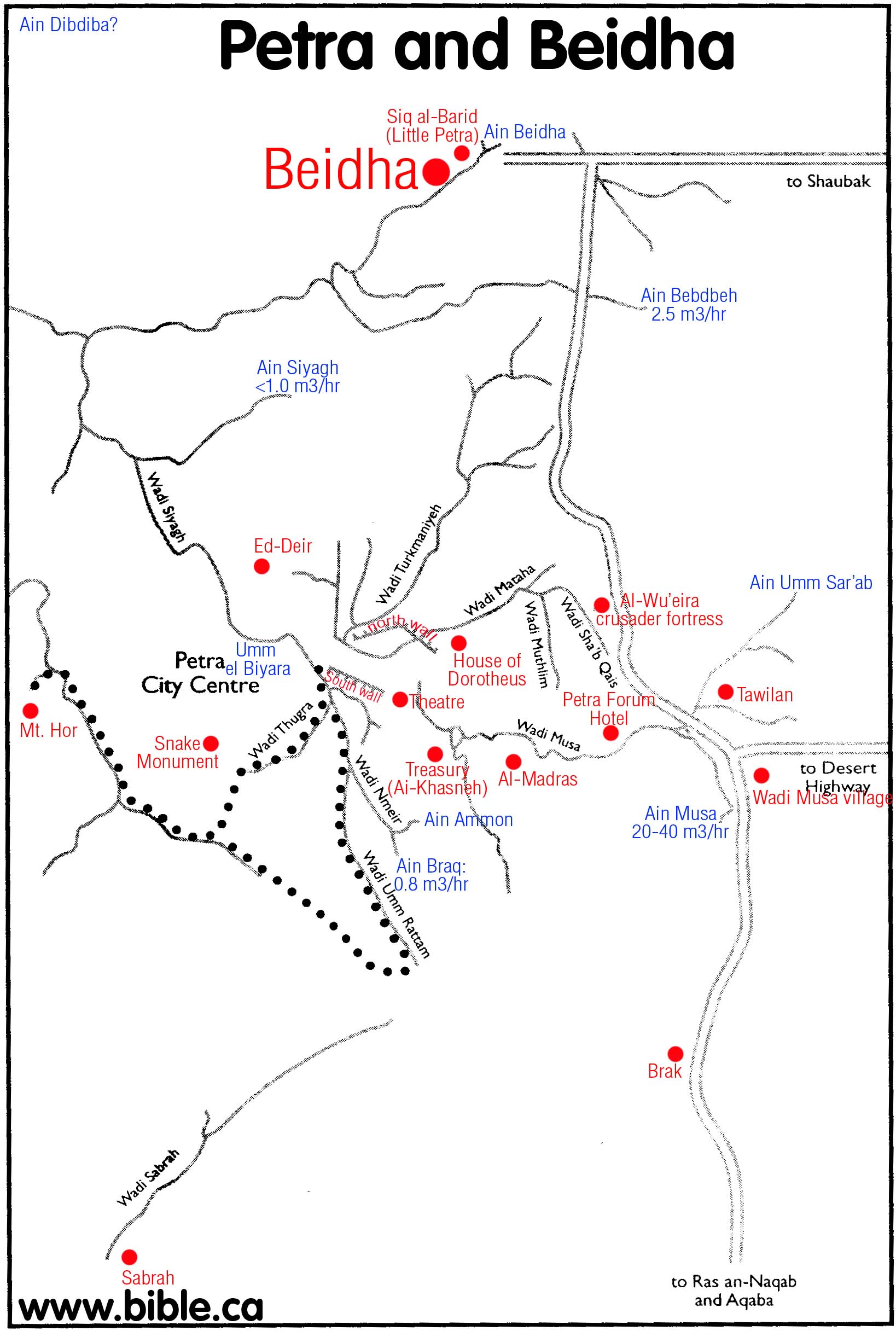

1. Beidha, Jordan is the location of Biblical Kadesh Barnea, Sela, Joktheel, En-mishpat, which is 5 km north of Petra.

2. The Exodus took place in 1446 BC but since they arrived in Kadesh Barnea in 1444 BC exactly two years after leaving Egypt. "Then the sons of Israel, the whole congregation, came to the wilderness of Zin in the first month; and the people stayed at Kadesh." Numbers 20:1

3. After a careful research of the Bible and history, it became evident that Kadesh was either at or just 5 km north of Petra is Beidha which has traces of human occupation going back as far as the flood in 3298 BC.

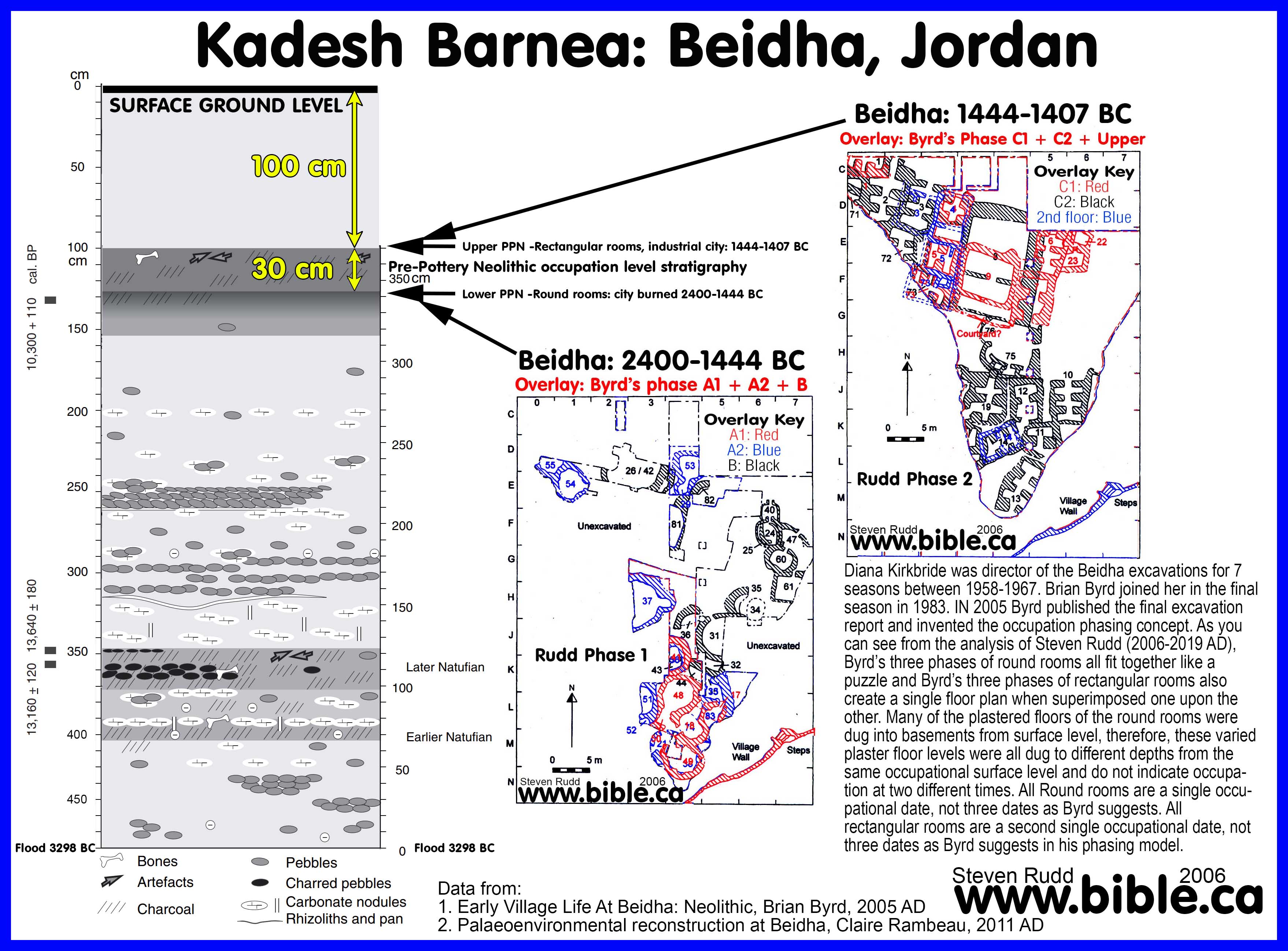

4. Both Diana Kirkbridge (the director of excavations) and Brian Byrd (volunteer the last season) suggest that Beidha has a Natufian period of occupation around 9000 BC, followed by a period of abandonment. Then between 7000 - 5000 BC a Neolithic period of occupation [round and rectangular cities] occurred with three phases followed by abandonment until the site was developed by the Nabataeans about the time of Christ (300 BC - 100 AD) We have accepted the facts of what Byrd had presented, however we have our own interpretation of the archeology at Beidha. Since Byrd rejects the Noahic flood story of the Bible, he sees no problem with these dates. As Bible believing Christians, we are forced to either reject the Bible as God's word or reject Byrd's interpretation of dates.

a. "The Natufian [9000 BC] at Beidha is best characterized as a short-term or seasonal camp site that was occupied repeatedly over a considerable period of time. The limited evidence of spatial variability between provenience units in the chipped stone artifact samples, the range of activities implied by the chipped stone assemblage (primarily hunting related activities), the presence of small hearths and large roasting areas, and the absence of elements typically associated with more permanent occupations — large ground stone implements, and features such as houses, storage facilities and burials — support this interpretation." (The Natufian Encampment at Beidha, Late Pleistocene Adaptation in the Southern Levant, Brian F. Byrd, 1989 AD, p85)

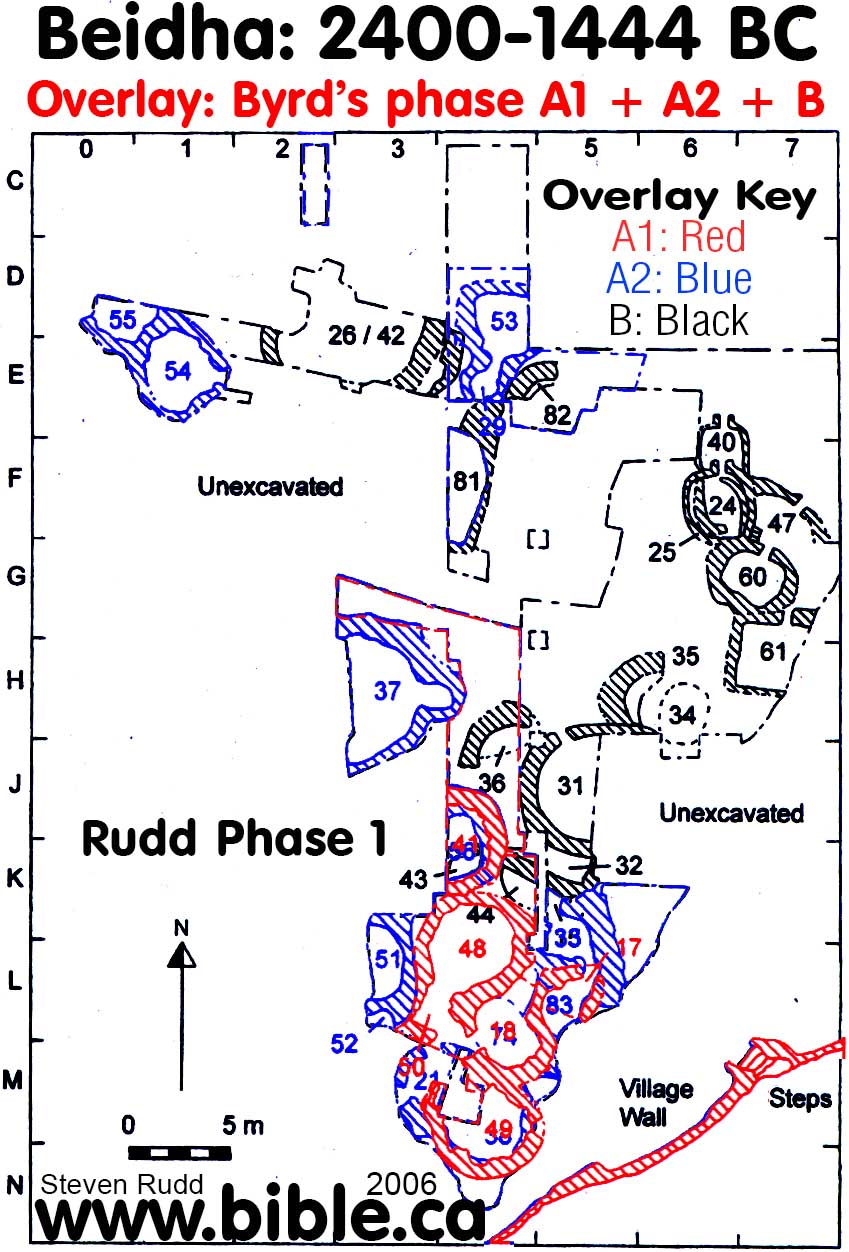

5. Our interpretation has two clear departures from Byrd's view: First: We take Byrd's time scale for all three phases and squeeze them into a period between about 3298 BC - 1406 BC. Second: Whereas Byrd sees three phases (A, B, C), we only see two phases (1, 2). Please take note that in this document, when you see "Phase 1" or Phase 2", that this is our interpretation. We understand ahead of time, that our interpretation is different from Byrd's, but as you will soon see, there are some very good reasons for our interpretation. Our interpretation must at least be considered as plausible, even if rejected by mainstream archeologists. It is important to note, that we do not question what Diana Kirbridge and Byrd dug up and found, we question their interpretation of the findings.

6. Byrd describes two features were used in all three occupation levels: The village wall and the stone lined pit in Phase C building 81: "The latest phase B structure documented in the north-central area was large building 81. Only the base of the walls along the eastern edge of the building and an associated stone-lined pit directly to the northeast were exposed. The building lay directly under the floor and walls of phase C large building 9 (Figs 26-27), and the stone-lined pit continued to be used in phase C. This patterning is evidence of continuity in occupation from phase B to phase C." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

7. Beidha is unique for a hundreds of mile radius (the Levant) in that is actually documents a long continuous history of use. This was an important site: "This overview of the phasing history affirms the presence of a continuous architectural sequence ranging from clusters of round post houses, both semisubterranean and semidetached, through individual subrectangular examples, and then ultimately true rectangular buildings (primarily corridor buildings). The Beidha architectural sequence is, at present, unique in the Levant, but shares much in common with slightly earlier developments in other portions of Southwest Asia" (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

8. Carbon dating is notoriously inaccurate:

a. One of the best kept secrets in the science world, is that dating labs will not accept samples unless you tell them in advance when you think the sample is dated, where it came from and the implications of that date in relation to Evolution theory. If you submit a dinosaur bone for radiometric dating that generates a hard, uncalibrated date of under 25,000 years, they will adjust the date to say millions. There are also a long list of variables that determine the uncalibrated date.

b. The author has first hand experience where a lab generated a date of about 2000 years old of a dinosaur figurine from Acámbaro Mexico until they learned what the sample was and the significance of the date, so they redated it to 75 years old, therefore making the dinosaur figurines modern frauds as opposed to ancient ceramic art.

c. “Carbon dating samples taken mainly from phase A because very few of the other phase buildings burned: "The prevalence of samples from phase A was not surprising, since very few buildings from the other phases burned." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

d. In those rare instances were double-blind, carbon dating tests are conducted, the dates vary greatly with testing done in labs who ask in advance the date you expect to generate for the samples submitted.

A. Connecting Beidha with Kadesh Barnea:

1.

TWO “NEOLITHIC” PHASES NOT THREE: The earlier round-roomed city

buildings existed at the time of Abraham, and were houses that were burned,

possible by Moses or by someone else before the Hebrews arrived.

2. MASTER BLUEPRINT: The rectangular workshop city appears to be designed in advance and built at the same time as a calculated architectural plan. This is what you would expect from a large population arriving as opposed to a small settlement that grows over time. The only renovation was the original large central room was enlarged over top of a row of previously built smaller rooms to the east.

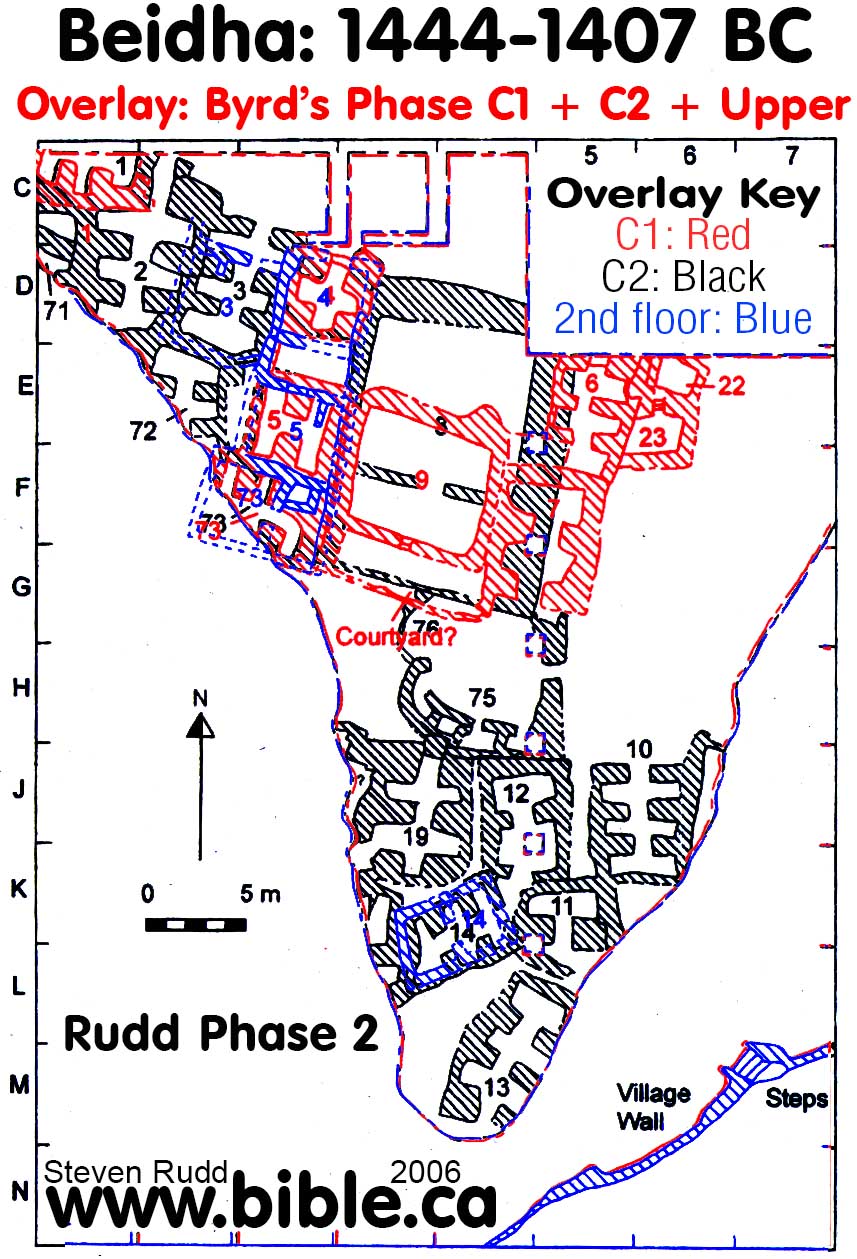

a. "A new style of architecture began in phase C and was used throughout the settlement. This novel corridor building architecture appeared fully developed without antecedents at the start of phase C. It was a distinctive technological and organizational development comprised of two internally subdivided stories - one as a basement and the other set slightly above ground level. Each story had a separate entrance. The upper stories were open in plan and had plastered floors. In contrast, the basements were comprised of multiple small rooms, with a variety of features (except hearths) within them, and had earthen floors. Several single-story quadrilateral buildings (both large and small), coexisted with these corridor buildings and provide evidence of continuity with earlier architectural traditions." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

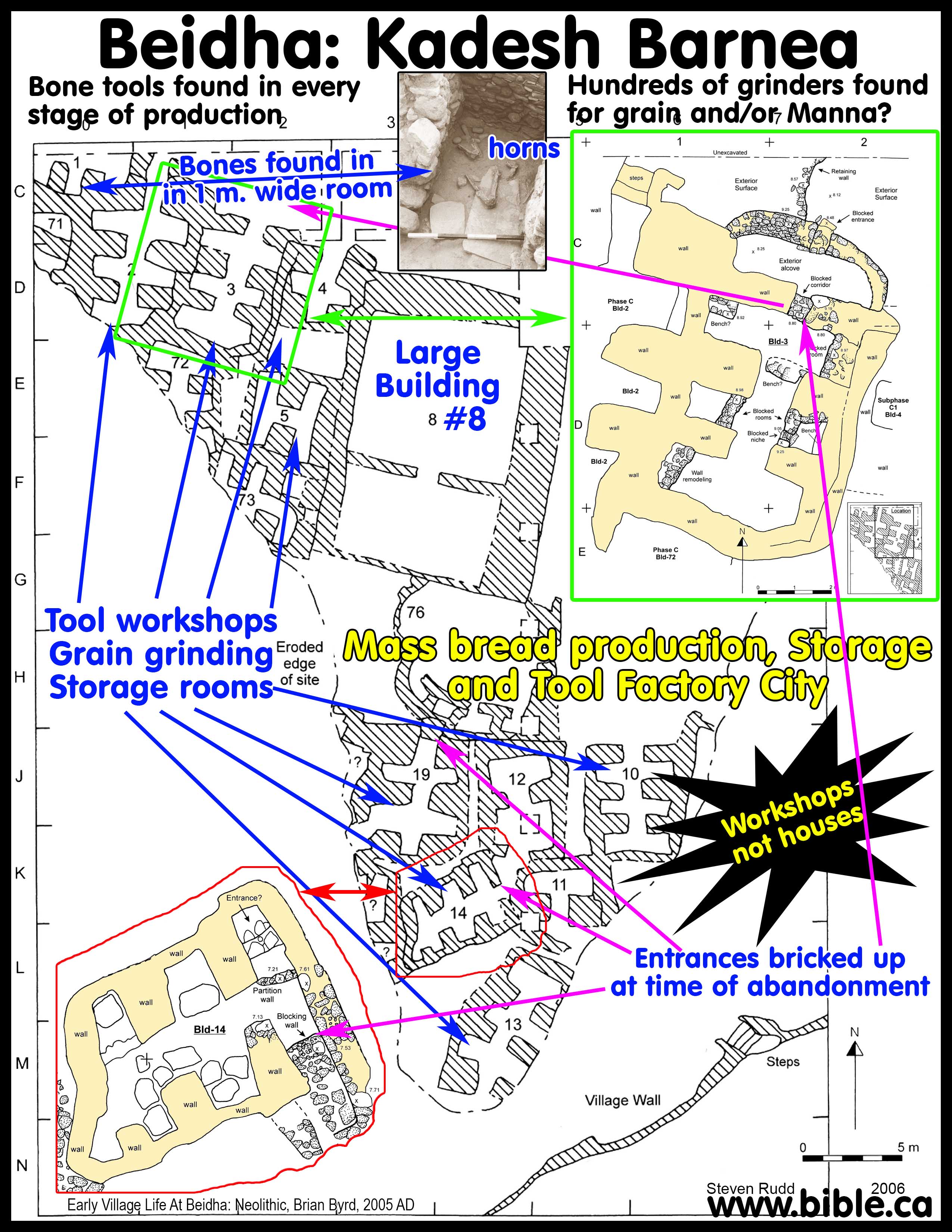

3. WORKSHOPS NOT HOUSES: The latter rectangular-roomed city buildings were workshops, not houses that were abandoned in ancient times until the time of the Nabateans (100 BC). Many tools and jewelry were excavated in the small rooms in every stage of production. These rooms were tool factories not residential dwellings to sleep in.

4. MASS PREPLANNED ABANDONMENT: Most peculiar was the excavations discovered the entrance doors of the smaller work rooms were purposely sealed up with stone, perhaps indicating a calculated and planned mass-exodus from the cite at one time, with the expectation of a possible later return. While the lower/older round-roomed city was entirely burnt, nothing was burned in the upper/newer rectangular-roomed city at the time of the final abandonment.

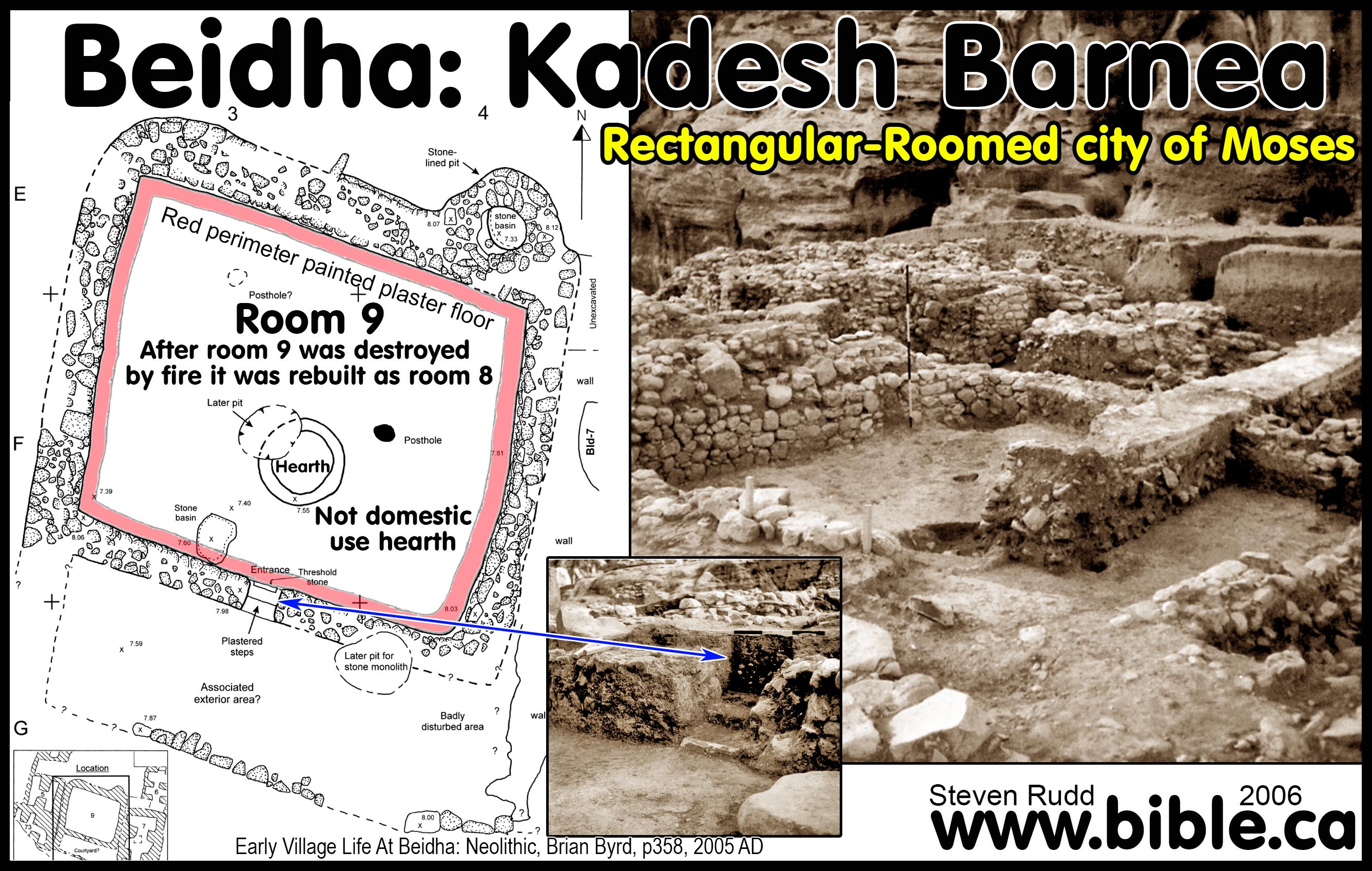

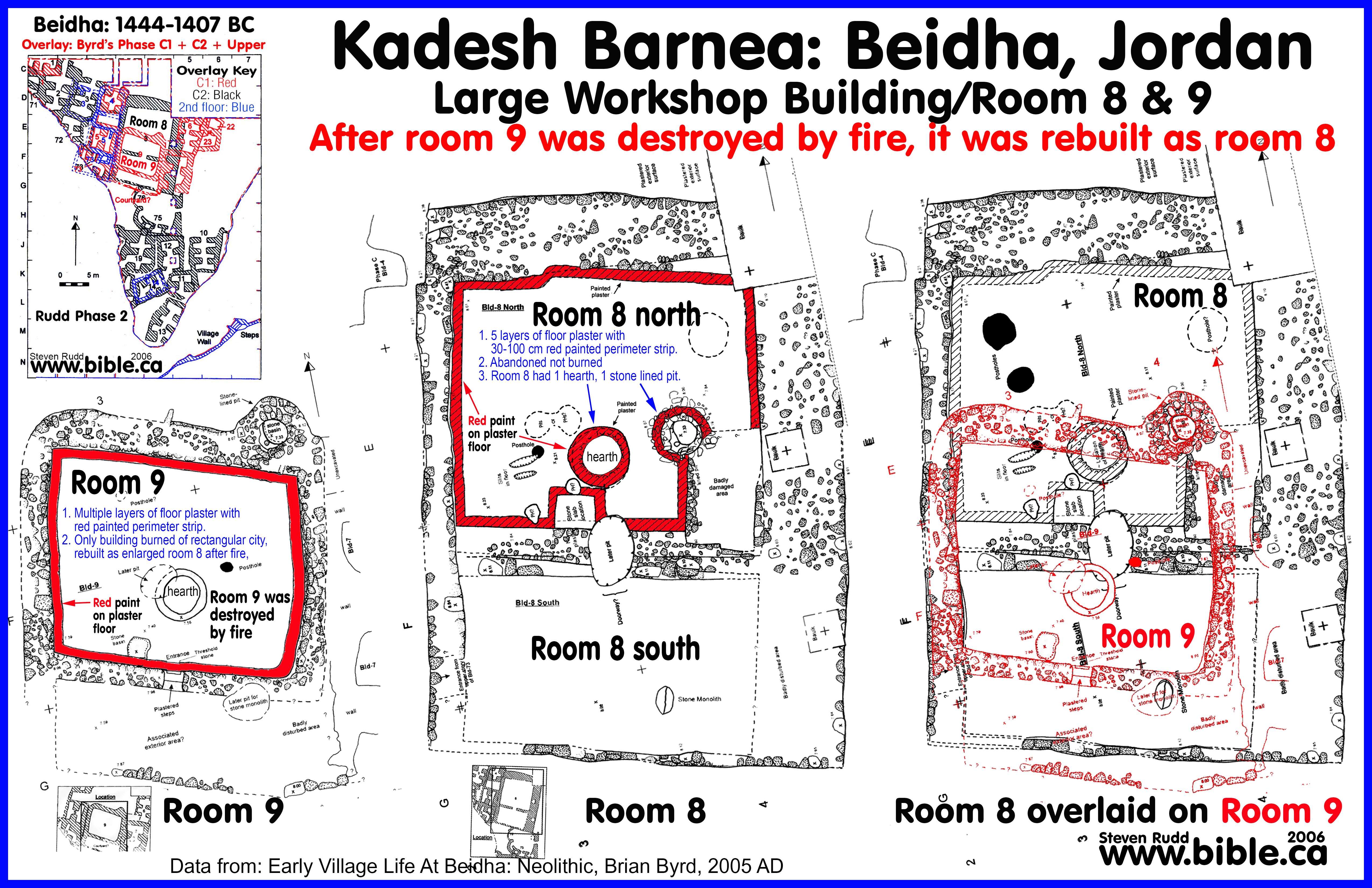

5.

LARGE CENTRAL ROOM: In the centre of the rectangular-roomed city was

a large building that Byrd named Building 8 and 9. Building/Room 8 was built

over building/Room 9. Room 9 was renovated and enlarged into room 8. Booth

Rooms 8 and 9 were plastered multiple times and both had the same red perimeter

strip (~30 cm) on the plastered floor. Room 9 had a red 30 cm wide red band

painted on the floor that outline several installations in the floor. Building

9 was the only one room burnt in the entire rectangular city. This was likely

part of the demolition and renovation process to make way for the larger room 8

built directly on top of it. The burning may have been a way of disposing of

the roof to make way and prepare for the new structure. This larger room had a

raised elevation of 50 cm and the eastern wall was triple thick stone build

directly over top of rectangular buildings 6 and 7 which were not burnt. The

floor of room 8 was plastered 5 times and the top layer of floor plaster

featured a double red stripe around the perimeter walls that wrapped around the

working stations. There was no oven, hearth or fire pit in the large room 8.

6. NO FIRES FOR FOOD PREPARATION: Workshops contained no tabuns, ovens or fire pits meaning that no cooking was done in the entire work-city with the rectangular rooms. This may explain why no pottery was found in the upper city. The city changed from round domestic houses with tabuns, fire pits and ovens for food preparation, to rectangular workshops with no tabuns, firepits or ovens.

7. HUNDREDS OF GRINDERS (for Manna?): Large numbers of grinders were excavated at Beidha by Diana Kirkbride in the first three seasons 1960,1963-4. Below is a photo of grinders excavated from a single season the total was much more from all 7 seasons. While it was a factory for tool manufacturing, it was also a mass food preparation city. Remember, there were no fires of any kind excavated in the rectangular city. This proves that grains that were ground in the limestone querns etc, were not for consumption on site. It is clear, that these hundreds of grinders were used for mass food production for consumption outside the city by a large nearby population. This is a perfect fit for the Hebrews at Kadesh Barnea who had to grind their Manna daily! This all indicates the rectangular-roomed city was massive industrial food manufacturing center for a large population. While nothing was cooked in the city, hundreds of grinders for grains and possible manna were found in the rectangular-roomed city indicating a large population was being fed.

a. GROUND STONE IMPLEMENTS: Grinders (Pl. XIX A; Fig. g, Nos. 1-3). These implements are the most numerous class. Plate XIXA gives a general view of a single season's collection [see photo below]. Not all of them were used for cereals, a minority bear traces of ochre grinding. In shape, although the majority are elongated ovals, there are sub-rectangular, bun-shaped and oval examples. The tops are either flat, sometimes re-used, rounded or keeled, the latter chiefly in granite specimens, and one prototype of a flat iron with a solid handle. They are made from limestone, sandstone, granite and a coarse-grained basalt.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p35, 1966 AD)

b. Pestles (Fig. 7, Nos. i-6, i o) are made chiefly of a fine-grained basalt though there is a minority of granite, which because of their weight might be classed as pounders, and sandstone and limestone examples. They vary in height from elegant specimens of c. 19 cm. to small, squat ones of 6 cm. One class of Mesolithic aspect has the top brought to a rounded knob; this slight `waisting' near the top is also present in most of the small, squat pestles (Fig. 7, Nos. 1-3). (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p35, 1966 AD)

c.

“Querns. A great number of querns, both

open-ended and closed and the fragments of such are scattered throughout the

site, in situ, built into walls, made into steps, or occurring in the fill and

in the rubbish dumps. They are chiefly limestone boulders and give

evidence of hard and prolonged use. Sometimes if the boulder was thick enough

and the original depression too deep it was turned over and re-used on the

other side; frequently if thin the bottom was ground out or almost so before it

was abandoned. Stone Bowls and Mortars. Whole specimens of bowls, usually made

of limestone, are rare; only three are recorded at present although some

fragments of rims and sections have been found. In spite of stone being

abundant, the inhabitants of Beidha probably preferred wooden bowls. Two small,

deep sandstone bowls or mortars with their own little pestles were found, but

here again the rarity of such objects or fragments points to the general use of

wood rather than stone for these vessels.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery

Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration

Quarterly, Vol 98, p32, 1966 AD)

B. About the excavations:

1. Excavations and publications:

a. Diana Kirkbride was director of the Beidha excavations for 7 seasons between 1958-1967. Brian Byrd joined her in the final season in 1983.

b. Diana Kirkbride’s 5-year report (1966) and Brian Byrd’s 2005 book on the excavations at Beidha both lack object lists and object levels.

c. In his 1989 book on the “Natufian Encampment” Byrd has a lot of nice drawings of flint and debitage that are disconnected from the excavation because of a lack of 3-dimensional recording. Individual objects are lumped into three general categories of high, medium and low elevations within broad archeological vertical columns. Although a Nabatean platform was noted on the surface, no record of any pottery of any kind was found on the surface. Byrd can hardly be faulted for this, given Kirkbride was the director and she excavated at the dawn of modern 3-dimensional archeology pioneered by Kathleen Kenyon. In 2005 Byrd published the final excavation report and invented the occupation phasing concept. Byrd does an excellent job of documenting, drawing and labelling individual rooms, some of which record wall and floor levels.

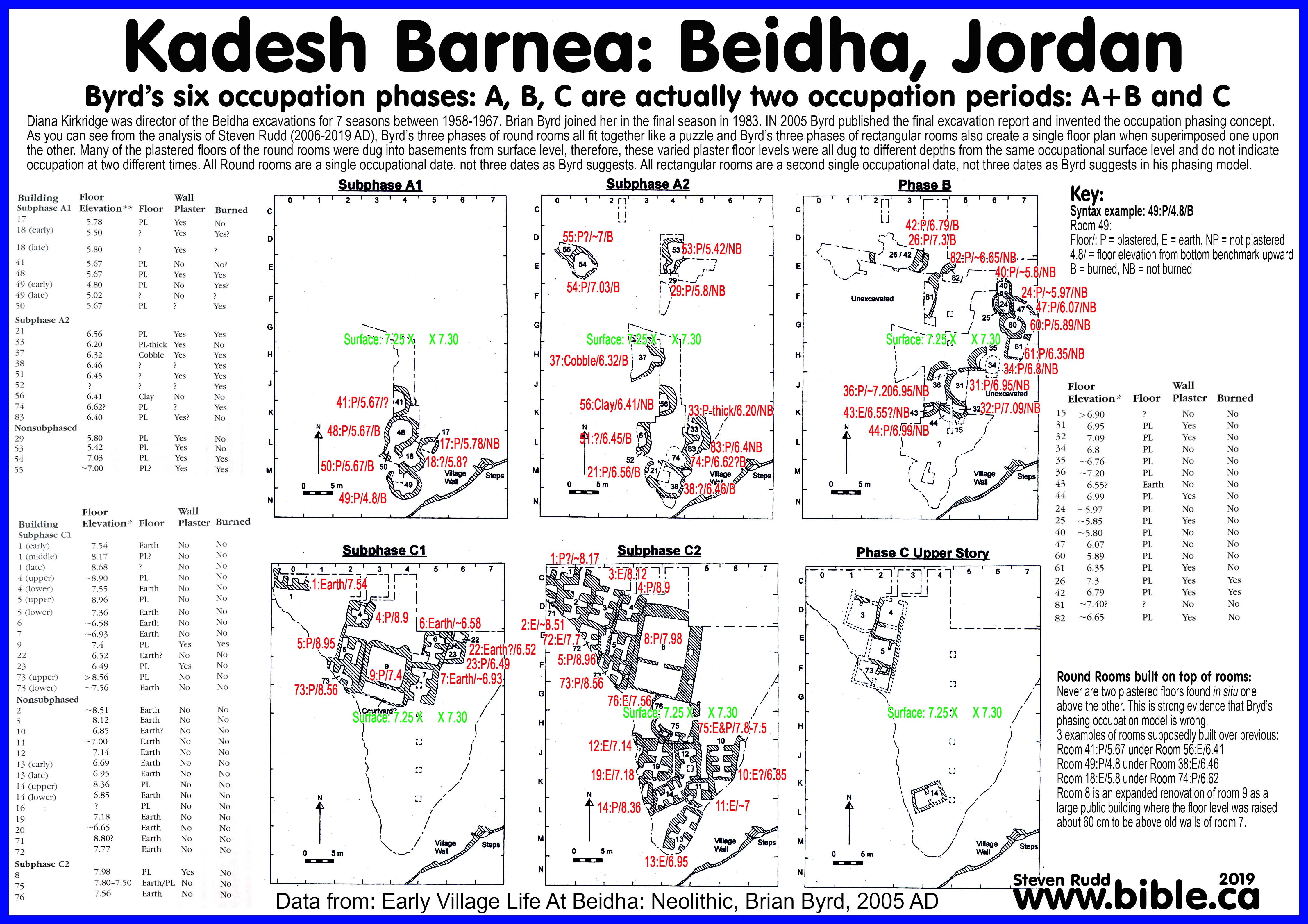

d. As you can see from the analysis of Steven Rudd (2006-2019 AD), Byrd’s three phases of round rooms all fit together like a puzzle and Byrd’s three phases of rectangular rooms also create a single floor plan when superimposed one upon the other. Many of the plastered floors of the round rooms were dug into basements from surface level, therefore, these varied plaster floor levels were all dug to different depths from the same occupational surface level and do not indicate occupation at two different times. All Round rooms are a single occupational date, not three dates as Byrd suggests. All rectangular rooms are a second single occupational date, not three dates as Byrd suggests in his phasing model.

2. Elevations are relative, not in sea levels:

a. Instead elevations are relative to an arbitrary benchmark deep inside the tell. Surface elevations are either unknown or impossible to calculate with accuracy. Diana Kirkbride doesn’t identify the benchmark and took few if any, surface elevations before excavations in each square. This makes it almost impossible to know how far the floor levels were below the original unexcavated surface level.

b. None of the balks have top elevations indicating original surface level before excavation. Only on page 299 of Byrd’s excavation report are two balk top levels given of 7.25m and 7.30m.

c. While the horizonal scales are excellent on the numerous square top plans, vertical scales are not indicated. To further confuse the matter, several of the drawings use different vertical and horizontal scales, without formally indicating the distortion.

3. Diana Kirkbride and Brian Byrd comment on the older curvilinear city:

a. “Some time about 7000 BC the newcomers, using a Neolithic flint assemblage, and already thoroughly conversant with domestic architecture to an extent that might even be termed town-planning, came to the site and apparently found the environment satisfactory for their main need, namely, to practise agriculture: the fundamental discovery that had freed man from his everlasting peregrinations in search of food during the hunting and gathering stage and enabled him to stay in one place.” (Beidha, Early Neolithic Village Life South of the Dead Sea, Diana Kirkbride, Antiquity, XLII, p265, 1968 AD)

b. “Phase A outdoor occupation levels then accumulated in this area, and individual deposits included clay floors, thin, possibly plastered floors, and associated features and facilities such as clay wall remnants, postholes, and hearths with fire-cracked rocks” (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, p17, 2005 AD)

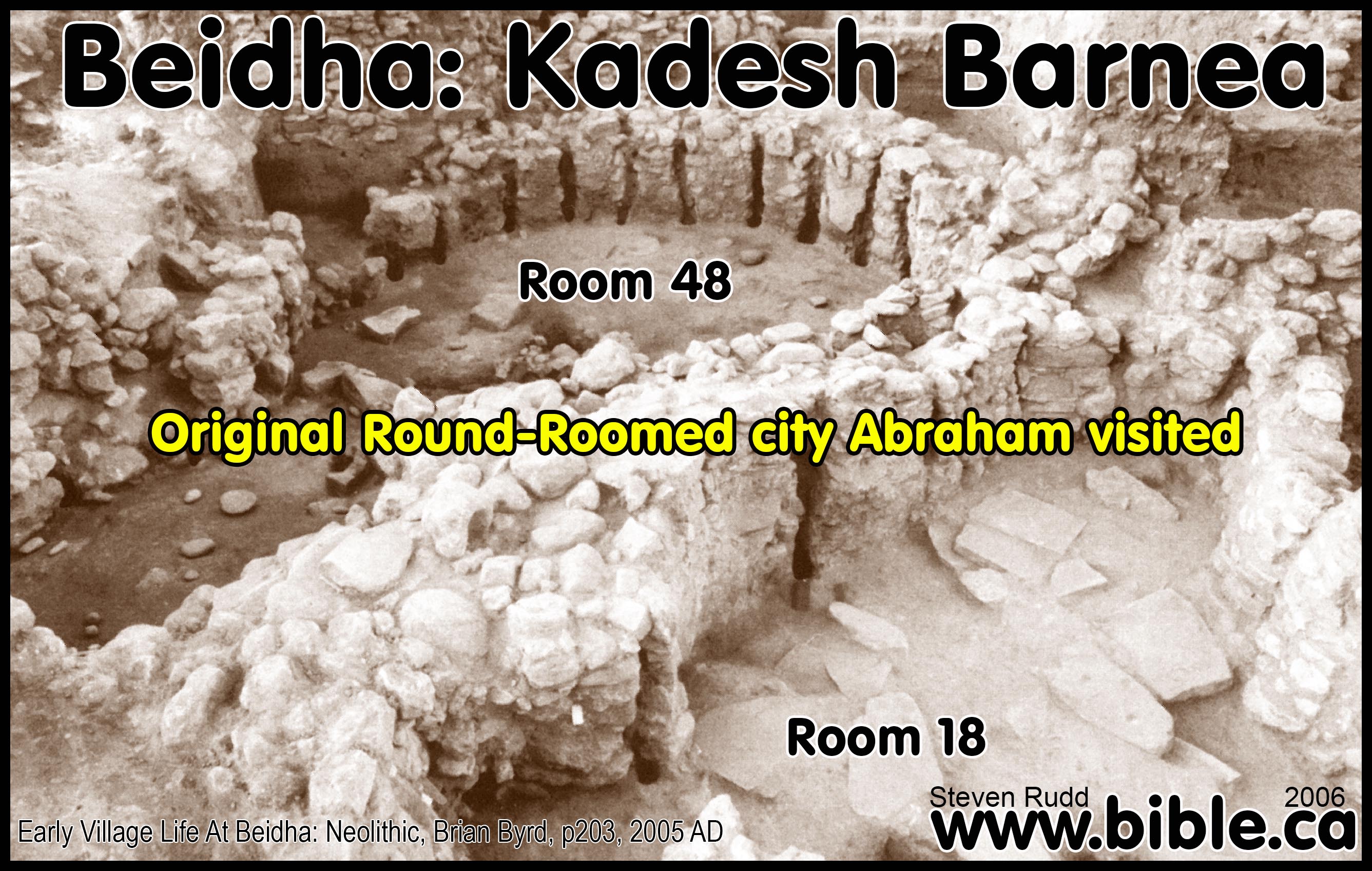

c. “The majority of the Level VI post-houses were destroyed by fire which, in view of all the wood they contained, is hardly surprising. Even though hearths were confined to the courtyards the precaution did not prevent severe conflagrations. Owing to this circum- stance we have a much fuller knowledge of this, the earliest period, than of all the subsequent ones, by reason of the preservation in their carbonized form of materials that would otherwise have perished; thus our evaluation is not confined entirely to flint and other stone implements, bone and shell. A brief description of the contexts of three adjacent burnt houses within a cluster will best illustrate the economy of the village and its vanished inhabitants.” (Beidha, Early Neolithic Village Life South of the Dead Sea, Diana Kirkbride, Antiquity, XLII, p267, 1968 AD)

d. “The earlier levels [curvilinear/round buildings] have not, as yet, shown any evidence for specialization. One small house in Level IV was obviously set aside for the preparation of cereals (Plate IX B). It contained three querns, two of them open-ended, several grinders and a small heap of hammer-stones; but apart from that the floors of the earlier levels have been disappointingly clean.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p25, 1966 AD)

e. “Level IV. Apart from the large burnt house which we have ascribed to this level, most of our evidence comes from buildings located on the eastern perimeter of the tell. These are unfailingly of different plan from the corridor complexes. of Levels II and III, although the large house of those levels can be described as enlarged and more angular versions of a typical Level IV house. These early houses are subrectangular in shape with gently curving walls; they are single-roomed and semi-subterranean each entered by three descending stone steps. In the majority of cases floors and walls were plastered, and two houses contain small versions of the hearths of the large houses with raised sills and the whole plastered (Pl. VII B). These buildings are separated from each other by open spaces or yards. Not only does the plan of the houses differ from those of Levels II and III but a different method of construction was favored. Instead of using roughly square boulders with, small stones racked m the interstices, they preferred straight, flat slabs of mud-stone which can be found in certain layers of the local, Cambrian sandstone. These slabs, carefully laid with a sandy mortar in between, make some of these walls objects of real beauty (Plate VIII A).” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p18, 1966 AD)

4. Diana Kirkbride and Brian Byrd comment on the younger rectangular city:

a.

“The large house contained several fittings within its single 9 x 7-m.

room. Walls and floor were covered with highly burnished whitish plaster like

that introduced in Level IV, with an area painted red and about a metre wide

running parallel to the base of the walls and continuing up them. A similar red

band outlined the hearth with its raised and plastered sill situated towards

one side facing the stepped entrance. Other important features were also

outlined in red; a large roughly square and highly polished stone seat or table

situated against the wall just inside the door, and a circular stone-lined pit

at the base of which was a large stone. The presence of similar large stones in

the same relative position in the earlier editions of this house show the pit

and stone had some important function, religious or not, which cannot be determined.

To this house were attached courtyards and beyond lay the rectangular houses,

all of identical size and construction, laid out in rows. These secondary

houses were long rectangles with entrances in the centre of one short side from

where three stone steps led down to the semi-basement floors. No trace of

curving walls or rounded comers is seen in these strictly angular buildings

each of which comprised a central corridor and six small cubicles (1 x 1.50 m.)

arranged three on each side. Strongly built stone baulks, some wider than the

rooms, separated the cubicles. From the objects found in these buildings it

seems they were workshops rather than dwellings and so it is probable that the

heavy baulks were interior buttresses upholding some lightly built upper

storey. In this case the cubicles would have been semi-basement stores and

working areas. Additional evidence for this may be deduced from the lack of

wall-plaster in these buildings; only the floors were plastered and this not in

every case. Arranged in straightish rows, these buildings shared party walls with

their neighbours. Perhaps the big house was the communal meeting place for the

adjacent workers for it contained the only interior hearth found in the level. The

corridor buildings naturally provided the bulk of the finds and these amply bear

out their workshop character. Here again is strong evidence for specialization of

the crafts as within the separate buildings. Among these we can distinguish workers

in horn, others concentrated on bone tools and beads; in many cases there was a

mixture, while a single specialist seems to have been a butcher. From an untidy

clutter of the raw material for the former, animal long bones and ribs, lying

in depth in the corridor and in his workroom. The tables on which he worked

were flat sandstone slabs lying on the floor, together with his tools and with

beads of stone, bone and shell in every stage of the making. Some stone beads

were found with the grinding process unfinished, others with the perforation

just begun, while most were finished, ground, polished and pierced. Bone beads

also occurred in plenty.” (Beidha, Early Neolithic Village Life South of the

Dead Sea, Diana Kirkbride, Antiquity, XLII, p270, 1968 AD)

a. “The corridor buildings of Levels II and III naturally provide the major part of the finds and with each season further evidence for their workshop character is revealed. Besides the inevitable flints these buildings yield objects in varying proportions which suggest a certain degree of specialization m the crafts, if one can assume that the buildings belonged to certain families. One unit may show evidence for the practice of a specific craft or crafts while the contents of others are more general. For instance, Complex X contained a preponderance of ground stone tools, principally grinders, though with some pestles, axes and fragments of querns or mortars in addition to a small selection of bone tools and a few beads. On the other hand Complex XIII not only contained a great many grinders, pestles and both ground and chipped stone axes, but to a certain extent it was a bone-tool maker's and to a lesser degree, a bead-maker's factory. The floor was thickly covered with bones and one horned skull lay on a work table (PL XIV B), while by the door there was a spectacular series of shoulder blade shovels and some fine horned heads. Scattered around in the occupation debris were a number of beads, both finished and unfinished; for example cowries with slits across the dome in preparation for its removal and there were several carved stones. The building seems to have been a general emporium with the accent on bone working. Nearby, and probably contemporary, Complex XIV was obviously the workshop of a specialist m bone tools and beads only. In it we found bone stone and shell beads in every stage of preparation. Among others there were small discs of (?) agate and one large one, the latter abandoned with the process of grinding unfinished; green stone (? apatite) barrel and flat discs or bean-shaped beads, some with perforations just begun and others finished, ground and polished. There were mother-of-pearl, cowries, mollusk and bivalve shells, some pierced and one with the boring incomplete. Bone beads were also present in every stage of the making. One long slender tibia, minus the joints, lay beside a slab table, the shaft divided by carved grooves into fairly even slices. Near by were separated slices or discs, rough and unworked and also the finished products, shaped, smoothed and polished. We found one complete bracelet of similar bone beads in another house. The bone tools also provided a fine cross-section of the maker's art; beautiful polished spatulae, slender points and long (?) weaving tools made on worked ribs probably of an aurochs. Raw material, mostly of large (?) aurochs' ribs, tibiae and shoulder-blades lay on tables or in the corridor with a shoulder blade shovel by the door and a trowel or scoop fashioned from an auroch's tibia by one of the many tables. In addition we found the tools used in the manufacture of these articles and blocks of haematite and pumice which must have been used to shape them. Level III examples of this specialization of crafts in certain workshops have already been described; we found a bone-tool maker's workshop, as yet only half excavated; and a 'butcher's shop,'. where there was a whole room full of animal bones, Joints and heads and m the room opposite a mass of heavy tools.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p24, 1966 AD)

b. “The corridor buildings have been described many times. They consist essentially of a narrow, 1 metre, central corridor about 6 metres long from which open six rooms arranged m three opposing pairs. The rooms, only c. 1.5 x 1 metres, are d1v1ded from each other by wide baulks which in some cases are wider than the rooms themselves (Pl. II B). All the buildings are semi-subterranean and are entered by three descending stone steps. In some cases the floors were plastered but never is there a trace of a high-silled hearth. The finds made in the corridor buildings have consistently given the impression, to which weighty evidence is added with each season, that they were workshops rather than dwellings. The fill in these buildings contains implements and waste, lumps of clay, sometimes heavy objects such as querns or grinders, and in nearly every case fragments of plaster, usually painted red. These give every appearance of having fallen from above and we have already conjectured that grinding may have taken place on flat roofs and that the ceilings of the corridor rooms were sometimes covered with red painted plaster.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p14, 1966 AD)

C. OUR REINTERPRETATION OF THE ARCHEOLOGY: Two occupational phases and down-dating:

1. Byrd’s 3 Neolithic occupational phases of Beidha: A, B, C

a. Byrd makes this important disclaimer about his theory of occupation: "The history of the village presented in this volume, however, is simply a model. It should not be considered a precise representation of how the village changed over time." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- Brian Byrd has theorized that Beidha had a Natufian occupation around 11,000 BP and three Neolithic occupational phases around 7000 BC. The problem is that, like most archeologists, he forgot to read his Bible and realize that there is no archeology on earth today that is older than 3298 BC when the flood occurred. Therefore the facts of archeology from the Natufian and Neolithic occupations must need to squeezed into a period of about 3298 BC down to about 1400 BC.

c. Byrd suggests that Beidha has a Natufian period of occupation around 9000 BC, followed by a period of abandonment. Then between 7000 - 5000 BC a Neolithic period of occupation occurred with three phases followed by abandonment until the site was developed by the Nabataeans about the time of Christ (300 BC - 100 AD)

- "Occupation History: The fieldwork revealed that Beidha is a multicomponent site with three discrete periods of habitation: an early Natufian encampment (primarily during the 11th millennium BC); a PPNB village (primarily during the 7th millennium BC); and, ultimately, terraced Nabatean agricultural fields (during the 1st millennium AD). (All dates in this report are in uncalibrated radiocarbon years before 1950.) A considerable hiatus separates each of these occupations (Fig. 34)." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- Top plans: The three periods or "Phases"

of occupation according to Byrd:

- Stratigraphic view of Horizontal plans: The three

periods or "Phases" of occupation according to Byrd:

2. Summary of our interpretation in contrast to Byrd's:

- It is important to understand that we do not question the facts of what archeology has uncovered. Byrd's top plans and aerial stratigraphic maps which he generated from the notes of Diana Kirkbride below are the facts of science.

- Christians don’t question dinosaur bones excavated by Evolutionists; they simply reject the interpretation that the bones are 40 million years old. Likewise, it is the interpretation, timing and sequencing of the facts of archeology that we question, not the tangible results of excavation.

|

Item |

Byrd's interpretation |

Our interpretation |

|

Earliest possible occupation |

Natufian: 9000 BC |

3298 BC: The flood (Gen 6) |

|

Natufian occupation: |

9000 BC |

Possible: During the Ubaid 3 expansion in 3000 BC Likely: During the Uruk 3 expansion, immediately after the Tower of Babel in 2850 BC. |

|

Neolithic Dates |

7000-5000 BC |

Possible: 3298-1406 BC Likely: Round city: 2400 BC. Rectangular city: 1446 BC. |

|

Neolithic Phases |

Three: A, B, C |

Two phases: A+B, C Phase 1 = A+B = round city Phase 2 = C = rectangular city |

|

Round buildings |

Neolithic village (Phase A, B) |

Time of Abraham: Phase 1 |

|

Squarish buildings |

Neolithic village (Phase C) |

Time of Moses: Phase 2 |

|

Destruction of round buildings |

Unknown |

Israelites may have burned and destroyed when they arrived at Kadesh or it may have been burned hundreds of years earlier. |

|

Construction of square buildings` |

Unknown |

Moses in 1444 BC |

|

Square buildings use |

single family dwellings |

Tool factory and grain/manna grinding facility for a larger tented population of 3.5 million Hebrews in the surrounding Petra area. |

3. Our interpretation of two Neolithic PPN occupation phases:

a. Our PPN phase 1 dates to the time of Abraham and our phase two dates to the time of Moses. Byrd sees three Neolithic PPN occupational phases (A, B, C) that date to ~6500 BC, but we see only two.

- A is oldest, C is youngest: "The Phasing Model: The resulting model of the Beidha Neolithic occupation history consisted of three phases, labeled from earliest to latest (A through C). The model was based primarily on the relative stratigraphic relationships between buildings, particularly with respect to construction events " (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- "Summary: The site of Beidha is situated on and within a remnant terrace formed by alluviation that began during the Late Pleistocene and ceased prior to the ninth millennium BP. Three periods of human occupation are present - Natufian, Neolithic, and Nabatean - with lengthy time periods devoid of occupation separating them. This resulted in a thick sequence of cultural and noncultural deposits up to 6 m in depth." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- However, we feel that in spite of Byrd's good work, that there is good reason to argue for two occupational phases: First: A + B and Second: C. The reason is because if you add A to B the buildings create a perfect and complete village. A and B are like to sections of a puzzle that fit perfectly together with little overlap of buildings. A + B are also round buildings whereas C are square. C is also built above and on top of A + B.

- Byrd documents how the buildings of A+B did not overlie or overlap each other. This is evidence that A + B were the same occupation level. He of course would reject our theory of two occupation levels: "Buildings from each of the three phases do not stratigraphically overlie one another across the entire site (Fig. 40). There are a number of reasons for this situation: the site was never entirely covered with inhabited buildings and other portions of the site consisted of courtyards and no doubt abandoned, decaying structures; new construction often totally destroyed evidence of earlier buildings; and the location of courtyards varied some-what over time. It is more plausible that the tell built up slowly and unevenly." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- Byrd openly considers the idea that the phases A and B are contemporaneous or that B and C are contemporaneous: "Could the subphase A2 buildings at the southern end of the site, where no phase B buildings occur, actually be contemporaneous with phase B? And what about the northeast cluster of five phase B buildings that are not clearly overlain stratigraphically by phase C buildings: could they be coeval with phase C? Although these alternative reconstructions are plausible, they are considered less likely. Many more questions could be posed with respect to the phasing, some of which cannot be answered with the available evidence. ... The phasing model represents what I consider to be the best, idealized representation of how the Neolithic village of Beidha changed over time. The model is viable, however, even if there are only a few concrete examples where buildings from each phase directly overlie each other. Three locales furnish such evidence (Fig. 39). Two examples were located in the south half of the tell: the well-documented sequence of buildings 41-56-43-12/19 in the center of the southern area (Fig. 454, later Fig. 74); and the superposition of building remnants 17-33-15-11 along the eastern edge of the site. Both of these examples of superpositioning include buildings from the upper two phases (B and C) and subphases Al and A2. The only instance in the northern portion of the site where all three phases are stratigraphically sequential occurred in the central area with the building sequence 30-29-82-8 (Fig. 454). These examples, although limited in areal scope, provide vivid testimony of the phasing model validity. A detailed presentation of the stratigraphy and phasing of the tell is contained in the following chapter." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

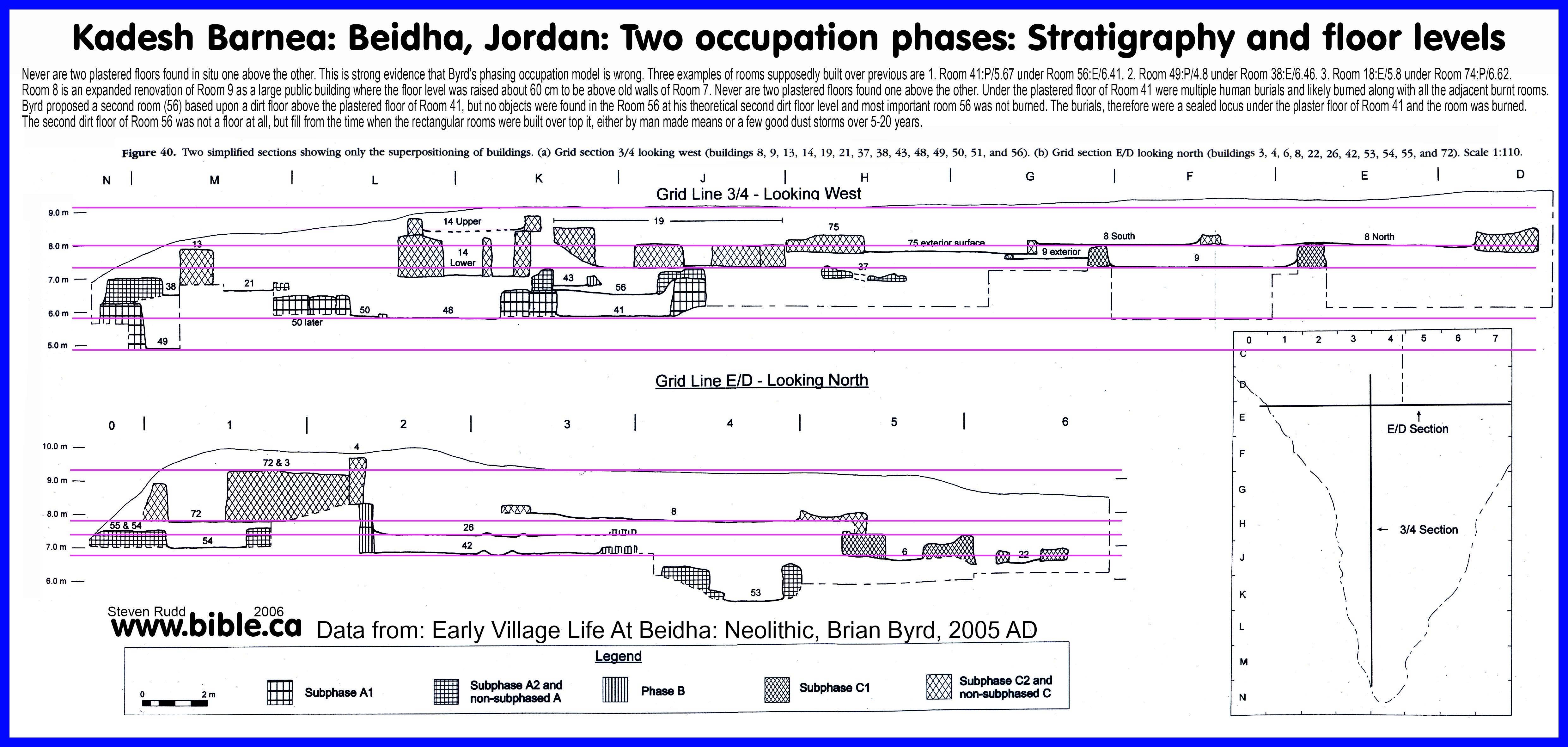

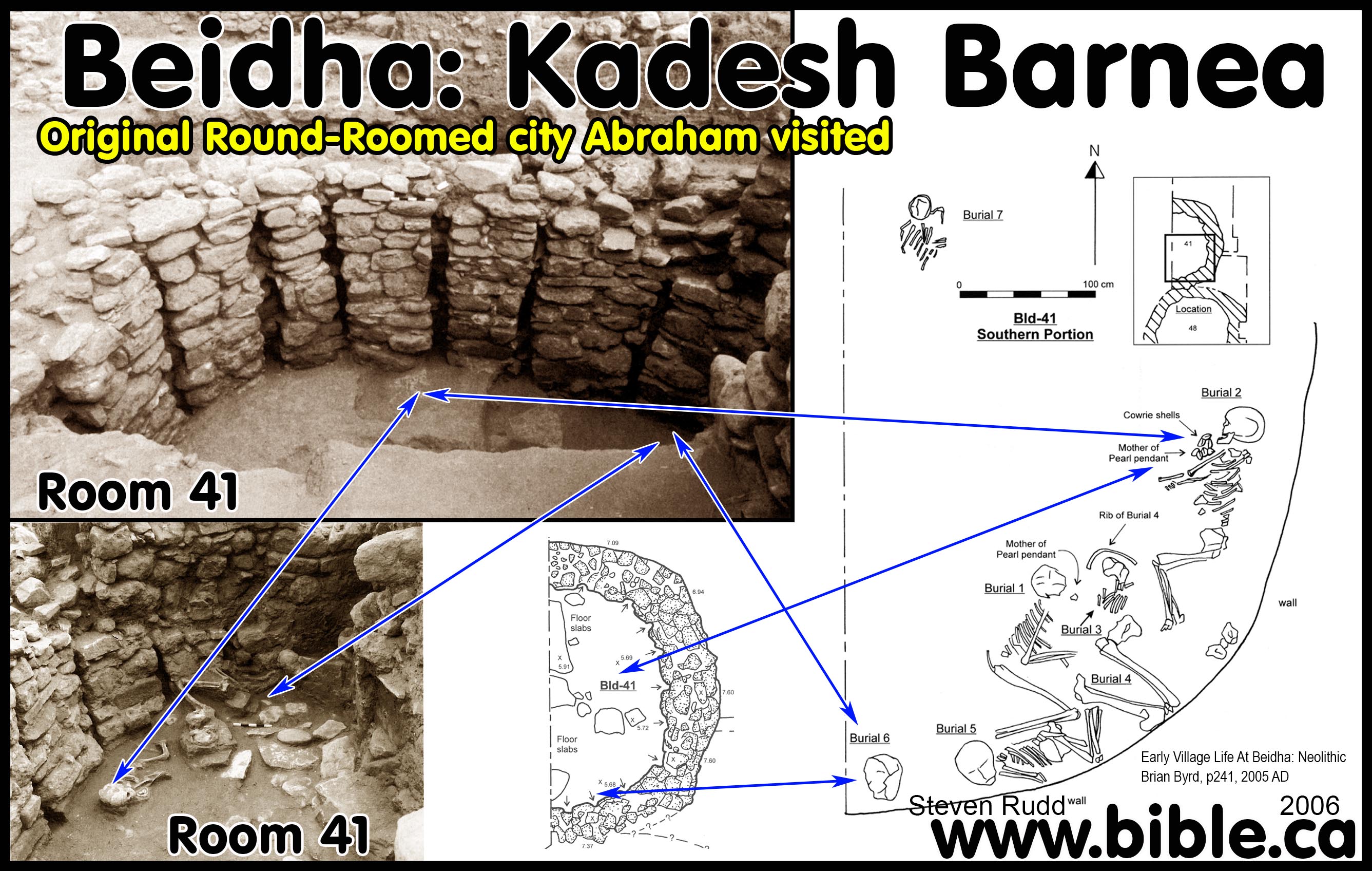

4. CRITCAL OBSERVATION: Never are two plastered floors found in situ one above the other.

a. Byrd interprets that Phase B Buildings were built directly upon phase A, but this is wrong for several reasons.

b. This is strong evidence that Byrd’s phasing occupation model is wrong. There are only three examples of round rooms supposedly built over previous round rooms: Note: Elevations are measured from a low benchmark upwards, not sea levels, so the stratigraphy appears confusing unless you understand their excavation methods.

1)

Round Room 41 (Plastered

floor with elevation 5.67m) under Round

Room 56

(Earth floor with elevation 6.41m). Under the plastered floor of Room 41 were

multiple human burials and likely burned along with all the adjacent burnt

rooms. Byrd proposed a second room (56) based upon a dirt floor above the

plastered floor of Room 41, but no objects were found in the Room 56 at his

theoretical second dirt floor level and most important room 56 was not burned.

The burials, therefore were a sealed locus under the plaster floor of Room 41

and the room was burned. The second dirt floor of Room 56 was not a floor at

all, but fill from the time when the rectangular rooms were built over top it,

either by man-made means or a few good dust storms over 5-20 years.

2) Round Room 49 (Plastered floor with elevation 4.8m) under Round Room 38 (Earth floor with elevation 6.46m).

3) Round Room 18 (Earth floor with elevation 5.8m) under Round Room 74 (Plastered floor with elevation 6.62m).

4) Rectangular Large Room 9 (Plastered floor 7.98m) under Rectangular Large Room 8 (Plastered floor 7.4m). Room 8 is an enlarged renovation of Room 9, built over top of several previously constructed rectangular buildings on the east wall. In order to minimize construction, the floor level of the new Room 8 was raised 58 cm. The expanded eastern section of the renovated floor was built directly over top of the old walls of Rectangular Room 7. Wall stone removed from the walls of Room 7 was then used to construct a double width wall for the new Room 8.

c. Never are two in situ plastered floors found one above the other in the round rooms. There are two plastered floors, one on top of the other, in the rectangular city, but this was the large central room that was simply enlarged shortly after the original rectangular city was constructed from a master blueprint.

d. When all round rooms are overlaid on top of each other, it creates one complete city.

5. We have taken the six occupation maps from Byrd and combined them into two overlays to create a virtual representation of our two phases. Notice all the round rooms fit together like a jigsaw puzzle when they are overlaid one atop of the other. The same is true with the rectangular roomed city. As we have already seen, only three round rooms were interpreted to be built directly upon older round rooms but there is only one plaster floor excavated. If two in situ plastered floors, were found in the round city, this would provide evidence of two different rooms. But remember, the walls of the round rooms in all of Byrd’s phases almost never encroach on another room.

b. "Many buildings in phase C (and probably in phase A) were no doubt contemporaneous." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

Phase 1: 2800-1444 BC

Our "Phase 1" is equal to Byrd's Phase A1 + A2 + B. You will notice that all the buildings are round, are built basically on the same continuous ground level and fit together like puzzle pieces. Basement elevations varied from room to room but this simply shows that some basements were dug deeper than others from the same ground level. Buildings may have had new walls built, but these were always directly on top of old foundations. We suggest that these round Phase 1 buildings existed at the time of Abraham and continued to be occupied until Moses arrived and destroyed them by burning in 1444 BC at the exodus. If Moses did not destroy the city, it could have happened earlier before arrival.

Phase 2: 1444-1440 BC

Our "Phase 2"is equal to Byrd's Phase C1 + C2 + 2nd floor. You will notice that these buildings are square, are built basically on the same ground level fit together like puzzle pieces. There is evidence of renovations of these square buildings primarily in Rooms 7 and 8. These buildings were built less than 50 cm directly on top of Phase 1 round buildings. It is as if Moses buried the round buildings of Phase 1 and built directly on top of a new grade level that was 50 cm above the old round city. These rectangular buildings did not experience burning. A pre-planned mass abandonment is indicated because many of the doors of the rooms were bricked up. The Nabataeans came along between 300 BC and 100 AD and built terraces on the surface and carved all the tombs in the rock cliffs we see today.

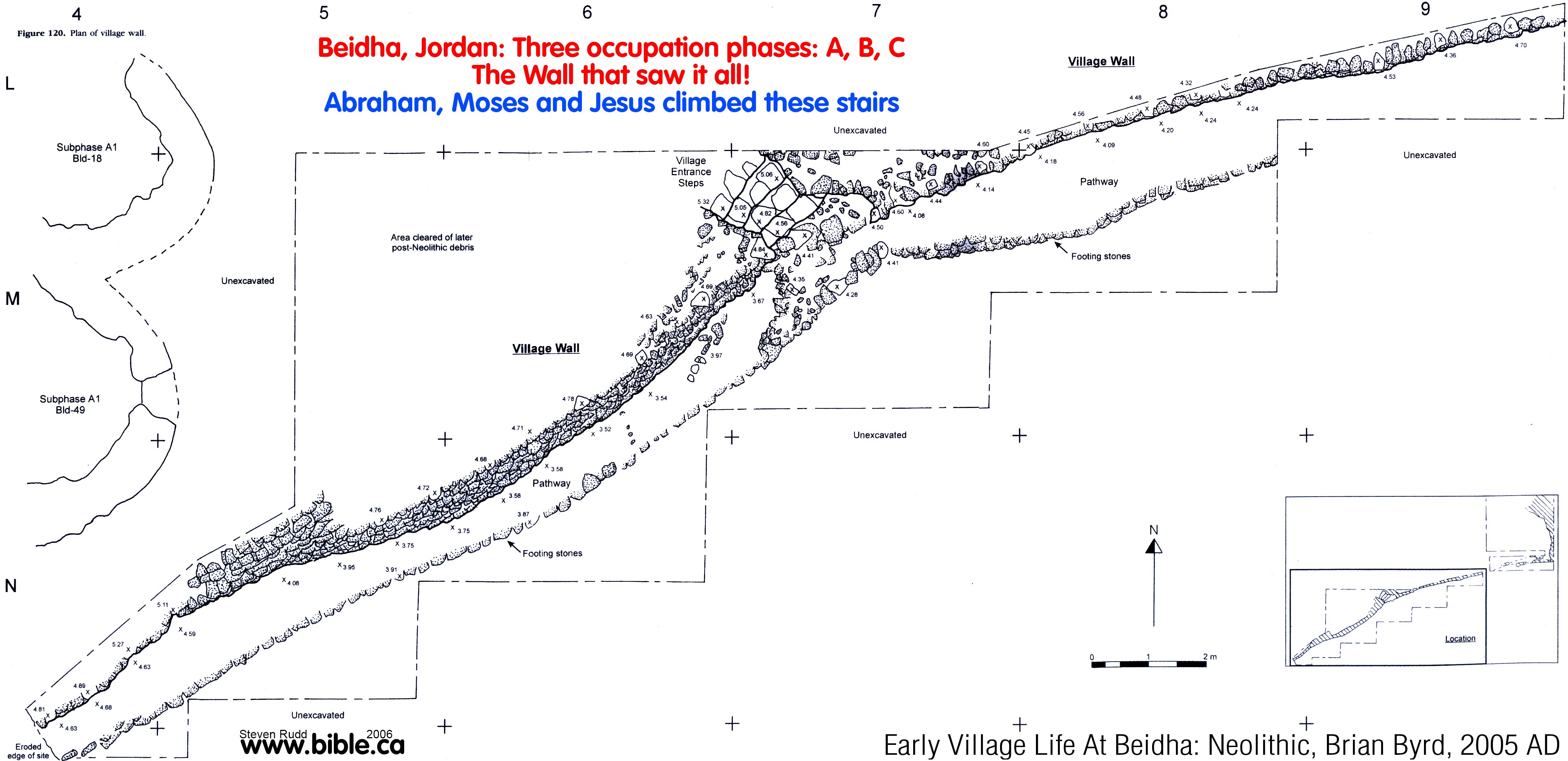

D. The Village Retaining Wall that saw it all!

Abraham, Moses and Jesus may have climbed

these stairs!

1.

When you do a detailed study of the archeology at Beidha, you are struck

with the fact that only one feature remained the same throughout all three

"Neolithic" occupational phases: The wall and stairs! The wall is in

fact, what preserved the entire archeological tel from water erosion from the

wadi that passes directly by the city. In ancient times, this would have been

their water supply. This wall would have been visible in the first century. The

entire Petra area was later developed by the Nabataeans. If the wall and stairs

were retained or used by the Nabataeans, then Jesus may have also walked these

stairs, for he would have most certainly visited Nabataean Petra in his

lifetime.

2. "The original western edge of the tell, of course, is unknown, since erosion by the Seyl Aqlat has destroyed it." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

3. "Neolithic Village: An impressive Neolithic retaining wall, with steps leading into the village, lies along this edge of the site (Figs 31-32). Its function was, no doubt, primarily to retard continued erosion, and it appears to have been constructed during the initial phase of occupation." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

4. "Despite the extensive distribution of phase C buildings, building superpositioning was rare and subphases were not distinguished. Two highlights from these excavations included the exposure of a village wall and associated steps leading up into the settlement from the south, and the best preserved example of an upper story from a phase C corridor building (14)." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

5. "The southern enclosing wall of the village was probably built during this initial occupation (Figs 39, 42, 69). Although this assertion cannot be demonstrated conclusively, due to post-Neolithic disturbance, the similarity in absolute elevation of the top step of the village wall and the exterior base of buildings 18, 41, and 48 supports this assertion (Fig. 32). The village wall may have remained in existence throughout the history of the village. Moreover, the height of the village wall was raised at least once, as deposits built up within the village itself." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

6. "Village Wall Excavations: The preserved height of the main village wall ranged from 1.0 m to 2.2 m west of the steps, and only a few courses remained east of the steps. Directly west and east of the steps, footing stones and a probable path were preserved along the base of the wall. The village wall was constructed during phase A, remodeled several times, and probably remained in use throughout the occupation span of the village." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

7. "The village terrace wall and associated entrance stairs were probably constructed along the south edge of the site during phase A." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

E. Plastered floors, Red perimeter painted floor, Four courses of mud bricks found:

1. “Plaster. Two kinds of plaster for floors and walls were used at Beidha. Their content has not yet been analysed so only visual descriptions can be given here. As far as the evidence for the earlier periods goes at present, Levels VI to IV contain plaster of a predominantly sandy clay mixture in which there is a strong trough not very visible element of lime. The individual layers are paper thin but because the wall plaster is very fragmentary the largest area examined was under 50 x 30 cm., found in a burnt polygonal house. Here it seemed that colour was applied to some of the plaster layers near the wall surface and subsequently covered by many layers of plain plaster. Traces of the following colours were found: a purple-red, ochre red and brown; another layer had two smeared black lines and yet another two red traces on a greyish slightly green surface. These pieces are very small but the sum of the evidence on the plaster so far indicates that most of the painting was a simple outlining of features in broad bands and dados.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p22, 1966 AD)

2. “On excavation we found that the plaster floor of the former had been relaid five times and not four as previously reported. Each floor was composed of many thin layers of plaster and ran to an interior wall face that was founded slightly in front of, or behind its predecessor but despite this shifting of position the dimensions of the room (9 x 7 metres) remained the same. The band of red painted plaster was another constant feature although not on every layer of plaster. In the second main floor from the top the western third of the room was taken up by an irregular series of roughly circular holes of varying sizes (Pl. V B) and two short, straight, parallel ones (Pl. VI A). These were cut down through the underlying plaster floors although with a single exception there were no similar installations in the topmost floor. These holes must have been related to some kind of fittings, probably of wood or stone and were packed with broken angular stones probably to prevent the upper floor from collapsing at these places. Their use defies interpretation at present. All five floor levels were very clean and scarcely a waste flake was found.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p17, 1966 AD)

3. Building 9: “The building floor consisted of a gravel base with a plastered surface that was refloored several times. Red bands were apparently painted around the edge of the floor, the stone basin, and the hearth. Several features were associated with the floor including a hearth and two postholes.” (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, p56, 2005 AD)

4. “The next to last of these thin resurfacings (and several others prior to it) contained painted decoration on the floor and wall of the northern room. A 30-cm-wide band of red paint ran along the edge of the floor and up onto the walls (Fig. 412). The decoration was best preserved on the south wall and on the floor (except in a portion of the badly disturbed eastern section). A red band of paint also outlined the hearth, the stone-lined pit, and the stone basin location. This pattern of painting was similar to that of earlier large building 9.” (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, p69, 2005 AD)

- "Excavations in a sounding below the floor of subphase Al, building 18, identified an architectural feature con-structed of mudbrick with a thin plaster facing (Fig. 61). It should be noted that the exact constituents of all the plaster used at Beidha and variation in its manufacture are currently unknown. At least four courses of a mudbrick wall were preserved, and the wall appeared to exceed a meter in thickness (see also Kirkbride 1967: fig. 2). The occupational debris associated with this facility, labeled deposit L4:91, was originally classified as Natufian (Kirkbride 1967: 10). That assessment is no longer tenable after reexamination of the small sample of lithics that were recovered (Byrd 1989b: 21). The lithics appear to be Neolithic in age and may well predate the middle PPNB, but precise determination must await further field investigations and a larger sample size." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- "Remnants of mudbrick were also reported by Kirkbride-Helbxk (Kirkbride 1967: 10-11) outside of building 48 and building 37. The latter was reported as containing "a mud-brick wall nearly a meter high, on a curving stone foundation." (Kirkbride 1967: 10). Unfortunately, these two discoveries lack adequate archival documentation and nothing further can be presented regarding their stratigraphic relationship and character." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

- "Exterior courtyard deposits represent the earliest occupation deposits documented for phase A. These include plastered surfaces, ramadas/verandas, and possible mudbrick construction. The initial stone buildings of subphase Al were semisubterranean, with their floors up to 50 cm below the outside ground level. They were circular to oval in plan, and erected around an inner skeleton of posts and beams. To this inner skeleton was added a wide stone wall with short, straight segments of its inner face built against the posts. This created a thick curving wall with its inner face broken at regular intervals by the vertical slits that held the posts. The wall and slits were then plastered over to provide a smooth interior face, and based on evidence from burned buildings, the ceilings were also plastered. Individual structures often shared walls where their curvilinear plans converged." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

F. “H” shaped rooms for a Tool factory and communal crop storage not residential dwellings:

1. It is clear from the finds in the work rooms that this was a commercial manufacturing and mass grain grinding city:

a. Bone, stone and seashell tools and jewelry were found in the workshops in every stage of production.

b. A large number of grinders were found in the city indicating commercial levels of mass food production like grains and possibly Manna.

c. The “H” shaped rooms were small and odd shaped. The branches were often about 1 meter wide. These smaller “H” shaped rooms were not suitable for homes and were clearly used for storage and production.

2. After the round roomed Phase A + B was destroyed by the Hebrews when they arrived at Kadesh (or before they arrived), a new and unique type of large public storage buildings and tool manufacturing factory were built:

a. "A new style of architecture began in phase C and was used throughout the settlement. This novel corridor building architecture appeared fully developed without antecedents at the start of phase C. It was a distinctive technological and organizational development comprised of two internally subdivided stories - one as a basement and the other set slightly above ground level. Each story had a separate entrance. The upper stories were open in plan and had plastered floors. In contrast, the basements were comprised of multiple small rooms, with a variety of features (except hearths) within them, and had earthen floors. Several single-story quadrilateral buildings (both large and small), coexisted with these corridor buildings and provide evidence of continuity with earlier architectural traditions." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

3. Byrd, of course, sees all the Phase C buildings as single family dwellings (residences). We feel that these buildings are in fact public storage and work buildings for the larger 3.5 million Hebrews that are living in tents in the area.

a. "The establishment of two-story corridor buildings in phase C entailed virtually a three-fold increase in the interior area of domestic units. This size increase accompanied an expansion in the structural organization of individual dwellings and related household activities. This does not indicate an intrinsic change in the size of these households: nuclear families probably still constituted the fundamental domestic unit. The addition of basements to domestic dwellings allowed for storage and many household production activities to take place within spatially segregated small rooms within the dwelling. The upper stories of these dwellings were more open spatially and structurally and were no doubt the venue for eating, sleeping, and entertaining. The range and emphasis of activities varied little between households. The main exception to this pattern involved specialized production of personal adornment items in one dwelling (notably marine shell jewelry). This may indicate some preferential access to luxury items existed between households." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

4. Byrd notes that the "houses" became more adapted for storage. He theorizes that this is because each family started becoming independent of the community they lived in. In other words, private ownership and individuals storing their own crops for themselves in their own houses for their own private use to the exclusion of the community. However out theory is equally valid: These were not houses, but public storage buildings for a larger Jewish community living in tents in the general area of Kadesh Barnea.

5. Byrd himself has determined that the "Eastern Sector" was comprised of public buildings that served a larger population, not houses for a family to live in:

a. "Although there is no evidence to demonstrate that more than one was ever occupied at once (except possibly during phase B), additional corporate units could have existed in the western, now eroded portion of the site. Other nondomestic buildings were situated to the east of the tell. They shared little in common with the domestic dwellings within the community, except their size; instead they had many unique structural elements and had more in common with the corporate structures within the village." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

6. The rectangular phase C buildings not only had separate basements only accessible from the outside, not inside, but the second floors between two different buildings, were connected with doorways! The second floors of different buildings were built beside each other, shared outside walls and were like large office areas all connected from the inside:

a. "Major changes in the organizational character of the corporate building occurred during the final subphase of the occupation. This nondomestic building was significantly larger than previous ones and structurally more elaborate, consisting of two large rooms with a number of associated features (including a stone monolith). Unlike earlier corporate buildings, this one was refurbished at least four times, and each remodeling entailed a substantial investment in labor and supplies. Its interrelationship with adjacent buildings and open space also differed considerably from previous corporate buildings. This included an entrance into the corporate building from the upper story of an adjacent domestic building. In addition, the building overlooked the main central courtyard and during its use life this courtyard became an enclosed space with small storage units." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

b. "These developments were matched by elaboration in the spatial organization of production activities and storage within domestic dwellings, suggesting household autonomy increased over time. Interior features became more frequent, interior space more compartmentalized, and activities and storage were thus focused in discrete localities. Ultimately, the introduction of more structurally complex two-story dwellings with subdivided basements and separate entrances facilitated the spatial discreteness of production and storage activities within the context of individual buildings. The second organizational trend, more formal and institutionalized mechanisms for integrating the community, was confirmed by the introduction and persistence of distinct, large nondomestic buildings. They were interpreted as the location for suprahousehold decision making and ceremonial activities, and the role and importance of such corporate activities increased during the occupation span of the community based on their increased size and structural elaboration." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

7. The basements of the Phase C buildings could not be accessed from the main floor. Instead the basements were accessed from the outside. This is clear evidence, in our view that the Phase C buildings were not residences but storage buildings for a larger population of Hebrews at Kadesh Barnea: "Over time, the distinction between private and public space increased, and production activities and storage were increasingly carried out within individual dwellings. In phase C, production and storage were concentrated in household basements that had restricted access and were not directly connected to the upper-story living areas." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

G. Jericho and Beidha:

- The sequence of continuous occupation at Beidha is unique in the Levant. Similarities exist between the round buildings at Beidha and Jericho because at both sites, round buildings were replaced by square ones.

- At Jericho, it is not clear if the round or later square buildings were destroyed by the Hebrews during the conquest in 1406 BC.

- But Joshua placed a curse upon the city and it appears to have not been rebuilt until the time of Hiel in 860 BC: Jericho continued to be occupied down to the time of Jesus: "Then Joshua made them take an oath at that time, saying, "Cursed before the Lord is the man who rises up and builds this city Jericho; with the loss of his firstborn he shall lay its foundation, and with the loss of his youngest son he shall set up its gates."" Joshua 6:26 "In his days Hiel the Bethelite built Jericho; he laid its foundations with the loss of Abiram his firstborn, and set up its gates with the loss of his youngest son Segub, according to the word of the Lord, which He spoke by Joshua the son of Nun." 1 Kings 16:34. "He entered Jericho and was passing through. And there was a man called by the name of Zaccheus; he was a chief tax collector and he was rich." Luke 19:1-2.

- "PPNB: Beidha is currently the only southern Levantine site that documents this transition in residential architecture. Elsewhere in the southern Levant, the transition is either completely abrupt without transitional steps (such as at Jericho) or else PPNB sites have either curvilinear or rectangular architecture (Byrd 2000). At Jericho, largely undifferentiated PPNA curvilinear buildings were abruptly replaced by PPNB rectangular pier houses considerably earlier than rectangular buildings were first constructed at Beidha (Kenyon 1981). The pier-house style of architecture was then used over a wide area of the southern Levant during the PPNB and was well suited to be internally subdivided (Byrd and Banning 1988)." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD, Conclusion)

- The transition from round buildings to rectangular at Jericho is important. If the rectangular buildings were destroyed at the time of Joshua, this shows that such architectural designs were in current use while Joshua was at Kadesh Barnea.

H. Phase A was burned, Phase C abandoned after doors were bricked up:

1. “The problem of how the semi-basement workshops were lighted has not yet been solved. If there was an upper storey then the only light seem; to have come from doorways; this was occasionally augmented by lamps in the form of rough stone bowls bearing traces of carbon, but these lamps are rare. There is no evidence for proper doors, no stone with swivel-holes apart from a single re-used quern, so in all probability the inhabitants used skins as a temporary measure when necessary. In many cases buildings were found with their doors closed by rough stone walls built inside the apertures but whether this was because the occupants left meaning to return, or whether this door-closing was part of a ritual performed when a house was to be rebuilt cannot be ascertained. In view of the close levels of occupation and no apparent break in their continuity the latter explanation is the more probable. One other peculiarity at Beidha is the lack of parching ovens. Not a single oven has been found in any level in the whole excavated area.” (Five Seasons at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Village of Beidha in Jordan, Diana Kirkbride, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol 98, p16, 1966 AD)

2. "It cannot be conclusively demonstrated whether the abandonment of the village was sudden or slow, but patterning in trash dumping within buildings suggests that it was a gradual process [guess by Byrd]." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

3. "Phase A included the initial, founding occupation of the PPNB village through the burning and abandonment of a series of round buildings in the southern sector. Subphase Al buildings were semisubterranean and erected around an inner skeleton of posts and beams. In contrast, some subsequent subphase A2 buildings appear to have been built above ground and no longer utilized the post-socket construction. Phase B was poorly preserved in many areas of the tell due to later phase C construction. Phase B architecture included subrectangular buildings with straighter walls and rounded corners that were typically single-roomed, freestanding, and semisubterranean. The final period of occupation, phase C, was dominated by two-story, rectangular corridor buildings. The upper stories were poorly preserved, while lower stories were semisubterranean and included a central corridor and a series of small basement rooms. The construction of a very large building on top of a series of phase C corridor buildings enabled two subphases to be distinguished in a portion of the tell. ... Large-scale abandonment of buildings may have occurred at the end of phase A based on the burning of a considerable number of structures. In contrast, the upper deposits of phase B were largely destroyed by subsequent phase C construction." (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

4. “The Wadi el Ghurab has both deposited fill during large floods and eroded away materials over time: "Natufian Encampment: The Natufian occupation at Beidha took place during an aggradation period of the Wadi el Ghurab (Field 1989: 86-90). The sediment that comprises the Natufian occupation was largely deposited by streams with limited cultural input. Throughout the wadi, the level of the valley floor was considerably higher during the Natufian occupation than today. ... The Natufian may well have extended a considerable distance both to the south and west, but erosion has destroyed any such evidence. ... The site appears to have been abandoned for approximately 3,500 years, during which time more than 1.5 m of noncultural sediment was deposited, separating the Natufian from the subsequent PPNB village.” (Early Village Life At Beidha: Neolithic, Brian Byrd, 2005 AD)

Conclusion:

- From scripture and ancient literary sources, we know that Kadesh Beidha was located at or near Petra, Jordan.

- Biblical Kadesh Barnea, Sela, Joktheel, En-mishpat, was visited by Abraham in Gen 14 and Moses in 1444 BC

- We would expect a large population of 3.5 million Hebrews to easily occupy land that is 20 km long.

- El Beidha is located 5 km north of Petra where commercial levels of grinding wheat, rye and possibly Manna took place. It is important to note that no fires were excavated in the rectangular buildings proving these were workshops for tool production and food storage not houses for domestic dwelling.

- Basta is located 12 km SE of Petra which functioned as a mass crop storage and drying area. Additionally, Basta was a commercial level meat packing plant where the three large rooms featured subterranean channels to keep the floors dry and cool. Additionally, fire places were located in each of the three large rooms where the meat was hanging to control damage by flies and maggots. A large assemble of 100,000 Kosher bones was excavated on the floors of the rooms.

- We theorize that there are two phases of occupation at Beidha, not three as Byrd suggests.

- The first phase of occupation is represented in combining Byrd’s phase A + B. The buildings of this period were round. This first period of occupation would date back to the time of Abraham.

- The second phase of occupation is represented Byrd’s phase C. Perhaps the phase C square buildings are where Moses lived while at Kadesh for 38 years as a central hub of organization for Israel in the wilderness. A theory yes, but not unreasonable.

- Beidha and Basta share many similarities:

a. First, both Basta and Beidha share a close geographic proximity. Basta is a short distance from Petra as you follow a large natural valley between the two cities. Topographically the two cities are connected by the natural terrain.

b. Second, It is clear that a large, well organized population arrived and founded both Beidha and Basta from a master blueprint plan. Both cities appear to be industrial, work centres that were not intended for residential dwelling. Based upon simple population dynamics in this part of the world, the earliest possible occupation date for both cities is after the Tower of Babel in 2850 BC in spite of the sites designation as PPN at 6500 BC. Basta and Beidha were both large industrial cities that served a large, well organized population and not used for residential dwellings.

c. Third, both Basta and Beidha feature rectangular-shaped buildings with red painted plaster floors

d. Fourth, both Beidha and Basta feature a large central room surrounded by smaller rectangular rooms.

e. Fifth, both Basta and Beidha were large scale commercial operations without residential domestic dwellings. They were work centers not living quarters. Basta was a dry food-storage as evidenced by the small 1x1 meter rooms with access windows, a slaughterhouse as evidenced by the massive assemblage of 100,000 kosher bones found in each of the large rooms, subterranean channels under plastered floors which featured fire places for smoke generation in each of the large rooms and a flint production city as evidenced by the massive dump of flint debitage (man-made chips of flint). Beidha was a manufacturing town for tools and jewelry made of bone, flint and seashells as evidenced by the small object finds through excavations on the floors of the various rooms.

f. Sixth, no cult center was identified in the excavations at Basta and Beidha.

g. Seventh, both Basta and Beidha experienced an abrupt, mass abandonment. The doorways of many of the rooms at Beidha were bricked up, sealing the only entrance into the rooms until the time of modern excavation. At Basta, the impressive height of the walls and the sand fill inside the rooms indicates the city was buried after abandoned by the sands soon after abandonment. If the city continued to be occupied, this sand could have easily been dug out and the city re-occupied.

h. Eighth, excavators found no kiln fired ceramics (pottery) at Basta and Beidha. This is why both sites are designated “pre-pottery Neolithic (PPN). However, there are a number of explanations why no pottery was found. Perhaps this was an extension of the miracle of the Hebrew’s clothing and shoes not wearing out for 40 years in the wilderness. Perhaps their pottery was miraculously prevented from breaking as were their shoes from wearing out. Since both cities were specialized industrial work centers wherein little or no food preparation was evidenced, maybe pottery was not in the city because it was not needed. At Beidha, the excavators noted that no firepits, tabuns or hearths were excavated in the entire city. Where there is no fire, there is no food preparation and no need for pottery. At Basta, a few tabun fragments were excavated along with numerous firepits in the large central rooms, but these may have been used to generate smoke to keep flies away from hanging meat and were therefore not used for food preparation.

5. Basta and Beidha are different in several ways:

a. First, while Beidha has one large central room, Basta has three!

b. Second, the surrounding rooms at Basta are much smaller than those at Beidha which were large enough for workshops. Basta had a network of very small cubicles that are 1 x 1 meter with windows at chest height for ventilation and access. These access windows face out into a large common area, but there are also windows between 1x1 meter cubical rooms.

c. Third, Basta was designed with an intricate pre-planned subterranean channel system dug into the floors of many of the rooms and then covered with large cap stones. While the design of covering cap stones resembles ancient drainage channels under the two city gates recently excavated at the 10th century city of Khirbet Qeiyafa, their function is puzzling because the channels “dead end” preventing the free flow of air through the channels or access to the outside. One articulated burial was were made in a channel, likely at the time of original construction. Three more jumbles of human bones were found in another channel with the heads arranged in a triangle pattern, likely put there after construction. Four buried bodies is a tiny number considering the large surrounding population and this indicates that these burials were exceptional. The Excavators concluded these channels were used as insulating air chambers to control moisture on the floor above and/or for burials, but their purpose to them remained a mystery. We propose that these channels were built under slaughter room floors of hanging meat in order to not only control moisture but to also function a fluid drain for liquids. Only the larger rooms had fires AND these subterranean channel networks under the floors. We agree with the excavators that the smaller 1x1 meter cubical rooms with the windows were likely used for mass food storage.

d. Fourth, while no fires, tabuns or hearths of any kind were excavated at Beidha, three large fireplaces was found at Basta, once in each of the three large central rooms. A large ash layer was found in one of the large rooms [number 1] on the surface of the floor in Area B of Basta. These fires were probably used to generate smoke to keep flies away from the hanging, processed meat. These fireplaces showed little evidence of food preparation. Again, only the large rooms at Basta had fires and only the large rooms had the channel network under the floor. It was a slaughterhouse.

e. Fifth, while a large assemblage of 100,000 kosher bones were found inside the large slaughterhouse rooms at Basta, very few bones were found at the tool factory at Beidha.

6. This evidence supports the author’s proposal that both Beidha and Basta might be the actual cities occupied by Moses during the conquest in 1444-1406 BC. This is highly speculative yes, but we are certain that the dating of these two cities by the excavators (6500 BC) is off by at least 3200 years because it cannot predate the flood in 3298 BC. This known error in dating represents up to a 100% deviation from the actual date. More research needs to be done in reexamining the dating of Basta and Beidha and pre-pottery Neolithic sites in general. PPN sites are dated with naturalistic evolutionary thinking and timescales solely on the basis of the lack of pottery. Carbon dating is notoriously inaccurate and must be “adjusted” to fit the presupposed times supplied by the excavators to the labs. Carbon dating labs refuse to do blind testing without verbal input of the final expected date. The author has first-hand evidence of labs requiring in advance of testing, where the sample came from and what is the expected date of the sample. Notice the “uncalibrated date” at Basta was ~6000 Before present which produced a date of about 4000 BC. While this is still impossible, being 700 years before the Noahic flood, it illustrates the nature of Carbon dating since this is still 2500 years too YOUNG to match the presupposed PPN date of 6500 BC and therefore needs to be “calibrated”. “A charcoal date yielded an age of 6055 +/- 255 bp (HV 17192, uncalibrated).” (Basta I The Human Ecology, Gebel, Nissen, p65, 2004 AD)

7. Yes, I am the first person in history to specifically suggest that Beidha is where Kadesh Barnea was located. However, everyone from the time of Josephus, Eusebius down to 100 AD places Kadesh Barnea at Petra or near Petra.

- While it may be considered absurd to suggest that a PPN site was actually occupied during the Early and Late Bronze Ages, we know that the assigned dates of 9000 BC for Natufian and 6500 for PPN is absurd because it predates the creation of earth by 4000 years (5554 BC).

- At least it can be clearly and successfully argued that the archeology of Beidha predates 1000 BC. This is in contrast to the fact that nothing earlier than 1000 BC has been found at Qudeirat, where all Bible maps have unfortunately placed Kadesh Barnea since 1916 AD.

- Based upon Bible study and combining the witness of history, we concluded that Kadesh must be either at Petra or in the general area of Petra. Beidha (and Basta, 12 km SE of Petra), therefore, is the perfect choice, since it is indeed just north of Petra, and it is the only place in the Levant that has a long term, continuous occupation period that predates 1000 BC to the earliest times of Abraham in 2100 BC.

- Further Research:

a. See also Kadesh Barnea.

b. See also Petra.

c. See also Basta: Massive dump of 100,000 bones, possibly from the 38 years at Kadesh Barnea.

Steven Rudd, 2006, October 2019

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.