Ein El-Qudeirat

Fortress of Solomon

950 BC but Cannot be Kadesh Barnea

"The world's unfortunate choice for Kadesh Barnea: 1916 AD -

Present"

"Has the site been correctly

identified?

If so, why have we found no remains from the Exodus period? ...

Thus far our excavations have yielded nothing earlier than the

tenth century B.C. - the time of King Solomon."

(Rudolph

Cohen)

See also: Chronological History of "The search for Kadesh"

|

|

|

|

|||

|

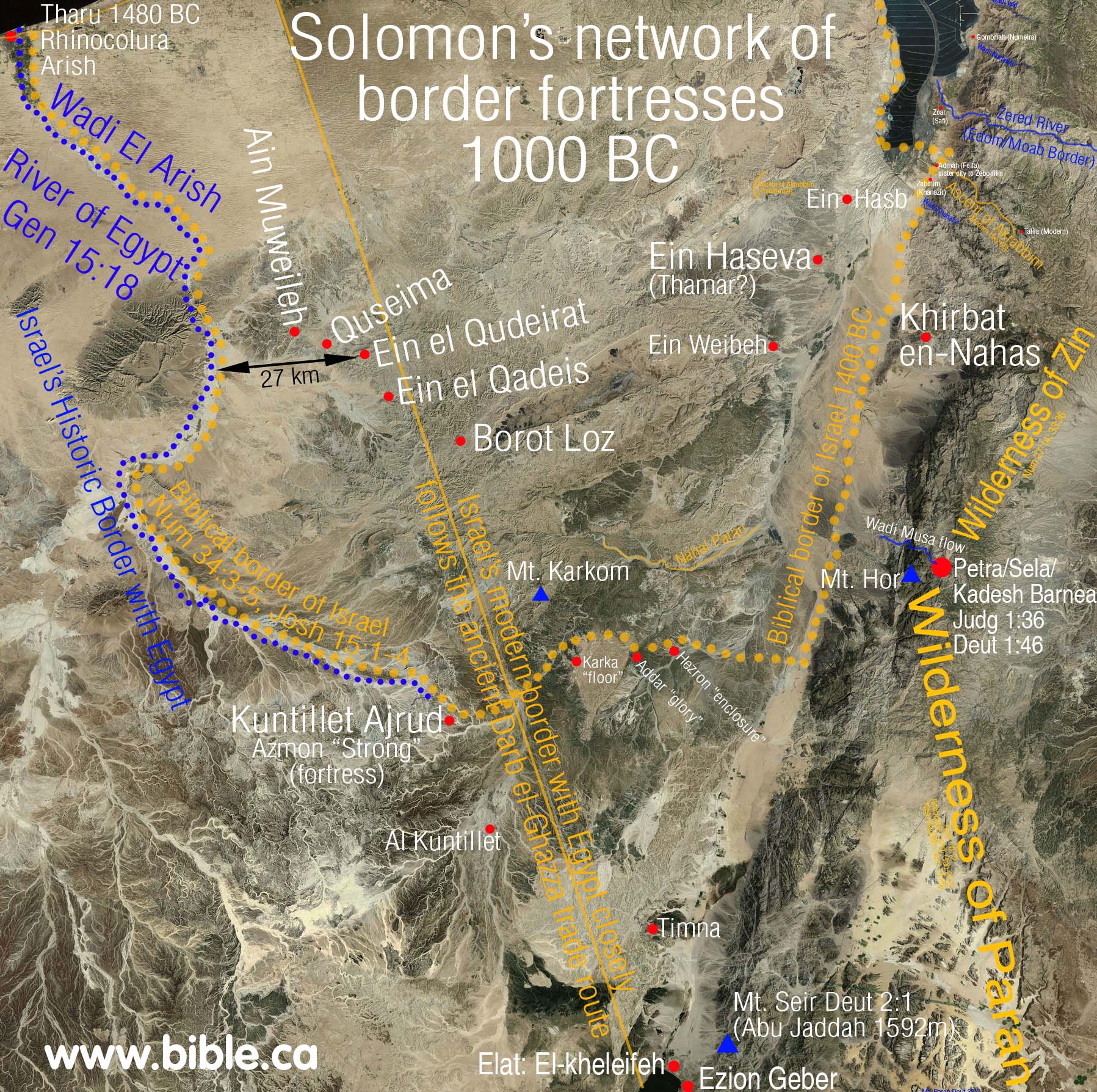

Introduction document: Solomon's network of military border fortresses |

|||

|

|

|||

Introduction:

- Ein El-Qudeirat means "Fountain of Omnipotence" or "Fountain of God s Power"

- If you want to take the easy short cut and skip all the reasons from the Bible, history and archeology why Qudeirat cannot be Kadesh, Click here to learn the true location of Kadesh Barnea now.

- For an detailed summary of the search for Kadesh Barnea see also: Chronological History of "The search for Kadesh"

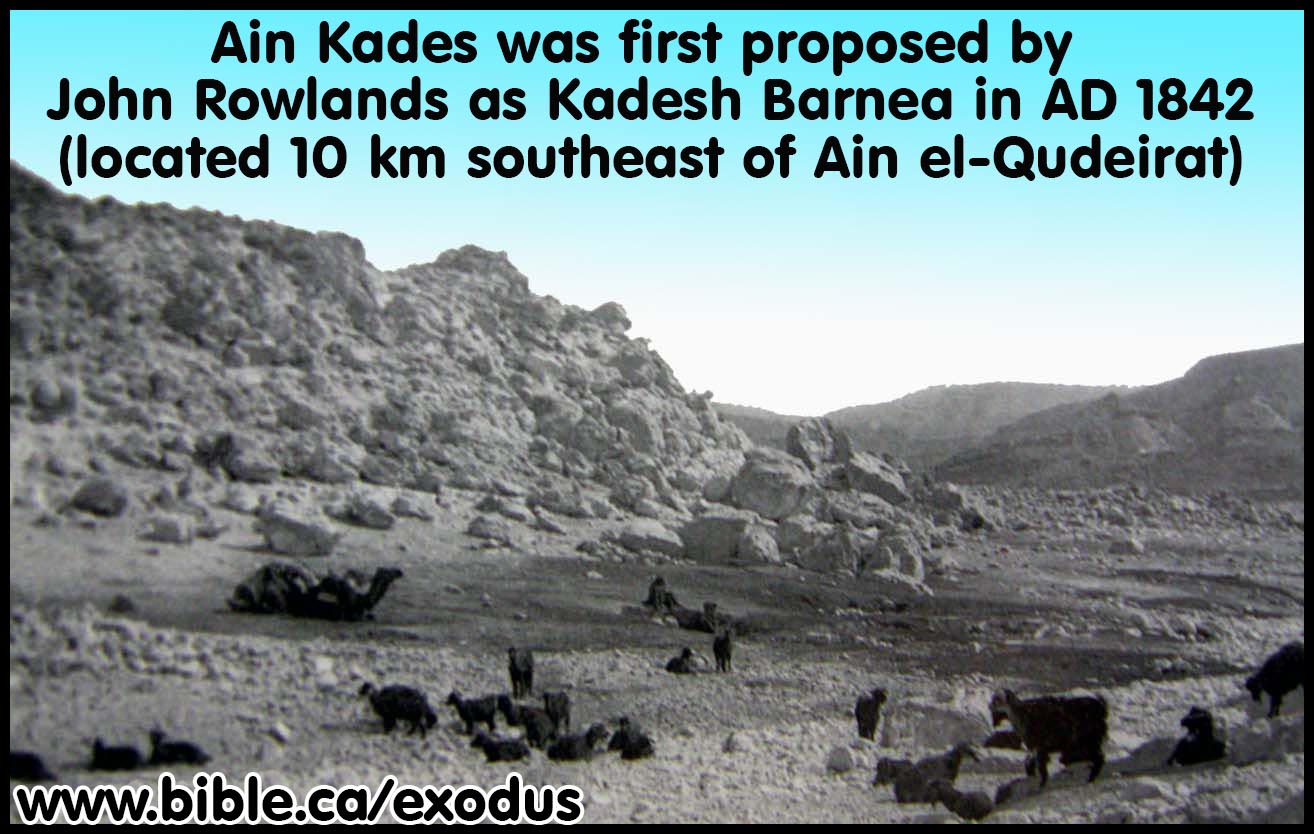

- John Rowlands goes down in history as the man who plunged the search for Kadesh Barnea in to the "Dark Ages" (1881 AD - present). But Ein Qedeis would be just another desert spring without Henry Clay Trumbull who is responsible for literally deceiving the entire world into believing it was Kadesh Barnea. The "one-two punch" of Rowland-Trumbull moved the worlds attention for the location of Kadesh from the Transjordan Arabah to where it has been presently located on all Bible maps since 1916 AD. Although in 1842 AD John Rowlands was the very first man in history to suggest Ein Qedeis was Kadesh Barnea, it became the majority opinion choice for Kadesh Barnea from 1881 - 1916 AD. Before 1881, everyone was looking for it in the Arabah Valley area or near Petra as Josephus said it was. After 1916, Qudeirat became the choice and is still to this very day. We however reject both Qedeis and Qudeirat as Kadesh Barnea and believe it is located at or near Petra. This "similarity of name" argument became the most important "proof" that Kadesh Barnea had been found at Ein Qedeis until Ein el-Qudeirat dethroned Ein Qeudeis in 1916 AD. Scholars like Keil & Delitzsch in 1867 AD, William Smith's Bible Dictionary in 1884 AD and the New Advent Catholic encyclopedia, Cades, 1917 AD all focused upon the similarity of name. But all this was thrown aside and forgotten when a larger spring was found 6 km north at Qudeirat. Ein El-Qudeirat means "Fountain of Omnipotence" or "Fountain of God s Power". This has nothing to do with any connection with God bringing water from the rock with Moses, but the fact that Qudeirat is the largest spring in the entire Sinai Peninsula for a 100 km radius! Not surprising that they would call it "God's powerful spring."

- God said in Ex 13:17-18 that He would lead them out of Egypt away from the very area that Qudeirat is located near. Why go to all the trouble of avoiding an area of the Philistines for 2 years at Mt. Sinai, only to have them camp on the Philistines doorstep for 38 years?

- Although

discovered years earlier, Ein El-Qudeirat was first identified as Kadesh

Barnea in 1916 AD. It has been the world's unfortunate choice for Kadesh

ever since even to the present time. Virtually all Bible maps incorrectly place

Kadesh at Qudeirat.

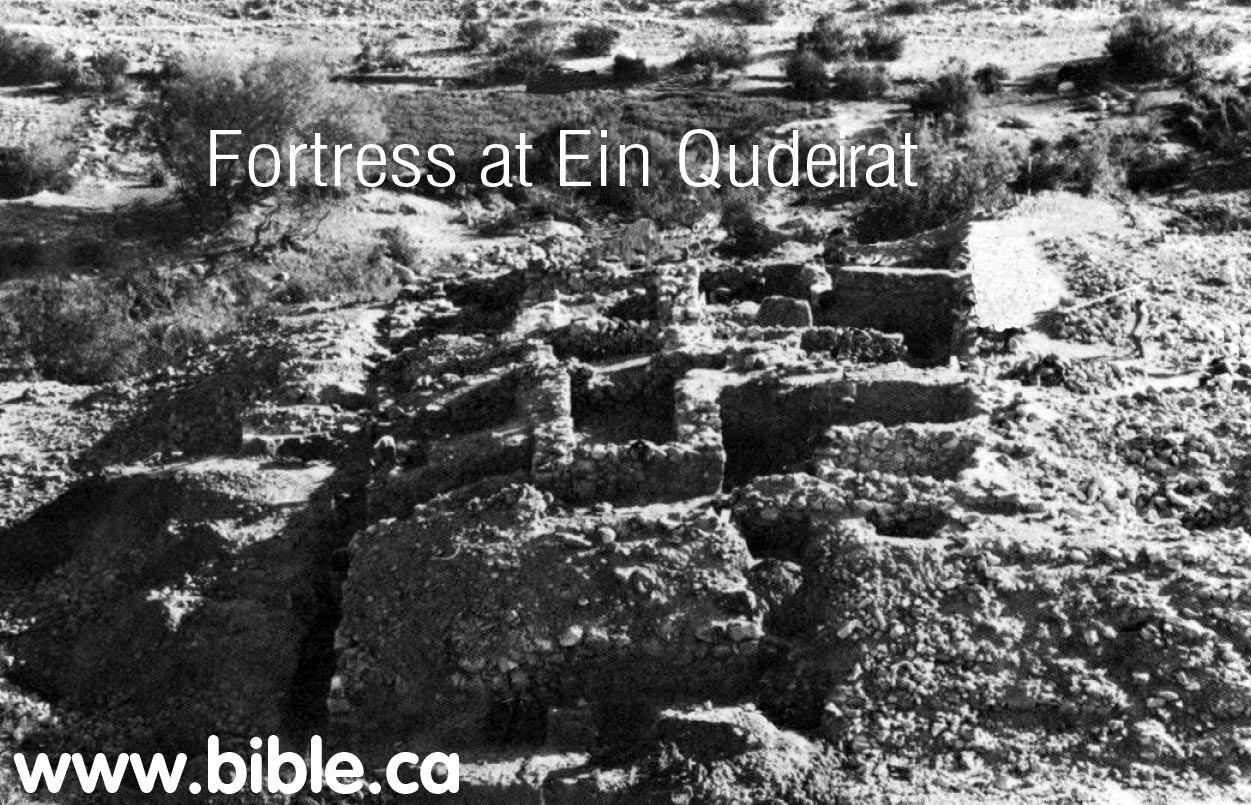

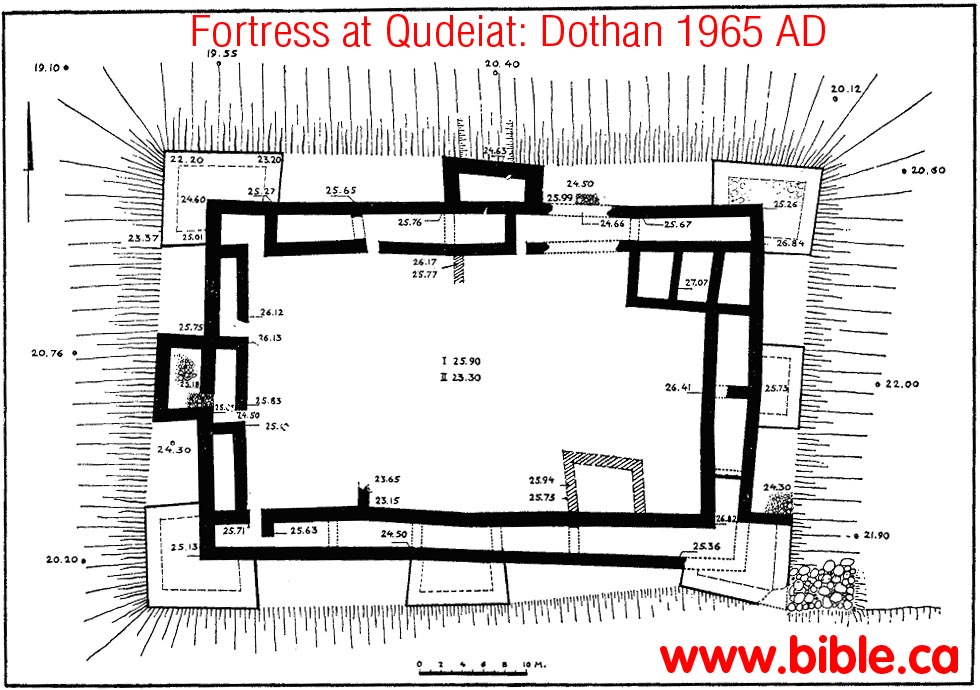

- "L. Woolley and T.E. Lawrence described the site and its eight-towered fortress and suggested that it be identified with biblical Kadesh-Barnea (The Wilderness of Zin, PEFA 3 [1914-1915], pp. 52-57, 69-71). The site was surveyed in 1934 by N. Glueck, in 1937 by R. de Vaux, and in 1956 by Y. Aharoni. In 1956, M. Dothan carried out excavations in the fortress of Kadesh-Barnea (1EJ 15 [19651, pp. 134-151)." (Kadesh-Barnea, 1976, Rudolph Cohen, Israel Exploration Journal, 1976 AD, p 201)

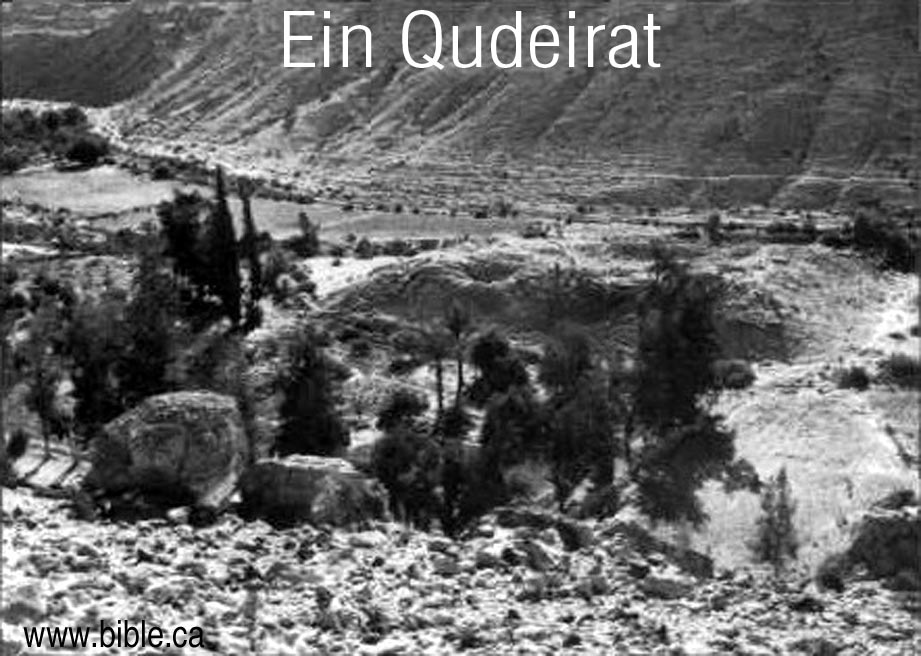

- Woolley and Lawrence (1914-15) suggested associating the relatively well-watered area of Tell el-Qudeirat in north-eastern Sinai with Biblical Kadesh Barnea, the main place of sojournment of the ancient Israelites in the desert following the Exodus from Egypt. Though many scholars have accepted the above suggestion, there is so far no independent evidence to confirm this viewpoint. (The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, Thomas E. Levy, Higham, Bruins, Plicht, 2005, p352)

- Qudeirat was the largest spring in the entire modern Sinai Peninsula: Dothan writes:

- "The tell is located near `Ein el Qudeirat, in Wadi el Ein, the richest spring in Sinai, which has a flow of about 40 cu. m per hour. This spring, which today is channeled into an irrigation network, and extends over some 2 km (Pl. 25, A), forms the largest oasis of northern Sinai. (The Fortress at Kadesh-Barnea, M Dothan, 1965)

- Gunneweg also says the same: "The Iron Age II fortress of Qadesh Barnea (nowadays called Tell 'Ein el-Qudeirat) is located in Wadi el 'Ein, a well ('Ein) which has fed the largest oasis of the southern Negev as well as northern Sinai from early times until the present (Dothan 1965, 134; Woolley and Lawrence 1914. 69-71; Cohen 1983, 93-4)". (Edomite, Negev, Midianite Pottery: Neutron Activation Analysis, Gunneweg, 1991 AD)

- "In fact, Ein-Qedeis is a shallow pool of water surrounded by a desert wasteland. Ein-Qedeis could not have been a major ancient center like Kadesh-Barnea. ... Its strategic location on two important ancient routes, its abundance of water and its correspondence with Biblical geography makes this the most likely candidate; no other site offers a convincing alternative. ... The springs of Ein el-Qudeirat are the richest and most abundant in the Sinai; they water the largest oasis in northern Sinai. (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- "Has

the site been correctly identified? If so, why have we found no remains

from the Exodus period? ... Thus far our excavations have yielded nothing

earlier than the tenth century B.C.—the time of King Solomon. (Did

I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem,

Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

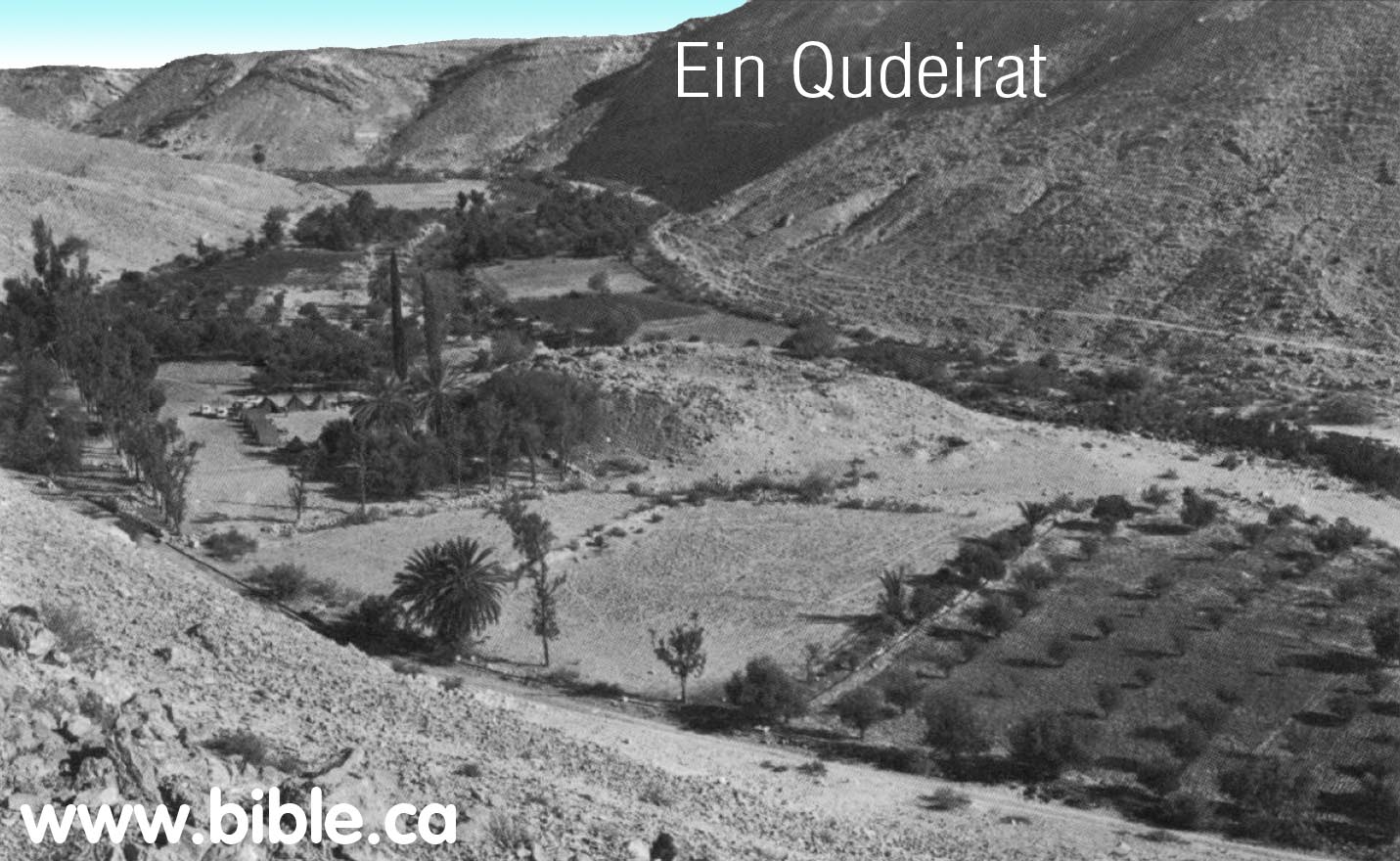

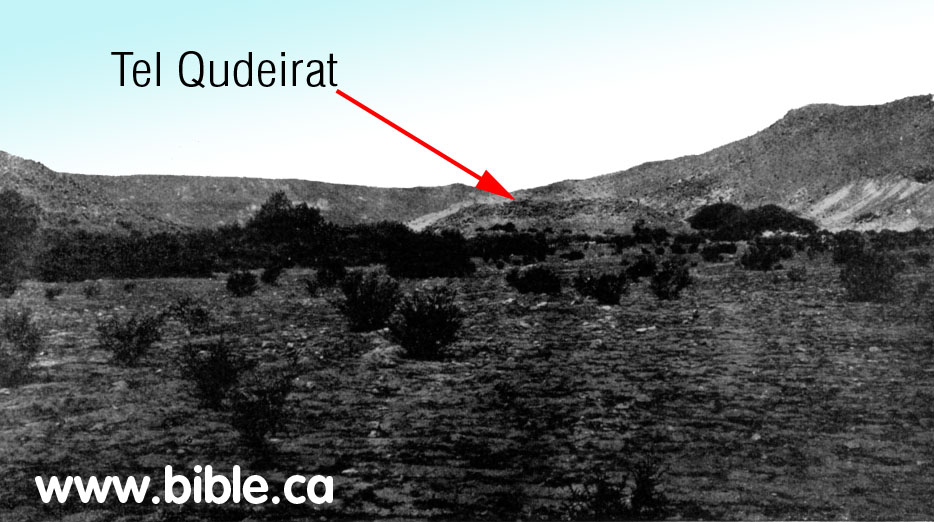

- Ein

El-Qudeirat is located in Wadi el Ein, a narrow dry valley that is a few

kilometers long.

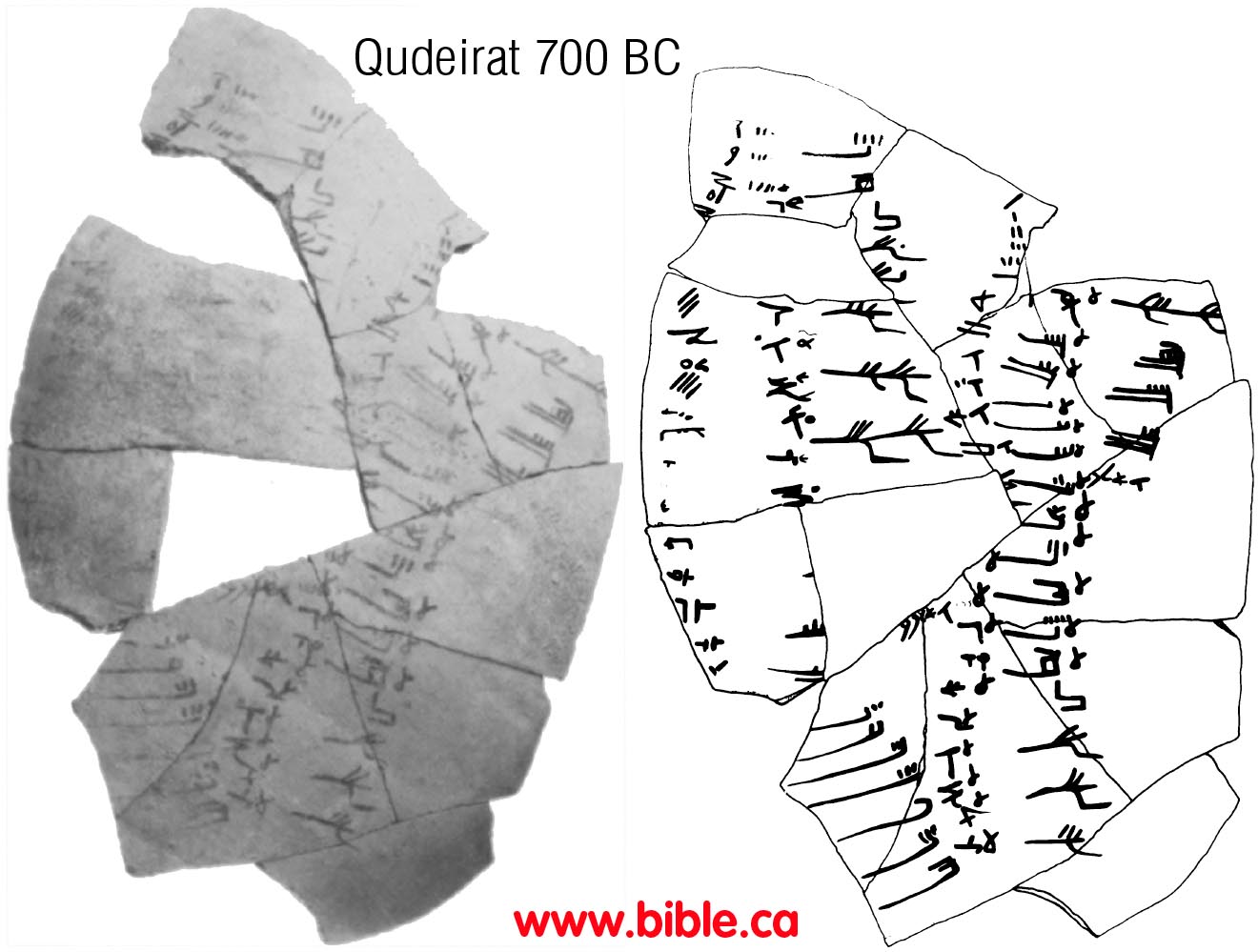

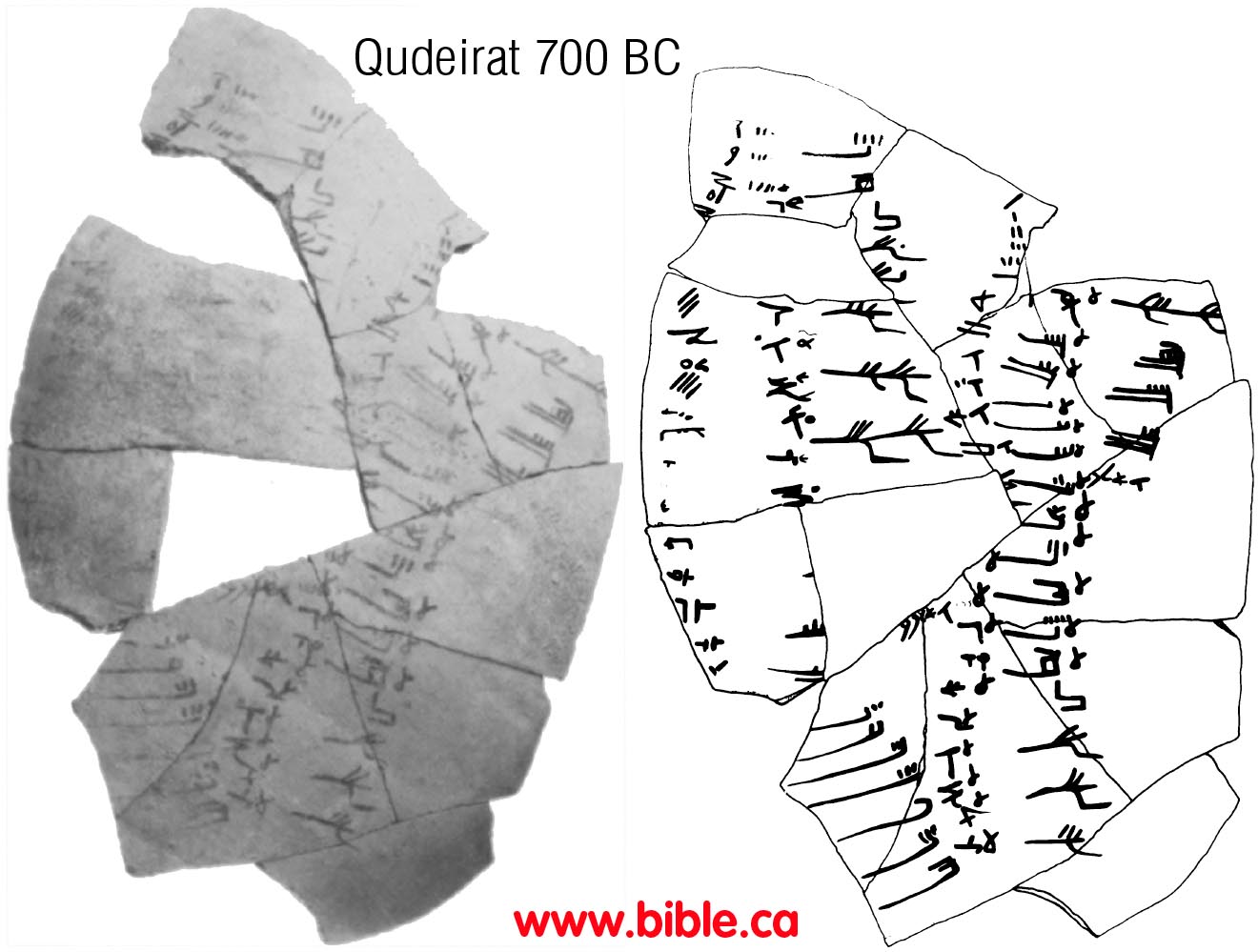

- Four

ostracons were found at Qudeirat. This one was found in the youngest

(highest) level about 700 BC. It is a conversion chart between Hebrew and

Egyptian numbering systems.

A. Top 10 reasons why Ein El-Qudeirat cannot be Kadesh Barnea:

- Ein El-Qudeirat cannot be Kadesh Barnea because it directly contradicts the Bible. Qudeirat is located 27 km inside the promised land. The wadi Al-Arish, or River of Egypt, was the formal stated boundary between Egypt and Israel (Gen 15:18). It is also the western boundary of the land of Judah. (Num 34:5; Josh 15:4,47; 13:5; 1 Ki 8:65) It is absurd to suggest that the children of Israel spent 38 years "wandering in the wilderness" well inside the promised land. This reason alone is all that is needed for anyone who believes the Bible to reject Ein El-Qudeirat as Kadesh Barnea. It is important to remember that the modern border of Israel since 1948 AD is at least 35 km east of where the border was in 1406 BC. Many people miss the fact that Qudeirat is actually located in the promised land because they are looking at modern maps.

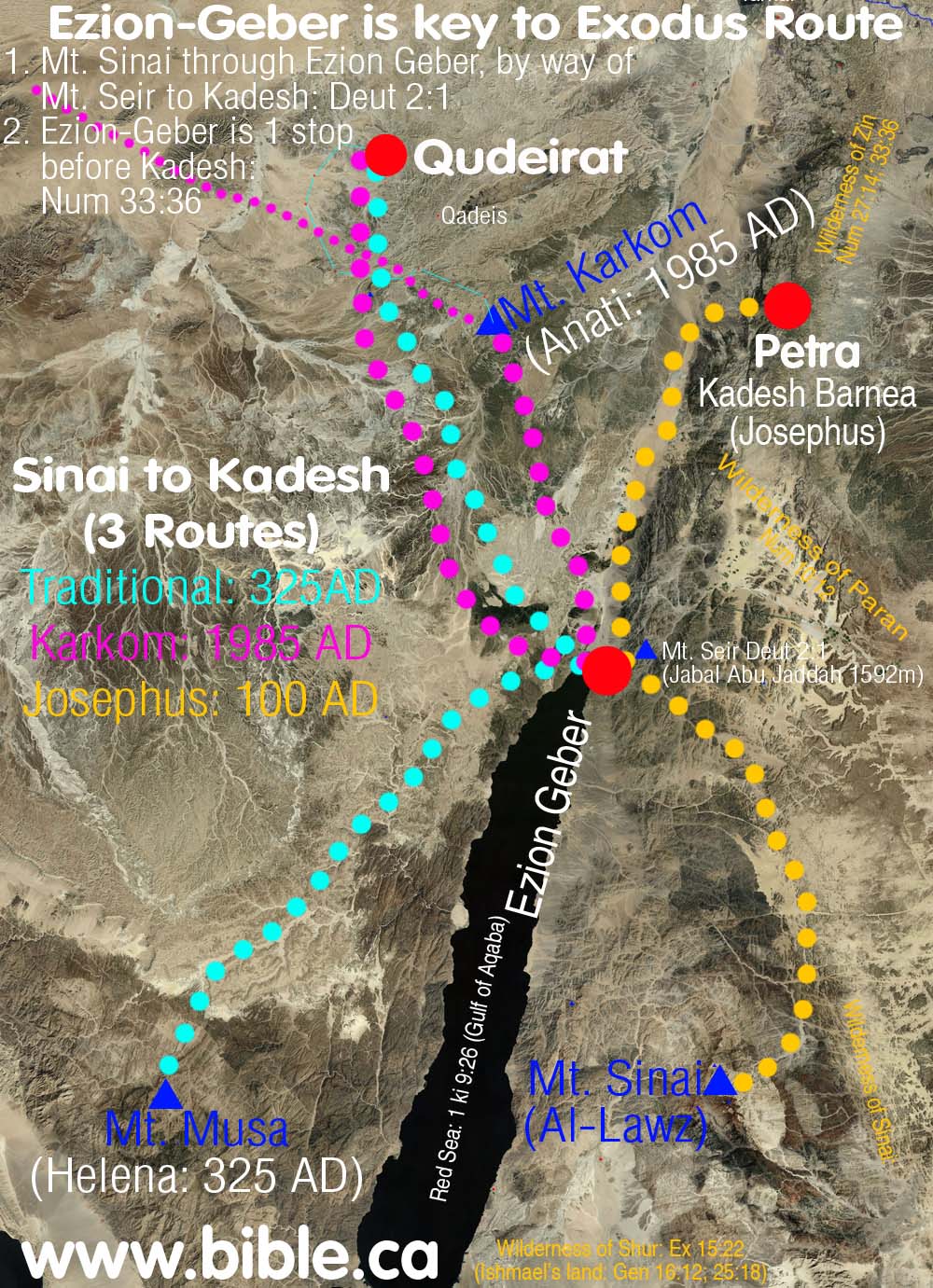

- Ezion-Geber

is a major Achilles heel to Ein El-Qudeirat being Kadesh Barnea. The

exodus route from Mt. Sinai to Kadesh went directly through Ezion-Geber.

While we may not be sure of where Kadesh was located, we can be absolutely

certain about the location of Ezion-Geber. It was located near modern

Elat, on the north shore of the Gulf of Aqaba. Almost every exodus route

map in the back of every Bible today has the route correctly passing

through Ezion-Geber, but for those who are familiar with the geography of

the area, they know that there is an enormous mountain range between the

Sinai desert and Ezion-Geber. If Mt. Musa is Mt Sinai (the traditional

location for Mt. Sinai at St. Catherine's Monastery, since 325 AD) and Ein

El-Qudeirat is Kadesh, this means that Israel had to twice cross this huge

mountain range: Once to get from the flatlands of the Sinai desert to the

Red Sea. Then cross the mountains a second time (basically back tracking)

onto the Sinai flatlands north to Qudeirat. Such a trip is even more

absurd in light of the fact that Ezion-Geber is only one stop away from

Kadesh Barnea (Num 33:36) and located inside Edomite territory. (1 Ki

9:26; 2 Chron 8:17)

- Josephus,

(50-110 AD) and Eusebius

(325 AD) says Mt. Hor (Aaron's burial place) was located at or near Petra.

Josephus' opinion would represent the basic views of the Jewish world at

the time of Christ. He is the oldest reliable historian who actually tells

us where Mt. Hor is located. Eusebius goes even further and says that

Kadesh Barnea is located at Petra. Eusebius represents the views of the

time of queen Helena, who chose the site for Mt. Sinai at St. Catherine's

Monastery in a vision. (Of course she was wrong about Mt. Sinai.) What is also

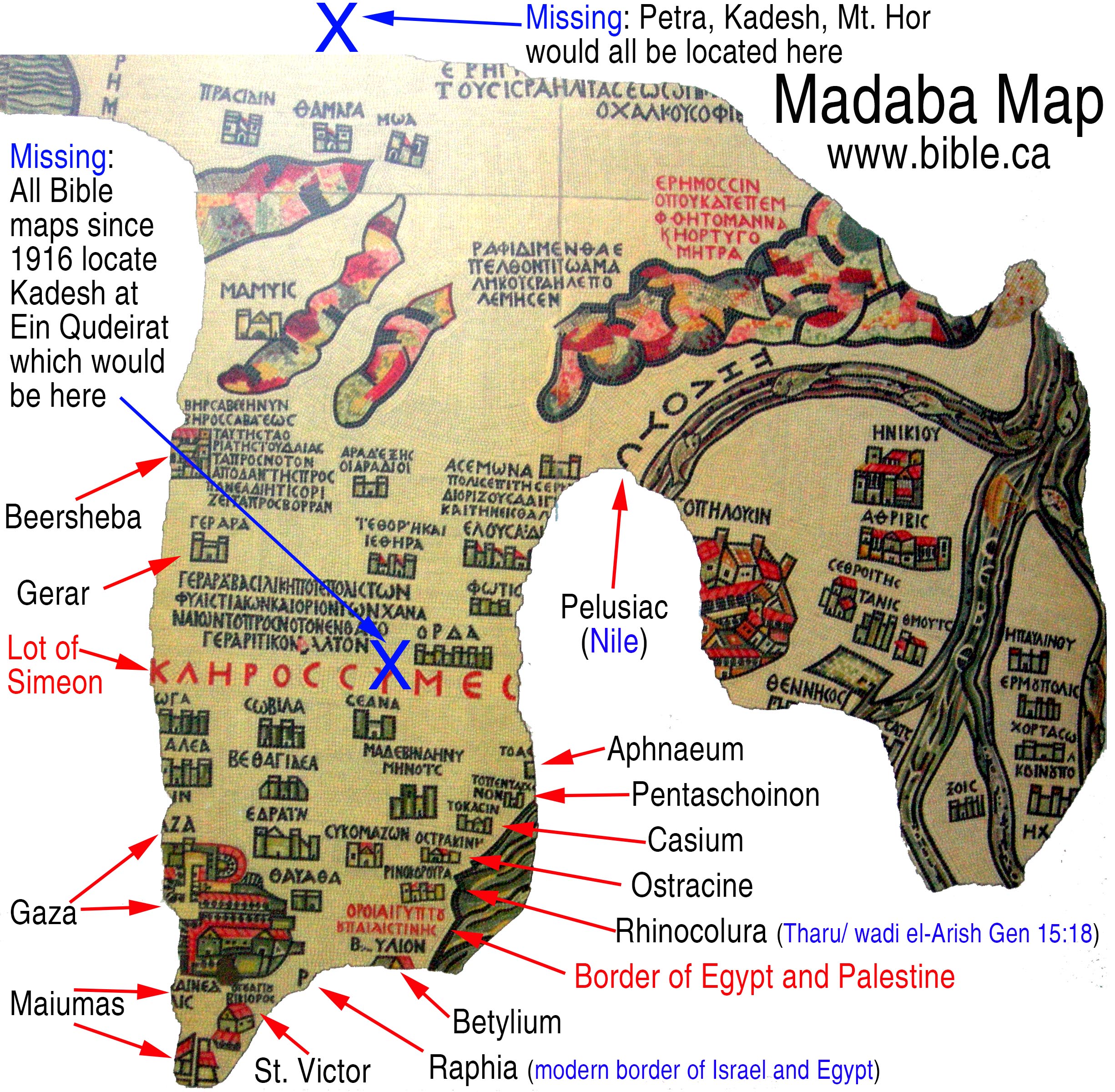

striking is that although Petra would have certainly been marked on the Madaba map in a section

defaced by the Muslims in 700 AD, Ein Qudeirat is missing from a section

of the map that remains. In other words, if Kadesh was located at

Qudeirat, it would have been in the section we can see today that the

Muslims did not destroy. Qudeirat should be located close to the large red

text, "lot of Simeon". Kadesh Barnea, if located at Qudeirat,

as most today wrongly believe, should be located on the map in a section that is not damaged. It is not located there; its

no where on the preserved map.”

- Qudeirat is the largest oasis in the Sinai Peninsula. Add the nearby oasis' at Quseima , Muweilih and Qedeis to Qudeirat and it simply does not fit the general description of Kadesh being a place where Israel bitterly complained about having no water. This is the place where Moses had to strike the rock to bring water for Israel. More details on Moses striking the rock at Kadesh.

- If it wasn't for the deceptions of Henry Clay Trumbull in 1884 AD, everyone would have continued to look for Kadesh transjordan, at or near Petra or in the Arabah valley. Trumbull's lies about the "New England look" of Qedeis, tricked the world into thinking it was Kadesh. 15 years later, when the next person arrived at Qedeis, it was rejected as Kadesh and Ein El-Qudeirat became the new location for Kadesh. Qudeirat is only 6 km north of Qedeis.

- Archeologists have found nothing in the entire Quseima area which includes Qedeis and Qudeirat, that is older than the time of Solomon (950 BC). Archeologically, we do find a series of military border fortresses built by Solomon at each of these locations, but this is 450 years too late to be connected with the exodus of 1446 BC.

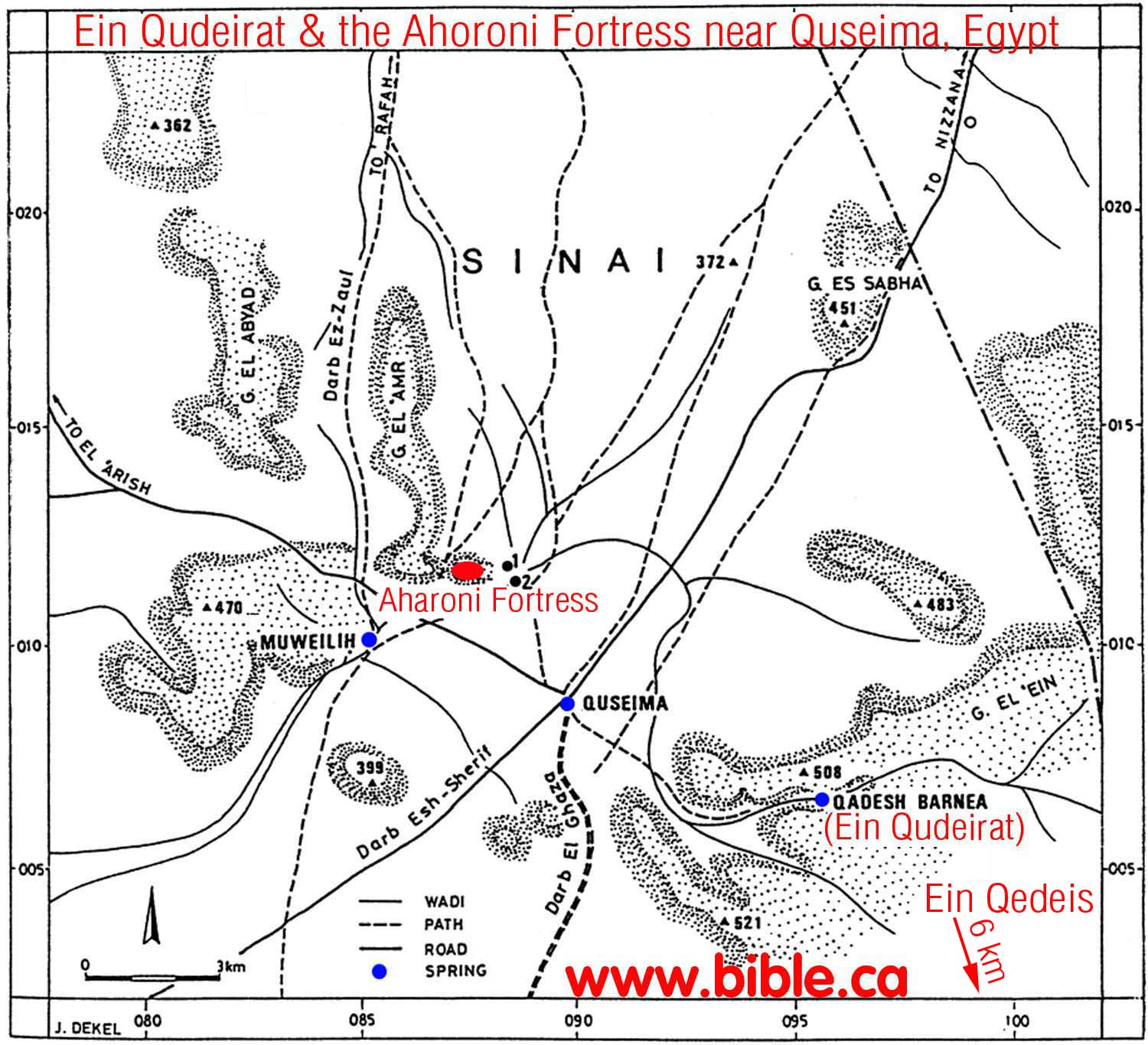

- Ein El-Qudeirat is located at the most important and central crossroads of the Sinai. There are four different crossroads that all converge in the Quseima area: Darb Esh-Sherif, Darb El Ghazza, Darb Ez Aaul, Darb El Arish. Since God was molding the culture and religion of the Hebrews during their 40 years in the wilderness, it makes no sense for God to have Israel spend 38 years in one of the most multi-cultural places in the middle east. God tucked Israel off in an isolated corner so he could cultivate his nation to worship him. Attempting to do this at the ancient equivalent of "Time Square" is significantly unlikely.

- 2.5 million people died at Kadesh. There are no mass grave sites located anywhere near Ein El-Qudeirat.

- Ein El-Qudeirat is located at least 100 km away from the land of Edom. Kadesh Barnea was located near the border of Edom. While many modern maps show the territory of Edom beside the Quseima area, this is not supported by archeology, but circular logic. They reason that Edom's border was located beside Kadesh, and since they falsely assume Kadesh is located at Ein El-Qudeirat, they just "pencil in" the land of Edom, nearby and randomly chose a new location for Mt. Seir and Mt. Hor where Aaron was buried! The problem is that both archeology and the Bible agree that Edom's territory was transjordan until after the Babylonian captivity of 605 BC when Nebuchadnezzar conquered all of Judah and took control of Jerusalem.

- It makes absolute non-sense of the story of asking Edom for permission to cross their territory to enter the promised land. They would just head straight north for Beersheba and not go the extreme long route across the Negev to the Arabah, then south to Ezion Geber, then east, then north to Mt. Nebo where Moses died. Of course, the Edomites did not even begin to inhabit any part of Judah until after Nebuchadnezzar first invaded in 605 BC.

|

Chronological History of the search for Kadesh 2000 BC - 2009 AD |

B. Qudeirat is strategically located at major "Quseima area" crossroads:

|

|

|||

|

The four springs of the Quseima area: |

|||

|

Map of the Quseima area showing the location of Ein Muweileh. |

|||

|

|

|||

- The largest oasis area in the modern Sinai will produce many major roads from all directions. Quseima was the "Time Square" or "Grand Central Station" of the Sinai.

- Quseima is the center of a four major ancient crossroads (Darb Esh-Sherif, Darb El Ghazza, Darb Ez Aaul, Darb El Arish)

- Not only was Qudeirat the largest single oasis in the Sinai, it was one of four springs in close proximity to each other. The four springs of the Quseima district are listed here from largest to smallest: Qudeirat, Qedeis, Quseima and Ein Muweileh.

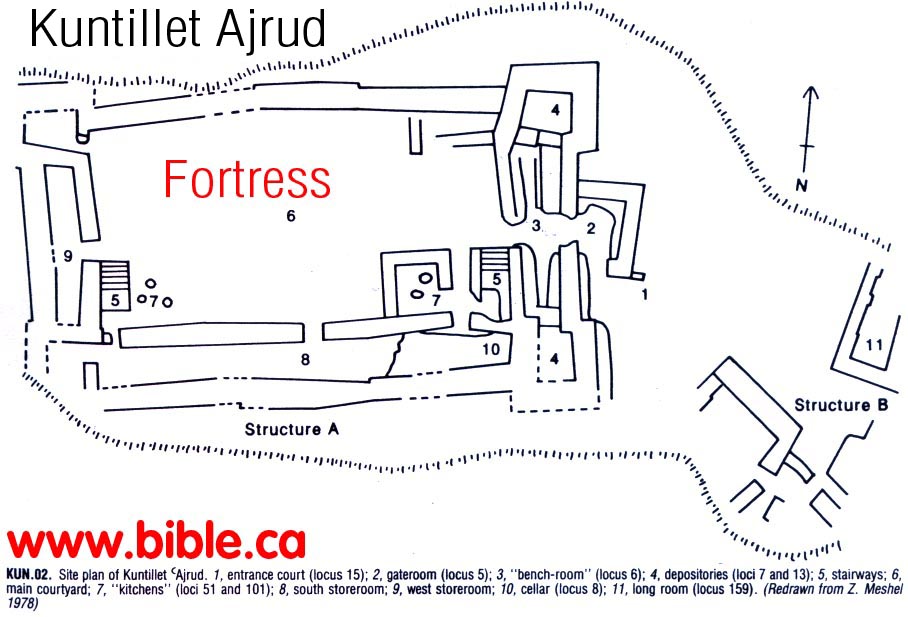

- Solomon built three border fortresses in close proximity to four of the springs: Forts were located at Quseima (which had two springs nearby) and Qudeirat and Qedeis. From a strategic point of view, the Quseima fortress was the most important because it was the most westerly and therefore closest to the Egyptian border and it overlooked the crossroads. The border between Egypt and Israel as stated in the Bible, is the wadi el-Arish.

- Meshel comments on the fortress at Quseima: "The summit, 390 m above sea level, rises some 140 m above the surrounding plain, permitting excellent observation in three directions. Among the more prominent points visible from the summit are the tip of the Qadesh Barnea oasis and the little oasis of Quseima, as well as Ein Muweilih. If there is any connection between the fortress and the routes formerly running through the plain, the fortress was clearly an excellent lookout point." ("Aharoni Fortress" near Quseima, Zeev Meshel, 1994 AD)

- Dothan comments on the network of roads that all converge in the Quseima area: "Nearby, there is an ancient crossroad: one road runs from Suez to Beersheba and Hebron, via Bir Hasana, Quseima and Nisanah (evidently Derekh Shur -or, ii-r); the other is a branch of the via maris originating from el-`Arish or Rafiah and continuing through Quseima and Kuntilla down to the Gulf of 'Aqaba. At the oasis and in the neighbouring region there are scattered remains of many temporary and permanent settlements, dating from the Palaeolithic, the Middle Bronze I and the Israelite, the Persian and the Roman-Byzantine periods. The large permanent settlement situated near the spring is Tell el-Qudeirat, which lies on the main road leading through the oasis." (The Fortress at Kadesh-Barnea, M Dothan, 1965)

C. Chronological History of Qudeirat as Kadesh

|

1916 -2004 AD: Ein el Qudeirat |

- NOTE: For a complete summary of the search for Kadesh Barnea see: Chronological History of "The search for Kadesh". The section below only deals with Qudeirat, the period of 1916 AD - present.

- In 1882, after Henry Clay Trumbull's one hour visit to Qedeis and choosing it as Kadesh Barnea, he traveled 6 km north to visit Ein El-Qudeirat. Like his deceptive account of the greenery at Qedeis, his account at Ein El-Qudeirat were also full of lies. He talked about dense vegetation and a 60 foot wide river and a 14 foot waterfall at Ein El-Qudeirat. Today, most of the vegetation is the result of modern irrigation techniques and it still isn't as "lush" as Trumbull described it. AYN EL-QADAYRAT DISCOVERED: The signs of fertility in this spur were far greater than in the main wady. Grass and shrubs and trees were in luxuriance, and the luxuriance increased at every step as we pushed on. One tree, called by our Arabs a " seyal " (or acacia), but not showing thorns like the acacias of the lower desert, exceeded in size any tree of the sort we had ever seen. Its trunk was double ; one stock being some six feet in girth ; the other, four feet and a-half. The entire sweep of the branches was a circumference of nearly two hundred and fifty feet, according to our pacing of it. "With such trees as that in the desert, it were easy enough to get the seyal, or shittim. wood, of suitable size for the boards and bars of the tabernacle. Still the luxuriance of vegetation increased. Then, as we proceeded, came the sound of flowing, and of foiling water. A water channel of fifteen to twenty yards in width, its stream bordered with reeds or flags, showed itself at our feet between the hills. We moved eastward along its southern border. Above the gurgling sound of the running stream, there grew more distinct the rush of a torrent-fall. As we pressed toward its source, the banks of the stream narrowed and rose, and we clambered them, and found our way through dense shrubbery until we reached the bank of the fountain-basin. There we looked down into a pool some twelve to fourteen feet below us; into which a copious stream rushed from out the hillside at the east, with a fall of seven or eight feet. The hillside from which this stream poured was verdure-covered, and the stream seemed to start out from it, at five or six feet below our level. The dense vegetation prevented our seeing whether the stream sprang directly out of an opening in the hillside, or came down along a concealed channel from springs yet farther eastward; but the appearance was of the former. Waving flags, four or five feet high, bordered this pool, as they bordered the channel below it. Our dragoman enthusiastically compared the fountain to that of Banias, away northward, at the source of the Jordan. It was certainly a wonderful fountain for the desert s border. Its name Ayn el-Qadayrat the " Fountain of Omnipotence," or " Fountain of God s Power," was not inappropriate, in view of its impressiveness, bursting forth there so unexpectedly, as at the word of Him who " turneth the wilderness into a standing water, and dry ground into water springs." No wonder that this fountain was a landmark in the boundary line of the possession, which had been promised of God to his people, as " a land of brooks of water, of fountains and depths that spring out of valleys and hills." Viewed merely as a desert-fountain, Ayn el-Qadayrat was even more remarkable than Ayn Qadees ; although the hill-encircled wady watered by the latter, was far more extensive than Wady Ayn el-Qadayrat; and was suited to be a place of protected and permanent encampment, as the latter could not be. Perhaps it ought to be mentioned, that the "date-palms " which Scetzen spoke of as watered by this fountain, were not seen by us. Yet they may have been elsewhere; or indeed, they may have existed in his day, although not now remaining. There was a peculiar satisfaction in looking at this remarkable fountain, when at last we had reached it. No visit to it had been recorded by any traveler in modern times. Seetzcul and Robinson, and Rowlands, and Bonar and Palmer, and others, had been told of it, and had reported it accordingly; but no one of them claimed to have seen it. In view of all that these travelers had said, and after his own careful search for it, up and down the wady, Bartlett, (as has already been mentioned) had come to the conclusion that no such fountain existed that, in fact, Wady el-Ayn, the Wady of the Well, was a wady without a well. To put our eyes on it, therefore, the very day of our seeing Ayn Qadees, was enough to drive out of mind all thought of our dangers and worry on the way to it. We congratulated one another all around; and Muhammad Ahmad was promised anew that he should go into that book" Silk Bazar," and all." (Kadesh-Barnea Henry Clay Trumbull, 1884 AD)

- In 1905 Nathaniel Schmidt visited Qudeirat and rejected it as Kadesh and chose Petra instead. In 1981 AD, Rudolph Cohen misrepresented Nathaniel Schmidt as the first one to identify that Ein el-Qudeirat was Kadesh. In fact Schmidt considered Weibeh, Kades and Qudeirat, rejected them all and concluded that Kadesh was at Petra: "It seems to me even more probable that Petra was the original scene of these stories." (Kadesh Barnea, Nathan Schmidt, Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol 29, no 1, 1910 AD, p75-76) Cohen says: "In 1905, Nathaniel Schmidt first identified Kadesh-Barnea as the modern site of Ein el-Qudeirat. Schmidt marshalled his arguments: "The sheltered position, the broad stream of water... Its strategic location on two important ancient routes, its abundance of water and its correspondence with Biblical geography makes this the most likely candidate; no other site offers a convincing alternative. ... The springs of Ein el-Qudeirat are the richest and most abundant in the Sinai; they water the largest oasis in northern Sinai." (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- In 1914, Woolley and Lawrence compared the two sites of Qedeis and Qudeirat and decided that Kadesh Barnea was somewhere in the Quseima district, most likely at Qudeirat, since it was the largest of four springs: "Strategically the Kossaima district agrees well with what we know of Kadesh-Barnea. ... These roads running out to north, south, east and west - all directions in which journeys were planned or made from Kadesh-Barnea - together with its abundance of water and wide stretch of tolerable soil, distinguish the Kossaima plain from any other district in the Southern Desert, and may well mark it out as the headquarters of the Israelites during their forty years of discipline.(The Wilderness of Zin, C. Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, CH IV, Ain Kadeis And Kossaima, 1914-1915 AD)

- Woolley and Lawrence knew that they would have to abandon the traditional location of Mt. Hor beside Petra and chose a new location of the burial place of Aaron, basically at random: "To choose today out of the innumerable hills of the country one particular peak to be the scene of Aaron's burial shows, perhaps, an uncatholic mind; but as long as the tradition of Jebel Harun passes muster, so long the existence of recognized roadways between the mountain and the Kossaima plain must influence our judgment." (The Wilderness of Zin, C. Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, CH IV, Ain Kadeis And Kossaima, 1914-1915 AD)

- Woolley and Lawrence published their book in 1916 AD in which they chose Ein El-Qudeirat as Kadesh Barnea, and the entire world jumped on board with them.

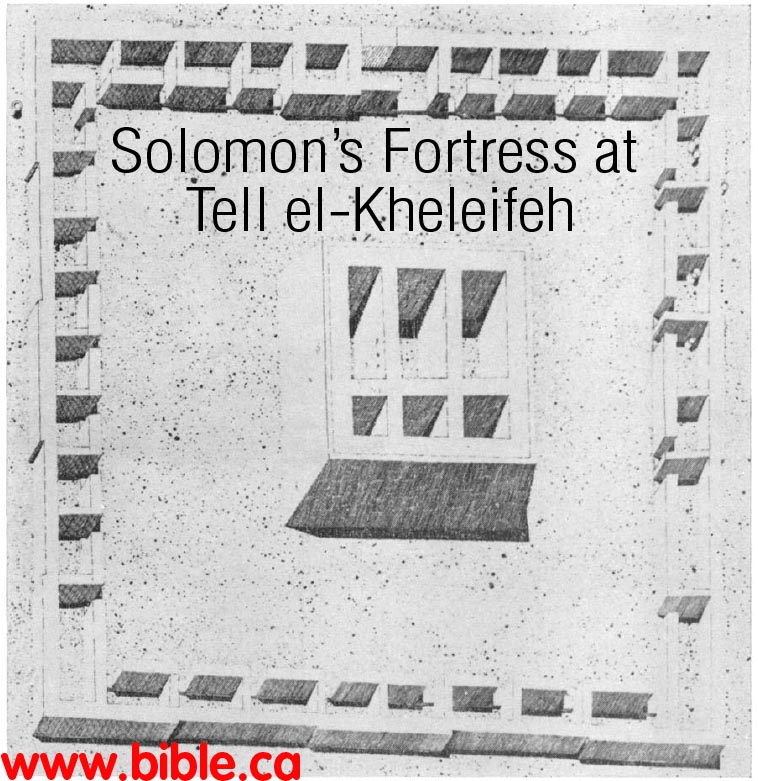

- Woolley and Lawrence really had only superficial information when they chose Qudeirat as Kadesh. They made many mistakes typical of the science of archeology of the time. For example, at Tell el-Kheleifeh (ancient Elat) "Glueck threw out most of the common wheel-made pottery he excavated; he did not realize this common wheel-made pottery was far more reliable for dating purposes than the handmade pottery he saved.)" (Jezirat Faraun: Is This Solomon's Seaport?, Alexander Flinder, 1989 AD) This was 25 years after Woolley and Lawrence excavated at Qudeirat. Who knows what errors they made?

- It is interesting that Woolley and Lawrence wrongly wondered if the fort at Qudeirat already existed when Moses arrived. Of course, this was in 1916 AD and now we know that the remains at Qudeirat were built some 400 years after Moses, by Solomon. Today, we know that Ein El-Qudeirat, is not even Kadesh Barnea, so Moses was never even here: "At a later date Moses, writing to the King of Edom, described Kadesh as `a city in the uttermost of thy border' (Numbers xx, 16). The word `city' is a vague one, and probably only means a settlement, perhaps a district, like the modern Arabic beled which is used to mean town, village, district, or country. In the former sense it might be used of such hut-settlements as those of Muweilleh and Kossaima; but would most temptingly apply to the fortress of Ain Guderat [Qudeirat], should we assume - we cannot prove it - that the fort was already built when Moses came." (The Wilderness of Zin, C. Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, CH IV, Ain Kadeis And Kossaima, 1914-1915 AD)

- Excavations at Qudeirat were carried out 1914-1915 AD by Woolley and Lawrence. They published their finds in the book The Wilderness of Zin. This book convinced the world that Qudeirat was in fact Kadesh and so it so to the present time.

- Shortly after 1916 AD, the world rejected Ein El Qedeis for Kadesh. The new location for Kadesh was about 10 km north at Ein el-Qudeirat after Woolley and Lawrence published their book. Qudeirat has been the almost undisputed location for Kadesh Barnea from 1916 to the present time. However Qudeirat simply cannot be Kadesh Barnea for a long list of reasons discussed elsewhere.

- Today Ein El-Qudeirat is still the location for Kadesh Barnea in almost every Bible map produced. This is a grave mistake since Kadesh Barnea is located transjordan, near or at Petra, right where Josephus and Eusebius in the Onomasticon said it was.

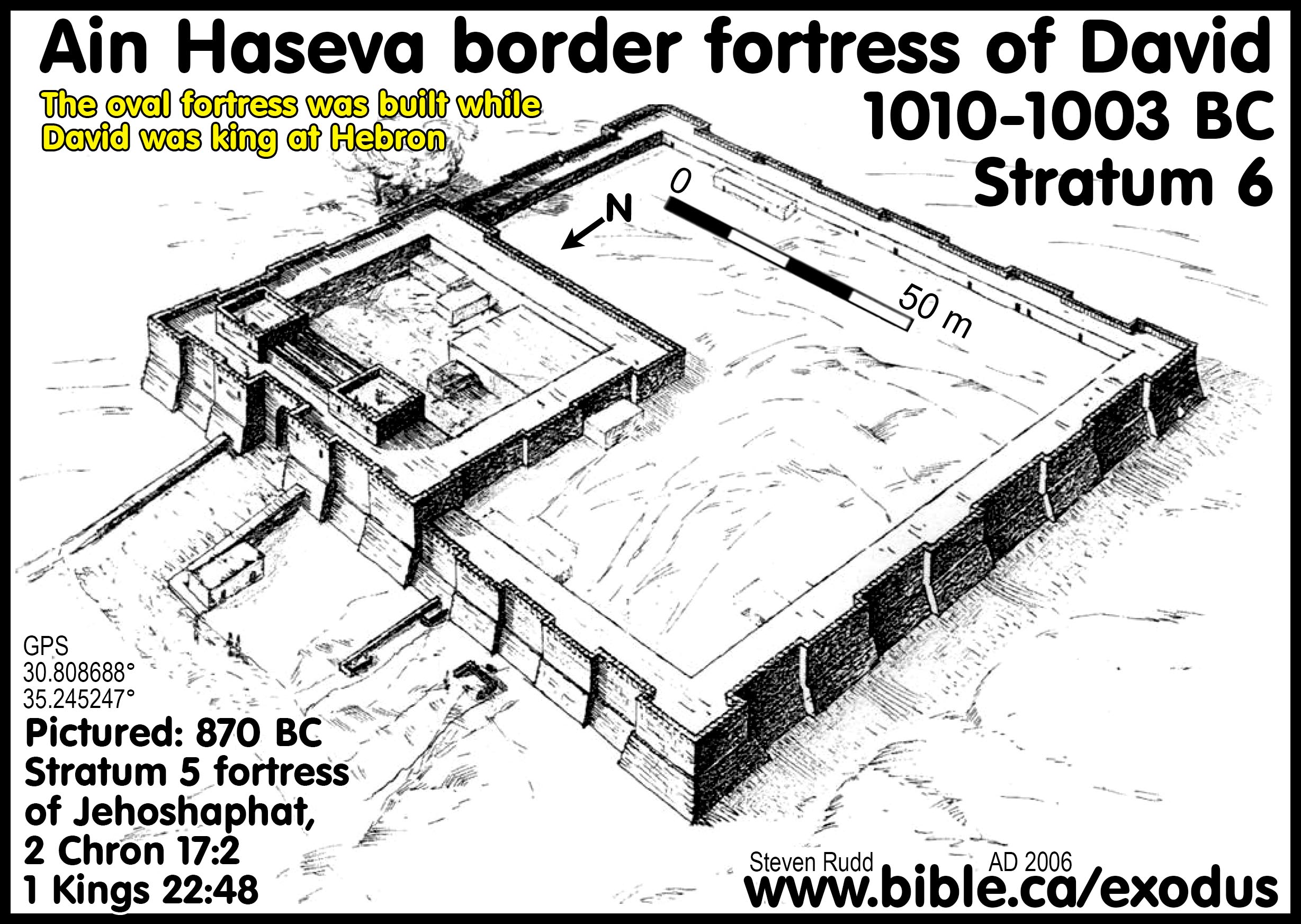

D. Qudeirat was part of a network of fortresses built by Solomon:

Map of the Quseima area:

- Ein El-Qudeirat, was the location of one of Solomon's fortresses he built to protect the border in 950 BC. For more details see: Solomon's network of military border fortresses.

- When Woolley and Lawrence first came upon the fortress in 1914, they imagined that the structure predated Moses: "should we assume - we cannot prove it - that the fort was already built when Moses came." (The Wilderness of Zin, Woolley and Lawrence, 1914-1915 AD)

- Next thing you know they proclaim the site to be Kadesh Barnea with the expectation that further detailed archeological evidence would prove such. Darwin had the same wishful thinking when he assumed future discoveries of fossilized animals would give direct evidence evolution between ape and man. Today anthropology has proven Darwin wrong and archeology has proven Woolley and Lawrence wrong. Although millions of fossilized animals have now been found not one is transitional as Darwin expected. Likewise, after extensive archeological investigation of Qudeirat, nothing earlier than the time of Solomon has been found. Darwin hoped for the missing link that is still missing. Woolley and Lawrence hoped for the missing "pottery" that would prove that Moses lived there for 38 years. Rudolph Cohen echoed the same hopes of Woolley and Lawrence, yet in 2008, we still have found nothing earlier than 950 BC at the site.

- We consider the late Rudolph Cohen to be the world's top authority on Qudeirat. He recognized the dilemma that the lack of archeological evidence posed to Qudeirat being the correct location for Kadesh Barnea: "Has the site been correctly identified? If so, why have we found no remains from the Exodus period? ... Thus far our excavations have yielded nothing earlier than the tenth century B.C. - the time of King Solomon." (Rudolph Cohen)

- The late Rudolph Cohen, like Darwin also expected further discoveries to vindicate the site as Kadesh. Although he noted that he had excavated down to virgin soil, he also noted that only a portion of the site had been excavated down to virgin soil. He indicated his hopes that future excavations (still have not been done today) would provide the evidence he lacked.

- Rudolph Cohen recognizes that all the man made structures at Qudeirat do not predate Solomon but were part of the border fortress network.

- "The

earliest of Kadesh-barnea's three successive fortresses is 10th century

B.C. in date and presumably belongs to the above-discussed fortress

network. However, while most of the other fortresses demolished in Pharaoh

Shishak's assault were permanently abandoned, the fortress at Kadesh-barnea

was twice rebuilt and reoccupied. In the 8th-7th centuries a solid-walled

fortress was erected on the site, and in the 7th-6th centuries B.C. a

towered fortress was introduced, paralleled only by another large

fortress, of similar type, at H. `Uza (above). Thus, of all the Iron Age

sites in the Central Negev, Kadesh-barnea alone was twice singled out for

reconstruction. This may, of course, be explained by its strategically

crucial location at the juncture of two main desert routes. Alternatively,

it is possible that the site was particularly sacred to the Israelites of

the Monarchy because of its association with Moses and the Exodus, and

that the fortress was therefore important for religious as well as

practical reasons. This, to be sure, is conjectural at present. In any

event, the final fortress at the site remained in use until the end of the

Iron Age and was evidently destroyed, along with the Kingdom of Judah, in

the Babylonian campaign (Malamat 1968, 1975)." (The

Iron Age Fortresses in the Central Negev, Rudolph Cohen, 1979 AD)

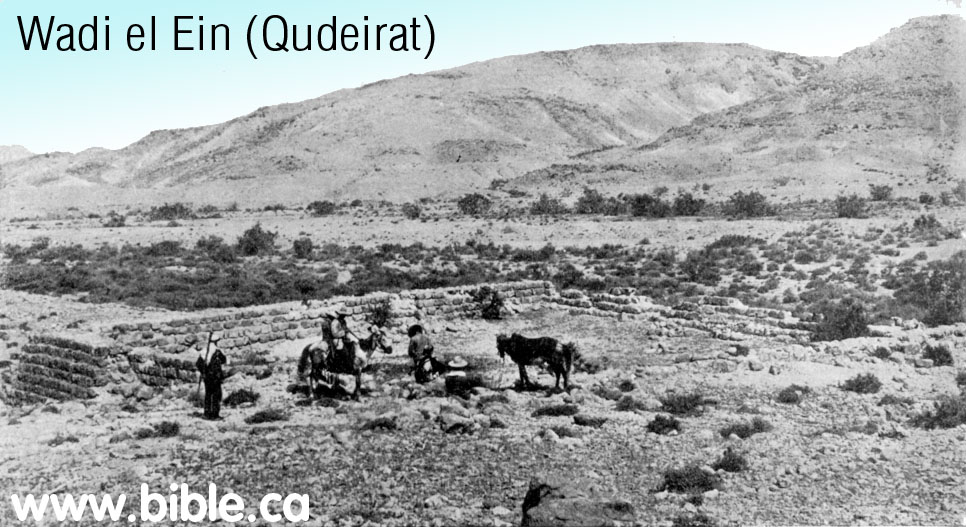

- Tel

Qudeirat in 1905 before any excavation: Schmidt:

- "The sites excavated by Cohen have all produced remains of the typical 10th-century "four-room house" associated with Israelite settlements throughout the country." (Kadesh Barnea: Judah's Last Outpost, Carol Meyers, 1976 AD)

- "The central Negev was settled only during the United Monarchy, when King Solomon followed a deliberate pattern of expansion and construction of forts." (Kadesh Barnea: Judah's Last Outpost, Carol Meyers, 1976 AD)

- "The earliest fortress at Kadesh-Barnea [Qudeirat] belonged to an extensive fortress network which ran across the Central Negev, extending south from present-day Dimona, past Yeruham and Sde Boker, to the edge of the erosion crater of Makhtesh Ramon, and then turning west toward the site of Kadesh-Barnea. Scores of such fortresses have been recorded since Woolley and Lawrence's pioneering survey in 1914. In my opinion, this network of fortresses was established by King Solomon to protect his trade routes and to secure his southern border. Most of these fortresses were occupied only briefly, and were apparently destroyed in the course of Pharaoh Shishak's invasion of Palestine in about 920 B.C. following King Solomon's death (1 Kings 14:25-26). After Pharaoh Shishak's attack, the Kingdom of Judah withdrew to its old boundary along the Beersheva basin, and the fortress network in the Central Negev was never rebuilt. At Kadesh-Barnea, however, a fortress was re-established in the eighth-seventh centuries B.C. over its predecessor's remains. (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

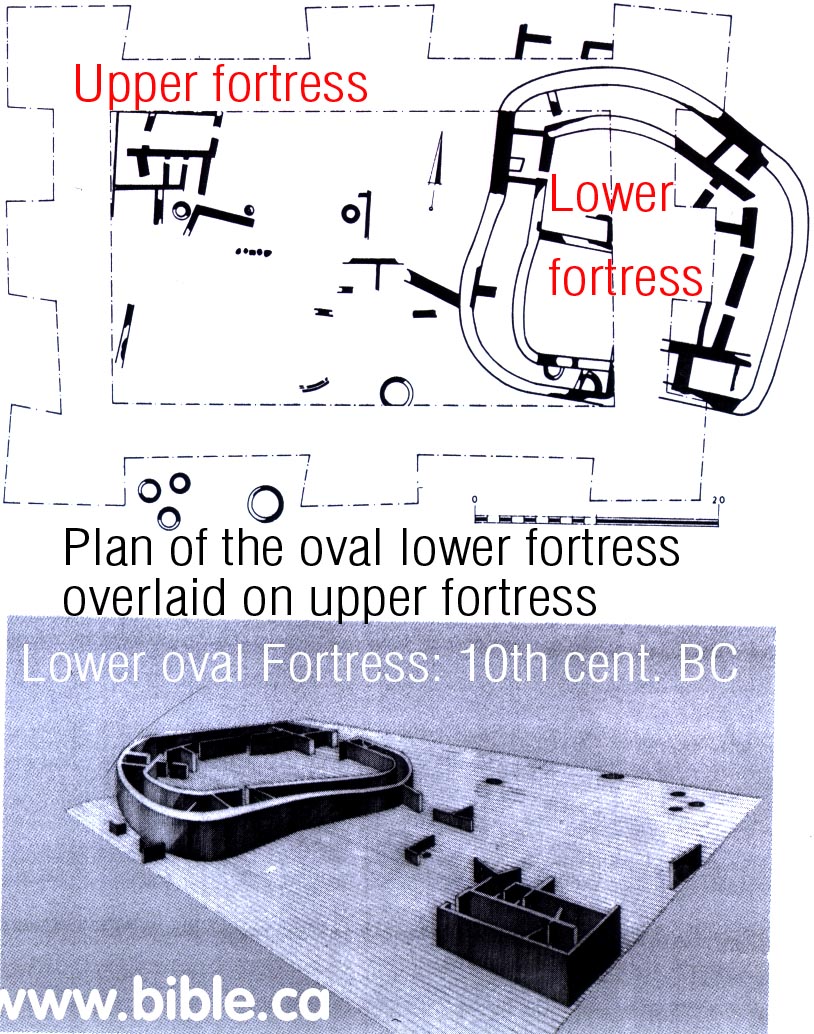

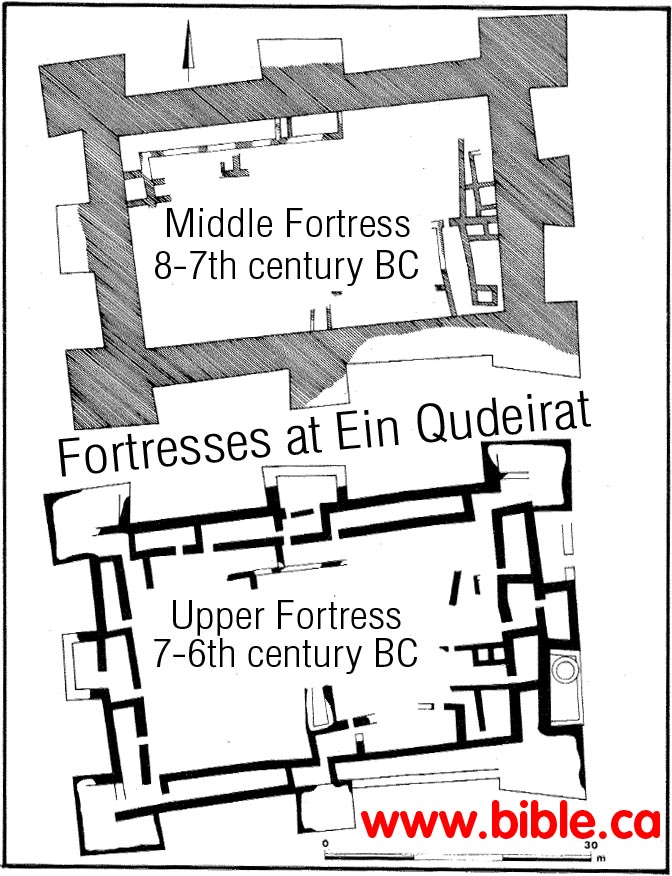

E. Ein el-Qudeirat had three fortresses: (built and destroyed three times)

- "Our archaeological excavations have revealed the ruins of three Iron Age (Israelite) fortresses on the tell, each, except for the first, built over its predecessor. These fortresses date from the tenth to the sixth centuries B.C. and provide important data which help flesh out the tangled history of this period. ... It is significant that, of all the Iron Age fortresses in the Central Negev and Sinai, only Kadesh-Barnea was twice rebuilt." (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- 950 BC Solomon:

"Oldest of three fortresses: 950 BC (bottom layer, last excavated

down to virgin soil): The remains of a third fortress, the earliest, were

found in the southeastern corner of the tell. ... We were able to date

this earliest fortress at Kadesh-Barnea by discovering on its floor in an

ash layer wheel-made and hand-made pottery characteristic of the

tenth-ninth centuries B.C. This fortress was

established on virgin soil; nothing earlier appears. (Did

I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem,

Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- 800 BC:

"Second of three fortresses: 800 BC (middle layer, second excavated):

Underneath this uppermost fortress were the remains of another, earlier

fortress. ... dated to the eighth-seventh centuries B.C. (Did

I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem,

Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- 700 BC:

"Youngest of three fortresses: 700 BC (top layer, first excavated):

The uppermost, and therefore latest, fortress at Kadesh-Barnea

...belonging to the seventh-sixth centuries B.C.(Did

I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem,

Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

"The final fortress remained in use until the end of the Iron Age and evidently was destroyed, along with the kingdom of Judah, in the course of Nebuchadnezzar's campaign. Afterward, as related above, there are merely some signs of Persian occupation in a limited number of areas on the tell." (Excavations At Kadesh-Barnea: 1976-1978, Ein el-Qudeirat, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- "The Qadesh Barnea fortress has three complexes corresponding to phases spanning about 300 years; they are called the upper, middle and lower fortress. `Edomite' pottery has only been found within the ashes from the conflagration of the upper fortress in the context of Cypro-Phoenician juglets, a collection of tens of handmade, coarse `Negbite' pots, and a predominance of Judahite vessels reminiscent of the seventh to sixth century BC (Cohen 1983, 100)." (Edomite, Negev, Midianite Pottery: Neutron Activation Analysis, Gunneweg, 1991 AD)

- "The excavations this season were focused on the northern, southern and eastern part of the mound and confirmed our previous conclusion that three fortresses had been erected on the site, each one built over its predecessor's remains." (Kadesh-Barnea, 1979, Rudolph Cohen, Israel Exploration Journal, 1980 AD, p 235-236)

- "Fortresses with Towers. Two examples of this type of fortress are known in the Central Negev: Kadesh-barnea and H. Uza. a. Kadesh-barnea. The fortress of Kadesh-barnea (Grid Reference 0949 X 0064) is located on Tell 'Ain, at the most important desert juncture in this region (fig. 9). It was first surveyed by Woolley and Lawrence in 1914, and their identification of the site with biblical Kadesh-barnea is generally accepted today. In 1956 excavations carried out by M. Dothan on behalf of the Department of Antiquities (1965: 134-51) illuminated numerous details of the fortress plan, fixing the date of its erection to the 9th-8th centuries B.C. and the date of its destruction to the 7th-6th centuries B.C. In 1976 and 1978 further excavations were carried out by the author (Cohen 1976a: 201-2; Meyers 1976). His findings indicate that the upper fortress was built during the reign of Josiah on the remains of two earlier fortresses, built likewise one over the other (fig. 10). The latest fortress is a rectangular structure (ca. 60 X 41 m.), consisting of casemate walls around a central courtyard (fig. 11b). It has eight projecting towers, also roughly rectangular, one in each corner and one in the middle of each of the four sides. The walls, ca. 1 m. in width and preserved to a height of ca. 1.20 m., are of rough-hewn local limestone blocks. In the past three seasons of excavations most of the casemate rooms have been exposed in all four sides of the fortress. Their sizes vary considerably: width, from ca. 2-3 m.; length, from ca. 5-10 m. The towers also vary in size, but those in the corners are consistently larger than those in the middle of the walls. The northeastern tower, for example, which was exposed in the excavations, projects ca. 4.50 m. from both the northern and eastern casemate walls, but, being set somewhat further to the west, its northern side is ca. 10 m., while its eastern side is only ca. 8 m. By contrast, the tower in the middle of the fortress' eastern wall projects ca. 3.50 m. from the casemate line and is ca. 7.50 m. long. Additional rooms were built in the courtyard against the southern casemate wall. The location of the gate has not yet been determined. The beaten-earth floors of the casemate rooms were covered with an ash layer, in which were found both wheel-made and "Negev" pottery. The wheel-made vessels belong to the standard repertoire of the 7th-6th centuries B.C. and include bowls, juglets, oil-lamps, cooking-pots, and flasks (fig. 12). Among the "Negev" pottery were oil-lamps and several small bowls. The northernmost room in the eastern casemate wall, which was especially rich in pottery finds, also yielded fragments of an ostracon, on which were a number of lines in ancient Egyptian writing. Two Hebrew ostraca were found in the central courtyard; the first features three consecutive letters (zayin, het, tet) and may be part of an alphabet (fig. 13). The second has four or five extremely blurred lines which have not yet been deciphered. As mentioned above, this late Iron Age fortress had been built over the remains of two earlier fortresses. The middle fortress (fig. 11 a) dates to the 8th-7th centuries B.C. Although it features a solid wall instead of casemate rooms, it seems to have had exactly the same groundplan as its successor—including projecting towers—and thus provides an earlier example of the towered-fortress type. The groundplan of the earliest fortress is still unknown, but it, too, had casemate rooms, and on the basis of its pottery it can be dated to the 10th century B.C. The excavations showed that this fortress had been erected on virgin soil." (The Iron Age Fortresses in the Central Negev, Rudolph Cohen, 1979 AD)

- We note here that Ussishkin rejects the idea that the fortresses were destroyed and rebuilt three times. Rather he takes the view of one continuous use that underwent two renovations: "In summary, it seems that the fortress was in use for a relatively long period of time, and the structures in it were rebuilt or changed three times, while the fortifications and the water system were continuously in use without interruption or change. We thus have here a good example of a monumental structure which lasted for a long time, while the adjoining domestic structures existed for a shorter period." (The Rectangular Fortress at Kadesh Barnea, David Ussishkin, 1995 AD)

F. Four ostracons were found at Qudeirat:

- This

ostracon was found in the youngest (highest) level about 700 BC. It is a

conversion chart between Hebrew and Egyptian numbering systems.

- "On the floor of one of the rooms, partially excavated last year, and located north of the southern casemate line, a large ostracon (Pl. 32:C) was discovered (max. length: 30 cm.; max. width: 22 cm.; average thickness: 5 mm.). Pieced together from 11 fragments, it is still incomplete, with four fragments obviously missing. While its study is in a preliminary stage, it is possible to state that the ostracon contains six vertical columns consisting mainly of hieratic numerals and weight symbols. The first column is apparently a list of units of measurement, similar to those employed in the well-known Arad ostraca. The second column, though partially missing or blurred, lists the hieratic numerals from 1 to 9, from 10 to 100 in units of tens and from 100 to 700 in units of hundreds. The third column con-tinues this list from 800 to 1000, again in units of hundreds, and from 1000 to 10,000 in units of thousands. In fact, the numerals 7000, 8000 and 9000 are missing, but can be surmised. Interestingly, the final figure (10,000) is indicated by the hieratic numeral 10 (A) and in Hebrew letters alafim (i.e. 'thousands). All these hieratic numerals in the second and third columns are preceded by the symbol of a unit of grain. In the fourth column, the counting recommences with 1. This list breaks off in a missing fragment, but then resumes, again from 1, but now preceded by the so-called 'shekel sign' (x), continuing to 40. The beginning of the fifth column is lost, but presumably included the numerals 50 and 60, preceded by the shekel sign. Intact are the numerals 70 to 100 in tens. and 100 to 900 in hundreds — all preceded by the shekel sign. This list concludes with the numerals 1000 to 4000 in thousands, but without the shekel sign. The beginning of the sixth column is similarly lost, but evidently contained the numeral 5000. The surviving portion lists the numerals 6000 to 10.000 in thousands, once again without the shekel sign. Detailed scholarly treatments of this important ostracon will shortly be published by A. Lemaire and H. Verenus. The author would like to state his preliminary opinion that, in view of the repetitive character of the list (with the numbers written several times, sometimes with shekel signs and sometimes without). the ostracon probably comprises a kind of exercise in scribal recording. Hieratic numerals have already appeared on other ostraca from Arad and elsewhere in Judah, but, unlike those scholars who see in the hieratic numerals an indication of either Egyptian control or mercenary troops, the author believes that they represent a purely cultural influence. This ex-plains why the Egyptian numerals appear together with the normal Hebrew signs for the shekel and the unit of one thousand." (Kadesh-Barnea, 1979, Rudolph Cohen, Israel Exploration Journal, 1980 AD, p 235-236)

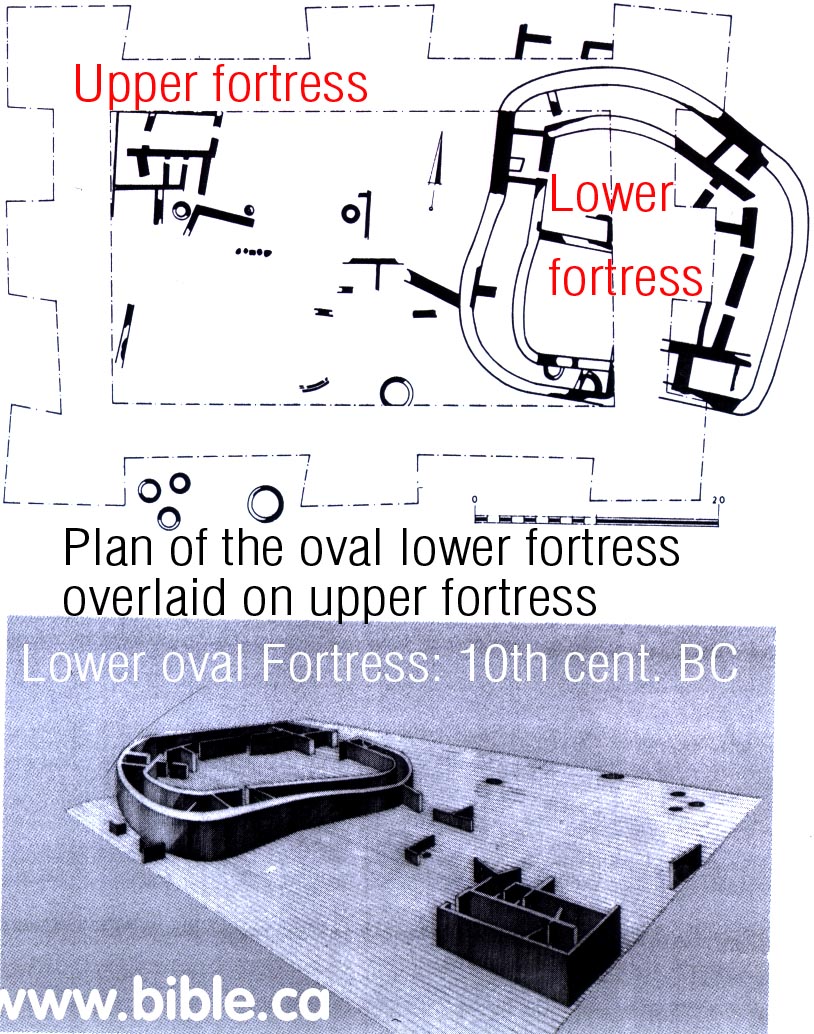

G. The oldest, oval fortress at Qudeirat on virgin soil: 950 BC

- The oldest

fortress is the oval one built by Solomon in 950 BC. Beneath the oval

fortress is virgin soil.

- "The earliest fortress on the site was erected seemingly on virgin soil in the 10th-9th centuries B.C.E. Its ground plan, as explained previously, has not been determined, but it evidently belonged to a wide-ranging fortress network then existing in the Central Negev. These fortresses begin near present-day Dimona, continue south past Yeroham and Sede Boger, skirt the edge of the erosion crater of Makhtesh Ramon, and then turn west; here they form a southerly line as far as Kadeshbarnea. Dozens of such fortresses have been located since the survey of Woolley and Lawrence, and many have been excavated over the past 12 years—mainly by the author sometimes in conjunction with Z. Meshel (Cohen 1970: 6-24; 1976: 3450; Meshel 1977: 110-35). The fortresses were built according to one of three distinct ground plans—being either roughly oval, rectangular, or square—but clearly belong to the same historical period. In the author's opinion, they were established by King Solomon. As is well known, he was a powerful and energetic ruler, who sought to consolidate the gains of his predecessor, David, by fortifying cities, constructing storehouses, and founding distant trading posts—such as Ezion-geber, on the Red Sea shores. Accordingly, a network of Central Negev fortresses would have served both in protecting the vital overland trade routes and in forming a bulwark against incursions from the south. An interesting parallel exists between this line of fortresses in the Central Negev and the description (Josh 15:1-4) of the southern limits of the tribe of Judah. Thus, these fortresses also define the southern border of Israel at the time of its greatest extent." (Excavations At Kadesh-Barnea: 1976-1978, Ein el-Qudeirat, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- "Previous to this season's excavations, the ground plan of the lowest, earliest fortress was unknown. This season, a new area was opened on the north-eastern side of the site, outside the walls of the later fortresses, and between two of their projecting towers. In this area were found the remains of casemate walls belonging to the earliest fortress. The outer wall is 1.5 m. wide, while the inner wall is only 0.9 m. wide. A 7-m. segment of this wall was exposed; it is curved, and continues underneath the foundations of the later fortress, giving the distinct impression that the ground plan is oval, like that of the nearby and contemporary fortress at 'El Qudeis. On the floor of the two casemate rooms, in a layer of ashes, was found a large number of pottery vessels, again belonging to two main types: wheel-made pottery characteristic of the tenth century B.C.E., among which should be especially noted two pithoi, three storage jars, two juglets and an oil lamp; and hand-made 'Negbite' pottery, including numerous fragments of cooking pots and kraters, and a complete chalice. Three iron arrowheads were also found in these rooms." (Kadesh-Barnea, 1979, Rudolph Cohen, Israel Exploration Journal, 1980 AD, p 235-236)

- "The walls of the third (earliest) fortress were uncovered only in the south-eastern corner of the mound. It seems that this fortress also had casemate rooms. A section of one of these rooms was exposed, the internal width of which was about 3 m. It emerged that this fortress had been erected on virgin soil. The pottery found in a layer of ashes on its floors again belongs to two types. The first consists of wheel-made pottery characteristic of the tenth-ninth centuries B.C., among which should be especially noted three complete vessels: a spouted juglet, a 'black juglet', and a pyxis. The second type is hand-made 'Negev' pottery including numerous fragments of bowls and kraters." (Kadesh-Barnea, 1978, Rudolph Cohen, Israel Exploration Journal, 1978 AD, p 197)

- "It seems that only a single rectangular fortress was built above the early oval one" (The Rectangular Fortress at Kadesh Barnea, David Ussishkin, 1995 AD)

- "The remains of the lowest, and earliest fortress are buried under some 4 m of debris, and its walls consequently were uncovered only in the southeastern corner of the tell. It appears, nevertheless, that this fortress also had casemate rooms. A section of one of these rooms was exposed, the inner width of which was ca. 3 m. The ground plan of this fortress has not yet been determined, but it apparently was established on virgin soil. The pottery, found in a layer of ashes that covered its beaten-earth floors, included both wheel-made and handmade types. The wheel-made vessels are characteristic of the 10th-9th centuries B.C.E., and particularly noteworthy among them were three undamaged items: a juglet with a spout, a "black" juglet, and a pyxis. The crude handmade pottery included numerous cooking-pot sherds." (Excavations At Kadesh-Barnea: 1976-1978, Ein el-Qudeirat, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

H. "Negevite" ware pottery found Ein El-Qudeirat:

- More on Negev Pottery.

- ""Negev" pottery cannot be used for dating purposes. On the contrary, it must be dated on the basis of wheel-made pottery found with it. The earliest Negev pottery has been dated in this way to about the 13th or 12th century B.C., the period of the Exodus. [note: the exodus took place in 1446 BC, not 1250 BC as Cohen thinks] Our excavations at Kadesh-Barnea indicate that Negev ware continued to be produced until the end of the Iron Age—that is, until the destruction of the First Temple in 587 B.C. The Negev ware found at Kadesh-Barnea included cooking pots, kraters, cups, and bowls of various kinds, some with knobs or ledge-handles, which seem to imitate wheel-made bowls from elsewhere in the country. Among the more unusual items, which have expanded the corpus of known "Negev" types, are three oil lamps, a small chalice and the incense burner, referred to above. These more experimental forms are associated primarily with the later levels of the site." (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

I. The problem of no evidence of the Exodus period at Ein El-Qudeirat:

- It is important to realize that the four springs at the Quseima area have been in continuous use from before the time of Abraham. We do not doubt that evidence will one day be found that predates the Solomonic fortress network. The problem is that this evidence must specifically show that the Hebrews were here for 38 years between 1444 and 1406 BC.

- "The problem of Kadesh-Barnea is simply stated: Has the site been correctly identified? If so, why have we found no remains from the Exodus period?" ... "But, where are the remains from the time of Moses (and of Abraham), from the period of the Exodus, and from the era of the Judges which we would expect to find if this site is, indeed, Kadesh-Barnea? Thus far our excavations have yielded nothing earlier than the tenth century B.C.—the time of King Solomon." (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- "How can we explain this? First of all, the identification of the site is not absolutely certain. The strategic location of the fortress is certainly what we could expect if it is Kadesh-Barnea, the border settlement described in Joshua 15:1-3. On the other hand, we have no written evidence, such as ostraca, establishing that this was the border settlement referred to in Joshua." (Did I Excavate Kadesh-Barnea? absence of Exodus remains poses problem, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- "Whereas the Beer-sheba Basin remained inhabited throughout the Iron Age, the central Negev was settled only during the period of the United Monarchy, when (especially) King Solomon seems to have followed a deliberate pattern of expansion and of construction of forts. After the 10th century, the southern border of Judah receded: Cohen discovered that all the Iron Age sites in the Central Negev contained remains which dated only to the 10th century." (Kadesh Barnea: Judah's Last Outpost, Carol Meyers, 1976 AD)

- Dothan gives his evidence for the settlement that existed before the first fortresses were built by Solomon. This evidence is based solely on Negev ware Pottery: "The Pre-Fortress Finds: Most of the finds in this group are sherds of hand-made vessels (Pl. 30, A). The ware is coarse and the clay mixed with straw. The firing is mediocre and the vessels are never slipped. Most of the pottery are deep bowls with flat or thickened rims (Fig. 4 : 1-5) . In addition, hole-mouth jars and store-jars with thick rounded rims, flaring outwards or inwards, were found (Fig. 4 : 6-10) . Some of the bowls and hole-mouth jars had pairs of ledge handles below the rim or high up on the sides (Fig. 4 : 12-17; P1. 30, B); only one loop-handle was found. On one of the hole-mouthed jars a potter's mark appears (Fig. 3 : 11) . Prior to the excavations at Kadesh-barnea, no material of this sort had been reported from other Palestinian sites, with the exception of a vessel discovered in the excavation of Etzion-geber3 and described by Prof. N. Glueck as a 'crucible'. Glueck identified the vessels found at Kadesh-barnea with those unearthed in the lowest level at Etzion-geber. Vessels of this type were later found by Dr. Y. Aharoni during a survey at `Ein Qudeis, and especially at Ramat Matred in the central Negev4. At all these sites, pottery of this type dates from the 10th century or the start of the 9th century B.C.E." (The Fortress at Kadesh-Barnea, M Dothan, 1965)

- "Dothan identified three periods of occupation: a pre-fortress period, containing only hand-made pottery which he dated to the 10th century; the fortress itself with pottery from a very long time-span — the 9th to the 7th centuries; and a post-fortress period of scattered Persian remains." (Kadesh Barnea: Judah's Last Outpost, Carol Meyers, 1976 AD)

- Cohen dismisses the view of Dothan of the "pre-fortress" period based upon Negev Pottery alone: "Dothan discovered no indication of different building phases during the time of the fortress's existence, but he recognized both pre- and postfortress settlement periods on the site. The pre-fortress findings consisted of crude handmade pottery—mainly bowls, deep pots, and hole-mouth jars. Although these sherds could not be connected with wheel-made vessels or building remains, he dated them, on the basis of similar pottery finds at Ezion-geber, Ramat Matred, and elsewhere in the Negev, to the 10th or early 9th century B.C.E. (Dothan 1965: 139; 1977: 697)." (Excavations At Kadesh-Barnea: 1976-1978, Ein el-Qudeirat, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

J. Cohen and Meyers discuss the lack of Exodus evidence:

- "The earliest remains on the site derive from the 10th century B.C.E. the age of David and Solomon. In the Bible, however, Kadesh-barnea is connected with the much earlier epoch of Moses and the 40-year wandering. This is an apparent inconsistency, and it should be asked if the excavations at Kadesh-barnea have contributed, in one way or another, to the understanding of Israel's early traditions. It should be stated clearly at the outset that the answer to this is equivocal. It could be argued that the lack of any evidence for pre-10th-century B.C.E. settlement on the site supports the position of those who maintain that there is no historical basis for the early traditions of the Old Testament—specifically, in this case, for those concerning Moses and the wanderings in the desert. Before reaching this conclusion, however, some cautionary considerations should be kept in mind. First, the identification of the site is not absolutely certain. Although the author is convinced that the site of Tell el-Qudeirat is Kadesh-barnea, documentary evidence is lacking. The excavations, furthermore, have reached virgin soil in only very restricted places on the tell, and if there are earlier remains, they might not have extended over the entire area of the later fortresses. Apart from this, the author believes that there may be a connection between the concentration of settlements from MB I throughout the region in question and the biblical tradition of a prolonged sojourn at Kadesh barnea. Leaving these issues aside, the mere fact that, of all the numerous Iron Age fortresses in the Central Negev, Kadesh-barnea alone was rebuilt twice is in itself highly intriguing. This may, of course, be explicable on the basis of its strategically important location at the junction of two main desert routes. But it is also possible that the site was particularly sacred to the Israelites of the Monarchy because of its association with the traditions of Exodus and therefore had a religious, as well as practical, role. " (Excavations At Kadesh-Barnea: 1976-1978, Ein el-Qudeirat, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- "Only a small portion of Solomon's Fortress has been excavated, so there may still be new surprises and information available: "Below the earlier fortress are 10th-century remains. So far these have been recovered only in one pit, and it cannot yet be ascertained whether these remains are also part of a fortress. Only further excavation will determine this. But in general, the depth of debris has been surprising the deepest trench has already uncovered 6 m. of debris, and virgin soil has yet to be reached." (Kadesh Barnea: Judah's Last Outpost, Carol Meyers, 1976 AD)

K. Our assessment of Cohen's and Meyers' views on the lack of Exodus evidence:

- Although the oldest oval fortress was excavated by Cohen, there are sections of the two younger fortresses that have not excavated down to virgin soil. Cohen expects to find exodus period (1444 BC) evidence under the areas of the older fortresses that have not yet been excavated down to virgin soil level.

- Cohen suggests that the reason Qudeirat is the only one of three fortresses in the Quseima area that was rebuilt twice, is for sentimental reasons, since it was Kadesh Barnea. In other words, the fortresses were memorial structures in addition to military outposts. While this is possible, it is unlikely, since nothing has been discovered in any of the three forts that were built, that suggests the location was Kadesh. It such had been found, we would surely have heard about it!

- So that is the sum of the archeological evidence that Kadesh is located at Qudeirat: "Nothing yet, but lets keep digging" and the fact it is the only fortress Solomon built that was rebuilt twice because of its sentimental connection with the 38 years Israel spent there while sojourning in the wilderness before they entered the promised land. Need we remind you that Qudeirat was located 28 KM inside the formal stated border of the promised land: Wadi el-Arish?

L. Why was Qudeirat built three times:

- Qudeirat was the only fortress Solomon built, that was rebuilt two additional times, with the exception of Ezion-Geber, which was rebuilt once.

- Cohen says: "it is also possible that the site was particularly sacred to the Israelites of the Monarchy because of its association with the traditions of Exodus and therefore had a religious, as well as practical, role." (Excavations At Kadesh-Barnea: 1976-1978, Ein el-Qudeirat, Rudolph Cohen, 1981 AD)

- The reason Qudeirat was rebuilt twice (three buildings) is not for sentimental reasons, as Cohen suggests, but because of the large water supply. Remember there were four springs in the Quseima area.

- What is true today in Israel was true in 950 BC: "Its all about the water"

- We find Cohen's opinion to be wishful thinking in light of the fact that he admits nothing from the exodus has ever been found there.

- The real reason why the fortress at Qudeirat was rebuilt twice: Simply put, it was Israel's claim of sovereignty over the two eastern springs at Qudeirat and Qedeis. Egypt had control and sovereignty over the two western springs at Quseima and Muweileh. There was obviously an agreement between Egypt and Israel to share the water resources. Qudeirat was Israel's "stake in the ground" that guaranteed their half share of the water at the largest oasis in the Sinai.

- At the time of Solomon, Israel's border extended all the way to the Wadi el-Arish. However, after Pharaoh Shishak destroyed the entire network of fortresses, the border moved east to share the water. At that time, Egypt and Israel agreed that the border divided the springs so that each had two, Qudeirat is the location that the Jews built to protect the water at Qudeirat and Kades. Egypt would get the water from the springs at Quseima and Ein Muweileh. It also divided the control of the four ancient trade routes that intersected just west of Qudeirat. So you have the Egyptians on the west of this major crossroads of traffic and two springs completely under their control and the Hebrews on the east of the major crossroads with two springs of their own. Qudeirat represented the western most point of control of the Judean kingdom under Uzzah and Josiah. Qudeirat was the "border town" between Egypt and Israel after 900 BC.

- We reject Cohen's suggestion that sentimentality is why Qudeirat was rebuilt twice. Remember, the springs in the Quseima area were the largest in the entire modern Sinai Peninsula. Qudeirat was the largest of the four springs, need we say more? It is obvious why Qudeirat was built three times! Its all about the water!

M. Radiocarbon dating of Qudeirat: Hendrick J. Bruins, Johannes van der Plicht

- For an examination of radiocarbon dating see click here.

- The science of radiocarbon dating and the process which dates are selected is rather unreliable at best. Typically a single sample will be tested and retested until a date close to what the person who submitted it is looking for is produced. Then, that result is chosen as "the date" even though 20 other dates were rejected. This is well documented, but not well known by the general public. For example "1470 Scull" was tested over 40 times until they got the date they were looking for. Skull 1470 discovered by Richard Leakey is supposed to be an ancestor to man, too. Leakey and others obtained 41 potassium-argon dates for this skull, all of which they rejected because the date obtained was not "right"? Finally Leakey used an argument based on the size of pigs teeth found in the strata to get the date for skull 1470 that he thought was correct. Here is a discussion specifically about radiocarbon 14 dating.

- In 2005, Hendrick J. Bruins, Johannes van der Plicht published their analysis of the three fortresses in light of Radiocarbon dating tests conducted on all three fortress levels including other sites in the Negev.

- In summary, they vindicated Cohen's view that there were three distinct levels of occupation (not two) separated by periods of non use. Regarding the upper fortress, they vindicated Cohen's date and that it was destroyed in 586 BC by Babylon. The middle and lower fortresses, however, they shifted the dating to about 150 years old. In other words, based upon radiocarbon dating, they suggested, that the middle square fortress was built by Solomon and destroyed by Shishak and the lower fortress was built about 1100 BC. Cohen said that the lowest/oldest oval fortress was built by Solomon and destroyed by Shishak.

- The radiocarbon dates that Bruins and van der Plicht came up with do provide, on face, a rather shocking rebuke of Ussishkin's/Finkelstein's view that there are two occupation levels, the earliest being long after Solomon died. What is more sure, is that there are three occupation dates. What is less sure, is the relative dating of all three. In other words, given the nature of all radiometric dating, specific dates are always less important than relative dates from a single site.

- Even Bruins and van der Plicht admit that the presence of charcoal on the site would give a slightly older date than the actual date: "We note that the old-wood effect may lower the date to some extent at Tell el-Qudeirat" (The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, Thomas E. Levy, Higham, Bruins, Plicht, 2005, p362) Given the fact that the lowest fortress was indeed burnt with fire, this by their own admission, reduce the 150 years with which they differ with Cohen.

- The radiocarbon dates do not help in identifying the site as Kadesh Barnea, since there is still a 300 year gap of occupation from the first oval fortress back to the exodus of 1446 BC.

- "The 14C date associated with the destruction of the Middle Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat is considerably older (10th-9th centuries BCE in the 1a range) than the age suggested by Cohen (1983, 1993a) in the mid-7th century BCE. One radiocarbon date of a destruction layer outside the eastern revetment wall is certainly a reason to regard the result as preliminary with regard to the Middle Fortress. Yet the four radiocarbon dates of the three fortresses are internally coherent in terms of stratigraphy and must he taken into account. In terms of possible regional correlations between architecture and governmental planning, it should he noted that both Stratum V and IV of Tel Beer Sheva had a solid wall, like the Middle Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat. Casemate walls built on top of the remains of the previous solid walls occur at Tel Beer Sheva in Stratum III (Herzog 1993) and at Tell el-Qudeirat with the Upper Fortress (Cohen 1983, 1993a). Herzog (1993) suggested that Stratum V of Tel Beer Sheva-characterised by a solid wall—might have been destroyed by Pharaoh Shishak. The only "C date from Tell el-Qudeirat that might fit the Shishak campaign is the destruction layer associated with the Middle Fortress, which also had a solid wall. The elliptical Lower Fortress was smaller and had a different shape than the rectangular Middle and Upper Fortresses at Tell el-Qudeirat, which are decisively younger in age. Most Iron Age settlements in the Negev-Sinai region are characterised by elliptical or irregular shaped fortresses, including Horvat Haluqim, Nahal Ha'Elah and the Lower Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat. The most probable calibrated 14C date of 1103-1050 BCE for the destruction of the Lower Fortress is about 150 years older than the suggested date for its destruction by Cohen (1980, 1983, 1993a). The above '4C date would place the Lower Fortress firmly in the Iron I period, as favoured by Rothen-berg (1972, 1988), Aharoni (1978), Herzog (1983), Finkelstein (1984, 1988) and considered possible by Meshel (1979). We note that the old-wood effect may lower the date to some extent at Tell el-Qudeirat. However, the powdery charcoal mixed with soil from the destruction layer of the Lower Fortress is generally not characteristic for old wood. Large trees of an old age tend to give chunks of recognizable woody charcoal, such as found often at Tel Dan. But even the radiocarbon results from such woody charcoal at Tel Dan are only rarely older than 50 or 60 years in comparison to short-lived seeds (Bruins et al. [Chapter 19, this volume]). Therefore, particularly in arid regions, usually devoid of trees, the inherent age of fine charcoal is in most cases probably not more than 10-30 years, or even much less. Annual vegetation growing after the winter rains withers in the spring. Burning of such vegetation would give short-lived powdery charcoal similar in age to seeds. Desert shrubs are older than annual plants and charcoal derived from such shrubs may have an age of ca. 2 to 20 years, occasionally even older, but on average below 10 years. Though the exception may always be present, a small to medium old-wood effect is probably the rule." (The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, Thomas E. Levy, Higham, Bruins, Plicht, 2005, p362)

- "The Lower Fortress: The oldest archaeological remains discovered at Tell el-Qudeirat were found at a depth of about 5 m below the surface of the mound. The Lower Fortress had an elliptical ground plan, about 27 m in diameter, with casemate rooms around a central courtyard. In addition, several buildings and silos were found to the west of the fortress. Many types of pottery vessels were found in the ash covered floors of the casemate rooms (Cohen 1983, 1993a). The excavator (Cohen 1980, 1983, 1993a) suggested that the Lower Fortress was established during the reign of Solomon and destroyed in the course of Pharaoh Shishak's campaign, all in the 10th century BCE. The western profile of Square K-67 in the centre of tell el-Qudeirat, which exhibited the upper-most destruction layer 50 cm below the surface of the tell, also exposed the lowermost destruction layer at a depth of about 5 m. A sample of fine powdery charcoal mixed with soil was taken from this destruction layer by the first author, again in 1981, in cooperation with Cohen, who considered this layer to represent the destruction of the Lower Fortress. The dark ash layer, about 10 cm thick, covered a 20 cm thick layer of loessial soil, also containing a few pieces of charcoal, indicating past human activity predating the dark ash layer. Below the loessial soil lies a 'virgin' layer of fine gravel mixed with sandy loam (Bruins 1986). The fine charcoal sample from the ash layer was measured in Groningen and yielded a radio-carbon date of 2930 ±. 30 BP (GrN-12330, Fig. 21.6). The la calibrated age ranges are 1210-1200 (5.5%), 1191-1177 (8.1%), 1162-1141 (12.7%), 1131-1107 (13.3Vo), 1103-1050 (28.6%) BCE. The 2a calibrated ages are 1258-1235 (6.5%), 1215-1016 (88.9%) BCE. The most probable calibrated age range of 1103-1050 BCE would place the destruction layer in the first half of the 11th century BCE, which is about 150 years older than the suggested destruction, according to Cohen, by Shishak around 925 BCE. Alternative "C dating options, albeit of lower relative probability, include the 12th century and even the 13th century BCE, while the 11th century BCE is the youngest possible date in the 2o range. A possible old-wood effect of the charcoal is unlikely to move the date into the first half of the 10th century BCE, as this would require a lowering of the date by about 150 BP years. It was shown from the Upper Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat that the difference between charred seeds and fine charcoal can be quite small, that is, only 20 BP years!" (The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, Thomas E. Levy, Higham, Bruins, Plicht, 2005, p356)

- "Comparing the Iron Age 14C dates from Sinai and Negev with those from Khirbet en-Nahas in the eastern Arabah Valley in Jordan (Levy et al. 2004), it is quite remarkable that grosso modo [in a rough way] a similar BP time range is found for the older part of the Iron Age. The oldest dates are 2930 ± 30 BP (GrN-12330) in relation to the Lower Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat and 2906 ± 39 BP (HD-14057) concerning the Slag Mount East (Hauptmann 2000). Moreover, also the period 2880-2825 BP appears in both areas." (The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, Thomas E. Levy, Higham, Hendrick J. Bruins, Johannes van der Plicht, 2005, p363)

- "In conclusion, the radiocarbon dates from the three successive fortresses at Tell el-Qudeirat are internally consistent in stratigraphic terms. The results indicate that the Upper Fortress was probably destroyed by the Babylonian campaigns, as suggested by Cohen, though a 601/600 BCE historical destruction date would fit better than the alternative 586 BCE option. The Middle Fortress appears older than suggested by Cohen. It is the only radiocarbon date that can possibly be linked, in chronological terms, with the Shishak campaign. The thick solid wall of this fortress appears similar in architectural construction to that of Stratum V of Tel Beersheba, the destruction of which is also associated with the Shishak campaign (Herzog 1993). The Lower Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat and the Nahal Ha'Elah Fortress, both elliptical in shape, have destruction layer dates that appear older than the Solomonic period. The possible old-wood effect must be taken into consideration, but fine charcoal tends to be rather short-lived. If the old-wood effect is minimal, even the 12th century BCE is a reasonable option for the Lower Fortress at Tell el-Qudeirat in terms of its radiocarbon date. Considering all the different theories proposed for the elliptical Iron Age fortresses and related settlements, briefly presented in the introduction, it seems that the suggested chronologies and historical associations by Cohen and Haiman are the most unlikely, while the 11th and early 10th centuries BCE appear most probable. However, even older dates for the beginning of these settle-ments cannot be ruled out, as the radiocarbon dates were derived from destruction layers. Indeed, the oldest date obtained so far, from the agricultural soil layer at the site of Horvat Haluqim, backs the above picture. Here the old-wood effect cannot be used as an excuse, because the date is based on a sheep or goat bone from within the anthropogenic agricultural soil layer. Nevertheless, more dates are necessary to substantiate and refine this preliminary radiocarbon dating assessment." (The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, Thomas E. Levy, Higham, Bruins, Plicht, 2005, p364)

Conclusion:

- There are ten very good reasons why Qudeirat cannot be Kadesh Barnea. (see above)

- There is no evidence from any ancient written source or tradition that Kadesh Barnea is located at Qudeirat or anywhere near the Quseima area.

- We expect to one day find archeological evidence at all of the four Quseima area springs that predates Solomon. These springs did not first start being used just because Solomon built three fortresses here in 950 BC. The evidence, however, must be specifically "Hebrew" from the time of 1446 - 1406 BC.

- Kadesh Barnea is located at or near Petra.

- Click here to learn the true location of Kadesh Barnea!

|

Chronological History of the search for Kadesh 2000 BC - 2009 AD |

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.