![]() See also: History of Psychiatry homepage

See also: History of Psychiatry homepage

Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting

|

|

Introduction:

Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting, Sir Charles Bell, 1806 AD

PREFACE.

Anatomy stands related to the arts of design, as the grammar of that language in which they address us. The expressions, attitudes, and movements of the human figure, are the characters of this language ; which is adapted to convey the effect of historical narration, as well as to show the working of human passion, and give the most striking and lively indications of intellectual power and energy. The art of the painter, considered with a view to these interesting representations, assumes a high character. All the lesser embellishments and minuteness of representation are, by an artist who has those more enlarged views of his profession, regarded as foreign to the main subject: distracting and hurtful to the grand effect, admired only because they have the merit of being accurate imitations, and almost appear to be what they are not. This distinction must be felt, or we shall never see the grand style in painting revived. The painter must not be satisfied to copy and represent what he sees; he must cultivate this talent of imitation, merely as bestowing those facilities which are to give scope to the exertions of his genius, as the instruments and means only which he is to employ for communicating his thoughts, and presenting to others the creations of his fancy. It is by his creative powers alone that he can become truly a painter; and for these he is to trust to original genius, cultivated and enriched by a constant observation of nature. Till he has acquired a poet's eye for nature, and can seize with intuitive quickness the appearances of passion, and all the effects produced upon the body by the operations of the mind, he has not raised himself above the mechanism of his art, nor does he rank with the poet or the historian.

To assist the painter in a department of this inspiring study, is one of the Author's objects in these Essays. He has been desirous, in principles deduced from the structure of man, and the comparative anatomy of animals, to lay a foundation for studying the influence of the mind upon the body; and he ventures to expect great indulgence to an attempt at once so new and so difficult, where there is no authority to consult but that of nature.

After the first edition was published, I was so fortunate as to make discoveries in the Nervous System, which gave a new and extraordinary interest to the subject of these essays. I found that there was a system of nerves, distinguishable by structure and endowments, which had hitherto been confounded with the common nerves; and having traced them through the face, and neck, and body, and compared them in the different classes of animals, it was finally discovered that these nerves were the sole agents in expression, when the frame was wrought under the influence of passion.

Here was secure ground on which to proceed ; before this, but vague surmises could be entertained of the nature of expression, since the organs had not been ascertained, or only partially. We witnessed emotions, we felt the sympathies implanted in our nature, nevertheless the description of passion was a mere description; poetical it might be, but never philosophical, since it was not known by what links the organs were excited, nor by what course the influence of the mind was propagated to the muscular frame. We might study to be accurate and minute, but something was wanting, and the inquirer was thrown back dissatisfied.

In proof of this I take the following extract from Dr. James Beattie. (Dissertations, Moral and Critical, p. 242)

"Descartes, and some other philosophers, have endeavoured to explain the physical cause which connects a human passion with its correspondent natural sign. They wanted to show, from the principles of motion, and of the animal economy, why fear, for example, produces trembling and paleness; why laughter attends the perception of incongruity; why anger inflames the blood, contracts the brows, and distends the nostrils; why shame is accompanied with blushing; why despair fixes the teeth together, distorts the joints, and disfigures the features; why scorn shoots out the lip; why sorrow overflows at the eyes ; why envy and jealousy look askance ; and why admiration raises the eyebrows and opens the mouth. Such inquiries may give rise to ingenious observation, but are not in other respects useful, because never attended with success. He who established the union of soul and body knows how and by what intermediate instruments the one operates upon the other. But to man this is a mystery unsearchable. We can only say that tears accompany sorrow, and the other natural signs their respective passions and sentiments, because such is the will of our Creator, and the law of the human constitution.

"Yes, if that will be declared, we must abide by it and search no further. But, on the other hand, something informs me that it is acceptable to exercise the talents bestowed upon us, and to search and explain the Creator's works. This divine and philosopher says well, if we are to look on the surface only. But where is his authority for going no deeper? No doubt he believed that he was giving a very accurate statement of the effects of passion, but it would be easy to show that he has jumbled signs, quite incongruous, from an ignorance of their natural relations. We have in this extract an enumeration of phenomena the most surprising in the whole extent of nature, and the most affecting to human sympathies. We must confess that they are so deeply implanted in our nature, that we shall not be able to discover the ultimate connexion between the emotions of the soul and those signs of the body. But this conviction should not extinguish the desire of comprehending the organs of expression, more than those of the voice, or of seeing and hearing.

In these Essays the subject matter does not always correspond with the titles, so although there be something said of the forms of beauty, and the expression in painting, the work has a larger scope, and aims at greater usefulness. It has been the author's main design to furnish a sufficient foundation for arranging the symptoms of disease, and for a more accurate description of them.

The description of a disease is a mere catalogue of signs, if their cause and relation be not understood; and' if no cause for certain appearances, and no relation among them be observed, the signs can neither be accurately recorded nor remembered.

The motion of one part of the body, produced by the excitement of another, and the movements produced by passion on the frame of the body, become symptoms when caused by disease.

A man pulling on a rope draws his breath and retains it, to give force to his arms. Instinct produces the same effect in fear, for the moment of alarm is marked by a sudden inspiration, and a state of preparation for action. This, the painter requires to know before he can give an accurate representation of these conditions of the frame. But it is even more important to the physician. In the asthmatic, for example, the chest is kept distended, and the whole attitude is that best calculated to aid the actions of the muscles of respiration; and so that attitude and these actions become symptomatic of the disease.

And can there be a better lesson whereby symptoms are to be learned, than in the observation of the natural sympathies and appearances presented when the frame is wrought upon by the sentiments of the mind ? An uninformed person walks through the wards of an hospital with a sensation varying only in intensity, but the physician sees a thousand features of disease to which he is blind, and suffers hopes and fears to which he is a stranger. The physician sees but a part, yet that partial view is attended with a train of consequences which none can perceive but those who are acquainted with the secret ties which bind the parts together.

It is the observation of these ties, these cords of sympathy which unite the body in its natural and healthful motions, in its agency under passion, and when suffering from disease, which the author proposes to be the chief subject of the following Essays. No one will deny that the signs in the eye must be noticed with more interest, and consequently with more minuteness, in proportion as the classification of its muscles and the sources of its sympathies are better understood.

It is repeatedly shown in these Essays, that the marks of passion and of bodily suffering are the same, and that the respiratory organs are the source of all expression, as well as of a very extensive range of symptoms in disease. Let us take an example of a mortal affection, to which my attention was first drawn by the study of expression.

When a soldier is desperately wounded by gunshot, or when amputation, or any other great operation of surgery is performed, a class of obscure symptoms sometimes arise, and the man dies, without the proximate cause of his death being comprehended. The cause of his death is inflammation in the lungs, but with symptoms so slight as to have no correspondence with the common description of pulmonary inflammation. There is no violent pain, no cough, no inflammatory pulse; you observe only a tremulous motion and swelling of the upper lip, and working of the muscles of the nostrils. Called to him by this sign, you find his voice feeble and his words cut; and with symptoms no more marked than these, he dies.

When we learn that the muscles about the lips and nostrils are respiratory muscles, and when we know that a respiratory nerve goes purposely to combine these muscles with the motion of the thorax, and above all, when by such investigation of the anatomy, we find that these same motions indicate some powerful emotions of the mind, are we not prepared to be more attentive observers, and to discover such symptoms as must remain obscure to those who have no clew to them ?

Perhaps it may be proper to make some apology for the sketches which accompany the text. I have often found it necessary to take the aid of the pencil, in slight marginal illustrations, in order to express what I despaired of making intelligible by the use of language merely; as in speaking of the forms of the head, or'the operation of the muscles of the face. The slightness of these sketches, as they appeared in the manuscript, explained sufficiently the humble intentions of the Author. But, under the graver, they have assumed an appearance more soft and finished, than was perhaps to be desired ; and certainly stand more in need of an apology for their incorrectness.

It was intended to place a sketch of hydrophobia on page 108, forgetting that the plate belonged to the subject treated of in page 126. It was necessary to fill the marginal space with another illustration of the subject, after the work was printed.

p 120

|

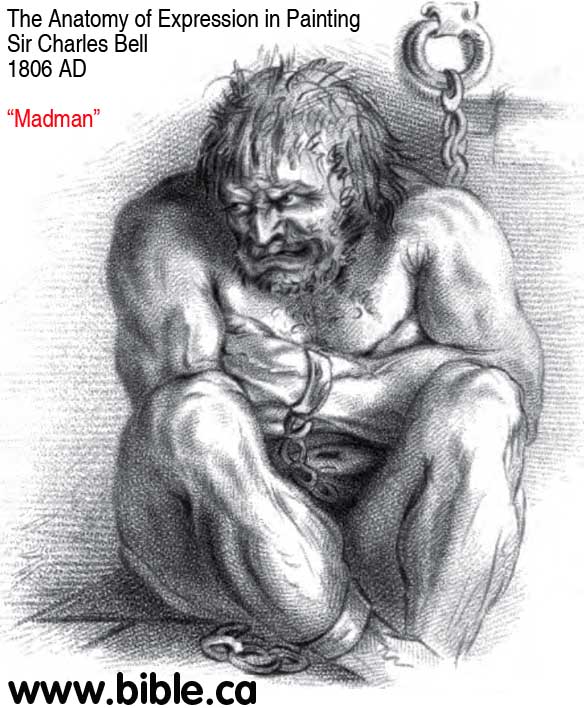

If I were to set down what ought to be represented as the prevailing character and physiognomy of a madman, I should say, that his body should be strong, and his muscles rigid and distinct; his skin bound; his features sharp; his eye sunk; his colour a dark brownish yellow, tinctured with sallowness, without one spot of enlivening carnation; his hair sooty black, stiff, and bushy. Or perhaps he might be represented as of a pale sickly yellow, with wiry red hair. "His burning eye, whom bloody streaks did stain, |

I do not mean here to trace the progress of the diseases of the mind, but merely to throw out some hints respecting the character of the outrageous maniac

.You see him lying in his cell regardless of every thing, with a death-like fixed gloom upon his countenance. When I say it is a death-like gloom, I mean a heaviness of the features without knitting of the brows or action of the muscles.

If you watch him in his paroxysm you may see the blood working to his head; his face acquires a darker red; he becomes restless; then rising from his couch he paces his cell and tugs his chains. Now his inflamed eye is fixed upon you, and his features lighten up into an inexpressible wildness and ferocity.

The error into which a painter would naturally fall, is to represent this expression by the swelling features of passion and the frowning eyebrow; but this would only convey the idea of passion, not of madness. Or he mistakes melancholia for madness. The theory upon which we are to proceed in attempting to convey this peculiar expression of ferocity amidst the utter wreck of the intellect, I conceive to be this, that the expression of mental energy should be avoided, and consequently all exertion of those muscles which are peculiarly indicative of sentiment. I conceive this to be consistent with nature, because I have observed (contrary to my expectation) that there was not that energy, that knitting of the brows, that indignant brooding and thoughtfulness in the face of madmen which is generally imagined to characterise their expression, and which we almost uniformly find given to them in painting. There is a vacancy in their laugh, and a want of meaning in their ferociousness.

To learn the character of the human countenance when devoid of expression, and reduced to the state of brutality, we must have recourse to the lower animals; and as I have already hinted, study their expression, their timidity, their watchfulness, their state of excitement, and their ferociousness. If we should transfer their expression to the human countenance, we should, as I conceive it, irresistibly convey the idea of madness, vacancy of mind, and mere animal passion.

But these discussions are only for the studies of the painter. The subject should be full in his mind, without its being for a moment imagined that such humiliating or disgusting details are suited to the canvas. If he has to represent madness, it is with a moral to show the consequences of vice and the indulgence of passion.

There are, however, subjects allied to this, which belong both to sacred and to classical painting—" And when the unclean spirit had torn him, and cried with a loud voice, he came out of him"— " And when the devil had thrown him in the midst, he came out of him."—By what aids is the painter to represent this demoniac phrensy; is it by the mere violence and extravagance of convulsion, or shall it be a creation from a mind learned as well as inventive ?

There is a link of connexion betwixt all liberal professions. The painter should sometimes borrow from the physician. If he has to represent a priestess or sibyl, he will require something more than his imagination can supply; he will readily conceive that the figure is full of energy, the imagination at the moment exalted and pregnant, and the expression bold and poetical—so that things long past are painted in colours as if they stood before her. But he will have a more precise and true idea of what is to be depicted, if he reads the history of that melancholia which undoubtedly in early times has given the idea of one possessed with a spirit. A young woman is constitutionally pale and languid, and from this inanimate state, no show of affection or entreaty will draw her into conversation with her family. But how changed is her condition when the blood mounts into her cheeks, and the eyes are dry and sparkling, the whole figure animated, and the voice possessed of new force, and with a tone so greatly altered that even a parent declares she does not know her child. How natural is then the belief that a spirit has entered into the inanimate body, and that this force of imagination and of language is not hers. The transition is easy; the priests assume the care of her, watch her ravings and give them meaning, until she is exhausted and sinks again into a death-like stupor or indifference.

Successive attacks of this kind indelibly impress the countenance. The painter has to represent features powerful, but consistent with the maturity and perfection of feminine beauty. His genius will be evinced, in his bestowing upon the countenance that deep tone of interest which belongs to features inactive but not lost to feeling. In the dead and uniform paleness of the face he ' will show something of that imprint of deep and long suffering without human sympathy—throw around her the appropriate mantle—let the fine hair descend on her shoulders—and the picture will not require golden letters to announce her character, as we see in old paintings of the Sibyl. p 120

By Steve Rudd:

Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.Send us your story about your experience with modern Psychiatry