Bedlam: "A madhouse by any other name is still a jail!"

The most famous mental hospital in history. 1677 - 1815 AD

"I think it is a very hard case for a man to be locked up in an asylum and kept there; you may call it anything you like, but it is a prison." (Sir James Coxe, testimony before the House of Commons Select Committee on the Operations of the Lunacy Laws, 1877)

See also: History of Psychiatry homepage

See also: History of Psychiatry homepage

"The rattling of Chains, the Shrieks of those severely treated by their barbarous Keepers, mingled with Curses, Oaths, and the most blasphemous Imprecations, did from one quarter of the House shock her tormented Ears while from another, Howlings like that of Dogs, Shoutings, Roarings, Prayers, Preaching, Curses, Singing, Crying, promiscuously join'd to make a Chaos of the most horrible Confusion:" (The distress'd orphan or, Love in a mad-house, a fictional play based upon bedlam, Eliza Haywood, 1726 AD, p 40-43)

Introduction:

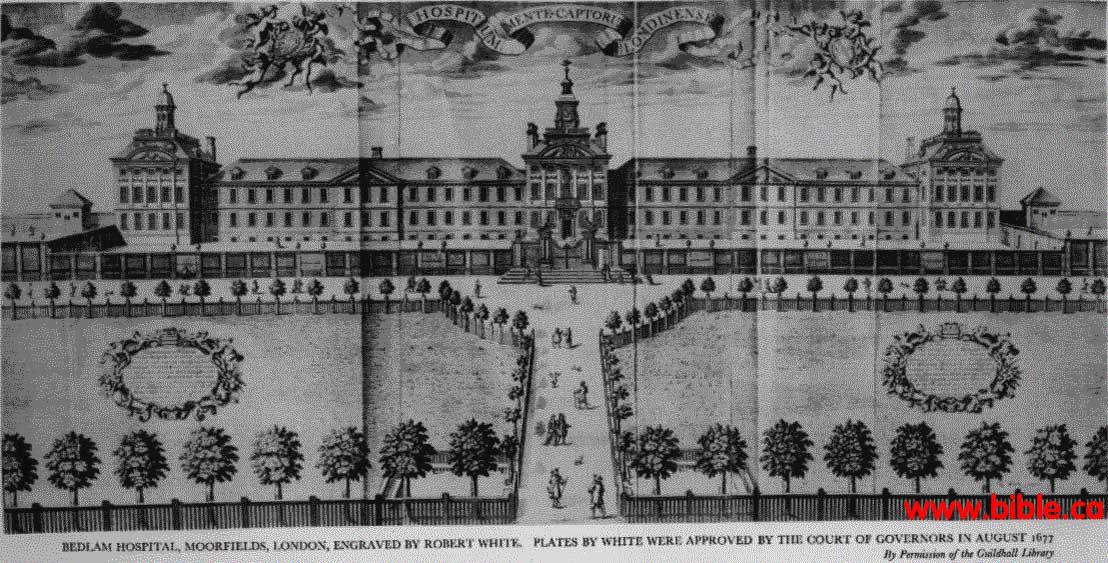

The word bedlam means a state of uproar, confusion, chaos and anarchy and has its origin from the name of the most famous mental hospital in history: The Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, London England. It was known as Bethlehem, because it was started in 1247 AD as a religious Priority house by Order of the Star of Bethlehem. It changed into a hospital in 1330 AD and admitted its first mental patients in 1357 AD. In 1677 AD, a large hospital was built (pictured above) and this became the infamous "Bedlam"!

Bedlam was like what Jesus called a Whitewashed wall. It looked real good on the outside, but inside it was a living hell. Just as the families of the insane cast their "dirty laundry" inside Bedlam in order to make their own lives look clean, so too the outside of Bedlam was stately and ornate which salved and deceived the conscience into ignoring the tortures happening within. The insane were not allowed on the ornate front lawn of the building, proving that everything about Bedlam was designed for the benefit of the families of the insane, and nothing was for the benefit of the insane that were jailed there.

"In constructing the new Bethlem at Moorfields in the late seventeenth century, 'the Governors had been much more concerned with "the Grace and Ornament of the ... Building" than with the patients' exercise or any other therapeutic purpose. Patients had actually been forbidden to walk in the front yard and gardens of new Bethlem, as apparently was originally intended, simply because its front wall would have had to be built so high (to prevent escape) that the view of the hospital "towards Moorefields lyeing Northwards" would be spoiled. New Bethlem was constructed pre-eminently as fund-raising rhetoric, to attract the patronage and admiration of the elite, rather than for its present and future inmates, whose interests took a poor second place. Nor did contemporaries fail to perceive and remark upon the ironic antithesis between the sober splendour of the hospital's palatial exterior and the impoverishment and chaos that lurked within.' J. Andrews, 'Bedlam Revisited', pp. 174-5." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 22)

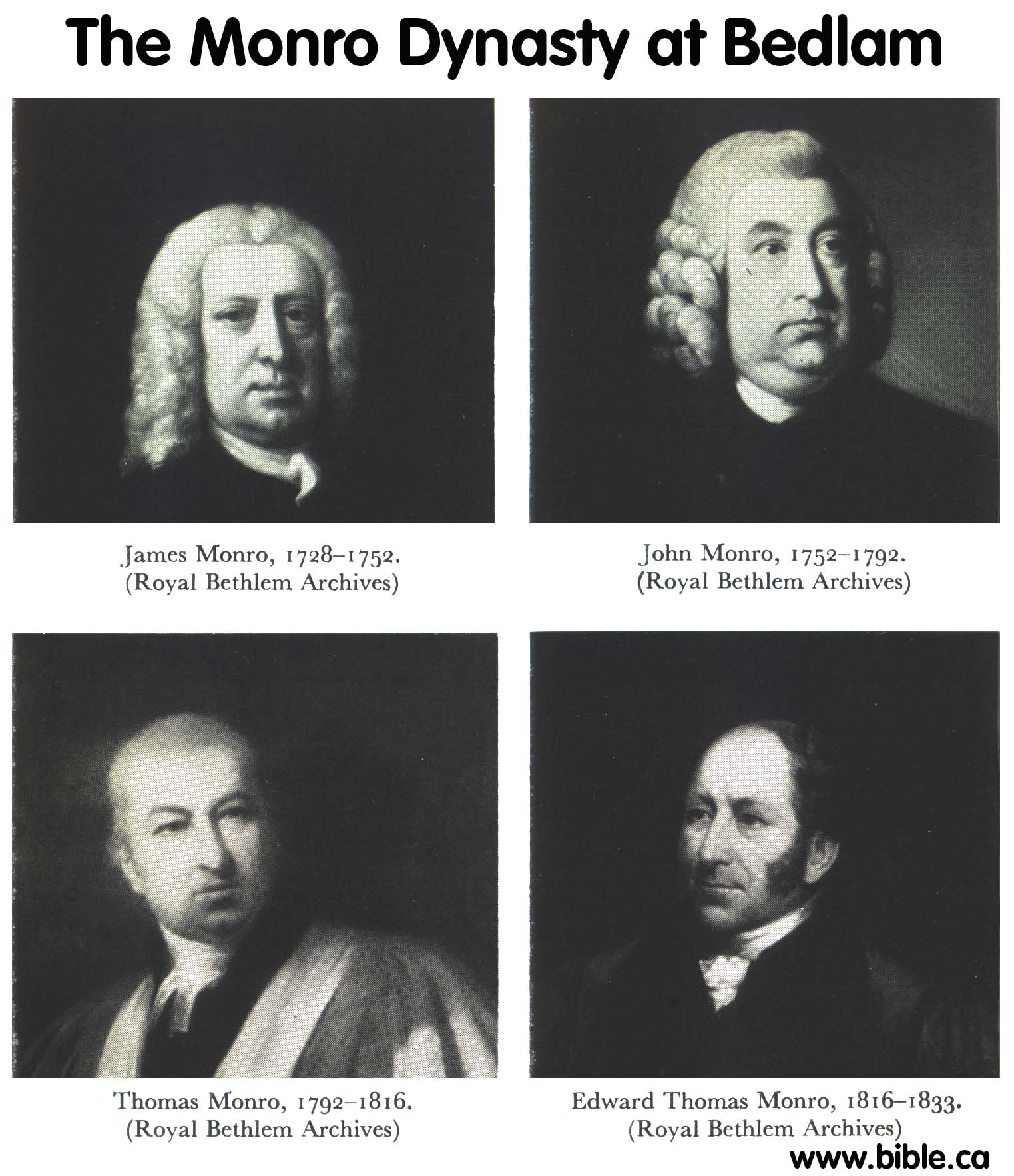

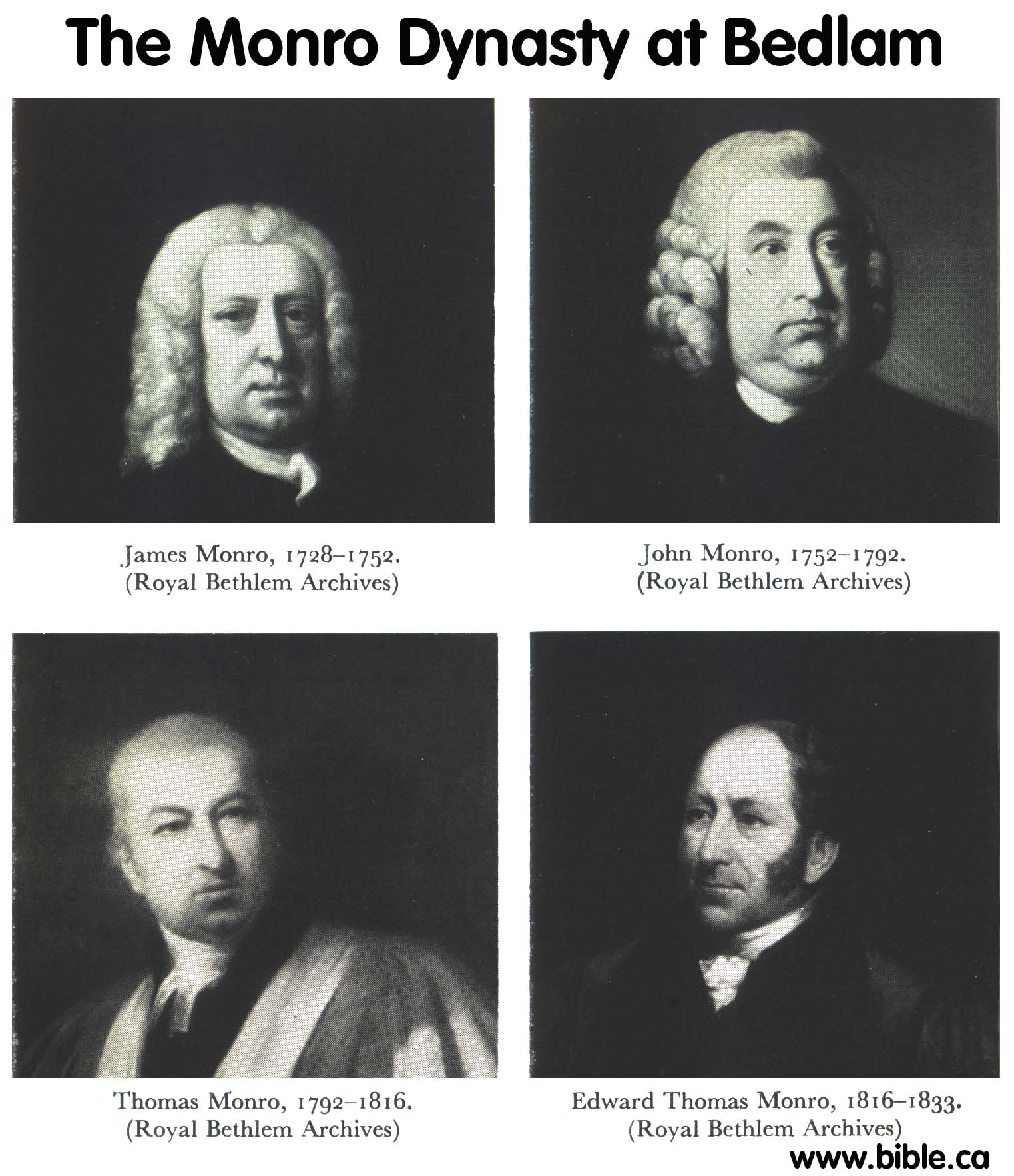

Three generations of Monro's were in charge at Bedlam starting with James in 1728, then John in 1751, then Thomas in 1787. The dynasty ended with the firing of the last Thomas Monro in 1815, after the government documented the horrors that took place at Bedlam.

William Battie worked at Bedlam for about ten years under John Monro, after which he quit and started up a competing mad house called "St. Luke's" mental hospital in England in 1751 AD. After St. Luke's began, there were still only two public asylums in England.

"The birth of the asylum in its turn was intimately bound up with the emergence and consolidation of a newly self-conscious group of people laying claim to expertise in the treatment of mental disorder and asserting their right to a monopoly over its identification and treatment. It is with this increasingly organized specialism that this book is concerned. We seek to understand the growth and development of a collective consciousness and organization among a subset of medical men, the ancestors of the modern profession now called psychiatry." (The Transformation Of The Mad-Doctoring Trade, Andrew Scull, 1994 AD, p 3)

The modern slur of "Bedlam" was created at the "Bedlam mad house" under the direction of John Monro between 1752-1791 AD. "The almost four decades during which Monro presided as physician at the Bethlem and Bridewell Hospitals, 1752-91, constituted a momentous period in Bethlem's history. It was in the eighteenth century that Bethlem as "Bedlam" truly assumed its archetypal place as a by-word for all things mad and chaotic. Not only did Bedlam become a medium for satirizing the follies of the nation, but it was also in the same period that Bethlem really began to generate its own history of scandal and vilification. As part and parcel of such developments, the Monros themselves would be depicted as the quintessential mad-doctors by famous poets and playwrights, as well as the not so famous Grub-Street scribblers, cartoonists, and pamphleteers." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 20)

Pinel worked in a mad house in France that rejected the torture practiced at Bedlam at the same time. He rejected that insanity was a bodily disease and practiced moral treatment to cure. He had little faith in drugs since he correctly understood that insanity is a spiritual problem, not physical. His kinder, gentler approach was a dramatic contrast to Bedlam: "Derangement of the understanding is generally considered as an effect of an organic lesion of the brain, consequently as incurable; a supposition that is, in a great number of instances, contrary to anatomical fact. Public asylums for maniacs [like Bedlam] have been regarded as places of confinement for such of its members as are become dangerous to the peace of society. The managers of those institutions, who are frequently men of little knowledge and less humanity, have been permitted to exercise towards their innocent prisoners a most arbitrary system of cruelty and violence; while experience affords ample and daily proofs of the happier effects of a mild, conciliating treatment, rendered effective by steady and dispassionate firmness." (A Treatise on Insanity, Philippe Pinel, 1806 AD)

Pinel describes how his moral treatment was superior to the tortures at Bedlam: "In the preceding cases of insanity, we trace the happy effects of intimidation, without severity; of oppression, without violence; and of triumph, without outrage. How different from the system of treatment, which is yet adopted in too many hospitals, where the. domestics and keepers are permitted to use any violence that the most wanton caprice, or the most sanguinary cruelty may dictate. In the writings of the ancients, and especially of Celsus, a sort of intermediate and conditional mode of treatment is recommended, founded, in the first instance, upon a system of lenity and forbearance; and when that method failed, upon corporal and physical punishments, such as confinement, chains, flogging, spare diet, &c. (p) Public and private mad-houses, in more modern times, have been conducted on similar principles." (A Treatise on Insanity, Philippe Pinel, 1806 AD)

"At least until the seventeenth century, Bethlem remained the only specialized receptacle of this kind, and provision there was on an exceedingly modest scale. (In 1403-4, the inmates consisted of six insane and three sane patients, and this number grew only slowly in the following centuries. In 1632, for example, it was reported to contain twenty-seven patients, and in 1642, forty-four.)' In other parts of the country, some of the insane who posed a particularly acute threat to the social order, or who lacked friends or family on whom they could call for support, were likely to find themselves, along with the 'sick, aged, bedridden, diseased, wayfaring men, diseased soldiers and honest folk fallen into poverty', cared and provided for within the walls of one of the many small medieval `hospitals'.' Custody for others who proved too violent or unmanageable to maintain in the community was provided by the local jail." (The most solitary of afflictions: madness and society in Britain 1700-1900, Andrew Scull, 1993 AD, p 11)

A. The Monro dynasty:

Three generations of Monro's were in charge at Bedlam. The dynasty ended with the firing of the last Monro, after the government documented the horrors that took place at Bedlam.

"John Monro was without question one of the most famous mad-doctors of his generation. Besides his position at Bethlem Hospital, he was also a major figure in the emerging private "trade in lunacy" that was so notable a feature of eighteenth-century England's burgeoning consumer society. Monro attended Bethlem at a time when the hospital's custom of exposing the insane to the eyes of sightseers reached its apogee. In the last years of his tenure as its physician, the practice was radically curtailed-though not at his initiative-after a wave of public, literary, and media protest. Recognized by contemporaries as a leading authority on insanity, Monro's close social connections with members of the aristocracy and gentry, as well as with medical professionals, politicians, and divines, ensured for him a significant place in the social, political, cultural, and intellectual world of his time." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xiv)

"Monro's attendance (as well as his father's) on Alexander "the Corrector" Cruden, the famous compiler of a Bible concordance that remains in print to this day, brought him notoriety of a different sort: a torrent of published criticisms from the disaffected patient that constituted one of the first examples of a persistent tradition of protest literature directed against the claims of mad-doctoring (and, later, psychiatry) to be engaged upon a therapeutic enterprise. The case is examined here (in chapter 3) as part of the tangled set of relationships between religion and insanity in this period: in particular, between those who appeared to suffer from this especially problematic admixture, and the doctors, divines, and laymen who, alternately, ministered to and vilified them. The Monros' tendencies to stigmatize religious enthusiasts as crazy, and their medical treatment of Methodist madmen, was to bring down opprobrium on their heads from the movement's leaders, John Wesley and George Whitefield. (Sympathy for popular religious enthusiasm was in rather short supply among the ultra-orthodox "Bethlemeical" physicians, with their family history of high Anglican, Tory, and Jacobite sympathies.)" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xv)

"John Monro was without question one of the most famous mad-doctors of his generation. Besides his position at Bethlem Hospital, he was also a major figure in the emerging private "trade in lunacy" that was so notable a feature of eighteenth-century England's burgeoning consumer society. Monro attended Bethlem at a time when the hospital's custom of exposing the insane to the eyes of sightseers reached its apogee. In the last years of his tenure as its physician, the practice was radically curtailed-though not at his initiative-after a wave of public, literary, and media protest. Recognized by contemporaries as a leading authority on insanity, Monro's close social connections with members of the aristocracy and gentry, as well as with medical professionals, politicians, and divines, ensured for him a significant place in the social, political, cultural, and intellectual world of his time." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xiv)

"Monro's attendance (as well as his father's) on Alexander "the Corrector" Cruden, the famous compiler of a Bible concordance that remains in print to this day, brought him notoriety of a different sort: a torrent of published criticisms from the disaffected patient that constituted one of the first examples of a persistent tradition of protest literature directed against the claims of mad-doctoring (and, later, psychiatry) to be engaged upon a therapeutic enterprise. The case is examined here (in chapter 3) as part of the tangled set of relationships between religion and insanity in this period: in particular, between those who appeared to suffer from this especially problematic admixture, and the doctors, divines, and laymen who, alternately, ministered to and vilified them. The Monros' tendencies to stigmatize religious enthusiasts as crazy, and their medical treatment of Methodist madmen, was to bring down opprobrium on their heads from the movement's leaders, John Wesley and George Whitefield. (Sympathy for popular religious enthusiasm was in rather short supply among the ultra-orthodox "Bethlemeical" physicians, with their family history of high Anglican, Tory, and Jacobite sympathies.)" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xv)

B. A gladiator spectator sport!

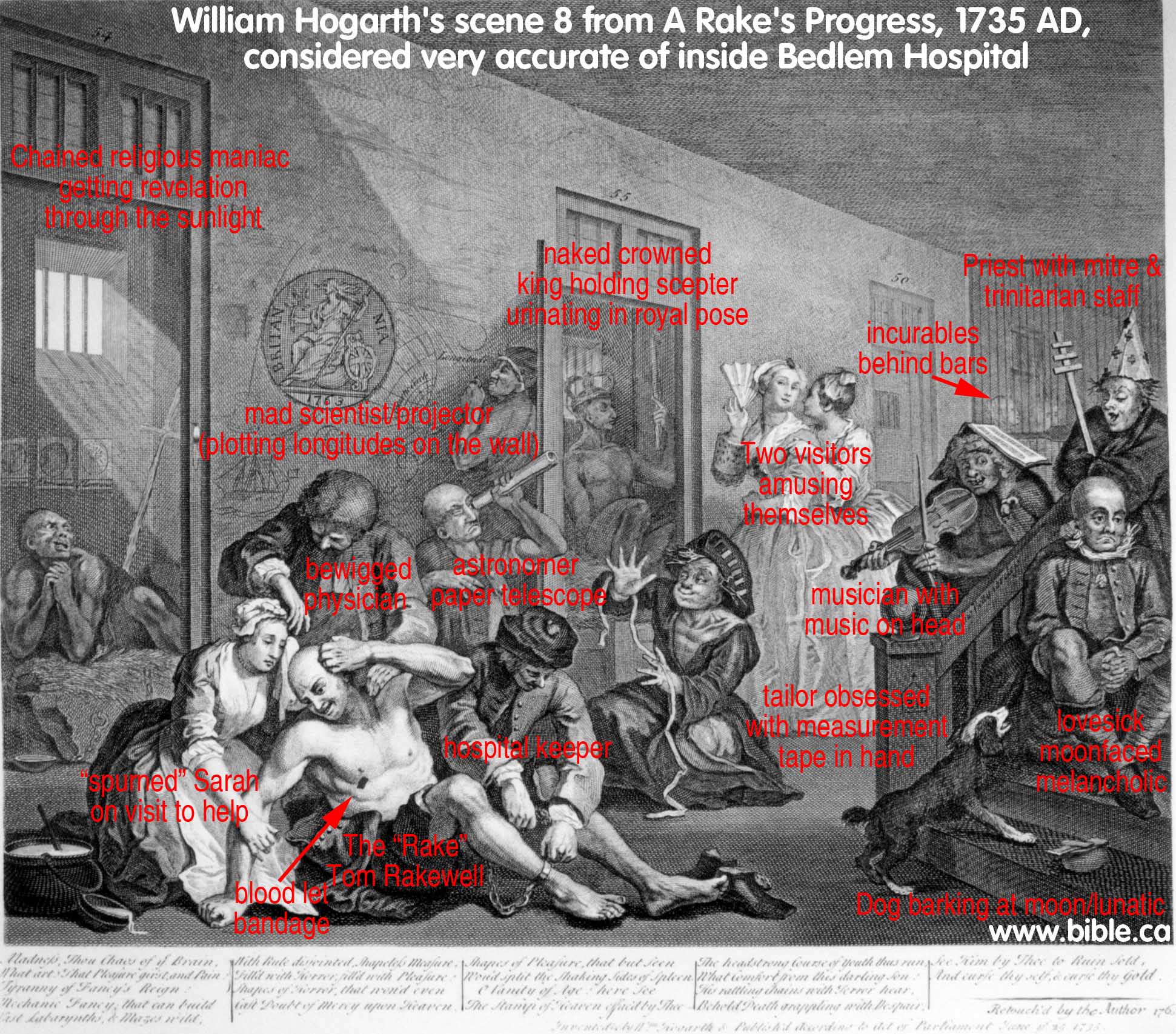

Under the oversight of John Monro, Bedlam became a kind of "modern gladiator sport" of the 1750's. For entertainment purposes, the general public would actually pay an admission fee and have free run of the mad house. Once inside, they literally "made sport" of those chained to wall, floor and locked behind bars in tiny dirty rooms. They got pleasure out of provoking the caged humans into anger by teasing, mocking and even throwing objects at them. The injustice was too much for the inmates and they often reacted violently with loud screams of retaliation and curses! Of course this just made the visitors laugh all the more as they stood a safe distance away from the end of the chains or steel bars.

"John Monro was without question one of the most famous mad-doctors of his generation. Besides his position at Bethlem Hospital, he was also a major figure in the emerging private "trade in lunacy" that was so notable a feature of eighteenth-century England's burgeoning consumer society. Monro attended Bethlem at a time when the hospital's custom of exposing the insane to the eyes of sightseers reached its apogee. In the last years of his tenure as its physician, the practice was radically curtailed—though not at his initiative—after a wave of public, literary, and media protest. Recognized by contemporaries as a leading authority on insanity, Monro's close social connections with members of the aristocracy and gentry, as well as with medical professionals, politicians, and divines, ensured for him a significant place in the social, political, cultural, and intellectual world of his time." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xiv)

"The eighteenth century was in two minds about madness, fearful of its power, its suddenness, its inaccessibility, yet obsessed with its manifestations, its proximity, its apparently mischievous aping of sane behaviour, of sane patterns of thought. The massively impressive walls of Bethlem Hospital in Moorfields, London, signified the secure placement in the public mind of insanity in its various manifestations, just as Caius Gabriel Libber's giant statues of 'Melancholy Madness' and 'Raving Madness' that stood at the gates marked down sure patterns of diagnosis and representation. But Bethlem was also a spectacle, a place of entertainment. Its walls relented for the modest price of admission." (Patterns of Madness in the Eighteenth Century, A Reader, Allan Ingram, 1998 AD, p 2)

"This was a time, moreover, when Bethlem was to reach perhaps the height of its exposure to the prying eyes of the public. It had long been the custom of its governors to permit outsiders a rather indiscriminate access and license as visitors to come and gaze at the insane. Yet it was in the 176os that the quantity of visitors appears to have reached its peak, as the hospital acquired an ever greater popularity as a source of public entertainment. (This was certainly the decade when annual poor's box takings from the donations made by those viewing the hospital were at their highest, providing one telling measure of the mounting volume of visitation.) Bedlam's wards had become emblematic of Unreason, its very name synonymous with lunacy, and its crazed inmates reduced to a spectacle to which the masses reacted with mirth, mockery, and callous teasing. As one observer recorded after mid-century, "... a hundred people at least [were] . . . suffered unattended to run rioting up and down the wards, making sport and diversion of the miserable inhabitants [some of whom were] provoked by the insults of this holiday mob into furies of rage; [prompting in] the spectators . . . a loud laugh of triumph at the ravings they had occasioned."" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 21)

"Yet just as more and more hoi polloi [rabble, riffraff, the common people] were coming to gawk or to laugh at, to pity or to receive moral instruction and edification from a sight of the lunatics," more and more of those moving in influential, educated circles were beginning to raise their voices in protest. As the expression of painful sensibilities grew more legitimate, in what historians and literary critics have evocatively termed a new "age of sensibility," men and women "of feeling" gave vent to much ingenuous (and disingenuous) sorrow, mortification, and disgust over the spectacle of lunatics being shown like animals in a human zoo. The fun of seeing the insane began to pale and recede. Visiting Bethlem became one of a number of evocative symbols of barbarous insensibility and vulgar showiness, alongside public executions, public dissections, grandiloquent charity, and grandiose forms of burial." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 21)

William Battie refused to allow this at St. Luke's and even protested that it made the mad, even more mad.

Eventually laws were passed that outlawed this evil practice: "The committee's findings (a second report was published in 1816) marked a turning-point in attitudes towards treatment of madness, even though no legislation followed for 13 years. Public opinion, that had once happily looked on madness as a spectator sport, swung decisively behind regulation and reform." (Patterns of Madness in the Eighteenth Century, A Reader, Allan Ingram, 1998 AD, p246)

In a bizarre twist. at the same time Monro was allowing the mad to be mocked, preachers and Christianity were seen as a cause of mental illness. In fact they were even barred from entering mad houses: "Through its emphasis on sin and the spirit world, on hellfire and damnation, it was said to be actually driving its adherents into madness." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 80)

I must acknowledge that Gallant Structure of New Bethlam to be one of the Prime Ornaments of the City of London, and a Noble Monument of Charity, so I would with all Humility beg the Honorable and worthy Governours thereof, that they would be pleased to use some Effectual means, for restraining their inferior Officers, from admitting such Swarms of People, of all Ages and Degrees, for only a little paltry Profit to come in there, and with their noise, and vain questions to disturb the poor Souls; as especially such, as do Resort thither on Holy-dayes, and such spare time, when for several hours (almost all day long) they can never be at any quiet, for those importunate Visitants, whence manifold great inconveniences do arise. For, First, Tis a very Undecent, Inhumane thing to make, as it were, a Show of those Unhappy Objects of Charity committed to their Care, (by exposing them, and naked too perhapes of either Sexs) to the Idle Curiosity of every vain Boy, petulant Wench, or Drunken Companion, going along from one Apartment to the other, and Crying out; This Woman is in for Love; That Man for Jealousie. He has Over-studied himself, and the Like. Secondly, This staring Rabble seldom fail of asking more then an hundred impertinent Questions. — As, what are you here for ? How Long have you been here, &c. which most times enrages the Distracted person, tho calm and quiet before, and then the poor Creature falls a Raving .. Thirdly, As long as such Disturbances are suffered, there is little Hope that any Cure or Medicine should do them good to reduce them to their Senses or right Minds, as we call it, and so the very Principle end of the House is defeated. Certainly the most hopeful means towards their Recovery would be to keep them with a Clean Spare Diet, and as quiet as may be, and to let none come at them but their particular Friends, Grave sober People and such as they have a kindness for, and those to, not alwayes, but only at proper times, whereby discoursing with them in their Lused Intervals Gravely, Soberly, and Discreetly, and humouring them in little things, shall do much more, I am Consident, toward their Cure, then most of the Medicines that are commonly Administred. (A treatise of dreams & visions, Thomas Tryon, 1695 AD)

C. Prison for social control!

Mad houses were most certainly jails for social control of people who did not fit in or were targets of retaliation. If you had the money, you could get anybody committed to a mental hospital, including a nagging wife!

The solution to "street people" in the 1750's was to round them all up and cast them into the mental hospital! These people we not mad, just poor.

Even a practicing surgeon, Mr. Crowther, who was obviously an alcoholic, chose on his own free will to live in Bedlam. He was content to make this place his home at night, while he performed surgery at the nearby hospital during the day! This may seem bizarre, but it happened! Everyone know who he was and where he lived and worked!

Alexander Cruden is an example of a good Christian who was falsely committed for condemning (like John the Baptist) the sin and adultery of public officials!

"I think it is a very hard case for a man to be locked up in an asylum and kept there; you may call it anything you like, but it is a prison." (Sir James Coxe, testimony before the House of Commons Select Committee on the Operations of the Lunacy Laws, 1877)

"their nakedness and their mode of confinement, gave this room the complete appearance of a dog-kennel." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of A. Mr. E. Wakefield)

"At Leskeard there were two women confined. In a fit place for them? Very far from it; indeed I hardly know what to term the places, but they were no better than dungeons." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of Henry Alexander, Esq.)

"William Belcher, a patient incarcerated for seventeen years in a Hackney madhouse, and freed only after the intervention of John Monro's son Thomas, referred to the institution in which he had been locked away as a "premature coffin of the mind," or "one of the graves of mind, body, and estate," confinement for him being experienced as a form of "legal death." Belcher was far from the first or only contemporary to perceive (or to be represented as conceiving) confinement in a madhouse as a form of living death. Some lunatics were indeed confined for life, and literary accounts of patients such as Margaret Nicholson dwelt morbidly on the departure of their hopes and spirit as they whiled away their days at Bethlem and kindred institutions. Other patients, meanwhile, were artistically represented sketching gravestones on their cell walls to signify their ineluctable entombment in the madhouse or the lunatic hospital" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xvi)

"Undertakers, of course, offered (and offer) a particular and peculiar sort of assistance to others, taking on the essential, but rather unpopular, work of arranging for the handling of the corpse, the conduct of a funeral, and the interment of the body. Mad-doctors undertook the similarly burdensome and unpleasant (but increasingly necessary) task of treating, coping with, and confining difficult or impossible people. Madness, moreover, was widely portrayed as entailing a kind of social, mental, or metaphysical death, and from this perspective, mad-doctoring might be thought of as an onerous undertaking, one that was intimately associated with concerns about the corruption and death of the mind." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p xix)

"The steward's accounts (which, for example, record purchases such as "4 Doz[e]n of Men & Womens Leg Locks" at £6 6s., in 1765,108 and a further dozen leg locks and an extra dozen handcuffs less than two years later), suggest the pervasive extent of mechanical restraint at Bethlem. It was the apothecary (1772-95) John Gozna (d. 1795), rather than Monro, who appears to have introduced strait waistcoats into the hospital very soon after his appointment, in preference to chains, although the latter were never fully dispensed with." Nonetheless, this was an age before the fashionable nineteenth-century doctrine of non-restraint had been heard of, and it would be anachronistic to criticize Monro or any others at Bethlem too harshly for the apparent lack of interest they took in methods that were relatively universally employed in the treatment of the insane, at least before John Monro's death in the 1790s-techniques that these practitioners must have regarded as pragmatic and essential tools for the control and disciplining of unruly patients." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 33)

Wives were wrongly committed to mad houses by their husbands: "The mid-eighteenth century saw a torrent of criticism of the unregulated state of private madhouses, fed by scandalous tales of alleged false confinement and intermittent, but influential, appeals for legislative intervention-all of which were met initially with official indifference. Eventually, however, the rising tide of complaints of corruption, cruelty, and malfeasance in the mad-trade provoked some feeble and flickering interest in parliament, and both Monro and Battie found themselves called upon to testify in the brief inquiry that was finally launched in 1763. The proceedings were cursory in the extreme, only four cases of alleged false confinement being considered, only two madhouses (Miles's at Hoxton, and Turlington's at Chelsea) being inquired into, and only eleven witnesses being named as having been summoned." They culminated in a printed report of just eleven pages, even though the limited testimony that was taken seemed calculated to raise rather than mitigate public anxieties. Each case involved women (namely, Mrs. Hester Williams, Mrs. Hawley, Mrs. Smith, and Mrs. Durant) who had allegedly been falsely confined by their husbands and other family members (adding ballast to Foyster's arguments about the manipulable role of the madhouse in marital disagreements), and in three of these cases there was clear evidence of abuse, with only one woman seeming to have been insane. Witnesses stressed the employment of ruses and trickery to initiate and perpetuate these confinements, and the obstruction of contact with the outside world, in particular through being locked up and mechanically restrained night and day, having visitors refused and correspondence barred, and being "treated with Severity" by keepers." The women themselves complained that they received no medicines or medical treatment whatsoever and were never even attended by a medical practitioner, or not, at least, until a habeas corpus was effected." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 155)

Alexander Cruden is an example of a good Christian who was falsely committed for condemning (like John the Baptist) the sin and adultery of public officials! Basically, he was sent to the mad house for being a public irritant... to those in charge!

Mr. Crowther: The alcoholic practicing surgeon who lived in the mad house for 10 years on his own free will! He was content to make this place his home at night, while he performed surgery at the nearby hospital during the day! This may seem bizarre, but it happened! Everyone know who he was and where he lived and worked! "Do you remember the case about which Mr. Crowther, who was the surgeon of the Hospital, made some observations as to the cause of his death? I do. Do you know what those observations were? Knowing the situation of Mr. Crowther at that time, I paid no attention to it. Mr. Crowther was generally insane and mostly drunk. He was so insane as to have a strait-waistcoat. What situation did Mr. Crowther hold in the Hospital? Surgeon. How long had he been so? I do not know; he was surgeon when I came there. How long did he continue so, after he was in a situation to be generally insane and mostly drunk? I think the period of his insanity was about 10 years ago. And the period of his drunkenness? He always took too much wine. How long is it since he died? Perhaps a month ago. Then for ten years, Mr. Crowther was surgeon to the hospital: During those ten years he was generally insane; he had had a strait-wasitcoat, and was mostly drunk? He was. And during that period he was continued as surgeon to the hospital? He was. Did he attend the patients? Yes, he did. Did he attend the patients as surgeon? Yes, till a week before his death; from his incapacity to officiate as surgeon, he frequently brought some medical professional man to attend. But he did sometimes attend himself without assistance? Certainly, he did. Were the governors of the Hospital acquainted with the fact of his incapacity? I should think not. His insanity was confined principally to the abuse of his best friends; he was so insane, that his hand was not obedient to his will." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of John Haslam)

Sane women cast into Bedlam: "Have you visited Bethlem? I have, frequently; I first visited Bethlem on the 25th of April 1814. What observations did you make? At this first visit, attended by the steward of the Hospital and likewise by a female keeper, we first proceeded to visit the women's galleries: one of the side rooms contained about ten patients, each chained by one arm or leg to the wall; the chain allowing them merely to stand up by the bench or form fixed to the wall, or to sit down on it. The nakedness of each patient was covered by a blanket-gown only; the blanket-gown is a blanket formed something like a dressing-gown, with nothing to fasten it with in front; this constitutes the whole covering; the feet even were naked. One female in this side room, thus chained, was an object remarkably striking; she mentioned her maiden and married names, and stated that she had been a teacher of languages; the keepers described her as a very accomplished lady, mistress of many languages, and corroborated her account of herself. The Committee can hardly imagine a human being in a more degraded and brutalizing situation than that in which I found this female, who held a coherent conversation with us, and was of course fully sensible of the mental and bodily condition of those wretched beings, who, equally without clothing, were closely chained to the same wall with herself. ... Many of these unfortunate women were locked up in their cells, naked and chained on straw, with only one blanket for a covering." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of A. Mr. E. Wakefield)

Vagrant poor were taken off the streets: Here is a vagrant and very sane normal man who was able to read books and the daily newspaper and have an intelligent conversation with government legislators: "In one of the cells on the lower gallery [at Beldam] we saw William Norris; he stated himself to be 55 years of age, and that he had been confined about 14 years; that in consequence of attempting to defend himself from what he conceived the improper treatment of his keeper, he was fastened by a long chain, which passing through a partition, enabled the keeper by going into the next cell, to draw him close to the wall at pleasure; that to prevent this, Norris muffled the chain with straw, so as to hinder its passing through the wall; that he afterwards was confined in the manner we saw him, namely, a stout iron ring was rivetted round his neck, from which a short chain passed to a ring made to slide upwards or downwards on an upright massive iron bar, more than six feet high, inserted into the wall. Round his body a strong iron bar about two inches wide was rivetted; on each side of the bar was a circular projection, which being fashioned to and inclosing each of his arms, pinioned them close to his sides. This waist bar was secured by two similar bars which, passing over his shoulders, were rivetted to the waist bar both before and behind. The iron ring round his neck was connected to the bars on his shoulders, by a double link. From each of these bars another short chain passed to the ring on the upright iron bar. We were informed he was able to raise himself, so as to stand against the wall, on the pillow of his bed in the trough bed in which he lay; but it is impossible for him to advance from the wall in which the iron bar is soldered, on account of the shortness of his chains, which were only twelve inches long. It was, I conceive, equally out of his power to repose in any other position than on his back, the projections which on each side of the waist bar enclosed his arms, rendering it impossible for him to lie on his side, even if the length of the chains from his neck and shoulders would permit it. His right leg was chained to the trough; in which he had remained thus encaged and chained more than twelve years. To prove the unnecessary restraint inflicted on this unfortunate man, he informed us that he had for some years been able to withdraw his arms from the manacles which encompassed them. He then withdrew one of them, and observing an expression of surprise, he said, that when his arms were withdrawn he was compelled to rest them on the edges of the circular projections, which was more painful than keeping them within. His position, we were informed, was mostly lying down, and that as it was inconvenient to raise himself and stand upright, he very seldom did so; that he read a great deal of books of all kinds, history, lives or anything that the keepers could get him; the newspaper every day, and conversed perfectly coherent on the passing topics and the events of the war, in which he felt particular interest. On each day that we saw him he discoursed coolly, and gave rational and deliberate answers to the different questions put to him. The whole of this statement relative to William Norris was confirmed by the keepers." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of A. Mr. E. Wakefield)

Vagrant poor were taken off the streets: "Will you be so good as to state to the Committee any other house you visited? The next I have to mention, is at Leskeard in Cornwall .... At Leskeard there were two women confined. In a fit place for them? Very far from it; indeed I hardly know what to term the places, but they were no better than dungeons. Were they under ground? No, they were buildings, but they were very damp and very low. In one of them there was no light admitted through the door; neither light nor air. Both of them were chained down to the damp stone-floor, and one of them had only a little dirty straw, which appeared to have been there for many weeks. No bed-place at all, but sleeping on the stone-floor to which she was chained? Yes; the chain was a long one, and fastened to the centre, and admitted of her just coming outside, where she sat. Was she violent? By no means, she was perfectly quiet and harmless. I would just mention her case: We felt much interested in her situation, and we enquired the reason of her confinement of the mistress of the workhouse; and it appeared she had been confined many months, both winter and summer; and the only cause they assigned was, that she was troublesome; they could not keep her within; she was roving about the country, and they had had complaints lodged against her from different persons." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of Henry Alexander, Esq.)

D. Preachers and Christianity caused madness!

In a bizarre twist. at the same time Monro was allowing the mad to be mocked, preachers and Christianity were seen as a cause of mental illness. In fact they were even barred from entering mad houses: "Through its emphasis on sin and the spirit world, on hellfire and damnation, it was said to be actually driving its adherents into madness." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 80)

"For James [Monro], the profession of such beliefs was itself a clear sign of mental disturbance, and he promptly informed Robert Wightman, the Edinburgh merchant who was responsible for Cruden's confinement, "that the Prisoner was a Man of Sense and Learning, and of a good Education, but that he was a great Enthusiast; and he believed that he thought that God would send an Angel from Heaven, or would work some Miracle for his Deliverance."" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 98

"In all probability, John Monro shared the traditional hostility of Bridewell and Bethlem's largely Anglican board of governors to sectarian religions, the Methodists in particular. It must be said, however, that most of the available evidence on this point appears to derive from the period of James's physicianship rather than John's. For example, attempting to visit Joseph Periam and other Methodist patients in Bethlem during the second quarter of the century, George Whitefield (1714-70) and John Wesley (1703-91) both complained that they were refused entry. According to Wesley, recalling an interrupted visit of a year or so be-fore John's election as joint physician, it had been decreed that "none of these preachers were to come there" (although there is no trace of such an order in Bethlem's records). Wesley was repeatedly to censure Bethlem's medical regime in print-for this and other reasons-and here he laid on the sardonic irony with a trowel, alleging that the prohibition on allowing him in was "for fear of making them [the patients] mad."" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 32)

"Methodism was pilloried by its critics throughout this period for its alleged encouragement of "unseemly" forms of worship, spiritual transports, and morbidly pious, agonizing behavior that was often dismissed as "methodical madness," tending toward the incitement of civil and mental unrest."' While Wesley and Whitefield loudly proclaimed that Periam was sane, and had merely been suffering from a spiritual crisis, they castigated James Monro and his colleagues for giving him purges and vomits when what he needed was counsel and guidance." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 81)

E. Laws passed regarding committal to Bedlam:

The abuses were being noticed and legislators in the British house of parliament began to draft private members bills to be passed into law.

At first it was proposed that a person could not be committed to a man house unless witnessed with the written consent of: the person's local preacher, 12 neighbors and two doctors. It also proposed that each person be visited by their own minister and a justice of the peace at least once every 14 days.

What ended up happening is that ministers were considered mentally ill themselves, since they believe in God, and were not only excluded from the process of committing a person to a mental hospital, they were barred from even entering the mad houses! Psychiatry has had a long history of being viciously anti-Christian!

"The author appealed for legislation requiring that no confinement take place without an attestation in writing from the patient's parish minister and twelve of his neighbors and a certificate of two physicians, "neither of them concerned in any such house." He also recommended severe penalties for an improper confinement: a fine of £50 for any convicted madhouse master or keeper, plus imprisonment for at least three years in a county gaol [jail]. Additionally, he urged that madhouse servants and keepers be encouraged to inform on their masters by the enticement of a £10 fine payable to them for reporting such cases. (The master himself was to have the [rather minimal] protection of a right of appeal to the King's Bench, though the act that was finally passed offered no protection whatsoever.) Concluding, the author of this grand scheme urged that each house should be visited by the local parish clergyman and JP at least once a fortnight [every 14 days], with the inspectors guaranteed complete freedom of access.'" ... Two years later (1774), the Act for Regulating Madhouses (14 George III c. 49) was finally passed. Perhaps, as Porter has suggested, the prolonged delay in enacting legislation should be seen as a function of the opposition of the College of Physicians, some of whose members "had a large financial stake in metropolitan madhouses." If so, it is somewhat ironic that parliament handed over the power to license and inspect madhouses in the metropolis to the College. (In the provinces, similar authority was granted to local magistrates.) There were other signs, too, that medical men had successfully lobbied behind the scenes to protect their interests: the 1772 appeal notwithstanding, commitment under the new act required only a single medical certificate, and local clergymen were firmly excluded from any officially sanctioned role in the process." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 159)

"Through its [religions] emphasis on sin and the spirit world, on hellfire and damnation, it was said to be actually driving its adherents into madness." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 80)

F. Treatments and Conditions in Bedlam:

|

|

This is a drawing from a novel that is considered an accurate account of the inside of Bedlam. We have labeled each of the people in the drawing which were considered representative of the kinds of people who were insane. Of course this drawing leaves out the fact that many in Bedlam were not insane, but were rounded up as vagrant street people or targets of false imprisonment by others who paid the keepers bribe money!

(Click on image to enlarge) |

- "HOW TO TREAT A BEDLAMITE: It may well be that, rather than his complicity in putting the inmates on display, what most indicts Monro's record at Bethlem is something else: the singularly unadventurous approach toward the treatment of patients that he and other medical officers continued to practice there for decades. Therapeutics at Bethlem was characterized by relatively uniform purges, vomits, and bleeding, administered seasonally to patients, with the occasional addition of tonics (such as alcohol), cold bathing (or other cooling applications), and warm or hot baths, all of these "heroic" interventions being supplemented by (a mostly "lowering" form of) diet and regimen. This model, whereby repletion in the system was countered by depletion, and vice versa, was founded on an essentially humoral approach to mental diseases. Overlaid since the late seventeenth century by a new, mechanistic brand of Newtonian science, older principles and even types of treatment had in reality changed remarkably little. To be sure, John Monro was skeptical of some conventional treatments: he objected to blistering, for example. This was a form of "counter-irritation" involving the application of a chemical preparation to draw out a blister on the head, neck, shoulder, foot, or some other exposed part of the body, normally recommended to draw the peccant fluids and humors to the body's surface." (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 28)

- "The surgeon informs us, that " The curable patients in Bethlem Hospital, are regularly bled about the commencement of June, and the latter end of July:" and the apothecary to the same Institution tells us ; " It has been for many years the practice, to administer to the curable patients, four or five emetics in the spring of the year." He adds, " but on consulting my book of cases, I have me found that such patients have been particularly benefited by the use of this remedy." It appears that this indiscriminate treatment of insanity, is not confined to Bethlem Hospital." (Description Of The Retreat For Insane, Samuel Tuke, 1813 AD)

- "Both doctors prescribed similar doses of purges, vomits, and bleeding, and Cruden alleged that both doctors dosed and bled him routinely and excessively, the bleeding James ordered from his foot leaving it "for some months after benumn'd," and John once ordering twelve ounces of blood to be taken. Both Monros were also attacked as the prime representatives of a profession that Cruden had little respect for. The Corrector queried in 1739: ". . . is there so great Merit and Dexterity in being a mad Doctor? The common Prescriptions of a Bethlemetical Doctor are a Purge and a Vomit and a Purge over again, and sometimes Bleeding, which is no great Mystery." And in 1754 he [Cruden] similarly observed: . . . tho' a person be not a conjuror he may set up to be a mad-doctor, the chief prescriptions being bleeding, purging, vomiting, and sometimes bathing: And if these are not effectual . . . the patient is incurable. . . . What is Dr. Monro? A mad-doctor; and pray what great matter is that? What can mad-doctors do? prescribe purging physic, letting of blood, a vomit, cold bath, and a regular diet? How many incurables are there? ... physicians . are often poor helps; and if they mistake the distemper, which is not seldom the case, they do a deal of mischief.'" (Undertaker of the mind: John Monro, Jonathan Andrews, Andrew Scull, 2001 AD, p 108)

- "In the men's wing [at Bedlam] in the side room, six patients were chained close to the wall, five handcuffed, and one locked to the wall by the right arm as well as by the right leg; he was very noisy; all were naked, except as to the blanket gown or a small rug on the shoulders, and without shoes; one complained much of the coldness of his feet; one of us felt them, they were very cold. The patients in this room, except the noisy one, and the poor lad with cold feet, who was lucid when we saw him, were dreadful idiots; their nakedness and their mode of confinement, gave this room the complete appearance of a dog-kennel." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of A. Mr. E. Wakefield)

- "Whilst looking at some of the bed-lying patients [at Bedlam], a man arose naked from his bed, and had deliberately and quietly walked a few paces from his cell door along the gallery; he was instantly seized by the keepers, thrown into his bed, and leg-locked, without enquiry or observation: chains are universally substituted for the strait-waistcoat. In the men's wing were about 75 or 76 patients, with two keepers and an assistant, and about the same number of patients on the women's side; the patients were in no way distinguished from each other as to disease, than as those who are not walking about or chained in the side rooms, were lying stark naked upon straw on their bedsteads, each in a separate cell, with a single blanket or rug, in which the patient usually lay huddled up, as if impatient of cold, and generally chained to the bed-place in the shape of a trough; about one-fifth were in this state, or chained in the side rooms." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of A. Mr. E. Wakefield)

- Here is a woman who suffered depression after her fiancée married another woman

! "With respect to this woman whom you found chained to the floor, you probably were led into conversation with her; did she tell you the wants she felt there? Not at all, she appeared incapable, the mind appeared gone very much; she was about thirty years of age; and it appeared, I think, that about seven years before she was a very respectable maid-servant, who lived in various reputable families there, and was about to be married to a young man who left Leskeard and went to reside at Plymouth Dock, and not hearing from him, she went over, and found he was about to be married the next day to another person, and it had such an effect upon her mind that she has been deranged ever since. A friend was with me, who, though not professionally a medical man, has attended a good deal to the wants of his poor neighbours about him, and he had no doubt at all she might have been restored if proper means had been used. Did she appear in a bad state of health, independent of the loss of reason? She was extremely dejected and very much emaciated, but I attributed it to not having sufficient nutriment. We examined the provision, which was very poor. She was not allowed water to wash herself? No. Did you ask, whether she had enough to drink of water? We did not ask that question; we put it as a question, whether she had water or not; and they said, No, she made no use of it: The other woman was confined in the same manner on the stone-floor chained; but there was a window in the cell, and she had a bed that I think rested upon the floor, I do not think there was any bedstead: She kept the place particularly neat; her greatest complaint was that she had nothing to do; but she shewed us several places in her arms, which she said arose from the children throwing stones at her, which they were allowed to do, and insult her very much. The children in the house? Yes." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of Henry Alexander, Esq.)

- "Another house I visited, was at Tavistock: With regard to that, I am sorry my information will not be altogether satisfactory, as we did not see the Insane poor themselves: We went to visit the house, in which sixty poor persons were confined; and after going through the house, the situation of which was dreadful, indeed I could not stand up at all in some of the lower rooms; the rooms were very small, and in one of the bed-rooms, seventeen people slept; one man and his wife slept in the room with fifteen other people." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of Henry Alexander, Esq.)

- "Were there any Insane persons in that workhouse [Tavistock]? There were three which we were not permitted to see: We enquired if there were any Insane persons; and upon expressing a desire to see them, we were at first refused, on the ground that the place was not fit for us to go into; but we persisted in our intreaties to see them, and went up the yard, where we understood the cells were, and upon entering them, we found that the inmates had been removed; there were three of them. They had been removed out? They had been removed out that morning. For what purpose? The cells had been washed and cleaned out. Who refused you? The master of the house. He did it not in a peremptory manner at all, but told us it was unfit for us to go, and indeed we found it so. What was the state of the cells? I never smelt such a stench in my life, and it was so bad, that a friend who went with me said he could not enter the other. After having entered one, I said, I would go into the other; that if they could survive there the night through, I could at least inspect them. There were three cells? Yes: The cells themselves were not small; there were bedsteads which were completely rotten with filth; they were more like handbarrows. Were there any bed-clothes?--There were none at that time. I think there was straw, but no bed-clothes; I cannot say that they never had any bed-clothes. At what season of the year did this visit take place? I think it was in July; the latter end of June or the beginning of July in the year 1813. The stench was so great I felt almost suffocated; and, for hours after, if I ate any thing, I still retained the same smell; I could not get rid of it; and it should be remembered that these cells had been washed out that morning, and the doors had been opened some hours previous. Did they know you were coming there? No, they did not at all know it; we generally took care to see them as they were. There was no window, but a small hole cut in the door. I really do not believe I could have survived an hour, scarcely, in one of those places; it was a most suffocating dreadful smell." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of Henry Alexander, Esq.)

- Sexual assault by the male "Keepers":

"Do you remember a keeper of the name of King, at Bethlem, who is now at Liverpool? Perfectly. Was not he employed as keeper of the female patients at Bethlem? He was occasionally. Was not King, when keeper of the female patients, charged by Mr. Till, the manager of the London waterworks, with being too familiar with a female patient of great beauty, such female having been a servant of Mr. Till? I do not know that he was charged by Mr. Till with too great familiarity, but the patient herself did charge him with that. He being the keeper of the female patients at that time? Yes; she complained to me of it. What was the result of that investigation? There was great asseveration on one side, and denial of it on the other; I do not know whether we got at the truth. Was not the regulation immediately made by the governors, for not again employing men as keepers of women? They had endeavoured to do that long before, upon another business. Did not the governors, from learning that fact, direct that no man should again be put as keeper of the women? I do not recollect that they came to any resolution upon that case; it was about three years ago." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of John Haslam)

- Sexual assault by the male "Keepers":

"Some years ago, a female patient had been impregnated twice, during the time she was in the Hospital; at one time she miscarried; and the person who was proved to have had connexion with her, being a keeper, was accordingly discharged." (Report From The Committee On Madhouses In England, 1815 AD, Testimony of John Haslam)

- "With regard to the beds, I think there is great mismanagement, there are beds which frequently get wetted; those flocks are taken into an upper room, emptied out of the ticks, the ticks washed and mended, but the flocks never thoroughly dried, so that when they are put again in the ticks they are still damp and of course very dangerous for any person to sleep on, though I believe that every clean patient on going into the house is allowed a new bed. I myself had a damp bed given me which I laid on for some time, and fear I shall feel the effects of it through my future life, as I have for some months past been subject to a pain in my loins, which I never had before." (The Interior Of Bethlem Hospital, Urbane Metcalf, 1818 AD)

- "The blood of maniacs is sometimes so lavishly spilled, and with so little discernment, as to render it doubtful whether the patient or his physician has the best claim to the appellation of a madman. This reflection naturally suggests itself upon seeing many a victim of medical presumption, reduced by the depleting system of treatment to a state of extreme debility or absolute idiotism. At the same time, I do not wish to be understood as altogether proscribing the use of the lancet in this formidable disorder. My intention is solely to deprecate its abuse. (A Treatise on Insanity, Philippe Pinel, 1806 AD)

- 1818 AD, Urbane Metcalf, a Patient at Bedlam, gives a shocking first hand account of what it was like to be "treated" for insanity at Bedlam. He was a patient before and after Parlament fired the staff at Bedlam in 1815 AD because he had reported how a keeper named Blackburn murdered a patient named fowler: "Fowler, who one morning was put in the bath by Blackburn, who ordered a patient then bathing, to hold him down, he did so, and the consequence was the death of Fowler, and though this was known to the then officers it was hushed up; shameful". He describes a keeper named Davis as a, "cruel, unjust and drunken man, and for many years as keeper secretly practised the greatest cruelties to those under his care". He described another keeper named Rodbird, that he is as "an idle, skulking, pilfering scoundrel". He describes how the butcher stole from the patients their portion of food for personal gain: "Mr. Vickery the cutter [butcher], has it in his power to defraud the patients in many instances...". Metcalf stands as the final witness that helped forever change the kinds of brutal physical torture and neglect that existed in the largest English insane asylums for over 100 years. (The Interior Of Bethlem Hospital, Urbane Metcalf, 1818 AD)

- Death from Gangrene Rampant

: "Under the head " Medical Treatment," as practiced in the Retreat, some may possibly inquire, what are the means employed in mortifications, arising from cold and confinement ? " a calamity, which," says a writer before alluded to, " frequently happens to the helpless insane, and to bed-ridden patients ; as my attendance in a large work-house, in private mad-houses, and Bethlem Hospital, can amply testify." Haslam also observes, that the patients in Bethlem Hospital, " are particularly subject to mortification's of the feet ; and this fact is so well established from former accidents, that there is an express order of the house, that every patient, under strict confinement, shall have his feet examined every morning and evening in the cold weather, by the keeper, and also have them constantly wrapped in flannel ; and those who are permitted to go about, are always to be found as near to the fire as they can get, during the winter season." Dr. Pinel also confesses, that " seldom has a whole year elapsed, during which no fatal accident has taken place, in the Hospital de Bicetre, (in France,) from the action of cold upon the extremities." Happily, in the Institution I am now describing, this calamity is hardly known ; and no instance of mortification has occurred, in which it has been, in any degree, connected with cold or confinement. Indeed, the patients are never found to require such a degree of restraint, as to prevent the use of considerable exercise, or to render it at all necessary to keep their feet wrapped in flannel." (Description Of The Retreat For Insane, Samuel Tuke, 1813 AD)

By Steve Rudd:

Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Send us your story about your experience with modern Psychiatry

Go To Start: WWW.BIBLE.CA

![]() See also: History of Psychiatry homepage

See also: History of Psychiatry homepage